This is an old revision of this page, as edited by OccultZone (talk | contribs) at 15:10, 2 September 2014 (→Background: doubtful image). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

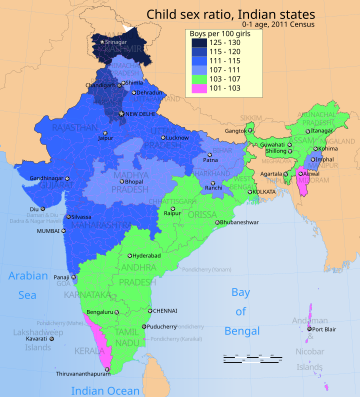

Revision as of 15:10, 2 September 2014 by OccultZone (talk | contribs) (→Background: doubtful image)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Female foeticide is the act of aborting a foetus because it is female. The frequency of female foeticide is indirectly estimated from the observed high birth sex ratio, that is the ratio of boys to girls at birth. The natural ratio is assumed to be between 103 to 107, and any number above it is considered as suggestive of female foeticide. According to the decennial Indian census, the sex ratio in the 0-6 age group in India has risen from 102.4 males per 100 females in 1961, to 104.1 in 1981, to 107.8 in 2001, to 108.8 in 2011. The child sex ratio is within the normal natural range in all eastern and southern states of India, but significantly higher in certain western and particularly northwestern states such as Punjab, Haryana and Jammu & Kashmir (120, 118 and 116, as of 2011, respectively). High birth sex ratio and implied female foeticide is an issue that is not unique to India. Even higher sex ratio than India have been reported for last 20 years in China, Pakistan, Viet Nam, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia and some Southeast European countries. There is an on-going debate as to whether these high sex ratios are only caused by female foeticide or some of the higher ratio is explained by natural causes.

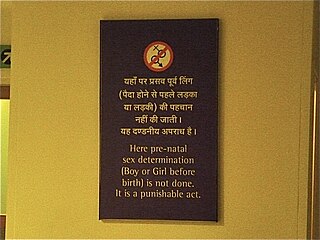

Foetal sex determination and sex-selective abortion has been estimated to be a ₹100 (US$1.20) industry. The Indian government has passed Pre-Conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) (PCPNDT) Act in 2004 to ban and punish prenatal sex screening and female foeticide. It is currently illegal in India to determine or disclose sex of the foetus to anyone. However, there are concerns that PCPNDT Act has been poorly enforced by authorities.

Background

Main article: Human sex ratioIndia is one of the several countries where higher human sex ratio is observed. This is assumed to be caused by female foeticide, an assumption that is the subject of considerable scholarly debate and continuing scientific studies. Human sex ratio is the relative number of males to females in a given age group. The natural human sex ratio at birth was estimated, in a 2002 study, to be close to 106 boys to 100 girls.

Human sex ratio at birth that is significantly different from 106 is often assumed to be correlated to the prevalence and scale of sex-selective abortion. A birth sex ratio impacts a society's overall sex ratio over time, as well the child sex ratio in near term. In India, child sex ratio is defined as the ratio of boys to girls in 0-6 year age group. India's child sex ratio was 108 according to its 2001 census, and 109 according to its 2011 census. The national average masks the variations in regional numbers according to 2011 census — Haryana’s ratio was 120, Punjab’s ratio was 118, Jammu & Kashmir was 116, and Gujarat’s ratio was 111. The 2011 Census found eastern states of India had birth sex ratios between 103 and 104, lower than normal. In contrast to decadal nationwide census data, small non-random sample surveys report higher child sex ratios in India.

The child sex ratio in India shows a regional pattern. India’s 2011 census found that all eastern and southern states of India had a child sex ratio between 103 to 107, typically considered as the “natural ratio.” The highest sex ratios were observed in India's northern and northwestern states - Haryana (120), Punjab (118) and Jammu & Kashmir (116). The western states of Maharashtra and Rajasthan 2011 census found a child sex ratio of 113, Gujarat at 112 and Uttar Pradesh at 111. The Indian census data suggests there is a positive correlation between abnormal sex ratio and better socio-economic status and literacy. Urban India has higher child sex ratio than rural India according to 1991, 2001 and 2011 Census data, implying higher prevalence of female foeticide in urban India. Similarly, child sex ratio greater than 115 boys per 100 girls is found in regions where the predominant majority is Hindu, Muslim, Sikh or Christian; furthermore "normal" child sex ratio of 104 to 106 boys per 100 girls are also found in regions where the predominant majority is Hindu, Muslim, Sikh or Christian. These data contradict any hypotheses that may suggest that sex selection is an archaic practice which takes place among uneducated, poor sections or particular religion of the Indian society.

High sex ratio implies female foeticide

One school of scholars suggest that any birth sex ratio of boys to girls that is outside of the normal 105-107 range, necessarily implies sex-selective abortion. These scholars claim that both the sex ratio at birth and the population sex ratio are remarkably constant in human populations. Significant deviations in birth sex ratios from the normal range can only be explained by manipulation, that is sex-selective abortion. In a widely cited article, Amartya Sen compared the birth sex ratio in Europe (106) and United States (105) with those in Asia (107+) and argued that the high sex ratios in East Asia, West Asia and South Asia may be due to excessive female mortality. Sen pointed to research that had shown that if men and women receive similar nutritional and medical attention and good health care then females have better survival rates, and it is the male which is the genetically fragile sex. Sen estimated 'missing women' from extra women who would have survived in Asia if it had the same ratio of women to men as Europe and United States. According to Sen, the high birth sex ratio over decades, implies a female shortfall of 11% in Asia, or over 100 million women as missing from the 3 billion combined population of India, other South Asian countries, West Asia, North Africa and China.

High human sex ratio may be natural

Other scholars question whether birth sex ratio outside 103-107 can be due to natural reasons. William James and others suggest that conventional assumptions have been:

- there are equal numbers of X and Y chromosomes in mammalian sperms

- X and Y stand equal chance of achieving conception

- therefore equal number of male and female zygotes are formed, and that

- therefore any variation of sex ratio at birth is due to sex selection between conception and birth.

James cautions that available scientific evidence stands against the above assumptions and conclusions. He reports that there is an excess of males at birth in almost all human populations, and the natural sex ratio at birth is usually between 102 to 108. However the ratio may deviate significantly from this range for natural reasons such as early marriage and fertility, teenage mothers, average maternal age at birth, paternal age, age gap between father and mother, late births, ethnicity, social and economic stress, warfare, environmental and harmonal effects. This school of scholars support their alternate hypothesis with historical data when modern sex-selection technologies were unavailable, as well as birth sex ratio in sub-regions, and various ethnic groups of developed economies. They suggest that direct abortion data should be collected and studied, instead of drawing conclusions indirectly from human sex ratio at birth.

James hypothesis is supported by historical birth sex ratio data before technologies for ultrasonographic sex-screening were discovered and commercialized in 1960s and 1970s, as well by reverse abnormal sex ratios currently observed in Africa. Michel Garenne reports that many African nations have, over decades, witnessed birth sex ratios below 100, that is more girls are born than boys. Angola, Botswana and Namibia have reported birth sex ratios between 94 to 99, which is quite different than the presumed 104 to 106 as natural human birth sex ratio. South Korea's historical records suggest a birth sex ratio of 1.13, based on 5 million births, in 1920s over a 10 year period. Other historical records from Asia too support James hypothesis. For example, Jiang et al. claim that the birth sex ratio in China was 116–121 over a 100 year period in late 18th and early 19th century; in the 120–123 range in early 20th century; falling to 112 in the 1930s.

Origin

Female foeticide has been linked to the arrival, in the early 1990s, of affordable ultrasound technology and its widespread adoption in India. Obstetric ultrasonography, either transvaginally or transabdominally, checks for various markers of fetal sex. It can be performed at or after week 12 of pregnancy. At this point, 3⁄4 of fetal sexes can be correctly determined, according to a 2001 study. Accuracy for males is approximately 50% and for females almost 100%. When performed after week 13 of pregnancy, ultrasonography gives an accurate result in almost 100% of cases.

- Availability

Ultrasound technology arrived in China and India in 1979, but its expansion was slower in India. Ultrasound sex discernment technologies were first introduced in major cities of India in 1980s, its use expanded in India's urban regions in 1990s, and became widespread in 2000s.

Magnitude estimates for female foeticide

Estimates for female foeticide vary by scholar. One group estimates more than 10 million female foetuses may have been illegally aborted in India since 1990s, and 500,000 girls were being lost annually due to female foeticide. MacPherson estimates that 100,000 abortions every year continue to be performed in India solely because the fetus is female.

Child sex ratio and foeticide by states of India

The following table presents the child sex ratio data for India's states and union territories, according to 2011 Census of India for population count in the 0-1 age group. The data suggests 18 states/UT had birth sex ratio higher than 107 implying excess males at birth and/or excess female mortalities after birth but before she reaches the age of 1, 13 states/UT had normal child sex ratios in the 0-1 age group, and 4 states/UT had birth sex ratio less than 103 implying excess females at birth and/or excess male mortalities after birth but before he reaches the age of 1.

| State / UT | Boys (0-1 age) 2011 Census |

Girls (0-1 age) 2011 Census |

Sex ratio (Boys per 100 girls) |

|---|---|---|---|

| India | 10,633,298 | 9,677,936 | 109.9 |

| JAMMU & KASHMIR | 154,761 | 120,551 | 128.4 |

| HARYANA | 254,326 | 212,408 | 119.7 |

| PUNJAB | 226,929 | 193,021 | 117.6 |

| UTTARAKHAND | 92,117 | 80,649 | 114.2 |

| DELHI | 135,801 | 118,896 | 114.2 |

| MAHARASHTRA | 946,095 | 829,465 | 114.1 |

| LAKSHADWEEP | 593 | 522 | 114.0 |

| RAJASTHAN | 722,108 | 635,198 | 113.7 |

| GUJARAT | 510,124 | 450,743 | 113.2 |

| UTTAR PRADESH | 1,844,947 | 1,655,612 | 111.4 |

| CHANDIGARH | 8,283 | 7,449 | 111.2 |

| DAMAN & DIU | 1,675 | 1,508 | 111.1 |

| BIHAR | 1,057,050 | 957,907 | 110.3 |

| HIMACHAL PRADESH | 53,261 | 48,574 | 109.6 |

| MADHYA PRADESH | 733,148 | 677,139 | 108.3 |

| GOA | 9,868 | 9,171 | 107.6 |

| JHARKHAND | 323,923 | 301,266 | 107.5 |

| MANIPUR | 22,852 | 21,326 | 107.2 |

| ANDHRA PRADESH | 626,538 | 588,309 | 106.5 |

| TAMIL NADU | 518,251 | 486,720 | 106.5 |

| ODISHA | 345,960 | 324,949 | 106.5 |

| DADRA & NAGAR HAVELI | 3,181 | 3,013 | 105.6 |

| WEST BENGAL | 658,033 | 624,760 | 105.0 |

| KARNATAKA | 478,346 | 455,299 | 105.1 |

| ASSAM | 280,888 | 267,962 | 104.8 |

| NAGALAND | 17,103 | 16,361 | 104.5 |

| SIKKIM | 3,905 | 3,744 | 104.3 |

| CHHATTISGARH | 253,745 | 244,497 | 103.8 |

| TRIPURA | 28,650 | 27,625 | 103.7 |

| MEGHALAYA | 41,353 | 39,940 | 103.5 |

| ARUNACHAL PRADESH | 11,799 | 11,430 | 103.2 |

| ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS | 2,727 | 2,651 | 102.9 |

| KERALA | 243,852 | 238,489 | 102.2 |

| PUDUCHERRY | 9,089 | 8,900 | 102.1 |

| MIZORAM | 12,017 | 11,882 | 101.1 |

Reasons for female foeticide

Various theories have been proposed as possible reasons for sex-selective abortion. Culture is favored by some researchers, while some favor disparate gender-biased access to resources. Some demographers question whether sex-selective abortion or infanticide claims are accurate, because underreporting of female births may also explain high sex ratios. Natural reasons may also explain some of the abnormal sex ratios. Klasen and Wink suggest India and China’s high sex ratios are primarily the result of sex-selective abortion.

Cultural preference

One school of scholars suggest that female foeticide can be seen through history and cultural background. Generally, male babies were preferred because they provided manual labor and success the family lineage. The selective abortion of female fetuses is most common in areas where cultural norms value male children over female children for a variety of social and economic reasons. A son is often preferred as an "asset" since he can earn and support the family; a daughter is a "liability" since she will be married off to another family, and so will not contribute financially to her parents. Female foeticide then, is a continuation in a different form, of a practice of female infanticide or withholding of postnatal health care for girls in certain households. Furthermore, in some cultures sons are expected to take care of their parents in their old age. These factors are complicated by the effect of diseases on child sex ratio, where communicable and noncommunicable diseases affect males and females differently.

Disparate gendered access to resources

Some of the variation in birth sex ratios and implied female foeticide may be due to disparate access to resources. As MacPherson (2007) notes, there can be significant differences in gender violence and access to food, healthcare, immunizations between male and female children. This leads to high infant and childhood mortality among girls, which causes changes in sex ratio.

Disparate, gendered access to resources appears to be strongly linked to socioeconomic status. Specifically, poorer families are sometimes forced to ration food, with daughters typically receiving less priority than sons (Klasen and Wink 2003). However, Klasen’s 2001 study revealed that this practice is less common in the poorest families, but rises dramatically in the slightly less poor families. Klasen and Wink’s 2003 study suggests that this is “related to greater female economic independence and fewer cultural strictures among the poorest sections of the population.” In other words, the poorest families are typically less bound by cultural expectations and norms, and women tend to have more freedom to become family breadwinners out of necessity.

Lopez and Ruzikah (1983) found that, when given the same resources, women tend to outlive men at all stages of life after infancy. However, globally, resources are not always allocated equitably. Thus, some scholars argue that disparities in access to resources such as healthcare, education, and nutrition play at least a small role in the high sex ratios seen in some parts of the world.

Laws and regulations

India passed its first abortion-related law, the so-called Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971, making abortion legal in most states, but specified legally acceptable reasons for abortion such as medical risk to mother and rape. The law also established physicians who can legally provide the procedure and the facilities where abortions can be performed, but did not anticipate female foeticide based on technology advances. With increasing availability of sex screening technologies in India through the 1980s in urban India, and claims of its misuse, the Government of India passed the Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques Act (PNDT) in 1994. This law was further amended into the Pre-Conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) (PCPNDT) Act in 2004 to deter and punish prenatal sex screening and female foeticide. However, there are concerns that PCPNDT Act has been poorly enforced by authorities.

The impact of Indian laws on female foeticide and its enforcement is unclear. United Nations Population Fund and India's National Human Rights Commission, in 2009, asked the Government of India to assess the impact of the law. The Public Health Foundation of India, an activist NGO in its 2010 report, claimed a lack of awareness about the Act in parts of India, inactive role of the Appropriate Authorities, ambiguity among some clinics that offer prenatal care services, and the role of a few medical practitioners in disregarding the law. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of India has targeted education and media advertisements to reach clinics and medical professionals to increase awareness. The Indian Medical Association has undertaken efforts to prevent prenatal sex selection by giving its members Beti Bachao (save the daughter) badges during its meetings and conferences.

According to a 2007 study by MacPherson, prenatal Diagnostic Techniques Act (PCPNDT Act) was highly publicized by NGOs and the government. Many of the ads used depicted abortion as violent, creating fear of abortion itself within the population. The ads focused on the religious and moral shame associated with abortion. MacPherson claims this media campaign was not effective because some perceived this as an attack on their character, leading to many becoming closed off, rather than opening a dialogue about the issue. This emphasis on morality, claims MacPherson, increased fear and shame associated with all abortions, leading to an increase in unsafe abortions in India.

The government of India, in a 2011 report, has begun better educating all stakeholders about its MTP and PCPNDT laws. In its communication campaigns, it is clearing up public misconceptions by emphasizing that sex determination is illegal, but abortion is legal for certain medical conditions in India. The government is also supporting implementation of programs and initiatives that seek to reduce gender discrimination, including media campaign to address the underlying social causes of sex selection.

Other recent policy initiatives adopted by many states of India, claims Guilmoto, attempt to address the assumed economic disadvantage of girls by offering support to girls and their parents. These policies provide conditional cash transfer and scholarships only available to girls, where payments to a girl and her parents are linked to each stage of her life, such as when she is born, completion of her childhood immunization, her joining school at grade 1, her completing school grades 6, 9 and 12, her marriage past age 21. Some states are offering higher pension benefits to parents who raise one or two girls. Different states of India have been experimenting with various innovations in their girl-driven welfare policies. For example, the state of Delhi adopted a pro-girl policy initiative (locally called Laadli scheme), which initial data suggests may be lowering the birth sex ratio in the state.

Response from others

Increasing awareness of the problem has led to multiple campaigns by celebrities and journalists to combat sex-selective abortions. Aamir Khan devoted the first episode "Daughters Are Precious" of his show Satyamev Jayate to raise awareness of this widespread practice, focusing primarily on Western Rajastan, which is known to be one of the areas where this practice is common. Its sex ratio dropped to 883 girls per 1,000 boys in 2011 from 901 girls to 1000 boys in 2001. Rapid response was shown by local government in Rajastan after the airing of this show, showing the effect of media and nationwide awareness on the issue. A vow was made by officials to set up fast-track courts to punish those who practice sex-based abortion. They cancelled the licences of six sonography centres and issued notices to over 20 others.

This has been done on the smaller scale. Cultural intervention has been addressed through theatre. Plays such as 'Pacha Mannu', which is about female infanticide/foeticide, has been produced by a women's theatre group in Tamil Nadu. This play was showing mostly in communities that practice female infanticide/foeticide and has led to a redefinition of a methodology of consciousness raising, opening up varied ways of understanding and subverting cultural expressions.

The Mumbai High Court ruled that prenatal sex determination implied female foeticide. Sex determination violated a woman's right to live and was against India's Constitution.

The Beti Bachao, or Save girls campaign, has been underway in many Indian communities since the early 2000s. The campaign uses the media to raise awareness of the gender disparities creating, and resulting from, sex-selective abortion. Beti Bachao activities include rallies, posters, short videos and television commercials, some of which are sponsored by state and local governments and other organisations. Many celebrities in India have publicly supported the Beti Bachao campaign.

See also

- Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act, 1994

- Domestic violence in India

- Dowry system in India

- Sexism in India

- Sex-selective abortion

- Bride burning

- Foeticide

- Gendercide

- Selective reduction

- Sex selection

- Female infanticide in India

References

- Data Highlights - 2001 Census Census Bureau, Government of India

- ^ India at Glance - Population Census 2011 - Final Census of India, Government of India (2013)

- ^ Child Sex Ratio in India C Chandramouli, Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India (2011)

- ^ Christophe Z Guilmoto, Sex imbalances at birth Trends, consequences and policy implications United Nations Population Fund, Hanoi (October 2011)

- ^ James W.H. (July 2008). "Hypothesis:Evidence that Mammalian Sex Ratios at birth are partially controlled by parental hormonal levels around the time of conception". Journal of Endocrinology. 198 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1677/JOE-07-0446. PMID 18577567.

- ^ "UNICEF India". UNICEF.

- Kumm, J.; Laland, K. N.; Feldman, M. W. (December 1994). "Gene-culture coevolution and sex ratios: the effects of infanticide, sex-selective abortion, sex selection, and sex-biased parental investment on the evolution of sex ratios". Theoretical Population Biology. 43 (3, number 3): 249–278. doi:10.1006/tpbi.1994.1027. PMID 7846643.

- Grech, V; Savona-Ventura, C; Vassallo-Agius, P (2002). "Unexplained differences in sex ratios at birth in Europe and North America". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 324 (7344). BMJ, NCBI/National Institutes of Health: 1010–1. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7344.1010. PMC 102777. PMID 11976243.

- Census of India 2011: Child sex ratio drops to lowest since Independence The Economic Times, India

- Trends in Sex Ratio at Birth and Estimates of Girls Missing at Birth in India UNFPA (July 2010)

- ^ Child Sex Ratio 2001 versus 2011 Census of India, Government of India (2013)

- ^ IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PCPNDT ACT IN INDIA - Perspectives and Challenges Public Health Foundation of India, Supported by United Nations FPA (2010)

- Therese Hesketh and Zhu Wei Xing, Abnormal sex ratios in human populations: Causes and consequences, PNAS, September 5, 2006, vol. 103, no. 36, pp 13271-13275

- ^ Klausen, Stephan and Claudia Wink. "Missing Women: Revisiting the Debate" Feminist Economics 9 (2003): 263-299.

- Sen, Amartya (1990), More than 100 million women are missing, New York Review of Books, 20 December, pp. 61–66

- Kraemer, Sebastian. "The Fragile Male." British Medical Journal (2000): n. pag. British Medical Journal. Web. 20 Oct. 2013.

- see:

- James WH (1987). "The human sex ratio. Part 1: A review of the literature". Human Biology. 59 (5): 721–752. PMID 3319883. Retrieved August 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - James WH (1987). "The human sex ratio. Part 2: A hypothesis and a program of research". Human Biology. 59 (6): 873–900. PMID 3327803. Retrieved August 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - MARIANNE E. BERNSTEIN (1958). "Studies in The Human Sex Ratio 5. A Genetic Explanation of the Wartime Secondary Sex Ratio" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 10 (1): 68–70. PMC 1931860. PMID 13520702.

- France MESLÉ, Jacques VALLIN, Irina BADURASHVILI (2007). A Sharp Increase in Sex Ratio at Birth in the Caucasus. Why? How? (PDF). Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography. pp. 73–89. ISBN 2-910053-29-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- James WH (1987). "The human sex ratio. Part 1: A review of the literature". Human Biology. 59 (5): 721–752. PMID 3319883. Retrieved August 2011.

- JAN GRAFFELMAN and ROLF F. HOEKSTRA, A Statistical Analysis of the Effect of Warfare on the Human Secondary Sex Ratio, Human Biology, Vol. 72, No. 3 (June 2000), pp. 433-445

- ^ R. Jacobsen, H. Møller and A. Mouritsen, Natural variation in the human sex ratio, Hum. Reprod. (1999) 14 (12), pp 3120-3125

- T Vartiainen, L Kartovaara, and J Tuomisto (1999). "Environmental chemicals and changes in sex ratio: analysis over 250 years in finland". Environmental Health Perspectives. 107 (10): 813–815. doi:10.1289/ehp.99107813. PMC 1566625. PMID 10504147.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Michel Garenne, Southern African Journal of Demography, Vol. 9, No. 1 (June 2004), pp. 91-96

- Michel Garenne, Southern African Journal of Demography, Vol. 9, No. 1 (June 2004), page 95

- Ciocco, A. (1938), Variations in the ratio at birth in USA, Human Biology, 10:36–64

- Jing-Bao Nei (2011), Non-medical sex-selective abortion in China: ethical and public policy issues in the context of 40 million missing females, British Med Bull 98 (1): 7-20

- Jiang B, Li S. Nüxing Queshi yu Shehui Anquan (2009), The Female Deficit and the Security of Society, Beijing: Social Sciences Academic, pp 22-26

- ^ Mazza V, Falcinelli C, Paganelli S; et al. (June 2001). "Sonographic early fetal gender assignment: a longitudinal study in pregnancies after in vitro fertilization". Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 17 (6): 513–6. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0705.2001.00421.x. PMID 11422974.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mevlude Akbulut-Yuksel and Daniel Rosenblum (January 2012), The Indian Ultrasound Paradox, IZA DP No. 6273, Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit, Bonn, Germany

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/4592890.stm

- ^ MacPherson, Yvonne (November 2007). "Images and Icons: Harnessing the Power of Media to Reduce Sex-Selective Abortion in India". Gender and Development. 15 (2): 413–23. doi:10.1080/13552070701630574.

- Age Data C13 Table (India/States/UTs ) Final Population - 2011 Census of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India (2013)

- ^ Age Data - Single Year Age Data - C13 Table (India/States/UTs ) Population Enumeration Data (Final Population) - 2011, Census of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India

- A. Gettis, J. Getis, and J. D. Fellmann (2004). Introduction to Geography, Ninth Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 200. ISBN 0-07-252183-X

- Johansson, Sten; Nygren, Olga (1991). "The missing girls of China: a new demographic account". Population and Development Review. 17 (1): 35–51. doi:10.2307/1972351. JSTOR 1972351.

- Merli, M. Giovanna; Raftery, Adrian E. (2000). "Are births underreported in rural China?". Demography. 37 (1): 109–126. doi:10.2307/2648100. JSTOR 2648100. PMID 10748993.

- Goodkind, Daniel (1999). "Should Prenatal Sex Selection be Restricted?: Ethical Questions and Their Implications for Research and Policy". Population Studies 53 (1): 49–61

- ^ Das Gupta, Monica, "Explaining Asia's Missing Women": A New Look at the Data", 2005 Cite error: The named reference "Gupta_2005" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.01.004, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.01.004instead. - "Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act 1971 - Introduction." Health News RSS. Med India, n.d. Web. 20 Oct. 2013.

- MTP and PCPNDT Initiatives Report Government of India (2011)

- MTP and PCPNDT Initiatives Report Government of India (2011)

- Delhi Laadli scheme 2008 Government of Delhi, India

- http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/jul/13/india-campaign-debate-female-foeticide

- A. Mangai, "Cultural Intervention through Theatre: Case Study of a Play on Female Infanticide/Foeticide," Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 33, No. 44 (Oct. 31 - Nov. 6, 1998), pp. WS70-WS72 http://www.jstor.org/stable/4407327

External links

- UNICEF India

- Female Foeticide in India: A Serious Challenge for the Society

- Documentaries on Female Foeticide

| Social issues in India | |

|---|---|

| Economy | |

| Education | |

| Environment | |

| Family | |

| Children | |

| Women | |

| Caste system | |

| Communalism | |

| Crime | |

| Health | |

| Media | |

| Other issues | |