This is an old revision of this page, as edited by E Pluribus Anthony (talk | contribs) at 21:47, 10 March 2006 (cpyed: noun). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:47, 10 March 2006 by E Pluribus Anthony (talk | contribs) (cpyed: noun)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Bilateral relations | |

United States |

Israel |

|---|---|

Israel-United States relations have evolved from an initial United States policy of sympathy and support for the creation of a Jewish homeland in 1948 to an unusual partnership that links a small but militarily powerful Israel, dependent on the United States for its economic and military strength, with the U.S. superpower trying to balance competing interests in the region. Some in the United States question the levels of aid and general commitment to Israel, and argue that a U.S. bias toward Israel operates at the expense of improved U.S. relations with various Arab states. Others maintain that democratic Israel is a strategic ally, and that U.S. relations with Israel strengthens the U.S. presence in the Middle East.

Recognition and Early Relationship

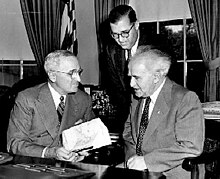

On May 14, 1948, the United States, under President Truman, became the first country to extend de facto recognition to the State of Israel. Past American presidents, encouraged by active support from civic groups, labor unions, political parties, and members of the American and world Jewish communities, supported the concept, articulated in Britain's 1917 Balfour Declaration, of a Jewish homeland.

The decision was still contentious, however, with significant disagreement between Truman and the State Department about how to handle the situation. Truman was a supporter of the Zionist movement, while Secretary of State George Marshall feared U.S. backing of a Jewish state would harm relations with the Muslim world, limit access to Middle Eastern oil, and destabilize the region. On May 12, 1948, in the Oval Office, Marshall told Truman he would vote against him in the next election if the U.S. recognized Israel.1 In the end, Truman, recognized the state of Israel 11 minutes after it declared itself a nation. De jure recognition came on January 31, 1949.

Under vastly different geopolitical circumstances, U.S. policy was geared toward supporting the development of oil-producing countries, maintaining a neutral stance in the Arab-Israeli conflict, and preventing Soviet influence from gaining a foothold in Iran and Turkey. U.S. policymakers used foreign aid in the 1950s and 1960s to support these objectives.

U.S. aid to Israel was far less in the 1950s and 1960s than in later years. Although the United States provided moderate amounts of economic aid (mostly loans) to Israel, at the time, Israel's main patron was France, which supported Israel by providing it with advanced military equipment and technology. This support was to counter the perceived threat from Egypt under President Gamal Abdel Nasser regarding the Suez Canal.

During the 1956 Suez Crisis, the U.S., fearing a Soviet intervention on behalf of Egypt, forced a cease-fire on Britain, France, and Israel. The Suez Crisis was the last occasion on which the United States placed strong forceful public pressure on Israel. Afterwards, particularly during the presidency of Lyndon Johnson, it demonstrated a whole-hearted (but by no means unquestioning) support for Israel. The U.S. took some care to avoid giving the appearance of any active military alliance in the period before the 6-Day War of 1967.

In 1962, Israel purchased its first advanced weapons system from the United States, Hawk antiaircraft missiles. In 1968, a year after Israel's victory in the Six Day War, the Johnson Administration, with strong support from Congress, approved the sale of Phantom fighters to Israel, establishing the precedent for U.S. support for Israel's qualitative military edge over its neighbors.

Carter Administration (1977-1981)

The Carter years were characterized by very active U. S. involvement in the Middle East peace process, and, as a consequence, led to some friction in U. S.-Israeli bilateral relations. The Carter-initiated Camp David process was viewed by some in Israel as creating U.S. pressures on Israel to withdraw from occupied territories and to take risks for the sake of peace with Egypt. President Carter's support for a Palestinian "homeland" and for Palestinian political rights created additional tensions with Israel. Some argue that the final text of the Camp David accords represented Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin's success in limiting Israeli requirements to deal with the Palestinians.

Reagan Administration (1981-1989)

Israeli supporters expressed concerns early in the first Reagan term about potential difficulties in U. S.-Israeli relations, in part because several Presidential appointees had ties or past business associations with key Arab countries (Secretaries Weinberger and Shultz, for example, were officers in the Bechtel Corporation, which has strong links to the Arab world.) But President Reagan's personal support for Israel and the compatibility between Israeli and Reagan perspectives on terrorism, security cooperation, and the Soviet threat, led to dramatic improvements in bilateral relations.

In 1981, Weinberger and Israeli Minister of Defense Ariel Sharon signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU), establishing a framework for continued consultation and cooperation to enhance the national security of both countries. In November 1983, the two sides formed a Joint Political Military Group, which meets twice a year, to implement most provisions of the MOU. Joint air and sea military exercises began in June of 1984, and the United States has constructed facilities to stockpile military equipment in Israel. Although the Lebanon war of 1982 exposed some serious differences between Israeli and U.S. policies, such as Israel's use of U.S.-provided military equipment in the attack on Lebanon and Israel's rejection of the Reagan peace plan of September 1, 1982, it did not alter the Administration's favoritism for Israel and the emphasis it placed on Israel's importance to the United States.

U.S.-Israeli ties strengthened during the second Reagan term. Israel was granted "major non-NATO ally" status in 1988 that gave it access to expanded weapons systems and opportunities to bid on U.S. defense contracts. The United States maintained grant aid to Israel at $3 billion annually and implemented a free trade agreement in 1985. Since then all customs duties between the two trading partners have since been eliminated.

In November 1985, Jonathan Pollard, a civilian U.S. naval intelligence employee, and his wife were charged with selling classified documents to Israel. Four Israeli officials also were indicted. The Israeli government claimed that it was a rogue operation. Pollard was sentenced to life in prison and his wife to two consecutive five-year terms. Israelis complain that Pollard received an excessively harsh sentence, and some Israelis have made a cause of his plight. Pollard was granted Israeli citizenship in 1996, and Israeli officials periodically raise the Pollard case with U.S. counterparts, although there is not a formal request for clemency pending.

The second Reagan term ended on what many Israelis considered to be a sour note when the United States opened a dialog with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in December 1988. But, despite the U.S.-PLO dialog, the Pollard spy case, or the Israeli rejection of the Shultz peace initiative in the spring of 1988, pro-Israeli organizations in the United States characterized the Reagan Administration (and the 100th Congress) as the "most pro-Israel ever" and praised the positive overall tone of bilateral relations.

Bush Administration (1989-1993)

Secretary of State James Baker told an American-Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC, the pro-Israel lobby) audience on May 22, 1989, that Israel should abandon its expansionist policies, a remark many took as a signal that the pro-Israel Reagan years were over. President Bush raised Israeli ire when he reminded a press conference on March 3, 1990, that East Jerusalem was occupied territory and not a sovereign part of Israel as the Israelis claimed. The United States and Israel disagreed over the Israeli interpretation of the Israeli plan to hold elections for a Palestinian peace conference delegation in the summer of 1989, and also disagreed over the need for an investigation of the Jerusalem incident of October 8, 1990, in which Israeli police killed 17 Palestinians.

Amid Iraqi threats against Israel generated by the Iraq-Kuwait crisis, former President Bush repeated the U.S. commitment to Israel's security. Israeli-U.S. tension eased after the start of the Persian Gulf war on January 16, 1991, when Israel became a target of Iraqi Scud missiles. The United States urged Israel not to retaliate against Iraq for the attacks because it was believed that Iraq wanted to draw Israel into the conflict and force other coalition members, Egypt and Syria in particular, to quit the coalition and join Iraq in a war against Israel. Israel did not retaliate, and gained praise for its restraint.

Bush and Baker were instrumental in convening the Madrid peace conference in October 1991 and in persuading all the parties to engage in the subsequent peace negotiations. It was reported widely that the Bush Administration did not share an amicable relationship with the Shamir government. After the Labor party won the 1992 election, U.S.-Israel relations appeared to improve. The Labor coalition approved a partial housing construction freeze in the occupied territories on July 19, something the Shamir government had not done despite Bush Administration appeals for a freeze as a condition for the loan guarantees.

Clinton Administration (1993-2000)

Israel and the PLO exchanged letters of mutual recognition on September 10, and signed the Declaration of Principles on September 13, 1993. President Clinton announced on September 10 that the United States and the PLO would reestablish their dialog. On October 26, 1994, President Clinton witnessed the Jordan-Israeli peace treaty signing, and President Clinton, Egyptian President Mubarak, and King Hussein of Jordan witnessed the White House signing of the September 28, 1995 Interim Agreement between Israel and the Palestinians.

President Clinton attended the funeral of assassinated Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in Jerusalem in November, 1995. Following a March, 1996 visit to Israel, President Clinton offered $100 million in aid for Israel's anti-terror activities, another $200 million for the Arrow anti-missile deployment, and about $50 million for an anti-missile laser weapon. President Clinton disagreed with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's policy of expanding Jewish settlements in the occupied territories, and it was reported that the President believed that the Prime Minister delayed the peace process. President Clinton hosted negotiations at the Wye River Conference Center in Maryland, ending with the signing of an agreement on October 23, 1998. Israel suspended implementation of the Wye agreement in early December 1998, because Prime Minister Netanyahu said the Palestinians violated the Wye Agreement by threatening to declare a state (Palestinian statehood was not mentioned in Wye). In January 1999, the Wye Agreement was delayed until the Israeli elections in May. Ehud Barak was elected Prime Minister on May 17, 1999, and won a vote of confidence for his government on July 6, 1999. President Clinton and Prime Minister Barak appeared to establish close personal relations during four days of meetings between July 15 and 20 in what many observers believed was a clear reversal of the less than friendly relations between Clinton and Netanyahu. President Clinton mediated meetings between Prime Minister Barak and Chairman Arafat at the White House, Oslo, Shepherdstown, Camp David, and Sharm al-Shaykh in the search for peace.

Bush Administration (2001 -)

President George W. Bush and Prime Minister Sharon established good relations in their March and June 2001 meetings. On October 4, 2001, Sharon accused the Bush Administration of appeasing the Palestinians at Israel's expense in a bid for Arab support for the U. S. anti-terror campaign. The White House said the remark was unacceptable. Rather than apologize for the remark, Sharon said the United States failed to understand him. Also, the United States criticized the Israeli practice of assassinating Palestinians believed to be engaged in terrorism, which appeared to some Israelis to be inconsistent with the U.S. policy of pursuing international terrorist Osama bin Laden "dead or alive."

All recent U.S. Administrations have disapproved of Israel's settlement activity as prejudging final status and possibly preventing the emergence of a contiguous Palestinian state. President Bush, however noted the need to take into account changed "realities on the ground, including already existing major Israeli population center," (i.e., settlements), asserting "it is unrealistic to expect that the outcome of final status negotiations will be full and complete return to the armistice lines of 1949." He later emphasized that it was a subject for negotiations between the parties.

At times of violence, U.S. officials have urged Israel not use disproportionate force and to withdraw as rapidly as possible from Palestinian areas retaken in security operations. The current Bush Administration has insisted that U.N. Security Council resolutions be "balanced," by criticizing Palestinian as well as Israeli violence and has vetoed resolutions which do not meet that standard.

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice has not named a Special Middle East Envoy and has said that she will not get involved in direct Israeli-Palestinian negotiations of issues. She says prefers to have the Israelis and Palestinians work together, although she has traveled to the region several times in 2005. The Administration supported Israel's disengagement from Gaza as a way to return to the Road Map process to achieve a solution based on two states, Israel and Palestine, living side by side in peace and security. The evacuation of settlers from the Gaza Strip and four small settlements in the northern West Bank was completed on August 23, 2005.

Current Issues

Aid: Israel has been the largest recipient of U.S. foreign aid since 1976. In 1998, Israeli, congressional, and Administration officials agreed to reduce U.S. $1.2 billion in Economic Support Funds (ESF) to zero over ten years, while increasing Foreign Military Financing (FMF) from $1.8 billion to $2.4 billion. Separately from the scheduled cuts, however, Israeli has received an extra $1.2 billion to fund implementation of the Wye agreement, $200 million in anti-terror assistance in, and $1 billion in FMF in the supplemental appropriations bill for fiscal year 2003. For the 2005 fiscal year, Israel received $357 million in ESF, $2.202 billion in FMF, and $50 million in migration settlement assistance. For 2006, the Administration has requested $240 million in ESF and $2.28 billion in FMF. H.R. 3057, passed in the House on June 28, 2005, and in the Senate on July 20, approves these amounts. House and Senate measures also support $40 million for the settlement of migrants from the former Soviet Union and take note of Israel's plan to bring remaining Ethiopian Jews to Israel in three years.

Israeli press reported that Israel is requesting about $2.25 billion in special aid in a mix of grants and loan guarantees over four years, with one-third to be used to relocate military bases from the Gaza Strip to Israel in the disengagement from Gaza and the rest to develop the Negev and Galilee regions of Israel and for other purposes, but none to help compensate settlers or for other civilian aspects of the disengagement. An Israeli team has visited Washington to present elements of the request, and preliminary discussions are underway. No formal request has been presented to Congress. In light of the costs inflicted on the United States by Hurricane Katrina, an Israeli delegation intending to discuss the aid canceled a trip to Washington.

Congress has legislated other special provisions regarding aid to Israel. Since the 1980s, ESF and FMF have been provided as all grant cash transfers, not designated for particular projects, transferred as a lump sum in the first month of the fiscal year, instead of in periodic increments. Israel is allowed to spend about one-quarter of the military aid for the procurement in Israel of defense articles and services, including research and development, rather than in the United States. Finally, to help Israel out of its economic slump, the U.S. provided $9 billion in loan guarantees over three years, use of which has since been extended to 2008. As of July 2005, Israel had not used $4.9 billion of the guarantees.

Military Sales: Over the years, the United States and Israel have regularly discussed Israel's sale of sensitive security equipment and technology to various countries, especially China. Israel reportedly is China's second major arms supplier, after Russia. Israel is ranked fourth among the world's arms suppliers. U.S. administrations believe that such sales are potentially harmful to the security of U.S. forces in Asia.

In 2000, the United States persuaded Israel to cancel the sale of the Phalcon, an advanced, airborne early-warning system, to China. In 2005, the U.S. Department of Defense was angered by Israel's agreement to upgrade Harpy Killer unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) that it sold to China in 1999. China tested the weapon over the Taiwan Strait in 2004. The Department suspended technological cooperation with the Israel Air Force on the future F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) aircraft as well as several other cooperative programs, held up shipments of some military equipment, and refused to communicate with Israeli Defense Ministry Director General Amos Yaron, whom Pentagon officials believe misled them about the Harpy deal. According to a reputable Israeli military journalist, the U.S. Department of Defense demanded details of 60 Israeli deals Israeli with China, an examination of Israel's security equipment supervision system, and a memorandum of understanding about arms sales to prevent future difficulties.

On October 21, 2005, it was reported that Israel will freeze or cancel a deal to provide maintenance for 22 Venezuelan Air Force F-16 fighter jets. The Israeli government had requested U.S. permission to proceed with the deal, but permission has not been granted.

Jerusalem: Since taking East Jerusalem in the 1967 war, Israel has insisted that Jerusalem is its indivisible, eternal capital. Few countries have agreed with this position. The U.N.'s 1947 partition plan called for the internationalization of Jerusalem, while the Declaration of Principles signed by Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization in September 1993 says that it is a subject for permanent status negotiations. U.S. Administrations have recognized that Jerusalem's status is unresolved by keeping the U.S. Embassy in Tel Aviv. However, in 1995, both houses of Congress mandated that the embassy be moved to Jerusalem, and only a series of presidential waivers of penalties for non-compliance have delayed that event. U.S. legislation has granted Jerusalem status as a capital in particular instances and sought to prevent U.S. official recognition of Palestinian claims to the city. The failure of the State Department to follow congressional guidance on Jerusalem has prompted a response in H.R. 2601, the Foreign Relations Authorization bill, passed in the House on July 20, 2005.

References

"Israeli-United States Relations" Almanac of Policy Issues

See also

External links

- Israeli Embassy in Washington,D.C. page on U.S.-Israel relations

- United States Embassy in Israel

- U.S. rejects Israeli request to join visa waiver plan by Aluf Benn, Haaretz, February 19, 2006