This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 175.100.188.30 (talk) at 16:43, 25 February 2012. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:43, 25 February 2012 by 175.100.188.30 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Ape (disambiguation).

| Hominoidea Temporal range: Late Oligocene - Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pranav | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Subclass: | Theria |

| Infraclass: | Eutheria |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorrhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Parvorder: | Catarrhini |

| Superfamily: | Hominoidea Gray, 1825 |

| Families | |

|

Hylobatidae | |

Apes are Old World anthropoid mammals, more specifically a clade of tailless catarrhine primates, belonging to the biological superfamily Hominoidea. The apes are native to Africa and South-east Asia. Apes are the world's largest primates; the orangutan, an ape, is the world's largest living arboreal animal. Hominoids are traditionally forest dwellers, although chimpanzees may range into savanna, and the extinct australopithecines are famous for being savanna inhabitants, inferred from their morphology. Humans inhabit almost every terrestrial habitat.

Hominoidea contains two families of living (extant) species:

- Hylobatidae consists of four genera and sixteen species of gibbon, including the lar gibbon and the siamang. They are commonly referred to as lesser apes.

- Hominidae consists of orangutans, gorillas, common chimpanzees, bonobos and humans. Alternatively, the hominidae family are collectively described as the great apes.

Members of the superfamily are called hominoids (not to be confused with "hominids" or "hominins").

Some or all hominoids are also called "apes". However, the term "ape" is used in several different senses. It has been used as a synonym for "monkey" or for any tailless primate with a humanlike appearance. Thus the Barbary macaque, a kind of monkey, is popularly called the "Barbary ape" to indicate its lack of a tail. Biologists have used the term "ape" to mean a member of the superfamily Hominoidea other than humans, or more recently to mean all members of the superfamily Hominoidea, so that "ape" becomes another word for "hominoid". See also Primate: Historical and modern terminology.

Except for gorillas and humans, hominoids are agile climbers of trees. Their diet is best described as vegetarian or omnivorous, consisting of leaves, nuts, seeds and fruits, including grass seeds, and in most cases other animals, either hunted or scavenged (or farmed in the case of humans), along with anything else available and easily digested.

Most nonhuman hominoids are rare or endangered. The chief threat to most of the endangered species is loss of tropical rainforest habitat, though some populations are further imperiled by hunting for bushmeat.

Historical and modern terminology

"Ape", from Old English apa, is possibly an onomatopoetic imitation of animal chatter. The term has a history of rather imprecise usage. Its earliest meaning was a tailless (and therefore exceptionally human-like) nonhuman primate. The original usage of "ape" in English might have referred to the baboon, an Old World monkey. Two tailless species of macaque have common names including "ape": the Barbary ape of North Africa (introduced into Gibraltar), Macaca sylvanus, and the Sulawesi black ape or Celebes crested macaque, M. nigra.

As zoological knowledge developed, it became clear that taillessness occurred in a number of different and otherwise unrelated species. The term "ape" was then used in two different senses, as shown in the 1910 Encyclopædia Britannica entry. Either "ape" was still used for a tailless humanlike primate or it became a synonym for "monkey".

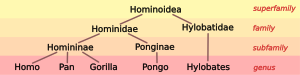

Sir Wilfrid Le Gros Clark was one of the primatologists who developed the idea that there were "trends" in primate evolution and that the living members of the order could be arranged in a series, leading through "monkeys" and "apes" to humans. Within this tradition, "ape" refers to all the members of the superfamily Hominoidea, except humans. Thus "apes" are a paraphyletic group, meaning that although all the species of apes descend from a common ancestor, the group does not include all the descendants of that ancestor, because humans are excluded. The diagram below shows the currently accepted evolutionary relationships of the Hominoidea, with the apes marked by a bracket.

|

apes |

The "apes" are traditionally divided further into the "lesser apes" and the "great apes":

|

great apes lesser apes |

In summary, there are three common uses of the term "ape": non-biologists may not distinguish between "monkeys" and "apes", or may use "ape" for any tailless monkey or nonhuman hominoid, whereas biologists traditionally used the term "ape" for all non-human hominoids as shown above.

