This is an old revision of this page, as edited by CheMoBot (talk | contribs) at 20:45, 7 August 2011 (Updating {{drugbox}} (no changed fields - added verified revid - updated 'DrugBank_Ref', 'ChEBI_Ref', 'KEGG_Ref', 'DrugBank_Ref') per Chem/Drugbox validation (report [[Misplaced Pages talk:WikiProject_). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:45, 7 August 2011 by CheMoBot (talk | contribs) (Updating {{drugbox}} (no changed fields - added verified revid - updated 'DrugBank_Ref', 'ChEBI_Ref', 'KEGG_Ref', 'DrugBank_Ref') per Chem/Drugbox validation (report [[Misplaced Pages talk:WikiProject_)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Pharmaceutical compound | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | (3β)-3-Hydroxyandrost-5-en-17-one |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 12 hours |

| Excretion | Urinary:?% |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.160 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

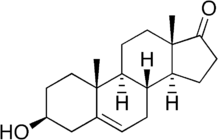

| Formula | C19H28O2 |

| Molar mass | 288.424 g/mol g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 148.5 °C (299.3 °F) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

5-Dehydroepiandrosterone (5-DHEA) is a 19-carbon endogenous natural steroid hormone. It is the major secretory steroidal product of the adrenal glands and is also produced by the gonads and the brain. DHEA is the most abundant circulating steroid in humans.

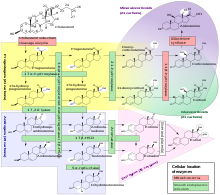

DHEA has been implicated in a broad range of biological effects in humans and other mammals. It acts on the androgen receptor both directly and through its metabolites, which include androstenediol and androstenedione, which can undergo further conversion to produce the androgen testosterone and the estrogens, including estrone, estradiol, and estriol. DHEA is also a potent sigma-1 agonist. It is considered a neurosteroid.

Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate

Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) is the sulfated version of DHEA. This conversion is reversibly catalyzed by sulfotransferase (SULT2A1) primarily in the adrenals, the liver, and small intestine. In the blood, most DHEA is found as DHEAS with levels that are about 300 times higher than those of free DHEA. Orally ingested DHEA is converted to its sulfate when passing through intestines and liver. Whereas DHEA levels naturally reach their peak in the early morning hours, DHEAS levels show no diurnal variation. From a practical point of view, measurement of DHEAS is preferable to DHEA, as levels are more stable.

Production

DHEA is produced from cholesterol through two cytochrome P450 enzymes. Cholesterol is converted to pregnenolone by the enzyme P450 scc (side chain cleavage); then another enzyme, CYP17A1, converts pregnenolone to 17α-Hydroxypregnenolone and then to DHEA.

Role

DHEA can be understood as a prohormone for the sex steroids. DHEAS may be viewed as buffer and reservoir. As most DHEA is produced by the zona reticularis of the adrenal cortex, it is argued that there is a role in the immune and stress response.

As almost all DHEA is derived from the adrenal glands, blood measurements of DHEAS/DHEA are useful to detect excess adrenal activity as seen in adrenal cancer or hyperplasia, including certain forms of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome tend to have elevated levels of DHEAS.

Effects and uses

Depression

DHEA is a cortisol antagonist. Research studies indicate that DHEA supplementation has an anti-depressant effect and protects from cortisol overconcentration over long time scales.

Memory

DHEA supplementation has been studied as a treatment for Alzheimer's disease, but was not found to be effective. Some small placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial studies have found long-term supplementation to improve mood and relieve depression found that a 7-day course of DHEA (150 mg twice daily) improved episodic memory in healthy young men. In this study, DHEA was also shown to improve subjective mood and decrease evening cortisol concentration, which is known to be elevated in depression. The effect of DHEA on memory appeared to be related to an early activation of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and it was suggested this was due to neuronal recruitment of the steroid sensitive ACC that may be involved in pre-hippocampal memory processing.

Consistent with this hypothesis are DHEA-S data from several studies of military special operations units. In these studies, warfighters who exhibited higher levels of DHEA and higher DHEA/cortisol ratios during extreme stress were those who also exhibited superior hippocampal and prefrontal dependent cognitive abilities during stress.

Physical performance

DHEA supplements are sometimes used as muscle-building or performance-enhancing drugs by athletes. However, a randomized placebo-controlled trial found that DHEA supplementation had no (statistically significant) effect on lean body mass, strength, or testosterone levels.

Infertility and Reproduction

Since 2000, DHEA supplementation has been used in reproductive medicine in combination with gonadotropins as a way to treat female infertility. The hormone is believed to act on the chromosomal integrity of eggs, creating healthier embryos and increasing the chances of a successful pregnancy. A study released in 2010 from Tel Aviv University showed that women who took DHEA supplements prior to an infertility treatment were three times more likely to conceive than those who did not. Additionally, studies conducted by the Center for Human Reproduction in New York found that women with poor ovarian reserve who were supplemented with DHEA 4 to 12 weeks prior to an IVF cycle had a 22% reduction in number of chromosomally abnormal embryos and a 50-80% reduction in miscarriages.

Cardiovascular disease and risk of death

A 1986 study found that a higher level of endogenous DHEA, as determined by a single measurement, correlated with a lower risk of death or cardiovascular disease. However, a more recent 2006 study found no correlation between DHEA levels and risk of cardiovascular disease or death in men. A 2007 study found the DHEA restored oxidative balance in diabetic patients, reducing tissue levels of pentosidine—a biomarker for advanced glycation endproducts.

Cancer

Some in vitro studies have found DHEA to have both anti-proliferative and yet also apoptotic effect on cancer cell lines. The clinical significance of these findings, if any, is unknown. Higher levels of DHEA and other endogenous sex hormones are strongly associated with an increased risk of developing breast cancer in both pre- and postmenopausal women.

Diabetes and carotid atherosclerosis

A 2005 study, measured serum DHEA in 206 men with type-2 diabetes, and found an inverse relationship between serum DHEA and carotid atherosclerosis in men. The authors say the study "supports the notion that DHEA, which is sold in increasing amount as a food supplement, is atheroprotective in humans, and that androgen replacement therapy should be considered for men with hypogonadism."

Men over 65

A 2006 study supplemented DHEA to men of average 65 years of age, and found that the men experienced significant increases in testosterone and cGMP (Cyclic guanosine monophosphate), and significant decreases in low-density lipoprotein (LDL). The authors say that the "findings...suggest that chronic DHEA supplementation would exert antiatherogenic effects, particularly in elderly subjects who display low circulating levels of this hormone."

Longevity

A 2008 study in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, June 2008, measured serum DHEA in 940 men and women ranging from age 21 to 88, following them from 1978 until 2005. The researches found that low levels of DHEA-s showed a significant association with shorter lifespan and that higher DHEA-s levels are a "strong predictor" of longevity in men, even after adjusting for age, blood pressure, and plasma glucose. No relationship was found between serum DHEA and longevity for women during the study period. The study did not find a significant difference in longevity until the 15-year follow-up point, which the researchers note may explain why some past research that followed men for less duration found no relationship.

"No reason to prescribe"

An anonymous 2002 review, in the French journal Prescrire, concluded: DHEA plasma levels are so low in most animals that they are difficult to measure, hindering studies on DHEA and aging. DHEA had not yet, at the time of writing, been linked to any specific health disorder. Side effects are linked to its androgenic effects, unfavorable lipid metabolism effects, and "possible growth-stimulating effect" on hormone dependent malignancies. "In practice, there is currently no scientific reason to prescribe DHEA for any purpose whatsoever."

Disputed effects

In the United States, DHEA or DHEAS have been advertised with claims that they may be beneficial for a wide variety of ailments. DHEA and DHEAS are readily available in the United States, where they are marketed as over-the-counter dietary supplements. A 2004 review in the American Journal of Sports Medicine concluded that "The marketing of this supplement's effectiveness far exceeds its science." Because DHEA must first be converted to androstenedione and then to testosterone in men, it has two chances to aromatize into estrogen - estrone from androstenedione, and estradiol from testosterone. As such, it is possible that supplementation with DHEA could increase estrogen levels more than testosterone levels in men.

Side effects

As a hormone precursor, there has been a smattering of reports of side effects possibly caused by the hormone metabolites of DHEA. Some of these include possibly serious cardiovascular effects such as heart palpitations.

Increasing endogenous production

Regular exercise is known to increase DHEA production in the body. Calorie restriction has also been shown to increase DHEA in primates. Some theorize that the increase in endogenous DHEA brought about by calorie restriction is partially responsible for the longer life expectancy known to be associated with calorie restriction.

Isomers

The term "dehydroepiandrosterone" is ambiguous chemically because it does not include the specific positions within epiandrosterone at which hydrogen atoms are missing. DHEA has a number of naturally occurring isomers that may have similar pharmacological effects. Some isomers of DHEA are 1-dehydroepiandrosterone (shown to be synthesized in pigs) and 4-dehydroepiandrosterone (shown to occur in rats). These isomers are also technically DHEA, since they are dehydroepiandrosterones in which hydrogens are removed from the epiandrosterone skeleton.

Legality

United States

A bill has been introduced, in March 2009, in the U.S. Senate (S. 641) that attempts to classify DHEA as a controlled substance under the category of anabolic steroids. The sponsor is Charles Grassley (R-IA). The cosponsors are Richard Durbin (D-IL), and John McCain (R-AZ). This bill was referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee. In December 2007, Charles Grassley introduced the "S. 2470: Dehydroepiandrosterone Abuse Reduction Act of 2007," in an attempt to amend the Controlled Substances Act to make "unlawful for any person to knowingly selling, causing another to sell, or conspiring to sell a product containing dehydroepiandrosterone to an individual under the age of 18 years, including any such sale using the Internet," without a prescription. Only civil (non-criminal) penalties are provided. The bill was read twice and referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee where it died.

Canada

In Canada, a prescription is required to buy DHEA.

Sports and athletics

DHEA is a prohibited substance under the World Anti-Doping Code of the World Anti-Doping Agency, which manages drug testing for Olympics and other sports. In January 2011, NBA player O.J. Mayo was given a 10-game suspension after testing positive for DHEA. Mayo termed his use of DHEA as "an honest mistake". Mayo is the seventh player to test positive for performance-enhancing drugs since the league began testing in 1999. Rashard Lewis, then with the Orlando Magic, tested positive for DHEA and was suspended 10 games before the start of the 2009-10 season.

Synonyms and brand names

Synonyms for dehydroepiandrosterone:

The International Nonproprietary Name name is prasterone. Systematic names include 3-beta-hydroxy-5-androsten-17-one, 3-beta-hydroxyandrost-5-en-17-one, 3beta-hydroxy-5-androsten-17-one, 3beta-hydroxy-androst-5-en-17-one, 3beta-hydroxy-D5-androsten-17-one, 3beta-hydroxyandrost-5-en-17-one, 3beta-hydroxyandrost-5-ene-17-one, 3-beta-hydroxy-etioallocholan-5-ene-17-one, 5-androsten-3beta-ol-17-one.

Fluasterone is a synthetic derivative of DHEA. Fidelin is a 3-part combination of DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone and prasterone; it was investigated by Paladin Labs Inc. of Canada circa 2003, but by 2010 Paladin had abandoned this project

References

- The NIH National Library of Medicine — Dehydroepiandrosterone http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/natural/patient-dhea.html

- The Merck Index, 13th Edition, 7798

-

Schulman, Robert A., M.D. (2007). Solve It With Supplements. New York City: Rodale, Inc. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-57954-942-8.

DHEA (Dehydroepiandrosterone) is a common hormone produced in the adrenal glands, the gonads, and the brain.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - William F Ganong MD, 'Review of Medical Physiology', 22nd Ed, McGraw Hill, 2005, page 362.

- ^ Mo Q, Lu SF, Simon NG (2006). "Dehydroepiandrosterone and its metabolites: differential effects on androgen receptor trafficking and transcriptional activity". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 99 (1): 50–8. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.11.011. PMID 16524719.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Romieu, P.; Martin-Fardon, R.; Bowen, W. D.; and Maurice, T. (2003). Sigma 1 Receptor-Related Neuroactive Steroids Modulate Cocaine-Induced Reward. 23(9): 3572.

- Harper's illustrated Biochemistry, 27th edition, Ch.41 "The Diversity of the Endocrine system"

- Roczniki Akademii Medycznej w Białymstoku · Vol. 48, 2003 Annales Academiae Medicae Bialostocensis Incidence of elevated LH/FSH ratioin polycystic ovary syndrome women with normo- and hyperinsulinemiaBanaszewska B, Spaczyński RZ, Pelesz M, Pawelczyk L

- O. Hechter, A. Grossman and R.T. Chatterton Jr (1887). "Relationship of dehydroepiandrosterone and cortisol in disease". Medical Hypotheses. 49 (1): 85–91. PMID 9247914.

- Oberbeck R, Benschop RJ, Jacobs R, Hosch W, Jetschmann JU, Schürmeyer TH, Schmidt RE and Schedlowski M. (1998). "Endocrine mechanisms of stress-induced DHEA-secretion". PubMed.gov. 21: 148–53.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Peter Gallagher BSc(Hons) and Allan Young MB, ChB, MPhil, Ph.D, MRCPsych (2002). "Cortisol/DHEA Ratios in Depression". Neuropsychopharmacology. 26.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wolkowitz, O. M.; Kramer, J. H.; Reus, V. I.; et al. (2003). "DHEA treatment of Alzheimer's disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". Neurology. 60 (7): 1071–6. PMID 12682308.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wolkowitz, O. M.; Reus, V. I.; Keebler, A.; et al. (2006). "Double-blind treatment of major depression with dehydroepiandrosterone". Psychopharmacology. 188 (4). bo-controlled study: 541–551. doi:10.1007/s00213-005-0136-y. PMID 16231168.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - Young, E. A.; Haskett, R. F.; Grunhaus, L.; Weinberg, VM; Watson, SJ; Akil, H; et al. (1994). "Increased evening activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in depressed patients". Archives of General Psychiatry. 51 (9): 701–707. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950090033005. PMID 8080346.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last4=(help). - Morgan, C. A.; Hazlett, G. A.; Rasmusson, A.; Hoyt, G; Zimolo, Z; Charney, D; et al. (2004). "Relationships Among Plasma Dehydroepiandrosteron Sulfate and Cortisol Levels, Symptoms of Dissociation and Objective Performance in Humans Exposed to Acute Stress". Archive of General Psychiatry. 61 (8): 819–825. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.819. PMID 15289280.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last4=(help). - Morgan, C. A.; Rasmusson, A.; Pitrzak, R. H.; Coric, V.; Southwick, S. M. (2009). "Relationships among Plasma Dehydroepiandrosterone and Dehydroepiandrosterone Sulfate, Cortisol, Symptoms of Dissociation and Objective Performance in Humans exposed to Underwater Navigation Stress". Biological Psychiatry. 66 (4): 334–340. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.04.004. PMID 19500775..

- Wallace, M. B.; Lim, J.; Cutler, A.; Bucci, L. (1999). "Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone vs androstenedione supplementation in men". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 31 (12): 1788–92. doi:10.1097/00005768-199912000-00014. PMID 10613429.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Casson PR, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation augments ovarian stimulation in poor responders: a case series. Hum Reprod, 2000;15:2129-2132.

- "DHEA: Treatment for Infertility".

- "Increasing Fertility Threefold".

- Gleicher N., Ryan, E., Weghofer, A., Blanco-Mejia, S., and Barad, D.H. (2009). "Miscarriage rates after dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) supplementation in women with diminished ovarian reserve: a case control study". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2009, 7:108

- Gleicher N, Weghofer, A, and Barad, D.H. (2010). "Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) reduces embryo aneuploidy: direct evidence from preimplantation genetic screening (PGS)". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2010, 8:140

- Barrett-Connor, E.; Khaw, K. T.; Yen, S. S. (1986). "A prospective study of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, mortality, and cardiovascular disease". N. Engl. J. Med. 315 (24): 1519–24. doi:10.1056/NEJM198612113152405. PMID 2946952.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Arnlöv, J.; Pencina, M. J.; Amin, S.; et al. (2006). "Endogenous sex hormones and cardiovascular disease incidence in men". Ann. Intern. Med. 145 (3): 176–84. PMID 16880459.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Boggs, Will. "DHEA Restores Oxidative Balance in Type 2 Diabetes". Medscape. Archived from the original on 2008-01-07. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- Yang, N. C.; Jeng, K. C.; Ho, W. M.; Hu, M. L. (2002). "ATP depletion is an important factor in DHEA-induced growth inhibition and apoptosis in BV-2 cells". Life Sci. 70 (17): 1979–88. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(01)01542-9. PMID 12148690.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Schulz, S.; Klann, R. C.; Schönfeld, S.; Nyce, J. W. (1992). "Mechanisms of cell growth inhibition and cell cycle arrest in human colonic adenocarcinoma cells by dehydroepiandrosterone: role of isoprenoid biosynthesis". Cancer Res. 52 (5): 1372–6. PMID 1531325.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Loria, R. M. (2002). "Immune up-regulation and tumor apoptosis by androstene steroids". Steroids. 67 (12): 953–66. doi:10.1016/S0039-128X(02)00043-0. PMID 12398992.

- Tworoger, S. S.; Missmer, S. A.; Eliassen, A. H.; et al. (2006). "The association of plasma DHEA and DHEA sulfate with breast cancer risk in predominantly premenopausal women". Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 15 (5): 967–71. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0976. PMID 16702378.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Key, T.; Appleby, P.; Barnes, I.; Reeves, G. (2002). "Endogenous sex hormones and breast cancer in postmenopausal women: reanalysis of nine prospective studies". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 94 (8): 606–16. PMID 11959894.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fukui, M.; Kitagawa, Y.; Nakamura, N.; Kadono, M.; Yoshida, M.; Hirata, C.; Wada, K.; Hasegawa, G.; Yoshikawa, T. (2005). "Serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate concentration and carotid atherosclerosis in men with type 2 diabetes". Atherosclerosis. 181 (2): 339–344. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.01.014. PMID 16039288.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Martina, V.; Benso, A.; Gigliardi, V. R.; et al. (2006). "Short-term dehydroepiandrosterone tereatment increases platelet cGMP production in elderly male subjects". Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.). 11 (March, 64(3)): 260–4. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02454.x. PMID 16487434.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - See also Symposium On Role of Prasterone In Aging, Annals of the New York Academy of Science vol. 774, pp. 1-350 (1995)

- Enomoto, Mika; Adachi, H; Fukami, A; Furuki, K; Satoh, A; Otsuka, M; Kumagae, S; Nanjo, Y; Shigetoh, Y (2008). "Serum Dehydroepiandrosterone Sulfate Levels Predict Longevity in Men: 27-Year Follow-Up Study in a Community-Based Cohort (Tanushimaru Study)". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 56 (6): 994–8. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01692.x. PMID 18422949.

- "DHEA: the last elixir". Prescrire international. 11 (60): 118–23. 2002. PMID 12199273.

- Calfee, R.; Fadale, P. (2006). "Popular ergogenic drugs and supplements in young athletes". Pediatrics. 117 (3): e577–89. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1429. PMID 16510635.

In 2004, a new Steroid Control Act that placed androstenedione under Schedule III of controlled substances effective January 2005 was signed. DHEA was not included in this act and remains an over-the-counter nutritional supplement.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tokish, J. M.; Kocher, M. S.; Hawkins, R. J. (2004). "Ergogenic aids: a review of basic science, performance, side effects, and status in sports". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 32 (6): 1543–53. doi:10.1177/0363546504268041. PMID 15310585.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Medline Plus. "DHEA". Drugs and Supplements Information. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- Medscape (2010). "DHEA Oral". Drug Reference. WebMD LLC. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- Sahelian, M.D., Ray (2005). "Honest DHEA Supplement Information". DHEA: A Practical Guide, Mind Boosters, and Natural Sex Boosters. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1998 Oct; 78(5):466-71

- Tissandier, O.; Péres, G.; Fiet, J.; Piette, F. (2001). "Testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone, insulin-like growth factor 1, and insulin in sedentary and physically trained aged men". European Journal of Applied Physiology. 85 (1–2): 177–184. doi:10.1007/s004210100420. PMID 11513313..

- J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2002 Apr; 57(4):B158-65

- Mattison, Julie A.; Lane, Mark A.; Roth, George S.; Ingram, Donald K. (2003). "Calorie restriction in rhesus monkeys". Experimental Gerontology. 38 (1–2): 35–46. doi:10.1016/S0531-5565(02)00146-8. PMID 12543259..

- Roberts, E. (1999). "The importance of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate in the blood of primates: a longer and healthier life?". Biochemical Pharmacology. 57 (4): 329–346. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(98)00246-9. PMID 9933021..

- S. 762: A bill to include dehydroepiandrosterone as an anabolic steroid, from http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/thomas . Accessed Sept. 9, 2009.

- S. 2470: Dehydroepiandrosterone Abuse Reduction Act of 2007 (GovTrack.us)

- Dr. Michael Colgin. The Deal With D.H.E.A. Vista Magazine Online. www.vistamag.com

- World Anti-Doping Agency

- Memphis Grizzlies' O.J. Mayo gets 10-game drug suspension - ESPN. January 27, 2011.

External links

- Information on DHEA from the Mayo Clinic

- DHEA in elderly women and DHEA or testosterone in elderly men, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2006. "Neither DHEA nor low-dose testosterone replacement in elderly people has physiologically relevant beneficial effects on body composition, physical performance, insulin sensitivity, or quality of life."

- DHEA, from the Skeptic's Dictionary

- ChemSub Online: Dehydroepiandrosterone - DHEA

| Endogenous steroids | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precursors | |||||||

| Corticosteroids |

| ||||||

| Sex steroids |

| ||||||

| Neurosteroids |

| ||||||

| Others | |||||||