This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 91.150.222.61 (talk) at 11:06, 9 April 2012. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 11:06, 9 April 2012 by 91.150.222.61 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Blue Army (disambiguation).

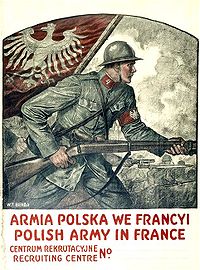

The Blue Army (Polish: Błękitna Armia), or Haller's Army, was the Polish army formed in France in the latter stages of World War I. The names come from the troops' French blue uniforms and the army's commander, General Józef Haller de Hallenburg.

The army was created in June 1917 as part of Polish units allied with the Entente. After the Great War, the army was transferred to Poland, where it took part in renascent Poland's eastern conflicts. During the Polish-Ukrainian War, the Blue Army helped break the stalemate in Poland's favor. During the Polish-Bolshevik War, the Blue Army played a critical role in Poland's successful defense against Soviet forces.

History

Western Front

The first units were formed after the signing of a 1917 alliance by French President Raymond Poincaré and the Polish statesman Ignacy Jan Paderewski. A majority of recruits were either Poles serving in the French army, or former prisoners of war from the German and Austro-Hungarian imperial armies (approximately 35,000 men). An additional 23,000 were Polish Americans. Other Poles flocked to the army from all over the world as well — these units included recruits from the former Russian Expeditionary Force in France and the Polish diaspora in Brazil (more than 300 men).

The army was initially under French political control and under the military command of General Louis Archinard. However, on February 23, 1918, political sovereignty was granted to the Polish National Committee and soon other Polish units were formed, most notably the 4th and 5th Rifle Divisions in Russia. On September 28 Russia formally signed an agreement with the Entente that accepted the Polish units in France as the only, independent, allied and co-belligerent Polish army. On October 4, 1918 the National Committee appointed General Józef Haller de Hallenburg as overall commander.

The first unit to enter combat on the Western Front was the 1st Rifle Regiment (1 pułk strzelców), fighting from July 1918 in Champagne and the Vosges mountains. By October the entire 1st Rifle Division joined the fight in the area of Rambervillers and Raon-l'Étape.

Transfer to Poland

The army continued to gather new recruits after the end of The Great War on November 11, 1918, many of them ethnic Poles who had been conscripted into the Austrian army and later taken prisoners by the Allies. By early 1919 it numbered 68,500 men, fully equipped by the French government. After being denied permission by the German government to enter Poland via the Baltic port city of Danzig (Gdańsk), transport was arranged via train. Between April and June of that year the units were transported together intact to a reborn Poland across Germany in sealed train cars. Weapons were secured in separate cars and kept under guard to appease German concerns about a foreign army traversing its territory. Immediately after its arrival the divisions were integrated into the overall Polish Army and transported to the fronts of the Polish-Ukrainian War, then being fought over control of eastern Galicia.

The perilous journey from France, through revolutionary Germany, into Poland, in the spring of 1919 has been documented by those who lived through it:

Captain Stanislaw I. Nastal

Preparations for the departure lasted for some time. The question of transit became a difficult and complicated problem. Finally after a long wait a decision was made and officially agreed upon between the Allies and Germany.

The first transports with the Blue Army set out in the first half of April 1919. Train after train tore along though Germany to the homeland, to Poland.

Major Stefan Wyczolkowski

On 15 April 1919 the regiment began its trip to Poland from the Bayon railroad station in four transports, via Mainz, Erfurt, Leipzig, Kalisz, and Warsaw, and arrived in Poland, where it was quartered in individual battalions;, in Chelm 1st Battalion, supernumerary company and command of the regiment; 3rd Battalion in Kowel; and the 2nd Battalion in Wlodzimierz.

Major Stanislaw Bobrowski

On 13 April 1919 the regiment set out across Germany for Poland, to reinforce other units of the Polish army being created in the homeland amid battle, shielding with their youthful breasts the resurrected Poland.

Major Jerzy Dabrowski

Finally on 18 April 1919 the regiment’s first transport set out for Poland. On 23 April 1919 the leading divisions of the 3rd Regiment of Polish Riflemen set foot on Polish soil, now free thanks to their own efforts.

Lt. Wincenty Skarzynski

Weeks passed. April 1919 arrived – then plans were changed: it was decided irrevocably to transport our army to Gdansk instead by trains, through Germany. Many officers came from Poland, among them Major Gorecki, to coordinate technical details with General Haller.

After World War I

.

Haller's Army changed the balance of power in Galicia and in Volhynia, and its arrival allowed the Poles to repel the Ukrainians and establish a demarcation line at the river Zbruch. on May 14, 1919. Haller's army was well equipped by the Western allies and partially staffed with experienced French officers specifically in order to fight against the Bolsheviks and not the forces of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic. Despite this obligation, the Poles dispatched Haller's army against the Ukrainians rather than the Bolsheviks in order to break the stalemate in eastern Galicia. The allies sent several telegrams ordering the Poles to halt their offensive as using of the French-equipped army against the Ukrainian specifically contradicted the conditions of the French help, but these were ignored with Poles claiming that "all Ukrainians were Bolsheviks or something close to it".

In July 1919 the Army was transferred to the border with Germany in Silesia, where it prepared defences against any possible German invasion.

Haller's well trained and highly motivated troops, as well as their airplanes and excellent FT-17 tanks, formed part of the core of the Polish forces during the ensuing Polish-Bolshevik War.

Postwar

After the war, the Polish-American volunteers who served within Haller's Army were not recognized as veterans by either the American or Polish governments. This led to friction between the Polish community in the United States and the Polish government, and subsequent refusal by Polish Americans to again help the Polish cause militarily.

The 15th Infantry Rifle Regiment of the Blue Army was the basis for the 49th Hutsul Rifle Regiment of the 11th Infantry Division (Poland)

As with most of the history related to the Polish-Soviet War, information on the Blue Army was censored, distorted and repressed by the Soviet Union during its communist oppression of the 1945-1989 People's Republic of Poland.

Controversies

Although the Blue Army is highly regarded by the Poles; many Ukrainians and Jews generally see it's actions in a negative light.

After their arrival in Western Ukraine, some of Haller's troops were accused of acts of violence against the the local Ukrainian and Jewish populations. As a result of such actions, many Jews perceived Haller's Army as particularly harmful. As the army traveled further East, Haller's soldiers were alleged to loot civilian houses, pushed local Jews off moving trains, and with their bayonets cut off the beards of Orthodox Jews. The latter act was referred to by Haller's soldiers as "civilizing" the Jews. Among the worst offenders within Haller's army were the 23,000 Polish-American volunteers, who were relatively late in joining the unit, and thus poorly disciplined. Those officers and soldiers from the Blue Army who targeted the local Jews believed that they were acting in Poland's defence, because they assumed that the victims were collaborating with Poland's enemies, either West Ukrainian forces, Bolsheviks, or Lithuanians even though many of the civilians killed were not hostile to the Polish military in any way.

In an effort to curb the abuses, Haller himself issued a proclamation demanding that his soldiers cease cutting off beards of elderly Orthodox Jews, and complained about the violent antisemitism of the Polish-American soldiers to an American envoy. Polish government officials, supported by their French allies, noted that German government sources published antisemitic tracts and falsely attributed them to Haller's army in order to weaken Polish claims in eastern Europe. Polish sources furthermore claimed that the many Jews were grateful that the Poles had liberated them from the Ukrainians who were themselves very hostile to the local Jewish populations.

Despite examples of antisemitic behavior exhibited by some troops within the ranks of the Blue Army, many Polish Jews enlisted and fought within its ranks, some even received a commission and were entrusted with leadership positions. Jews serving in the Blue Army's 43rd Regiment of Eastern Frontier Riflemen were listed as combat fatalities, and historian Edward Goldstein identified approximately 5% of the unit's battle casualties as being Jewish.

From the Ukrainian perspective the army's arrival was a significant factor that that led to the eventual demise of the independent West Ukrainian People's Republic, and it's ultimate incorporation into the new Polish state.

Order of battle

- I Polish Corps

- 1st Rifle Division

- 2nd Rifle Division

- 1st Heavy Artillery Regiment

- II Polish Corps - formed in Russia

- III Polish Corps

- 3rd Rifle Division

- 6th Rifle Division

- 3rd Heavy Artillery Regiment

- Independent Units

- 7th Rifle Division

- Training Division - cadre

- 1st Tank Regiment

See also

Bibliography

- Paul Valasek, Haller's Polish Army in France, Chicago, 2006

References

- The Blue Division, Stanislaw I. Nastal, Polish Army Veteran’s Association in America, Cleveland, Ohio 1922

- Outline of the Wartime History of the 43rd regiment of the Eastern Frontier Riflemen, Major Stefan Wyczolkowski, Warsaw 1928

- Outline of the Wartime History of the 44th Regiment of Eastern Frontier Riflemen, Major Stanislaw Bobrowski, Warsaw 1929

- Outline of the Wartime History of the 45th Regiment of Eastern Frontier Infantry Riflemen, Major Jerzy Dabrowski, Warsaw 1928

- The Polish Army in France in Light of the Facts, Wincenty Skarzynski, Warsaw 1929

- Watt, R. (1979). Bitter Glory: Poland and its fate 1918-1939. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Subtelny, op. cit., p. 370

- Martin Conway, José Gotovitch. (2001).Europe in exile: European exile communities in Britain, 1940-1945. Berghahn Books pg. 191

- Antony Polonsky. (1990). My brother's keeper?: recent Polish debates on the Holocaust. Institute for Polish-Jewish Studies: Oxford, England. pg. 100.

- ^ Carole Fink. (2006).Defending the Rights of Others: The Great Powers, the Jews, and International Minority Protection, 1878-1938. Cambridge University Press, pg. 227

- ^ Pavel Korzec. (1993). Polish-Jewish Relations During World War I. In Hostages of modernization: studies on modern antisemitism, 1870-1933/39, Volume 2 Herbert Strauss, Ed. Walter de Gruyter: pp.1034-1035

- ^ Heiko Haumann. (2002). A history of East European Jews Central European University Press, pg. 215

- Justyna Wozniakowska. (2002). Master's Thesis, Central European University Nationalism Studios Program CONFRONTING HISTORY, RESHAPING MEMORY: THE DEBATE ABOUT JEDWABNE IN THE POLISH PRESS pg. 22

- Joanna B. Michlic. (2006). Poland's threatening other: the image of the Jew from 1880 to the present . University of Nebraska Press, pg. 117

- Feigue Cieplinski. Poles and Jews: The Quest For Self-Determination 1919-1934. Binghampton Journal of History, University of Binghamptom. "The Polish Army, dressed proudly in blue uniforms, also dubbed “Hallerczy Boys” because of the name of its captain, fought valiantly and enlarged Polish territory. Josef Haller, an Austrian by birth and trained in France, had been allowed to form there the Polish army in exile and transfer it to Poland. However, Haller had also augmented his troops along the way with badly trained volunteers. Either by design or accident of war, the “Hallerczy Boys” had killed Jews not involved in the direct hostilities during these maneuvers; their neutrality was to no avail as many were accused of having sided with either the Russian or the Ukranians"

- American Jewish Committee.(1920). American Jewish year book, Volume 22 . Jewish Publication Society of America pg. 250

- Andrzej Kapiszewski. (2004). CONTROVERSIAL REPORTS ON THE SITUATION OF JEWS IN POLAND IN THE AFTERMATH OF WORLD WAR I: THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THE US AMBASSADOR IN WARSAW HUGH GIBSON AND AMERICAN JEWISH LEADERS pg. 276

- ^ Goldstein, Edward. Jews in Haller's Army. The Galitzianer, the quarterly journal of Gesher Galicia, May 2002. Goldstein states: "Based on the evidence I have considered I conclude that: (1) individual Hallerczyki and probably units of Haller’s Army committed anti-Semitic atrocities while in Poland, and (2) thousands of Jews served in Haller’s Army. Cite error: The named reference "Goldstein" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "communities1" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "google" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "google2" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "google3" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "kluszczynski" is not used in the content (see the help page).

External links

- Haller Army Website

- Józef Haller and the Blue Army

- THE POLISH ARMY IN FRANCE: IMMIGRANTS IN AMERICA, WORLD WAR I VOLUNTEERS IN FRANCE, DEFENDERS OF THE RECREATED STATE IN POLAND by DAVID T. RUSKOSKI