In recent years biologists have generally preferred to use only monophyletic groups in classifications, that is only groups which include all the descendants of a common ancestor. The superfamily Hominoidea is one such group (or "clade"). Some then use the term "ape" to mean all the members of the superfamily Hominoidea. For example, in a 2005 book, Benton wrote "The apes, Hominoidea, today include the gibbons and orang-utan ... the gorilla and chimpanzee ... and humans". The group traditionally called "apes" by biologists is then called the "nonhuman apes".

See the section History of hominoid taxonomy below for a discussion of changes in scientific classification and terminology.

Biology

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The "lesser apes" are the gibbon family, Hylobatidae with sixteen medium-sized species. Their major differentiating characteristic is their long arms, which they use to brachiate through the trees. As an evolutionary adaptation to this arboreal lifestyle, their wrists are ball and socket joints. The largest of the gibbons, the siamang, weighs up to 14 kg (31 lb). In comparison, the smallest "great ape" is the common chimpanzee at 40 to 65 kg (88 to 143 lb).

The "great apes" were formerly treated as the family Pongidae. As noted above, this definition makes the Pongidae paraphyletic, and does not show that orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees and humans are all more closely related to one another than any of these four groups are to gibbons. Further, current evidence implies that humans share a common extinct ancestor with the chimpanzee line, from which we separated more recently than the gorilla line.

The superfamily Hominoidea falls within Catarrhini, which also includes the Old World monkeys of Africa and Eurasia. Within this group, both families (Hylobatidae and Hominidae) can be distinguished from Old World monkeys by the number of cusps on their molars (hominoids have five—the "Y-5" molar pattern, Old World monkeys have only four in a bilophodont pattern). Hominoids have more mobile shoulder joints and arms due to the dorsal position of the scapula, broad ribcages that are flatter front-to-back, and a shorter, less mobile spine compared to Old World monkeys, with caudal (tail) vertebrae greatly reduced, resulting in complete tail loss in living species. These are all anatomical adaptations to vertical hanging and swinging locomotion (brachiation), as well as better balance in a bipedal pose. However, there are also primates in other families that lack tails, and at least one (the pig-tailed langur) that has been known to walk significant distances bipedally. The front skull is characterised by its sinuses, fusion of the frontal bone and post-orbital constriction.

Although the hominoid fossil record is far from complete, and the evidence is often fragmentary, there is enough to give a good outline of the evolutionary history of humans. The time of the split between humans and other living hominoids used to be thought to have occurred 15 to 20 million years ago. Some species occurring within that time period, such as Ramapithecus, used to be considered as hominins, and possible ancestors of humans. Later fossil finds indicated that Ramapithecus was more closely related to the orangutan, and new biochemical evidence indicated that the last common ancestor of humans and other hominins occurred between 5 and 10 million years ago, and probably in the lower end of that range.

Behaviour and cognition

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Although there had been earlier studies, the scientific investigation of behaviour and cognition in nonhuman members of the superfamily Hominoidea expanded enormously during the latter half of the twentieth century. Major studies of behaviour in the field were completed on the three better-known "great apes", for example by Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey and Birute Galdikas (field work on gibbons and the bonobo is still relatively underdeveloped). These studies have shown that in their natural environments, the nonhuman hominoids show sharply varying social structure: gibbons are monogamous, territorial pair-bonders, orangutans are solitary, gorillas live in small troops with a single adult male leader, while chimpanzees live in larger troops with bonobos exhibiting promiscuous sexual behaviour. Their diets also vary; gorillas are foliovores while the others are all primarily frugivores, although the common chimpanzee does some hunting for meat. Foraging behaviour is correspondingly variable.

All the nonhuman hominoids are generally thought of as highly intelligent, and scientific study has broadly confirmed that they perform outstandingly well on a wide range of cognitive tests - though there is relatively little data on gibbon cognition. The early studies by Wolfgang Köhler demonstrated exceptional problem-solving abilities in chimpanzees, which Köhler attributed to insight. The use of tools has been repeatedly demonstrated; more recently, the manufacture of tools has been documented, both in the wild and in laboratory tests. Imitation is much more easily demonstrated in "great apes" than in other primate species. Almost all the studies in animal language acquisition have been completed with "great apes", and though there is continuing dispute as to whether they demonstrate real language abilities, there is no doubt that they involve significant feats of learning. Chimpanzees in different parts of Africa have developed tools that are used in food acquisition, demonstrating a form of animal culture.

