This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Susan+49 (talk | contribs) at 04:34, 18 May 2011 (→References: Additional reference). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 04:34, 18 May 2011 by Susan+49 (talk | contribs) (→References: Additional reference)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

A paddle steamer is a steamship or boat, powered by a steam engine, using paddle wheels to propel it through the water. In antiquity, Paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses were wheelers driven by animals or humans. Modern paddle wheelers may be powered by diesel engines. Save for tourism and small pleasure boats (paddle boats) paddle propulsion is largely superseded by the screw propeller and other marine propulsion that have a higher efficiency, especially in rough or open water.

Paddle wheels

The paddle wheel is a large wheel, built on a steel framework, upon the outer edge of which are fitted numerous paddle blades (called floats or buckets). The bottom quarter or so of the wheel travels underwater. Rotation of the paddle wheel produces thrust, forward or backward as required. More advanced paddle wheel designs have featured feathering methods that keep each paddle blade oriented closer to vertical while it is in the water; this increases efficiency. The upper part of a paddle wheel is normally enclosed in a paddlebox to minimise splashing.

Types of paddle steamer

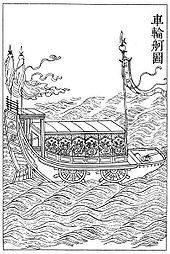

Right: detail of a steamer.

There are two basic ways to mount paddle wheels on a ship; either a single wheel on the rear, known as a stern-wheeler, or a paddle wheel on each side, known as a side-wheeler.

Stern-wheelers have generally been used as riverboats in the United States where they still operate for tourists on the Mississippi River.

Side-wheelers are used as riverboats and as coastal craft. While wider than a stern-wheeler, due to the extra width of the paddle wheels and their enclosing sponsons, a side-wheeler has extra manoeuvrability since they are usually rigged so the paddles can move at different rates, and even in differing directions (one forward, one reversed giving rapid turning capabilities). Due to this extra manoeuvrability side-wheelers were more popular on the narrower, windy rivers of the Murray-Darling system in Australia where a number are still in operation today.

European side-wheelers such as the PS Waverley have solid drive shafts that require both wheels to turn ahead or astern together, which limits manoeuvrability and gives a wide turning circle. Some were built with paddle clutches to disengage one or both paddles and allow them to turn independently. However early experience with side-wheelers requires them to be operated with clutches out, or as solid shaft vessels. It was noticeable that as ships approached their piers for docking, passengers would move to the side of the ship ready to disembark. The shift in weight when added to independent movements of the paddles could lead to imbalance and potential for capsize.

Paddle tugs were frequently operated with clutches in, as the lack of passengers aboard meant that independent paddle movement could be used safely and the added manoeuvrability exploited to the full.

Western world

The use of a paddle wheel in navigation appears for the first time in the mechanical treatise of the Roman engineer Vitruvius (De architectura, X 9.5-7), where he describes multi-geared paddle wheels working as a ship odometer. The first mention of paddle wheels as a means of propulsion comes from the 4th–5th century military treatise De Rebus Bellicis (chapter XVII), where the anonymous Roman author describes an ox-driven paddle-wheel warship:

Animal power, directed by the resources on ingenuity, drives with ease and swiftness, wherever utility summons it, a warship suitable for naval combats, which, because of its enormous size, human frailty as it were prevented from being operated by the hands of men. In its hull, or hollow interior, oxen, yoked in pairs to capstans, turns wheels attached to the sides of the ship; paddles, projecting above the circumference or curved surface of the wheels, beating the water with their strokes like oar-blades as the wheels revolve, work with an amazing and ingenious effect, their action producing rapid motion. This warship, moreover, because of its own bulk and because of the machinery working inside it, joins battle with such pounding force that it easily wrecks and destroys all enemy warships coming at close quarters.

The Italian physician Guido da Vigevano (c. 1280−1349), planning for a new crusade, made illustrations for a paddle boat that was propelled by manually turned compound cranks.

One of the drawings of the Anonymous Author of the Hussite Wars shows a boat with a pair of paddle-wheels at each end turned by men operating compound cranks (see above). The concept was improved by the Italian Roberto Valturio in 1463, who devised a boat with five sets, where the parallel cranks are all joined to a single power source by one connecting-rod, an idea adopted by his compatriot Francesco di Giorgio.

In 1543 the Spanish engineer Blasco de Garay in Barcelona made an experimental vessel propelled by a paddle-wheel on each side, worked by forty men. In the same year he showed Carlos I of Spain (also known as Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor), a new idea - a ship propelled by a giant wheel powered by steam. Carlos was not interested.

In 1787 Patrick Miller of Dalswinton invented a double-hulled boat, which was propelled on the Firth of Forth by men working a capstan which drove paddles on each side.

The first paddle steamer was the Pyroscaphe built by Marquis Claude de Jouffroy of Lyon in France, in 1783. It had a horizontal double-acting steam engine driving two 13.1-ft (4 m) paddle wheels on the sides of the craft. On July 15, 1783 it steamed up the Saône for fifteen minutes before the engine failed. Political events interrupted further development.

The next successful attempt at a paddle-driven steam ship was by the Scottish engineer William Symington who suggested steam power to Patrick Miller of Dalswinton. Experimental boats built in 1788 and 1789 worked successfully on Lochmaben Loch. In 1802, Symington built a barge-hauler, Charlotte Dundas, for the Forth and Clyde Canal Company. It successfully hauled two 70-ton barges almost 20 miles (30 km) in 6 hours against a strong headwind on test in 1802. There was much enthusiasm, but some directors of the company were concerned about the banks of the canal being damaged by the wash from a powered vessel, and no more were ordered.

While Charlotte Dundas was the first commercial paddle-steamer and steamboat, the first commercial success was possibly Robert Fulton's Clermont in New York, which went into commercial service in 1807 between New York City and Albany. Many other paddle-equipped river boats followed all around the world.

East Asia

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The first mention of a paddle-wheel ship from China is described in the History of the Southern Dynasties, compiled in the 7th century but describing the naval ships of the Liu Song Dynasty (420–479) used by admiral Wang Zhene in his campaign against the Qiang people in 418 AD. The mathematician and astronomer Zu Chongzhi (429–500) had a paddle-wheel ship built on the Xinting River (south of Nanjing) known as the "thousand league boat". When campaigning against Hou Jing in 552, the Liang Dynasty (502–557) admiral Xu Shipu employed paddle-wheel boats called "water-wheel boats". At the siege of Liyang in 573, the admiral Huang Faqiu employed foot-treadle powered paddle-wheel boats. A successful paddle-wheel warship design was made in China by Prince Li Gao in 784 AD, during an imperial examination of the provinces by the Tang Dynasty (618–907) emperor. The Chinese Song Dynasty (960–1279) issued the construction of many paddle-wheel ships for its standing navy, and according to historian Joseph Needham:

"...between 1132 and 1183 (AD) a great number of treadmill-operated paddle-wheel craft, large and small, were built, including stern-wheelers and ships with as many as 11 paddle-wheels a side,”.

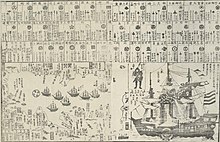

It is asserted that the standard Chinese term "wheel ship" was used by the Song period, whereas a litany of colorful terms were used to describe it beforehand. In the 12th century, the Song government used paddle-wheel ships en masse to defeat opposing armies of pirates armed with their own paddle-wheel ships. At the Battle of Caishi in 1161, paddle-wheelers were also used with great success against the Jin Dynasty (1115–1234) navy. The Chinese used the paddle-wheel ship even during the First Opium War (1839–1842) and for transport around the Pearl River during the early 20th century.

Seagoing paddle steamers

The first seagoing trip of a paddle steamer was that in 1808 of the Albany', which steamed from the Hudson River along the coast to the Delaware River. This was purely for the purpose of moving a river-boat to a new market, but the use of paddle-steamers for short coastal trips began soon after that.

The first paddle-steamer to make a long ocean voyage was SS Savannah, built in 1819 expressly for this service. Savannah set out for Liverpool on May 22, 1819, sighting Ireland after 23 days at sea. This was the first powered crossing of the Atlantic, although Savannah also carried a full rig of sail to assist the engines when winds were favorable. In 1822, Charles Napier's Aaron Manby, the world's first iron ship, made the first direct steam crossing from London to Paris and the first seagoing voyage by an iron ship.

In 1838, Sirius, a fairly small steam packet built for the Cork to London route, became the first vessel to cross the Atlantic under sustained steam power, beating Isambard Kingdom Brunel's much larger Great Western by a day. Great Western, however, was actually built for the transatlantic trade, and so had sufficient coal for the passage; Sirius had to burn furniture and other items after running out of coal. The Great Western’s more successful crossing began the regular sailing of powered vessels across the Atlantic. Beaver was the first coastal steamship to operate in the Pacific Northwest of North America. Paddle steamers helped open Japan to the Western World in the mid-19th century.

The largest paddle-steamer ever built was Brunel's Great Eastern, but it also had screw propulsion and sail rigging. It was 692 ft (211 m) long and weighed 32,000 tons, its paddle-wheels being 56 ft (17 m) in diameter.

In oceangoing service, paddle steamers became much less useful after the invention of the screw propeller, but they remained in use in coastal service and as river tugboats, thanks to their shallow draught and good maneuverability.

See also: Paddle frigateModern paddle steamers

A few paddle steamers serve niche tourism needs as cruise boats on lakes and others, such as the Delta Queen, still operate on the Mississippi River and in the Pacific Northwest along the Willamette River, as do a few in the United Kingdom and elsewhere in Europe.

PS Skibladner is the oldest steamship in regular operation. Built in 1856, she still operates on lake Mjøsa in Norway.

PS Washington Irving, built in 1912 by the New York Shipbuilding Company, was the biggest passenger-carrying riverboat ever built with a capacity for 6,000 passengers. It was operated on the Hudson River from 1913 until it was sunk in an accident in 1926. One of the last paddle steamers built in the U.S. was the dredge Error: {{Ship}} missing prefix (help), built in 1934 and now a National Historic Landmark.

PS Waverley, built in 1947, is the last seagoing paddle steamer in the world. This ship sails a full season of cruises from ports around Britain, and sailed across the English Channel to commemorate the sinking of her predecessor of 1899 at the 1940 Battle of Dunkirk.

PS Adelaide is the oldest wooden-hulled paddle steamer in the world. Built in 1866, she operates from the Port of Echuca, on Australia's Murray River, which has the largest fleet of paddle steamers in the world. The replica paddle steamer Curlip was constructed in Gippsland, Australia, and launched in November 2008.

Also in Australia, the PS Kookaburra Queen services the Brisbane River, operating as a floating restaurant or venue for hire.

The PS Enterprise, built in Echuca in 1876-78 and now berthed at a wharf on the Acton Peninsula, Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra, has been restored to full working order. PS Enterprise was used on the Murray River, the Darling River and the Murrumbidgee River in New South Wales between 1978 and 1988, when it was recommissioned after restoration.

The Elbe river Saxon Paddle Steamer Fleet in Dresden (known as "White Fleet"), Germany, is the oldest and biggest in the world, with around 700,000 passengers per year. The 1913-built Goethe was the last paddle steamer on the River Rhine. Previously the world's largest sidewheeler with a two-cylinder steam engine of 700 hp (520 kW), a length of 83 m and a height above water of 9.2 m, the Goethe was converted to Diesel-Hydraulic power during the winter of 2008/09.

Switzerland has a large paddle steamer fleet, most of the "Salon Steamer-type" built by Sulzer in Winterthur or Escher-Wyss in Zurich. There are five active and one inactive on Lake Lucerne, two on Lake Zurich, and one each on Lake Brienz, Lake Thun and Lake Constance. Swiss company CGN operates a number of paddle steamers on Lake Geneva. Their fleet includes three converted to diesel electric power in the 1960s and five retaining steam. One, Montreux, was reconverted in 2000 from diesel to an all-new steam engine. It is the world's first electronically remote-controlled steam engine and has operating costs similar to state-of-the-art diesels, while producing up to 90 percent less air pollution.

In the USSR, river paddle steamers of the type Iosif Stalin (project 373), later renamed Ryazan-class steamships, were built until 1951. Between 1952 and 1959, ships of this type were built for the Soviet Union by Obuda Hajogyar Budapest factory in Hungary. In total, 75 type Iosif Stalin/Ryazan side-wheelers were built. They are 70 m long and can carry up to 360 passengers. Few of them still remain in active service.

In Italy, a small paddle steamer fleet operates on Lake Como and Lake Garda, primarily for tourists.

On the Isle of Wight, PS Monarch (one of the smallest passenger-carrying vessels of her type) takes trips on the River Medina. Monarch is a side wheeler built at Chatham Historic Dockyard in Kent.

The restored paddle steamer Waimarie is based in Wanganui, New Zealand. The Waimarie was built in kitset form in Poplar, London in 1899, and originally operated on the Whanganui River under the name Aotea. Later renamed, she remained in service until 1949. She sank at her moorings in 1952, and remained in the mud until raised by volunteers and restored to begin operations again in 2000.

Paddle tugs

The British Admiralty used diesel-electric paddle tugs in recent times. Each paddle wheel was driven by an individual electric motor, giving outstanding maneuverability. Paddle tugs were able to more easily make use of the inherent advantage of side wheel paddle propulsion, having the option to disconnect the clutches that connected the paddle drive shafts as one. This enabled them to turn one paddle ahead and one astern to turn and manuvre quickly.

See also

References

- Hall, Bert S. (1979), The Technological Illustrations of the So-Called "Anonymous of the Hussite Wars". Codex Latinus Monacensis 197, Part 1, Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, ISBN 3-920153-93-6

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Part 7, Military Technology; The Gunpowder Epic. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Clark, John and Wardle, David (2003). PS Enterprise. Canberra: National Museum of Australia.

- University of Wisconsin–La Crosse Historic Steamboat Photographs

- White, Jr., Lynn (1962), Medieval Technology and Social Change, Oxford: At the Clarendon Press

- Dumpleton, Bernard, "The Story of the Paddle Steamer", Melksham, 2002.

Notes

- Experience of economics: The paddle designs using diesels are tourist vessels servicing sightseeing attractions or replica riverboats and are mainly restaurants and casinos.

- As a sampling: Steamers operate on Lake Champlain, Lake George, and Lake Winnipesaukee in the U.S. Northeast as of 2024.

Footnotes

- De Rebus Bellicis (anon.), chapter XVII, text edited by Robert Ireland, in: BAR International Series 63, part 2, p. 34

- Hall 1979, p. 80

- ^ White, Jr. 1962, p. 114

- H.P.Spratt, "The Birth of the Steamboat",(London, 1958)

- Kurlansky, Mark. 1999. The Basque History of the World. Walker & Company, New York. ISBN 0-8027-1349-1, p. 56

- Dayton, Fred Erving (1925), "Two Thousand Years of Steam", Steamboat Days, Frederick A. Stokes company, p. 1

- ^ Smiles, Samuel (1884), Men of Invention and Industry, Gutenberg e-text

{{citation}}: External link in|publisher= - Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 31.

- Needham, 476

- Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 165–166.

- Men of Iron : Brunel, Stephenson and the Inventions That Shaped the Modern World by Sally Dugan ISBN 978-1405034265

- Str. Portland

- Oregon Maritime Museum

- Sächsische Dampfschiffahrt

- RMS Goethe KD - Köln-Düsseldorfer Rheinschiffahrt

- German Misplaced Pages on the ship Goethe

- Russian river ships (in English)

- Russian passenger river fleet (in Russian)

- Whanganui River Boat Centre

External links

- links to videos on paddle wheelers

- links to photos of a modern design on paddle wheelers

- PS Enterprise A restored 19th century paddle boat at the National Museum of Australia

- Australian paddle steamers A brief history.