This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Joe Decker (talk | contribs) at 16:34, 28 February 2013 (rm interwiki (redirect case)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:34, 28 February 2013 by Joe Decker (talk | contribs) (rm interwiki (redirect case))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| A joint Politics and Economics series |

| Social choice and electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

Single-winner methodsSingle vote - plurality methods

|

|

Proportional representationParty-list

|

|

Mixed systemsBy results of combination

By mechanism of combination By ballot type |

|

Paradoxes and pathologiesSpoiler effects

Pathological response Paradoxes of majority rule |

Social and collective choiceImpossibility theorems

Positive results |

|

|

A first-past-the-post (abbreviated FPTP or FPP) election is one that is won by the candidate with more votes than any other(s). It is a common, but not universal, feature of electoral systems with single-member legislative districts, and generally results over time with a two-party competition.

Overview

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "First-past-the-post voting" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The first-past-the-post voting method is one of several plurality voting systems. It is also known as the 'winner-takes-all', or 'simple plurality'.

Confusion in terminology often exists between highest vote, majority vote and plurality voting systems. All three use a first-past-the-post voting method, but there are subtle differences in the method of execution. First-past-the-post voting is also used in two-round systems and exhaustive ballots.

First-past-the-post voting methods can be used for single and multiple member elections. In a single member election the candidate with the highest number, not necessarily a majority, of votes is elected. The two-round ('runoff') voting system uses a first-past-the-post voting method in each of the two rounds. The first round determines which two candidates will progress to the second, final round ballot.

In a multiple member first-past-the-post ballot, the first number of candidates, in order of highest vote, corresponding to the number of positions to be filled are elected. If there are six vacancies then the first six candidates with the highest vote are elected. A multiple selection ballot where more than one candidate can be voted for is also a form of first-past-the-post voting in which voters are allowed to cast a vote for as many candidates as there are vacant positions; the candidate(s) with the highest number of votes is elected.

The Electoral Reform Society is a political pressure group based in the United Kingdom which advocates scrapping First Past the Post (FPTP) for all National and local elections. It argues FPTP is 'bad for voters, bad for government and bad for democracy'. It is the oldest organisation concerned with electoral systems in the world.

All U.S. States – other than Maine and Nebraska – as of 2008 use a winner-take-all form of simple plurality, first-past-the-post voting to determine the electors appointed to the Electoral College. Under the typical system, the candidate that gains the highest vote total wins all of the state's available electors.

Example

Template:Singaporean presidential election, 2011

Under a first-past-the-post voting system the highest polling candidate (or a group of candidates for some cases) is elected. In this real-life example, Tony Tan obtained a greater number than the other candidates, and so was declared the winner.

Effects

The effect of a system based on single seat constituencies is that the larger parties gain a disproportionately large share of seats, while smaller parties are left with a disproportionately small share of seats. For example, the 2005 UK General election results in Great Britain were as follows:

| Seats This table indicates those parties with over one seat, Great Britain only |

Seats % | Votes % | Votes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labour Party | 355 | 56.5 | 36.1 | 9,552,436 |

| Conservative Party | 198 | 31.5 | 33.2 | 8,782,192 |

| Liberal Democrats | 62 | 9.9 | 22.6 | 5,985,454 |

| Scottish National Party | 6 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 412,267 |

| Plaid Cymru | 3 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 174,838 |

| Others | 4 | 0.6 | 5.7 | 1,523,716 |

| 628 | 26,430,908 | |||

It can be seen that Labour took a majority of seats, 57%, with only 36% of the vote. The largest two parties took 69% of votes and 88% of seats. Meanwhile, the smaller Liberal Democrat party took over a fifth of votes but only about a tenth of the seats in parliament.

Criticisms

Tactical voting

Main article: Comparison of instant runoff voting to other voting systemsTo a greater extent than many other electoral methods, the first-past-the-post system encourages tactical voting. Voters have an incentive to vote for one of the two candidates they predict are most likely to win, even if they would prefer another of the candidates to win, because a vote for any other candidate will likely be "wasted" and have no impact on the final result.

The position is sometimes summed up, in an extreme form, as "All votes for anyone other than the second place are votes for the winner", because by voting for other candidates, they have denied those votes to the second place candidate who could have won had they received them. Following the 2000 U.S. presidential election, some supporters of Democratic candidate Al Gore believed he lost the extremely close election to Republican George W. Bush because a portion of the electorate (2.7%) voted for Ralph Nader of the Green Party, and exit polls indicated that more of these voters would have preferred Gore (45%) to Bush (27%), with the rest not voting in Nader's absence.

In Puerto Rico, there are three principal voter groups: the Independentistas (pro-independence), the Populares (pro-commonwealth), and the Estadistas (pro-statehood). Historically, there has been a tendency for Independentista voters to elect Popular candidates and policies. This phenomenon is responsible for some Popular victories, even though the Estadistas have the most voters on the island. It is so widely recognised that the Puerto Ricans sometimes call the Independentistas who vote for the Populares "melons", because the fruit is green on the outside but red on the inside (in reference to the party colors).

Because voters have to predict in advance who the top two candidates will be, results can be significantly distorted:

- Substantial power is given to the media. Some voters will tend to believe the media's assertions as to who the leading contenders are likely to be in the election. Even voters who distrust the media will know that other voters do believe the media, and therefore that those candidates who receive the most media attention will probably be the most popular and thus most likely to be the top two.

- A new candidate with no track record, who might otherwise be supported by the majority of voters, may be considered unlikely to be one of the top two candidates; thus they will receive fewer votes, which will then give them a reputation as a low poller in future elections, perpetuating the position.

- The system may promote votes against as opposed to votes for. In the UK, entire campaigns have been organised with the aim of voting against the Conservative party by voting either Labour or Liberal Democrat. For example, in a constituency held by the Conservatives, with the Liberal Democrats as the second-place party and the Labour Party in third, Labour supporters might be urged to vote for the Liberal Democrat candidate (who has a smaller shortfall of votes to make up and more support in the constituency) rather than their own candidate, on the basis that Labour supporters would prefer an MP from a competing left/liberal party to a Conservative one.

- If enough voters use this tactic, the first-past-the-post system effectively becomes runoff voting - a completely different system - in which the first round is held in the court of public opinion. A good example of this is believed to be the Winchester by-election, 1997.

Proponents of other single-winner voting systems argue that their proposals would reduce the need for tactical voting and reduce the spoiler effect. Examples include the commonly used two-round system of runoffs and instant runoff voting, along with less tested systems such as approval voting and Condorcet methods.

Effect on political parties

Duverger's law is an idea in political science which says that constituencies that use first-past-the-post systems will become two-party systems, given enough time. Economist Jeffrey Sachs explains:

The main reason for America's majoritarian character is the electoral system for Congress. Members of Congress are elected in single-member districts according to the "first-past-the-post" (FPTP) principle, meaning that the candidate with the plurality of votes is the winner of the congressional seat. The losing party or parties win no representation at all. The first-past-the-post election tends to produce a small number of major parties, perhaps just two, a principle known in political science as Duverger's Law. Smaller parties are trampled in first-past-the-post elections.

— from Sachs' The Price of Civilization, 2011

First-past-the-post tends to reduce the number of viable political parties to a greater extent than most other methods, thus making it more likely that a single party will hold a majority of legislative seats. (In the United Kingdom, 18 out of 23 general elections since 1922 have produced a single party majority government.)

FPTP's tendency toward fewer parties and more frequent one-party rule can potentially produce a government that may not consider as wide a range of perspectives and concerns. It is entirely possible that a voter will find that all major parties agree on a particular issue. In this case, the voter will not have any meaningful way of expressing a dissenting opinion through his or her vote.

As fewer choices are offered to the voters, voters may vote for a candidate with whom they largely disagree so as to oppose a candidate with whom they disagree even more (See tactical voting above). The downside of this is that candidates will less closely reflect the viewpoints of those who vote for them.

It may also be argued that one-party rule is more likely to lead to radical changes in government policy that are only favoured by a plurality or bare majority of the voters, whereas multi-party systems usually require greater consensus in order to make dramatic changes.

Wasted votes

Wasted votes are votes cast for losing candidates or votes cast for winning candidates in excess of the number required for victory. For example, in the UK General Election of 2005, 52% of votes were cast for losing candidates and 18% were excess votes - a total of 70% wasted votes. This is perhaps the most fundamental criticism of FPTP, that a large majority of votes may play no part in determining the outcome. This "winner-takes-all" system may be one of the reasons why "voter participation tends to be lower in countries with FPTP than elsewhere."

Gerrymandering

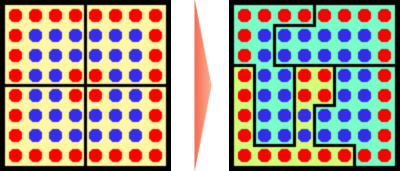

Because FPTP permits many wasted votes, an election under FPTP is easily gerrymandered. Through gerrymandering, constituencies are deliberately designed to unfairly increase the number of seats won by one party at the expense of another.

For example, suppose that governing Blue-dot party wishes to reduce the seats that will be won by opposition Red-dot party in the next election. It creates a number of constituencies in each of which the Red-dot party has an overwhelming majority of votes (such as the district in the lower left hand corner.) The Red-dot party will win these seats, but a large number of its voters will waste their votes. Then the rest of the constituencies are designed with small majorities for the Blue-dot party. Few Blue-dot votes are wasted, and the Blue-dot party will win a large number of seats by small margins. As a result of the gerrymander, the Red-dot party's seats have cost it more votes than the Blue-dot party's seats. In the diagram, after the gerrymander, the Blue-dot party will win three seats and the Red-dot party only one seat, despite the existence of an equal number of voters overall for both parties.

Manipulation charges

The presence of spoilers often gives rise to suspicions that manipulation of the slate has taken place. The spoiler may have received incentives to run. A spoiler may also drop out at the last moment, inducing charges that such an act was intended from the beginning.

Disproportionate influence of smaller parties

Smaller parties can disproportionately change the outcome of an FPTP election by swinging what is called the 50-50% balance of two party systems, by creating a faction within one or both ends of the political spectrum which shifts the winner of the election from an absolute majority outcome to a simple majority outcome favouring the previously less favoured party. In comparison, for electoral systems using proportional representation small groups win only their proportional share of representation. However in PR systems, small parties can become decisive in Parliament so gaining a power of blackmail against the Government, a problem which is generally reduced by the FPTP system.

Voting system criteria

Main article: Comparison of instant runoff voting to other voting systems § Voting system criteriaScholars rate voting systems using mathematically-derived voting system criteria, which describe desirable features of a system. No ranked preference method can meet all of the criteria, because some of them are mutually exclusive, as shown by statements such as Arrow's impossibility theorem and the Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem.

Majority criterion

![]() Y The majority criterion states that "if one candidate is preferred by a majority (more than 50%) of voters, then that candidate must win". First-past-the-post meets this criterion (though not the converse: a candidate does not need 50% of the votes in order to win). Although the criterion is met for each constituency vote, it is not met when adding up the total votes for a winning party in a parliament.

Y The majority criterion states that "if one candidate is preferred by a majority (more than 50%) of voters, then that candidate must win". First-past-the-post meets this criterion (though not the converse: a candidate does not need 50% of the votes in order to win). Although the criterion is met for each constituency vote, it is not met when adding up the total votes for a winning party in a parliament.