Distinction from monkeys

Apes do not possess a tail, unlike most monkeys. Monkeys are more likely to be in trees and use their tails for balance. Apes are considerably larger than monkeys, with the exception of gibbons, which are smaller than some monkeys. Apes are considered to be more intelligent than monkeys, which are considered to have more primitive brains. Unlike female monkeys which go through the estrous cycle, great apes, including humans, go through a menstrual cycle.

History of hominoid taxonomy

The history of hominoid taxonomy is somewhat confusing and complex. The names of subgroups have changed their meaning over time as new evidence, from fossil discoveries and comparisons of anatomy and DNA sequences, has changed understanding of the relationships between hominoids. There has been a gradual demotion of humans from a special position in the taxonomy to being one branch among many. This history illustrates the growing influence of cladistics (the science of classifying living things by strict descent) on taxonomy.

As of 2006, there are eight extant genera of hominoids. They are the four genera in the family Hominidae (Homo – humans, Pan – chimpanzees and bonobos, Gorilla, and Pongo – orangutans), and the four genera in the family Hylobatidae or gibbons (Hylobates, Hoolock, Nomascus and Symphalangus). (The genus for the hoolock gibbons was recently changed from Bunopithecus to Hoolock.)

In 1758, Carolus Linnaeus, relying on second- or third-hand accounts, placed a second species in Homo along with H. sapiens: Homo troglodytes ("cave-dwelling man"). It is not clear to which animal this name refers, as Linnaeus had no specimen to refer to, hence no precise description. Linnaeus named the orangutan Simia satyrus ("satyr monkey"). He placed the three genera Homo, Simia and Lemur in the order of Primates.

The troglodytes name was used for the chimpanzee by Blumenbach in 1775 but moved to the genus Simia. The orangutan was moved to the genus Pongo in 1799 by Lacépède.

Linnaeus's inclusion of humans in the primates with monkeys and apes was troubling for people who denied a close relationship between humans and the rest of the animal kingdom. Linnaeus's Lutheran archbishop had accused him of "impiety." In a letter to Johann Georg Gmelin dated 25 February 1747, Linnaeus wrote:

- It is not pleasing to me that I must place humans among the primates, but man is intimately familiar with himself. Let's not quibble over words. It will be the same to me whatever name is applied. But I desperately seek from you and from the whole world a general difference between men and simians from the principles of Natural History. I certainly know of none. If only someone might tell me one! If I called man a simian or vice versa I would bring together all the theologians against me. Perhaps I ought to, in accordance with the law of Natural History.

Accordingly, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in the first edition of his Manual of Natural History (1779), proposed that the primates be divided into the Quadrumana (four-handed, i.e. apes and monkeys) and Bimana (two-handed, i.e. humans). This distinction was taken up by other naturalists, most notably Georges Cuvier. Some elevated the distinction to the level of order.

However, the many affinities between humans and other primates — and especially the "great apes" — made it clear that the distinction made no scientific sense. Charles Darwin wrote, in The Descent of Man:

- The greater number of naturalists who have taken into consideration the whole structure of man, including his mental faculties, have followed Blumenbach and Cuvier, and have placed man in a separate Order, under the title of the Bimana, and therefore on an equality with the orders of the Quadrumana, Carnivora, etc. Recently many of our best naturalists have recurred to the view first propounded by Linnaeus, so remarkable for his sagacity, and have placed man in the same Order with the Quadrumana, under the title of the Primates. The justice of this conclusion will be admitted: for in the first place, we must bear in mind the comparative insignificance for classification of the great development of the brain in man, and that the strongly marked differences between the skulls of man and the Quadrumana (lately insisted upon by Bischoff, Aeby, and others) apparently follow from their differently developed brains. In the second place, we must remember that nearly all the other and more important differences between man and the Quadrumana are manifestly adaptive in their nature, and relate chiefly to the erect position of man; such as the structure of his hand, foot, and pelvis, the curvature of his spine, and the position of his head.

Changes in taxonomy

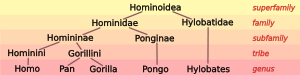

| Until about 1960, the hominoids were usually divided into two families: humans and their extinct relatives in Hominidae, all other hominoids in Pongidae. |  |

| The 1960s saw the application of techniques from molecular biology to primate taxonomy. Goodman used his 1964 immunological study of serum proteins to propose a division of the hominoids into three families, with the "great apes" in Pongidae and the "lesser apes" (gibbons) in Hylobatidae. The trichotomy of hominoid families, however, prompted scientists to ask which family speciated first from the common hominoid ancestor. |  |

| Within the superfamily Hominoidea, gibbons are the outgroup: this means that the rest of the hominoids are more closely related to each other than any of them are to gibbons. This led to the placing of the "great apes" into the family Hominidae along with humans, by demoting the Pongidae to a subfamily; the Hominidae family now contained the subfamilies Homininae and Ponginae. Again, the three-way split in Ponginae led scientists to ask which of the three genera is least related to the others. |  |

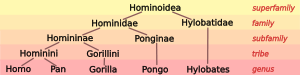

| Investigation showed orangutans to be the outgroup, but comparing humans to all three other hominid genera showed that African "apes" (chimpanzees and gorillas) and humans are more closely related to each other than any of them are to orangutans. This led to the placing of the African hominoids in the subfamily Homininae, forming another three-way split. This classification was first proposed by M. Goodman in 1974. |  |

| To try to resolve the hominine trichotomy, some authors proposed the division of the subfamily Homininae into the tribes Gorillini (African "apes") and Hominini (humans). |  |

| However, DNA comparisons provide convincing evidence that within the subfamily Homininae, gorillas are the outgroup. This suggests that chimpanzees should be in Hominini along with humans. This classification was first proposed (though one rank lower) by M. Goodman et al. in 1990. See Human evolutionary genetics for more information on the speciation of humans and "great apes". |  |

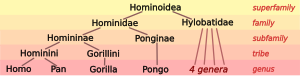

| Later DNA comparisons split the gibbon genus Hylobates into four genera: Hylobates, Hoolock, Nomascus, and Symphalangus. |  |

Classification and evolution

As discussed above, hominoid taxonomy has undergone several changes. Genetic analysis shows that hominoids diverged from the Old World monkeys between 29 million and 34.5 million years ago. The gibbons split from the rest about 18 mya, and the hominid splits happened 14 mya (Pongo), 7 mya (Gorilla), and 3-5 mya (Homo & Pan).

The families, genera and extant species of hominoids are:

- Superfamily Hominoidea

- Family Hylobatidae: gibbons ("lesser apes")

- Genus Hylobates

- Lar gibbon or white-handed gibbon, H. lar

- Bornean white-bearded gibbon, H. albibarbis

- Agile gibbon or black-handed gibbon, H. agilis

- Müller's Bornean gibbon or grey gibbon, H. muelleri

- Silvery gibbon, H. moloch

- Pileated gibbon or capped gibbon, H. pileatus

- Kloss's gibbon or Mentawai gibbon or bilou, H. klossii

- Genus Hoolock

- Western hoolock gibbon, H. hoolock

- Eastern hoolock gibbon, H. leuconedys

- Genus Symphalangus

- Siamang, S. syndactylus

- Genus Nomascus

- Black crested gibbon, N. concolor

- Eastern black crested gibbon, N. nasutus

- Hainan black crested gibbon, N. hainanus

- Southern white-cheeked gibbon N. siki

- White-cheeked crested gibbon, N. leucogenys

- Yellow-cheeked gibbon, N. gabriellae

- Genus Hylobates

- Family Hominidae: hominids ("great apes", including humans)

- Genus Pongo: orangutans

- Bornean orangutan, P. pygmaeus

- Sumatran orangutan, P. abelii

- Genus Gorilla: gorillas

- Western gorilla, G. gorilla

- Eastern gorilla, G. beringei

- Genus Homo: humans

- Human, H. sapiens

- Genus Pan: chimpanzees

- Common chimpanzee, P. troglodytes

- Bonobo, P. paniscus

- Genus Pongo: orangutans

- Family †Parapithecidae

- Genus †Apidium

- Genus †Arsinoea

- Genus †Biretia

- Genus †Parapithecus

- Genus †Qatrania

- Family Hylobatidae: gibbons ("lesser apes")

Cultural aspects of apes

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Often, "apes" (nonhuman hominoids) are said to be the result of a curse—a Jewish folktale claims that one of the races who built the Tower of Babel became apes as punishment, while Muslim lore says that the Jews of Eilat became apes as punishment for fishing on the Sabbath. Some sects of Christianity have folklore that claims that these apes are a symbol of lust and were created by Satan in response to God's creation of humans. It is uncertain whether any of these references are to any specific apes. All of these concepts date from a period when neither the distinction between apes and monkeys, nor the fact that humans are closely related to chimpanzees, was widely understood, if understood at all.

See also

- Chimp Haven

- Declaration on Great Apes from the Great Ape Project

- Human

- List of human evolution fossils

- List of apes (for notable non-fictional apes)

- List of fictional apes

Notes and references

- ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 178–184. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ M. Goodman, D. A. Tagle, D. H. Fitch, W. Bailey, J. Czelusniak, B. F. Koop, P. Benson, J. L. Slightom (1990). "Primate evolution at the DNA level and a classification of hominoids". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 30 (3): 260–266. doi:10.1007/BF02099995. PMID 2109087.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dixson, A.F. (1981), The Natural History of the Gorilla, London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, ISBN 978-0-297-77895-0, p. 13

- Although Dawkins is clear that he uses "apes" for Hominoidea, he also uses "great apes" in ways which exclude humans. Thus in Dawkins, R. (2005), The Ancestor's Tale (p/b ed.), London: Phoenix (Orion Books), ISBN 978-0-7538-1996-8: "Long before people thought in terms of evolution ... great apes were often confused with humans" (p. 114); "gibbons are faithfully monogamous, unlike the great apes which are our closer relatives" (p. 126).

- Grehan, J.R. (2006), "Mona Lisa Smile: The morphological enigma of human and great ape evolution", Anatomical Record, 289B: 139–157

- ^ Benton, Michael J. (2005), Vertebrate palaeontology, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-632-05637-8, retrieved 10 July 2011, p. 371

- ^ Anon. (1911), "Ape", Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. XIX (11th ed.), New York: Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved 10 July 2011

- Dawkins 2005; for example "ll apes except humans are hairy" (p. 99), "mong the apes, gibbons are second only to humans" (p. 126).

- Definitions of paraphyly vary; for the one used here see e.g. Stace, Clive A. (2010a), "Classification by molecules: What's in it for field botanists?" (PDF), Watsonia, 28: 103–122, retrieved 7 February 2010, p. 106

- Dixson 1981, p. 16

- Definitions of monophyly vary; for the one used here see e.g. Mishler, Brent D (2009), "Species are not Uniquely Real Biological Entities", in Ayala, F.J.; Arp, R. (eds.), Contemporary Debates in Philosophy of Biology, pp. 110–122, doi:10.1002/9781444314922.ch6, ISBN 978-1-4443-1492-2

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help), p. 114 - William McGrew (1992). Chimpanzee material culture: implications for human evolution.

- The gestural communication of apes and monkeys: Josep Call, Michael Tomasello - 2007

- ^ Mootnick, A. (2005). "A new generic name for the hoolock gibbon (Hylobatidae)". International Journal of Primatology. 26 (26): 971–976. doi:10.1007/s10764-005-5332-4.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Letter, Carl Linnaeus to Johann Georg Gmelin. Uppsala, Sweden, 25 February 1747". Swedish Linnaean Society.

- Charles Darwin (1871). The Descent of Man. ISBN 0760778140.

- G. G. Simpson (1945). "The principles of classification and a classification of mammals". Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 85: 1–350.

- M. Goodman (1964). "Man's place in the phylogeny of the primates as reflected in serum proteins". In S. L. Washburn (ed.). Classification and human evolution. Aldine, Chicago. pp. 204–234.

- M. Goodman (1974). "Biochemical Evidence on Hominid Phylogeny". Annual Review of Anthropology. 3 (1): 203–228. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.03.100174.001223.

- "Apes, Monkeys Split Earlier Than Fossils Had Indicated/".

External links

- Pilbeam D (2000). "Hominoid systematics: The soft evidence". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (20): 10684–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.210390497. PMC 34045. PMID 10995486.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Agreement between cladograms based on molecular and anatomical data.

| Apes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Extant ape species |

| |

| Study of apes | ||

| Legal and social status | ||

| Related |

| |

Categories: