This is an old revision of this page, as edited by JoeBot (talk | contribs) at 17:27, 5 April 2006 (typo fix: "similair/similiar" to "similar" using AWB). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:27, 5 April 2006 by JoeBot (talk | contribs) (typo fix: "similair/similiar" to "similar" using AWB)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

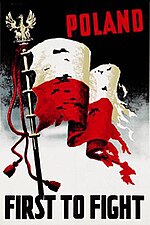

The European theater of World War II opened with the invasion of Poland by German armed forces in the 1939 Polish September Campaign. After Poland had been overrun, she managed to establish a government-in-exile, armed forces and an intelligence service outside Poland, contributing to the Allied effort throughout the war. Poland never made a general surrender and was the only German-occupied country which did not produce a puppet government that collaborated with the Nazis.

Polish September Campaign

Further information: Polish September CampaignThe Polish September Campaign was the World War II invasion of Poland by military forces of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union and by a small German-allied Slovak contingent. The invasion of Poland marked the start of World War II in Europe as Poland's western allies, the United Kingdom and France, declared war on Germany on September 3. The campaign began on September 1 1939, one week after the signing of the secret Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, and ended on October 6 1939, with Germany and the Soviet Union occupying the entirety of Poland.

German personnel losses were about ~16,000 KIA, and the loss of over ~30% of armored vehicles during the campaign was one of the reasons the plans for an immediate attack west were discarded.

Underground resistance in Poland

| Part of a series on the |

| Polish Underground State |

|---|

History of Poland 1939–1945 History of Poland 1939–1945 |

| Authorities |

|

Political organizations Major parties Minor parties Opposition |

|

Military organizations Home Army (AK) Mostly integrated with Armed Resistance and Home Army Partially integrated with Armed Resistance and Home Army

Non-integrated but recognizing authority of Armed Resistance and Home Army Opposition |

| Related topics |

The main resistance force in the Nazi occupied Poland was the Armia Krajowa ("Home Army"; abbreviated "AK"), numbered some 200,000-300,000 soldiers at its peak as well as many more sympathizers. The Home Army coordinated its operations with the the exiled Polish Government in London and its activity concentrated on sabotage, diversion and intelligence gathering. Its combat activity was low until 1943 as the army was avoiding the suiciadal warfare and preserving its very limited force for the later fights that sharply increased when the Nazi war machine started to crumble in the wake of the successes of the Red Army in the Eastern Front and the Home Army started a nationwide uprising (Operation Tempest) against Nazi forces. Before that the AK units carried out thousands of raids, intelligence operations, bombed hundreds of railway shipments, participated in many clashes and battles with the German police and Wehrmacht units, and conducted tens of thousands of acts of sabotage against German industry. AK also conducted "vengeance" operations to assassinate Gestapo officials responsible for Nazi terror. Following the 1941 German attack on the USSR, the Home Army assisted Soviet Union's war effort by sabotaging German advance into Soviet territories and providing intelligence about deployment and movement of German forces. Following 1943 its direct combat activity increased sharply. German losses to the Polish partisans ranged at 850-1700 per month in early 1944 compared to about 250-320 per months in 1942.

A distinct from the Home Army there was an underground ultra-nationalist resistance force called Narodowe Siły Zbrojne (NZS or National Armed Forces) The ultra-chauvinist and anti-Semite stance of this army, is well established and remains an issue of a painful debate (as well as the degree of complicity of the Home Army in the fate of Jews during the Holocaust events in Poland). At different times NZS was fighting the Nazi forces as well as the forces of the pro-Soviet communist resistance (see below), the Jewish resistance and the Red Army.

Armia Ludowa a the Soviet proxy fighting force was another group that was unrelated to the Polish Government in Exile. As of July, 1944 it numbered about 6,000 soldiers (estimates vary).

There were separate resistance groups organized by the Polish Jews: the right-wing zionist Jewish Fighting Union (ZZW) and the more left-leaning Jewish Combat Organization (ZOB). These organizations cooperated little with each other and their relationship with Polish resistance varied between occasional cooperation (mainly between ZOB and AK) to the armed collisions (mostly between ZZW and NZS).

Intelligence

During a period of over six and a half years, from late December 1932 to the outbreak of World War II, three mathematician-cryptologists (Marian Rejewski, Henryk Zygalski and Jerzy Różycki) at the Polish General Staff's Cipher Bureau in Warsaw had developed a number of techniques and devices — including the "grill" method, Różycki's "clock," Rejewski's "cyclometer" and "card catalog," Zygalski's "perforated sheets," and Rejewski's "cryptologic bomb" (Polish term: bomba, precursor to the later British "Bombe," named after its Polish predecessor) — to facilitate decryption of messages produced on the German "Enigma" cipher machine. A few weeks before the outbreak of World War II, on July 25, 1939, near Pyry in the Kabaty Woods just south of Warsaw, Poland disclosed her achievements to France and the United Kingdom, which had, up to that time, failed in all their own efforts to crack the German military Enigma cipher.

Had Poland not shared her results at Pyry, the United Kingdom would, at the very least, have been delayed by one or two years in reading Enigma, and could well have been unable to read it at all. In the event, intelligence gained from this source, codenamed ULTRA, was extremely valuable in the Allied prosecution of the war, although the exact influence of ULTRA on the course of the war has been a subject of debate. Some have argued that it decided the very outcome of the war itself, but more recently the view that ULTRA hastened the defeat of Germany by a period of time (between 6 months and 4 years) has found widespread acceptance.

As early as 1940, Polish agents (see Witold Pilecki) penetrated German concentration camps, including Auschwitz, and informed the world about Nazi atrocities.

Home Army (Polish: Armia Krajowa) intelligence was vital in locating and destroying (18 August 1943) the German rocket facility at Peenemunde and in gathering information about Germany's V-1 buzzbomb and V-2 rocket. The Home Army delivered to the United Kingdom key V-2 parts, after a V-2 rocket, fired 30 May 1944, crashed near a German test facility at Sarnaki on the Bug River and was recovered by the Home Army. On the night of 25-26 July, 1944, the crucial parts were flown from occupied Poland to the United Kingdom in an RAF plane, along with detailed drawings of parts too large to fit in the plane (see Home Army and V1 and V2). Analysis of the German rocket became vital to improving Allied anti-V-2 defenses.

Polish intelligence cooperated with the other Allies in every European country and operated one of the largest intelligence networks in Nazi Germany. Many Poles also served in other Allied intelligence services, including the celebrated Krystyna Skarbek ("Christine Granville") in the United Kingdom's Special Operations Executive.

Polish Armed Forces in the West

Further information: Polish Armed Forces in the WestArmy

at the height of their power

| Deserters from the German Wehrmacht | 89,300 | (35.8%) |

| Evacuees from the USSR in 1941 | 83,000 | (33.7%) |

| Evacuees from France in 1940 | 35,000 | (14.0%) |

| Liberated POWs | 21,750 | (8.7%) |

| Escapees from occupied Europe | 14,210 | (5.7%) |

| Recruits in liberated France | 7,000 | (2.8%) |

| Polonia from Argentina, Brazil and Canada | 2,290 | (0.9%) |

| Polonia from United Kingdom | 1,780 | (0.7%) |

| Total | 249,000 | |

| Note: Until July 1945, when recruitment was halted, some 26,830 Polish soldiers were declared KIA or MIA or had died of wounds. After that date, an additional 21,000 former Polish POWs were inducted. | ||

Source: Reference #4

After the country's defeat in the 1939 campaign, the Polish government in exile quickly organized in France a new army of about 80,000 men. In 1940 a Polish Highland Brigade took part in the Battle of Narvik (Norway), and two Polish divisions (First Grenadier Division, and Second Infantry Fusiliers Division) took part in the defense of France, while a Polish motorized brigade and two infantry divisions were in process of forming. A Polish Independent Carpathian Brigade was formed in French-mandated Syria, to which many Polish troops had escaped from Romania. The Polish Air Force in France comprised eighty-six aircraft in four squadrons, one and a half of the squadrons being fully operational while the rest were in various stages of training.

After the fall of France, many Polish personnel had died in the fighting or been interned in Switzerland. Nevertheless, General Władysław Sikorski, Polish commander-in-chief and prime minister, was able to evacuate many Polish troops to the United Kingdom. In 1941, pursuant to an agreement between the Polish government in exile and Joseph Stalin, the Soviets released many Polish citizens, from whom a 75,000-strong army was formed in the Middle East under General Władysław Anders ("Anders' Army").

The Polish armed forces in the west fought under the British command and numbered 195,000 in March 1944 and 165,000 at the end of that year, including about 20,000 personnel in the Polish Air Force and 3,000 in the Polish Navy. At the end of WWII, the Polish Armed Forces in the west numbered 195,000 and by July 1945 had increased to 228,000, most of the newcomers being released prisoners of war and ex-labor-camp inmates.

Air Force

The Polish Air Force fought in the Battle of France as one fighter squadron GC 1/145, several small units detached to French squadrons, and numerous flights of industry defence (in total, 133 pilots, who achieved 55 victories at a loss of 15 men).

Later, Polish pilots fought in the Battle of Britain, where the Polish 303 Fighter Squadron achieved the highest number of kills of any Allied squadron. From the very beginning of the war, the Royal Air Force (RAF) had welcomed foreign pilots to supplement the dwindling pool of British pilots. On 11 June 1940, the Polish Government in Exile signed an agreement with the British Government to form a Polish Army and Polish Air Force in the United Kingdom. The first two (of an eventual ten) Polish fighter squadrons went into action in August 1940. Four Polish squadrons eventually took part in the Battle of Britain (300 and 301 Bomber Squadrons; 302 and 303 Fighter Squadrons), with 89 Polish pilots. Together with more than 50 Poles fighting in British squadrons, a total of 145 Polish pilots defended British skies. Polish pilots were among the most experienced in the battle, most of them having already fought in the 1939 September Campaign in Poland and the 1940 Battle of France. Additionally, prewar Poland had set a very high standard of pilot training. The 303 Squadron, named after the Polish-American hero, General Tadeusz Kościuszko, achieved the highest number of kills (126) of all fighter squadrons engaged in the Battle of Britain, even though it only joined the combat on August 30, 1940: these 5% of pilots were responsible for a phenomenal 12% of total victories in the Battle.

The Polish Air Force also fought in 1943 in Tunisia (Polish Fighting Team, so called "Skalski's Circus") and in raids on Germany (1940-45). In the second half of 1941 and early 1942, Polish bomber squadrons were the sixth part of forces available to RAF Bomber Command (later they suffered heavy losses, with little replenishment possibilities). Polish aircrew losses serving with Bomber Command 1940-45 were 929 killed. Ultimately 8 Polish fighter squadrons were formed within the RAF and had claimed 629 Axis aircraft destroyed by May 1945. By war's end, there were 14,000 Polish airmen in 15 RAF squadrons and in the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF).

Polish squadrons in the United Kingdom:

- No. 300 "Masovia" Polish Bomber Squadron (Ziemi Mazowieckiej)

- No. 301 "Pomerania" Polish Bomber Squadron (Ziemi Pomorskiej)

- No. 302 "City of Poznań" Polish Fighter Squadron (Poznański)

- No. 303 "Kościuszko" Polish Fighter Squadron (Warszawski imienia Tadeusza Kościuszki)

- No. 304 "Silesia" Polish Bomber Squadron (Ziemi Śląskiej imienia Ksiecia Józefa Poniatowskiego)

- No. 305 "Greater Poland" Polish Bomber Squadron (Ziemi Wielkopolskiej imienia Marszałka Józefa Piłsudskiego)

- No. 306 "City of Toruń" Polish Fighter Squadron (Toruński)

- No. 307 "City of Lwów" Polish Fighter Squadron (Lwowskich Puchaczy)

- No. 308 "City of Kraków" Polish Fighter Squadron (Krakowski)

- No. 309 "Czerwień" Polish Fighter-Reconnaissance Squadron (Ziemi Czerwieńskiej)

- No. 315 "City of Dęblin" Polish Fighter Squadron (Dębliński)

- No. 316 "City of Warsaw" Polish Fighter Squadron (Warszawski)

- No. 317 "City of Wilno" Polish Fighter Squadron (Wileński)

- No. 318 "City of Gdańsk" Polish Fighter-Reconnaissance Squadron (Gdański)

- No. 663 Polish Artillery Observation Squadron

- Polish Fighting Team (Skalski's Circus)

Navy

Just on the eve of war, most of the major Polish Navy ships had been sent for safety to the British Isles. There they fought alongside the Royal Navy. At various stages of the war, the Polish Navy comprised two cruisers and a large number of smaller ships, including three destroyers and two submarines that had left the Baltic Sea in late August 1939.

- Cruisers:

- ORP Dragon (Danae class)

- ORP Conrad (Danae class)

- Destroyers:

- ORP Wicher (Wind) (Wicher class)

- ORP Burza (Storm) (Wicher class)

- ORP Grom (Thunder) (Grom class)

- ORP Błyskawica (Lightning) (Grom class)

- ORP Garland (G class)

- ORP Orkan (M class)

- ORP Ouragan (Hurricane, also known in some Polish sources as Huragan) (Bourrasque class)

- ORP Piorun (Thunderbolt) (N class)

- Escort destroyers

- ORP Krakowiak (Cracovian) (Hunt class)

- ORP Kujawiak (Kujawian) (Hunt class)

- ORP Ślązak (Silesian) (Hunt class)

- Submarines:

- ORP Orzeł (Eagle) (Orzel Class)

- ORP Sęp (Vulture) (Orzel Class)

- ORP Jastrząb (Hawk) (S class)

- ORP Wilk (Wolf) (Wilk class)

- ORP Ryś (Lynx) (Wilk class)

- ORP Żbik (Wildcat) (Wilk class)

- ORP Dzik (Boar) (U class)

- ORP Sokół (Falcon) (U class)

- heavy minelayers:

The above list does not include a number of minor ships, transports, merchant-marine auxiliary vessels, and patrol boats.

The Polish Navy fought with great distinction alongside the other Allied navies in many important and successful operations, including those conducted against the German battleship, Bismarck.

Polish Armed Forces in the East

Further information: Polish Armed Forces in the EastThe Soviet Union created in Moscow a Union of Polish Patriots (ZPP) as communist puppet counter-govenment to the Polish government in exile. At the same time a parallel Polish People's Army (LWP was created which by the end of the war numbered about 200,000 troops .

There pro-Soviet Polish resistance Armia Ludowa was integrated with Polish People's Army at the end of the war.

Polish army units on the Eastern Front included the 1st, the 2nd and the 3rd Polish Armies (the latter was later merged with the second), with 10 infantry divisions and 5 armored brigades. Many of their soldiers were forced into military formations from former Home Army units taken prisoner during Soviet advances into Poland, while others joined in order to escape labour camps, prisons and Gulags in Soviet Union. These units were led by the Soviet commanders, appointed by the Soviets and fought under the Soviet general command,. In Air Force of those formations 90 % of officers and engineers were Russians and Soviet officers, the situation was similar in armored formation. In 2nd Polish Army they consisted 60% of officers and engineers, and in the 1st 40%. In the command staff and training the percentage of Soviets and Russians was about 70 to 85%. As a result the majority of Poles viewed these formations as simply Russians who wore Polish uniforms . Even at the time of formation of those units Soviets arrested hundreds of Polish soldiers that spoke badly about Soviet Union, singed improper patriotic songs, or talked about "enemy propaganda". Special political officers had overseen Polish soldiers, as they weren't trusted. Poltical officers were completely made of Soviets and didn't contain Poles.

The 1st Army was integrated in the 1st Belorussian Front with which it entered Poland from the Soviet territory in 1944. As Soviets pressed into Polish territory they forcefully conscripted Home Army soldiers after their units were defeated in fighting and their commanders imprisoned or executed. After July 1944 the Soviets engaged in purges, in which former Home Army soldiers were mass murdered after military trials, in some cases the places where those atrocities were performed were the same that Nazi's used. Ordered so by the Soviet leadership it did not advance towards Warsaw as Germans suppressed the Warsaw Uprising fought mainly by AK, and in January 1945 after Germans crushed the uprising the 1st Army participated in the Soviet Warsaw offensive that finally drove the Nazi occupation out of the ruined city. It took part in battles for Bydgoszcz, Kolobrzeg (Kolberg), Gdańsk (Danzig) and Gdynia loosing 20,000 people in winter 1944-45 battles. In April-May 1945 the 1st Army fought in the final capture of Berlin. The 2nd Polish Army fought within the Soviet 1st Ukrainian Front and took part in the Prague Offensive. In the final operations of the war the losses of the two armies of the LWP amounted to 32,000.

Battles

Major battles and campaigns in which Polish regular forces took part:

- Polish September Campaign (1939)

- British campaign in Norway (Battle of Narvik)

- French Campaign

- Battle of Britain

- Battle of the Atlantic

- Battle of Tobruk

- Operation Jubilee (Battle of Dieppe)

- Battle of Lenino

- Battle of Normandy (D-Day)

- Battle of Monte Cassino

- Battle of Falaise

- Operation Market Garden (Battle of Arnhem: "A Bridge Too Far")

- Battle of Ancona

- Battle of Bologna

- Battle of Berlin

- Prague Offensive

- Polish underground actions:

Technical inventions

- Replicas of the German Enigma cipher machine had been produced at the start of 1933 to the specifications of Polish mathematician-cryptologist Marian Rejewski, and two machines of the current model were given to the British and French just before the outbreak of war in 1939. Rejewski and his two cryptologist colleagues also invented the cryptological bomb, perforated Zygalski sheets, and other techniques and devices for breaking Enigma ciphers.

- Józef Kosacki invented the Polish mine detector, which would be used by the Allies throughout the war.

- The Vickers Tank Periscope MK.IV was invented by engineer Rudolf Gundlach and patented in 1936 as the Gundlach Peryskop obrotowy. It was copied by the British and used in most tanks of WW II, including the Soviet T-34, the British Crusader, Churchill, Valentine and Cromwell, and the American M4 Sherman. The main advantage of this periscope was that the tank commander no longer had to turn his head in order to look backwards. The design was also later used extensively by the Germans.

- A bomb-hatch system was invented by Władysław Świątecki in the 1930s and was used in the prewar Polish PZL P.37 Elk (Łoś) bomber. In 1940 Świątecki turned his invention over to the British, who used it in most British bombers. In 1943, an updated version was created by Jerzy Rudlicki for the American B-17 Flying Fortress.

- A rubber windshield wiper was invented by the Polish pianist Józef Hofmann.

- Henryk Magnuski, a Polish engineer working for Motorola, in 1940 invented the SCR-300 radio, the first small radio receiver/transmitter to have manually-set frequencies. It was used extensively by the American Army and was nicknamed the walkie-talkie.

- The Polish Home Army was probably the only WWII resistance movement which produced large quantities of weaponry and munitions. In addition to pre-war designs like Vis pistol, there were also the Błyskawica, Bechowiec, KIS and Polski Sten machine pistols, designed and produced by the underground facilities. In addition, large amounts of filipinka and sidolówka hand grenades were developed and manufactured in the underground. Finally, during the Warsaw Uprising the Polish engineers built several armoured cars which also took part in the fighting.

References

In-line

- ^ Steven J Zaloga (1982). "The Underground Army". Polish Army, 1939-1945. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0850454174.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Piotrowski, Tadeusz (1997). "Polish Collaboration". Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947. McFarland & Company. pp. 77–142. ISBN 0786403713.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - "Organized murders of Jews committed by varios underground formations began toward the end of 1942, and occured quite frequently thereafter... The largest number of such murders were perpetrated by the units of National Armed Forces ; but some groups of the Home Army also shared this guilt. Obviously most of these units may have belonged to that part of the National Armed forces which joined the Home Army...." from Piotrowski, same chapter

- "Clearly the NSZ attacked and killed GL-AL members and took pride in these "patrotic" actions. Since these units contained Jews, Jews were also killed.", from Piotrowski, same chapter

- " Relations reached a peak of tensions when a report was received that a unit of the Jewish Combat Organization had been attacked by the "Eagle" unit of the NSZ or AK and eleven of its twenty-four memmers killed. The Jewsih Combat Organization learnt that similar bands had murdered 200 Jews who had been in hiding. Further facts were also uncovered later conserning the collaboration of NSZ bands with the Gestapo in an "action" to kill "Jews and Communists". NSZ bandits even murdered Dmocratic personalities connected with AK, especially those of Jewish origin. The NSZ-men organized a special group to hunt down the Jews and kill them off.", from Piotrowski, same chapter

- ^ Steven J Zaloga (1982). "The Polish People's Army". Polish Army, 1939-1945. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0850454174.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)

General

- Władysław Anders: An Army in Exile: The Story of the Second Polish Corps, 1981, ISBN 0898390435.

- Margaret Brodniewicz-Stawicki: For Your Freedom and Ours: The Polish Armed Forces in the Second World War, Vanwell Publishing, 1999, ISBN 1551250357.

- Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski: Secret Army, Battery Press, 1984, ISBN 0898390826.

- George F. Cholewczynski (1993). Poles Apart. Sarpedon Publishers. ISBN 1853671657.

- George F. Cholewczynski (1990). De Polen Van Driel. Uitgeverij Lunet. ISBN 9071743101.

- Jerzy B. Cynk: The Polish Air Force at War: The Official History, 1939-1943, Schiffer Publishing, 1998, ISBN 076430559X.

- Jerzy B. Cynk: The Polish Air Force at War: The Official History, 1943-1945, Schiffer Publishing, 1998, ISBN 0764305603.

- Robert Gretzyngier: Poles in Defence of Britain, London 2001, ISBN 190230454.

- Norman Davies: Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw, Viking Books, 2004, ISBN 0670032840.

- Norman Davies, God's Playground, Oxford University Press, 1981

- Lynne Olson, Stanley Cloud: A Question of Honor: The Kosciuszko Squadron: Forgotten Heroes of World War II, Knopf, 2003, ISBN 0375411976.

- Józef Garliński: Poland in the Second World War, Hippocrene Books, 1987, ISBN 0870523724.

- Jan Karski: Story of a Secret State, Simon Publications, 2001, ISBN 1931541396.

- Jan Koniarek, Polish Air Force 1939-1945, Squadron/Signal Publications, 1994, ISBN 0897473248.

- Stefan Korboński, Zofia Korbońska, F. B. Czarnomski: Fighting Warsaw: the Story of the Polish Underground State, 1939-1945, Hippocrene Books, 2004, ISBN 0781810353.

- Władysław Kozaczuk, Enigma: How the German Machine Cipher Was Broken, and How It Was Read by the Allies in World War Two, edited and translated by Christopher Kasparek, University Publications of America, 1984, ISBN 0890935475. (This remains the standard reference on the Polish part in the Enigma-decryption epic.)

- Władysław Kozaczuk, Jerzy Straszak: Enigma: How the Poles Broke the Nazi Code, Hippocrene Books; February 1 2004, ISBN 078180941X.

- Michael Alfred Peszke, Battle for Warsaw, 1939-1944, East European Monographs, 1995, ISBN 0880333243.

- Michael Alfred Peszke, Poland's Navy, 1918-1945, Hippocrene Books, 1999, ISBN 0781806720.

- Michael Alfred Peszke, The Polish Underground Army, the Western Allies, and the Failure of Strategic Unity in World War II, foreword by Piotr S. Wandycz, Jefferson, NC, McFarland & Company, 2005, ISBN 078642009X. Google Print

- Polish Air Force Association: Destiny Can Wait: The Polish Air Force in the Second World War, Battery Press, 1988, ISBN 089839113X.

- Harvey Sarner: Anders and the Soldiers of the Second Polish Corps, Brunswick Press, 1998, ISBN 1888521139.

- Stanisław Sosabowski: Freely I Served, Battery Press Inc, 1982, ISBN 0898390613.

- E. Thomas Wood, Stanislaw M. Jankowski: Karski: How One Man Tried to Stop the Holocaust, Wiley, 1996, ISBN 0471145734.

- Steven J. Zaloga: Poland 1939: The Birth of Blitzkrieg, Osprey Publishing, 2004, ISBN 1841764086.

- Steven J. Zaloga: The Polish Army 1939-1945, Osprey Publishing, 1982, ISBN 0850454174.

- Adam Zamoyski: The Forgotten Few: The Polish Air Force in the Second World War, Pen & Sword Books, 2004, ISBN 1844150909.

See also

- History of Poland (1939-1945),

- List of Polish armies in WWII

- List of Polish divisions in WWII

- Polish Secret State

- Polish government in exile

- Western betrayal

- Polish resistance movement

- Many books and articles on Soviet and Polish tanks and armor by author and military historian Janusz Magnuski

- Blackhawk (comics)

External links

- Military contribution of Poland to World War II, Polish Ministry of Defence official page

- The Poles on the Fronts of WW2

- Polish units in defence of France, 1939-1940

- Polish Squadrons Remembered

- Veterans Monument in Buffalo, NY

- The History Of Poland: The Second World War

- "To Return To Poland Or Not To Return" - The Dilemma Facing The Polish Armed Forces At The End Of The Second World War, Thesis by Dr Mark Ostrowski

- Gilbert J. Mros: This V-E Day say 'dziekuje' to the Poles

- Listen to Lynn Olsen & Stanley Cloud, authors of "A Question of Honor," speak about the "Kościuszko" Squadron and Polish contribution to World War II here.