Condorcet winner criterion

![]() N The Condorcet winner criterion states that "if a candidate would win a head-to-head competition against every other candidate, then that candidate must win the overall election". First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

N The Condorcet winner criterion states that "if a candidate would win a head-to-head competition against every other candidate, then that candidate must win the overall election". First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

Condorcet loser criterion

![]() N The Condorcet loser criterion states that "if a candidate would lose a head-to-head competition against every other candidate, then that candidate must not win the overall election". First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

N The Condorcet loser criterion states that "if a candidate would lose a head-to-head competition against every other candidate, then that candidate must not win the overall election". First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

Independence of irrelevant alternatives criterion

![]() N The independence of irrelevant alternatives criterion states that "the election outcome remains the same even if a candidate who cannot win decides to run." First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

N The independence of irrelevant alternatives criterion states that "the election outcome remains the same even if a candidate who cannot win decides to run." First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

Independence of clones criterion

![]() N The independence of clones criterion states that "the election outcome remains the same even if an identical candidate who is equally-preferred decides to run." First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

N The independence of clones criterion states that "the election outcome remains the same even if an identical candidate who is equally-preferred decides to run." First-past-the-post does not meet this criterion.

See also

- Cube rule

- Deviation from proportionality

- Plurality-at-large voting

- Single non-transferable vote

- Single transferable vote

References

- Rosenbaum, David E. (24 February 2004). "THE 2004 CAMPAIGN: THE INDEPENDENT; Relax, Nader Advises Alarmed Democrats, but the 2000 Math Counsels Otherwise". New York Times. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- Sachs, Jeffrey (2011). The Price of Civilization. New York: Random House. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-4000-6841-8.

- Drogus, Carol Ann (2008). Introducing comparative politics: concepts and cases in context. CQ Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-87289-343-6.

- Ilan, Shahar. "about blackmail power of Israeli small parties under PR". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- "Dr.Mihaela Macavei, University of Alba Iulia" (PDF). Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- David Austen-Smith and Jeffrey Banks, "Monotonicity in Electoral Systems," American Political Science Review, Vol 85, No 2 (Jun. 1991)

- Single-winner Voting Method Comparison Chart "Majority Favorite Criterion: If a majority (more than 50%) of voters consider candidate A to be the best choice, then A should win."

- ^ Felsenthal, Dan S. (2010) Review of paradoxes afflicting various voting procedures where one out of m candidates (m ≥ 2) must be elected. In: Assessing Alternative Voting Procedures, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK.

External links

- A handbook of Electoral System Design from International IDEA

- ACE Project: What is the electoral system for Chamber 1 of the national legislature?

- ACE Project: First Past The Post - Detailed explanation of first-past-the-post voting

- ACE Project: Experiments with moving away from FPTP in the UK

- ACE Project: Electing a President using FPTP

- ACE Project: FPTP on a grand scale in India

- The Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform says the new proportional electoral system it proposes for British Columbia will improve the practice of democracy in the province.

- ASSEMBLY AUDIO AND VIDEO Below, you'll find audio and video recordings of six Learning Phase weekends, a meeting held in Prince George and the six Deliberation Phase weekends. The Learning Phase and Deliberation Phase recordings were broadcast on Hansard TV during 2004. - week 5 gives a detailed description by David Farrell, of the University of Manchester (England), Elizabeth McLeay of Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

- The Problem With First-Past-The-Post Electing (data from UK general election 2005)

- The Problems with First Past the Post Voting Explained (video)

| 2011 United Kingdom Alternative Vote referendum | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results | |||||||

| Referendum question | "At present, the UK uses the “first past the post” system to elect MPs to the House of Commons. Should the “alternative vote” system be used instead?" | ||||||

| Legislation | |||||||

| Parties |

| ||||||

| Advocacy groups |

| ||||||

| Print media |

| ||||||

| Politics Portal | |||||||

Categories: