This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 93.141.151.228 (talk) at 23:41, 15 November 2014 (→Srbe na vrbe). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 23:41, 15 November 2014 by 93.141.151.228 (talk) (→Srbe na vrbe)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

Anti-Serb sentiment is in general a negative sentiment towards the Serbs as a group and historically has been at the basis of persecution of members of the group. The ostensibly synonymous and controversial term Serbophobia has more recently been defined as a historic fear, hatred, and jealousy of Serbs.

The best known historic instance of anti-Serb sentiment was exhibited by the 19th- and 20th-century Croatian Party of Rights, the most extreme elements of which became the Ustaše in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. This fascist organization came to power during World War II and enstated racial laws that specifically targeted Serbs and other minorities, leading to the most severe campaign of World War II persecution of Serbs.

Political scientist David Bruce MacDonald also states that the concept of "Serbophobia" was popularised in the 1980s and 1990s during the re-analysis of Serbian history and became likened to anti-Semitism by Serb nationalists, creating a myth of Serbs as perennial victims which served to justify territorial expansion into neighbouring regions with its ethnic population, which could then be presented as self-defensive and humanitarian.

History

Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary

19th and early 20th century in Croatia

Anti-Serbian sentiment coalesced in Croatia in the 19th century when a part of the Croatian intelligentsia were planning the creation of a Croatian nation-state. Ante Starčević, the leader of the Party of Rights between 1851 and 1896, believed Croats should confront their neighbors, including Serbs. He wrote for example that Serbs were an "unclean race" and with co-founder of the party Eugen Kvaternik denied the existence of Serbs or Slovenes in Croatia, seeing their political consciousness as a threat. During the 1850s Starčević forged a term Slavoserb (Template:Lang-lat) to describe people supposedly ready to serve foreign rulers, initially used to refer to some Serbs and his Croat opponent and later to all Serbs by his followers. The Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878 probably contributed to the development of Starčević's anti-Serb sentiment: He believed that it increased chances for the creation of Greater Croatia. David Bruce MacDonald, however, has explained Starčević's theories could only justify ethnocide but not genocide because Starčević intended to assimilate Serbs as "Orthodox Croats", and not to exterminate them.

Starčević's ideas served as a basis for the destructive politics of his successor Josip Frank who led numerous anti-Serbian incidents. Under Frank's leadership the Party of Rights became obsessively anti-Serb, and such a sentiment was predominant in Croatian political life in the 1880s. British historian C. A. Macartney has stated that because of the "gross intolerance" toward Serbs who lived in Slavonia, the group had to seek protection from Count Károly Khuen-Héderváry, the Ban of Croatia-Slavonia, in 1883. During his reign in 1883-1903, Hungary stimulated division and hatred between Serbs and Croats to conduct its Magyarization policy. Carmichael writes that ethnic division between the Croats and the Serbs at the turn of the 20th century was stoked by nationalist press and was "incubated entirely in the minds of extremists and fanatics, with little evidence that the areas in which Serbs and Croats had lived for many centuries in close proximity, such as the Krajina, were more prone to ethnically inspired violence."

Between the mid-19th and early 20th century there were two factions in the Catholic Church in Croatia: the progressive faction which preferred uniting Croatia with Serbia in a progressive Slavic country, and the conservative faction that was opposed to it. The conservative faction became dominant by the end of the 19th century: The First Croatian Catholic Congress held in Zagreb in 1900 was unreservedly Serbophobic and anti-Orthodox.

The term Serbophobe was used in literary and cultural circles before World War I. Croatian writers Antun Gustav Matoš and Miroslav Krleža have casually described some political and cultural figures as "Serbophobes" (Krleža in the four-volume Talks with Miroslav Krleža, 1985, edited by Enes Čengić; they perceived an anti-Serbian animus in a person's behavior.

Ottoman Macedonia

The Society Against Serbs was a Bulgarian nationalist organization, established in 1897 in Sofia, Principality of Bulgaria. The organization's activists were both "Centralists" and "Vrhovnists" of the Bulgarian revolutionary committees (Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization and Supreme Macedonian Committee), and had up until 1902 murdered at least 43 persons, and wounded 52 persons, who were owners of Serbian schools, teachers, Serbian Orthodox clergy, and other notable Serbs in the Ottoman Empire. Bulgarians also used the term "Serbomans" for Serbs in Macedonia.

World War I

Excerpt from a 1913 Austro-Hungarian order, that banned numerous social-democratic and ethnic Serb cultural societies in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Excerpt from a 1913 Austro-Hungarian order, that banned numerous social-democratic and ethnic Serb cultural societies in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

After the Balkan Wars in 1912—1913 the Austro-Hungarian administration in Bosnia and Herzegovina became Serbophobic. Oskar Potiorek, governor of Bosnia and Herzegovina, closed many Serb societies and significantly contributed to the anti-Serb mood before the outbreak of World War I.

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg in 1914 led to the Anti-Serb pogrom in Sarajevo, where angry Croats and Muslims engaged in violence during the evening of 28 June and much of the day on 29 June. This led to a deep division along ethnic lines unprecedented in the city's history. Ivo Andrić refers to this event as the "Sarajevo frenzy of hate." The crowds directed their anger principally at Serb shops, residences of prominent Serbs, Serbian Orthodox Church, schools, banks, the Serb cultural society Prosvjeta, and the Srpska riječ newspaper offices. Two Serbs were killed that day. That night there were anti-Serb riots in other parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire including Zagreb and Dubrovnik. In the aftermath of the Sarajevo assassination anti-Serb sentiment ran high throughout the Habsburg Empire. Austria-Hungary imprisoned and extradited around 5,500 prominent Serbs, sentenced 460 to death and established predominantly Muslim special militia Schutzkorps which carried on the persecution of Serbs.

The Sarajevo assassination became the casus belli for World War I. Taking advantage of an international wave of revulsion against this act of "Serbian nationalist terrorism," Austria-Hungary gave Serbia an ultimatum which led to World War I. Although Serbs of Austria-Hungary were loyal citizens whose majority participated in its forces during the war, anti-Serb sentiment was systematically inspired while members of the group were persecuted all over the country. Austria-Hungary soon occupied the territory of the Kingdom of Serbia, including Kosovo, boosting already intense anti-Serbian sentiment among Albanians whose volunteer units were established to reduce the number of Serbs on Kosovo. A cultural example of Serbophobia is the jingle "Alle Serben müssen sterben" ("All Serbs Must Die"), which was popular in Vienna in 1914. (It was also known as "Serbien muß sterbien").

Interwar period

Belgrade's centralist policies for the Kingdom of Yugoslavia led to increased anti-Serbian sentiment in Croatia.

World War II

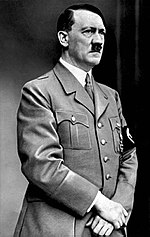

Serbophobia increasingly infiltrated into German Nazi ideology after Adolf Hitler's appointment as chancellor in 1933. The roots of his anti-Serb sentiment can be found in his early life in Vienna, and when he was informed about the Yugoslav coup d'état conducted by a group of pro-Western Serb officers in March 1941, he decided to punish all Serbs as the main enemies of his new Nazi order. The ministry of Joseph Goebbels, with support of the Bulgarian, Italian, and Hungarian press was given the task of stimulating anti-Serb sentiment among Croats, Slovenians and Hungarians. The propaganda of the Axis powers accused the group for persecution of minorities and the establishment of the concentration camps for ethnic Germans in order to justify an attack on Yugoslavia and present Nazi Germany as a force which would save the Yugoslavian people from Serb nationalism. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was invaded again and occupied by Axis powers.

The Axis occupation of Serbia enabled the Ustaše, a Croatian fascist and terrorist organization, to follow their extreme anti-Serbian ideology in the Independent State of Croatia. Their Serbophobia was racist and genocidal. The new Croatian government adopted racial laws, similar to those in Nazi Germany, which aimed at Jews, Roma people and Serbs who were all defined as "aliens outside the national community" and persecuted throughout World War II throughout the Independent State of Croatia (NDH). Between 197,000 and 217,000 Serbs were killed in Croatia by the Ustaše and their Axis allies. Overall, the number of Serbs killed in World War II exceeded 350,000, the majority being massacred by various fascist forces.

Some priests of the Croatian Catholic Church participated in these Ustaša massacres and the mass conversion of Serbs to Catholicism. During the war, about 250,000 people of Orthodox faith that were living within the territory of the NDH were either forced or coerced into converting to Catholicism by the Ustaša authorities. One of the reasons for the close cooperation of the part of Catholic clergy was their anti-Serb position.

After World War II

In the period between World War II and 1948, when Yugoslavia was expelled from Comintern, anti-Montenegrin and anti-Serb sentiment were considered verboten in communist Albania. Nearly four decades later, in the 1986 draft of the Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, concern was expressed that Serbophobia, together with other things, could provoke the restoration of Serbian nationalism with dangerous consequences. The 1987 Yugoslav economy crisis, and different opinions of Serbia and other republics about the best ways to resolve it, exacerbated growing anti-Serbian sentiment among non-Serbs, but also enhanced Serbian support for Serbian nationalism.

Breakup of Yugoslavia

During the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s anti-Serb sentiment flooded Croatia and Kosovo, and because of its independence and association with Serbophobia the Independent State of Croatia would sometimes serve as rallying symbol for people who intended to proclaim aversion toward Serbia. It also of course worked vice versa. And while Serbian nationalism of the time is well-known, anti-Serb sentiment was present among all non-Serb nations of Yugoslavia during its breakup.

In 1997 the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia submitted to the International Court of Justice claims that Bosnia and Herzegovina was responsible for the acts of genocide committed against the Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which had been incited by anti-Serb sentiment and rhetoric communicated through all forms of the media. For example, The Novi Vox, a Muslim youth paper, published a poem titled "Patriotic Song" with the following verses: "Dear mother, I'm going to plant willows; We'll hang Serbs from them; Dear mother, I'm going to sharpen knives; We'll soon fill pits again." The paper Zmaj od Bosne published an article with a sentence saying "Each Muslim must name a Serb and take oath to kill him." The radio station Hajat broadcast "public calls for the execution of Serbs."

Hate speech and derogatory terms

Srbe na vrbe

The slogan Srbe na vrbe!, meaning "Hang Serbs from the willow trees!" (literally, "Serbs on the willows!") originates from a poem of the Slovene politician Marko Natlačen published in 1914, at the beginning of the war of Austria-Hungary against Serbia. It was popularized before World War II by Mile Budak, the chief architect of Ustaše ideology against Serbs, and during World War II there were mass hangings of Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia as part of the Ustaše persecution of the Serbs.

Derogatory terms for Serbs

- Vlachs (Template:Lang-bs,(Template:Lang-hr) - sometimes used in Croatia and Bosnia

- Chetniks (Template:Lang-bs),(Template:Lang-hr)

- Shkije or Shki - an ethnic slur used by some Kosovo Albanians.

Criticism and controversy

The early 20th-century Serbian socialist and newspaper editor Dimitrije Tucović believed that the hatred of Serbia by the Albanian people was caused by Serbian colonialism, which victimised overwhelmingly Albanian Kosovo. Tucović stated that Serbia's attempt to annex Albanian-populated territory in the Balkan wars caused the Albanian people to feel hatred of everything Serbian. He concluded that Serbia wanted access to the sea and the colony, but left without getting to the sea, and by colonising Kosovo created a blood enemy.

The description of Serbophobia has been controversial, as some sources state it runs contrary to the facts. Some controversy with the term purportedly corresponds to its interplay with perceived historical revisionism practiced by the Milosevic government in the 1990s and their apologists afterwards, and the contention that Serbian writers constructed the "myth of Serbophobia," as "an anti-Semitism for Serbs, making them victims throughout history." According to MacDonald, in the 1980s Serbs increasingly began to compare themselves to Jews as fellow victims in world history, which involved tragedising historic events, from the 1389 Battle of Kosovo to the 1974 Yugoslav Constitution, as every aspect of history was seen as yet another example of persecution and victimisation of Serbs at the hands of external negative forces.

Critics associate the use of the term Serbophobia with the politics of Serbian nationalist victimization of the late 1980s and 1990s as described, for example, by former director of the International Crisis Group in the Balkans, Christopher Bennett. According to him, the idea of historic Serb martyrdom grew out of the thinking and writing of Dobrica Ćosić who developed a complex and paradoxical theory of Serb national persecution, which evolved over two decades between the late 1960s and the late 1980s into the Greater Serbian programme. Serbian nationalist politicians have made associations to Serbian "martyrdom" in history (from the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 to the genocide during World War II) to justify Serbian politics of the 1980s and 1990s; these associations being exemplified in Slobodan Milošević's Gazimestan speech at Kosovo Polje in 1989. The reaction to the speech as well as the use of the associated term Serbophobia remains a matter of heated debate. In late 1988, months before the Revolutions of 1989, Milošević accused his critics and political tactics like the Slovenian leader Milan Kučan of "spreading fear of Serbia". The term Serbophobia was often likened to anti-Semitism, and expressed itself as a re-analysis of history where every event that had a negative effect on the Serbs was likened to a "tragedy".

Gallery

-

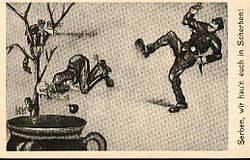

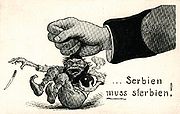

Serbien muss sterbien! ("Serbia must die!"), an Austrian caricature, after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in 1914, depicting Serbia as a little terrorist.

Serbien muss sterbien! ("Serbia must die!"), an Austrian caricature, after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in 1914, depicting Serbia as a little terrorist.

-

Devastated and robbed shops owned by Serbs in Sarajevo during the Anti-Serb pogrom in Sarajevo.

Devastated and robbed shops owned by Serbs in Sarajevo during the Anti-Serb pogrom in Sarajevo.

-

Austro-Hungarian soldiers executing Serb civilians during World War I.

Austro-Hungarian soldiers executing Serb civilians during World War I.

-

The remains of Serbs executed by Bulgarian soldiers in the Surdulica massacre during World War I. An estimated 2,000–3,000 Serbian men were killed in the town during the first months of the Bulgarian occupation of southern Serbia.

The remains of Serbs executed by Bulgarian soldiers in the Surdulica massacre during World War I. An estimated 2,000–3,000 Serbian men were killed in the town during the first months of the Bulgarian occupation of southern Serbia.

-

Order for Serbs and Jews to move out of their home in Zagreb, in the Nazi puppet state during World War II. Also, warning of forcible expulsion for Serbs and Jews who fail to comply.

Order for Serbs and Jews to move out of their home in Zagreb, in the Nazi puppet state during World War II. Also, warning of forcible expulsion for Serbs and Jews who fail to comply.

- Ustaše saw off the head of a Serb, Branko Jungić, in Grabovac, near the town of Bosanska Gradiška. Ustaše saw off the head of a Serb, Branko Jungić, in Grabovac, near the town of Bosanska Gradiška.

-

Ruins of the Church of Holy Salvation, Prizren which was built circa 1330 and destroyed during the 2004 unrest in Kosovo.

Ruins of the Church of Holy Salvation, Prizren which was built circa 1330 and destroyed during the 2004 unrest in Kosovo.

-

14th-century icon from Our Lady of Ljeviš in Prizren, which was damaged in 2004 by rioters.

14th-century icon from Our Lady of Ljeviš in Prizren, which was damaged in 2004 by rioters.

- Adolf Hitler examines the 1930 Gavrilo Princip plaque removed from Sarajevo by German troops and presented to him on his 52nd birthday on April 20, 1941, aboard his special command and control train, Sonderzug Amerika, in Monichkirchen. Adolf Hitler examines the 1930 Gavrilo Princip plaque removed from Sarajevo by German troops and presented to him on his 52nd birthday on April 20, 1941, aboard his special command and control train, Sonderzug Amerika, in Monichkirchen.

See also

- World War II persecution of Serbs

- Jasenovac concentration camp

- 1991 anti-Serb riot in Zadar

- Organ theft in Kosovo

- 2004 unrest in Kosovo

- Panda Bar incident

- Podujevo bus bombing

- Goraždevac murders

Notes

- An essential precondition and follow-up to Serbian machinations in the Krajina and East Slavonia involved proving the existence of a historic nationalist project aimed against the Serbs. The myth of ‘Serbophobia’ (a historic fear, hatred, and jealousy of Serbs that Serb nationalists have likened to anti-Semitism) allowed nationalists to trace a continuous legacy of hatred and violence against the Serbs among the Croats. The actions of the JNA and Serbian irregular militias in Croatia could therefore be presented, both at home and to the outside world, as self-defensive and humanitarian – saving the Krajina Serbs from annihilation. Balkan Holocausts?: Serbian and Croatian Victim-centred Propaganda and the War in Yugoslavia, By David Bruce MacDonald, Manchester University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-7190-6467-8, p. 82-83 (Google Books)

- Kurt Jonassohn; Karin Solveig Björnson (January 1998). Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations: In Comparative Perspective. Transaction Publishers. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-4128-2445-3. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

Anti-Serbian sentiment had already been expressed throughout the nineteenth century when Croatian intellectuals began to make plans for their own national state. They viewed the presence of more than one million Serbs in Krajina and Slavonia as intolerable.

- ^ Viktor Meier (15 April 2013). Yugoslavia: A History of Its Demise. Routledge. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-134-66511-2. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

His ideas...brought Croats to a course confrontation to their neighbors

Cite error: The named reference "Meier2013" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - Carmichael 2012, p. 97

For Starčević... Serbs were 'unclean race' ... Along with ... Eugen Kvaternik he believed that 'there could be no Slovene or Serb people in Croatia because their existence could only be expressed in the right to a separate political territory.

- John B. Allcock; Marko Milivojević; John Joseph Horton (1998). Conflict in the former Yugoslavia: an encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-87436-935-9. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

Starcevic was extremely anti-Serb, seeing Serb political consciousness as a threat to Croats.

- Tomasevich (2001), p. 3

In polemics of the 1850's, Starčević also coined a misleading term - "Slavoserb", derived from the Latin word "sclavus" and "servus" to denote persons ready to serve foreign rulers against their own people.

- Carmichael 2012, p. 97

- MacDonald (2002), p. 87

- Robert A. Kann (1980). A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526-1918. University of California Press. p. 447. ISBN 978-0-520-04206-3. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

... in the case of Frank's followers... strongly anti-Serb

- Stephen Richards Graubard (1999). A New Europe for the Old?. Transaction Publishers. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4128-1617-5. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

Under Josip Frank, who carried the rightists into a new era, the party became obsessively anti- Serbian.

- Charles Jelavich (1986). The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804-1920. University of Washington Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-295-80360-9. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

In the 1880s this group, with its strident Croatian nationalism and its anti-Serbian tone, clearly dominated the Croatian political scene.

- MacDonald (2002), p. 88

- MacDonald (2002), p. 88

- Carmichael 2012, p. 97

- ^ Sabrina P. Ramet (1998). Nihil Obstat: Religion, Politics, and Social Change in East-Central Europe and Russia. Duke University Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-8223-2070-8. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

Thus, from the mid-nineteenth century until the 1920s, the church in Croatia was riven into two factions: the progressives, who favored the incorporation of Croatia into a liberal Slavic state ... and the conservatives,... who were loath to bind Catholic Croatia to Orthodox Serbia.

Cite error: The named reference "Ramet1998" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - Hadži Vasiljević, Jovan (1928). Četnička akcija u Staroj Srbiji i Maćedoniji. p. 14.

- ^ Richard C. Frucht (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 644. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

The Balkan Wars left Serbia as the region's strongest power. Serbia's relationship with Austria-Hungary remained an- tagonistic, and the Habsburg administration in Bosnia- Hercegovina became anti-Serb....

Cite error: The named reference "Frucht2005" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - Mitja Velikonja (5 February 2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

The anti-Serb policy and mood that emerged in the months leading up to the First World War were the result of the machinations of Gen. Oskar von Potiorek (1853-1933), Bosnia- Herzegovina's heavy-handed military governor.

- Daniela Gioseffi (1993). On Prejudice: A Global Perspective. Anchor Books. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-385-46938-8. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

...Andric describes the "Sarajevo frenzy of hate" that erupted among Muslims, Roman Catholics, and Orthodox believers following the assassination on June 28, 1914, of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo...

- Sarajevo: a biography, by Robert J. Donia. Google Books. 29 June 1914. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- Beginning the twentieth century: a history of the generation that made the war, by Joseph Ward Swain. Google Books. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- John Richard Schindler (1995). A hopeless struggle: the Austro-Hungarian army and total war, 1914-1918. McMaster University. p. 50. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

...anti-Serbian demonstrations in Sarajevo, Zagreb and Ragusa.

- Yugoslavia's bloody collapse: causes, course and consequences, by Christopher Bennett. Google Books. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- Tomasevich (2001), p. 485

The Bosnian wartime militia (Schutzkorps), which became known for its persecution of Serbs, was overwhelmingly Muslim.

- Herbert Kröll (28 February 2008). Austrian-Greek encounters over the centuries: history, diplomacy, politics, arts, economics. Studienverlag. p. 55. ISBN 978-3-7065-4526-6. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

...arrested and interned some 5.500 prominent Serbs and sentenced to death some 460 persons, a new Schutzkorps, an auxiliary militia, widened the anti-Serb repression.

- ^ Lajčo Klajn (1 January 2007). The Past in Present Times: The Yugoslav Saga. University Press of America. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7618-3647-6. Retrieved 1 September 2013. Cite error: The named reference "Klajn2007" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Stevan K. Pavlowitch (January 2002). Serbia: The History Behind the Name. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-85065-477-3. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- Banac 1988, p. 297

... Vienna had its reasons for encouraging the already strong anti-Serbian sentiment among the Albanians...

- Gustav Regler; Gerhard Schmidt-Henkel; Ralph Schock (2007). Werke. Stroemfeld/Roter Stern. p. 46. ISBN 978-3-87877-442-6. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

Mit Kreide war an die Waggons geschrieben: »Jeder Schuß ein Russ', jeder Stoß ein Franzos', jeder Tritt ein Brit', alle Serben müssen sterben.« Die Soldaten lachten, als ich die Inschrift laut las. Es war eine Aufforderung, mitzulachen.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - United States. Congress. Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (1993). Human rights and democratization in Croatia. The Commission. p. 3. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

Increasing centralization by Belgrade, however, encouraged anti-Serbian sentiment in Croatia,

- Stephen E. Hanson; Willfried Spohn (1 January 1995). Can Europe Work?: Germany and the Reconstruction of Postcommunist Societies. University of Washington Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-295-80188-9. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

German anti-Serbian sentiment increased after Hitler's ascent to power in 1933. His Serbo- phobia, rooted in the years of his youth spent in Vienna, was virulent. As a result, Nazi ideology became permeated with anti-Serbian sentiment.

- Stevan K. Pavlowitch (2008). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. Columbia University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-231-70050-4. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

He wanted to punish the Serbs, the main disturbers of the European order. In him the anti-Serbian Austrian streak erupted that went back to before the First World War.

- "Ustasa (Croatian political movement) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- Tomasevich (2001), p. 391

...Serbia proper was under strict German occupation, allowed Ustashas to pursue their radical anti-Serbian policy

- Aleksa Djilas (1991). The Contested Country: Yugoslav Unity and Communist Revolution, 1919-1953. Harvard University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-674-16698-1. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

It was racist and genocidal hatred of people who merely had different national consciousness

- Rory Yeomans; Anton Weiss-Wendt (1 July 2013). Racial Science in Hitler's New Europe, 1938-1945. U of Nebraska Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-8032-4605-8. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

The Ustasha regime ... inaugurated the most brutal campaign of mass murder against civilian population that Southern Europe has ever witnessed... The campaign of mass murder and deportation against the Serb population was initially justified on racial scientific principles. ...

- Frederick C. DeCoste; Bernard Schwartz (2000). The Holocaust's Ghost: Writings on Art, Politics, Law and Education ; [includes Papers from the Conference, Held at the University of Alberta, Oct. 1997]. University of Alberta. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-88864-337-7. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

The new Croatian government quickly adopted Nazi-type racial laws and genocidal tactics to deal with Roma, Serbs and Jews, whom these laws termed "aliens outside the national community".

- "Resistance to the Persecution of Ethnic Minorities in Croatia and Bosnia During World War II (9780773447455): Lisa M. Adeli: Books". Amazon.com. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- Žerjavić, Vladimir (1993). Yugoslavia - Manipulations with the number of Second World War victims. Croatian Information Centre. ISBN 0-919817-32-7.

- Bideleux, Robert (2007). The Balkans: a post-communist history. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-22962-6.

- "The Serbs and Croats: So Much in Common, Including Hate, May 16, 1991". The New York Times. 16 May 1991. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ Sabrina P. Ramet (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918-2005. Indiana University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

... some priests were taking part in Ustasa atrocities against Serbs ...

Cite error: The named reference "Ramet2006" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - Tomasevich (2001), p. 542

- Tomasevich (2001), p. 391

Close collaboration between Ustaša and part of catholic clergy followed... above all anti-Serbian...

- Robert Elsie (2005). Albanian Literature: A Short History. I.B.Tauris. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-84511-031-4. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

After relations with Yugoslavia were broken off in 1948, it is quite likely that expressions of anti-Montenegrin or anti-Serb sentiment would no longer have been considered a major sin in Party thinking.

- "SANU". Web.archive.org. 16 June 2008. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

The present depressing condition of the Serbian nation, with chauvinism and Serbophobia being ever more violently expressed in certain circles, favor of a revival of Serbian nationalism, an increasingly drastic expression of Serbian national sensitivity, and reactions that can be volatile and even dangerous.

- Robert Bideleux; Professor Richard Taylor (15 April 2013). European Integration and Disintegration: East and West. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-134-77522-4. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

By 1987 accelerating inflation and rapid depreciation of the dinar were strengthening Slovene and Croatian demands for sweping economic liberalization, but these were blocked by Serbia. This exacerbated the growing anti-Serbian sentiments among non-Serbs, but also enhanced Serbian support for Milošević's nationalism and his manipulation of the Kosovo issue, culminating in the abolition of the autonomy of that region.

- Sabrina P. Ramet (2007). The Independent State of Croatia 1941-45. Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-415-44055-4. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

Because of its independence from Belgrade (though not from Berlin) and because of its association with anti-Serb and anti-Allied politics, the NDH would later serve as rallying symbol for those who wanting to declare their antipathy toward Serbia (during the War of Yugoslav secession)...

- ^ INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE 17 December 1997 Case Concerning Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishmnent of the Crime of Genocide. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- Dr. Božo Repe (2005). "Slovene History – 20th century, selected articles" (PDF). Department of History of the University of Ljubljana. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- Petition of 120 Croatian intellectuals. "O Mili Budaku, opet: Deset činjenica i deset pitanja – s jednim apelom u zaključku" (in Croatian). Index.hr. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Vinko Nikolić (1990). Mile Budak, pjesnik i mučenik Hrvatske: spomen-zbornik o stotoj godišnjici rođenja 1899-1989. Hrvatska revija. p. 55. ISBN 978-84-599-4619-3. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

...gdje je Budak, izgleda po prvi puta, upotrijebio krilaticu «Srbe na vrbe»

- Banac 1988, p. 257

"Despite the apparent hostility toward the royal house, overt anti-Serb sentiment was rarely displayed and then mainly in Hrvatsko Zagorje where slogans against the "Vlachs" (derogatory term for Serbs) were raised."

- Pål Kolstø (2009). Media Discourse and the Yugoslav Conflicts: Representations of Self and Other. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-4094-9164-4. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

The hostile 'them' were labelled either as the abstract but omnipresent 'aggressor' or as the stereotypical 'Chetniks' and 'Serbo-communists'. Other derogatory references in Večernji list,...

- "Civil Rights Defense Minority Communities, March 2006" (PDF). Web.archive.org. 28 September 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- NIN. nedeljne informativne novine. Politika. 2005. p. 6.

Албанци Србе зову Шкије, и то им је сасвим у реду, иако је то исто увредљиво као српски погрдни назив за Албанце

- Dimitrije Tucović, Serbia and Albania: A Contribution to the Critique of the Conqueror Policy of the Serbian Bourgeoisie

- Dimitrije Tucović, Srbija i Arbanija (u Izabrani spisi, knjiga II, str. 131) Prosveta, Beograd, 1950.

- Dimitrije Tucović, Srbija i Arbanija (u Izabrani spisi, knjiga II, str. 117) Prosveta, Beograd, 1950.

- MacDonald (2002), pp. 82-88

- MacDonald (2002), p. 83

- MacDonald (2002), p. 7

- Comment: Serbia's War With History by C. Bennett, Institute for War & Peace Reporting, 19 April 1999

- Comment: Serbia's War With History by C. Bennett, Institute for War & Peace Reporting, 19 April 1999

- Comment: Serbia's War With History by C. Bennett, Institute for War & Peace Reporting, 19 April 1999

- Communism O Nationalism!, Time Magazine, 24 October 1988

- MacDonald, D. B. (2003), pp. 82-88

- Mitrović 2007, p. 223.

References

- Banac, Ivo (1988), The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics, Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8014-9493-2, retrieved 1 September 2013

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Vol. 2. San Francisco: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3615-4.

- MacDonald, David Bruce (2002). Balkan Holocausts?: Serbian and Croatian Victim Centred Propaganda and the War in Yugoslavia. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-6466-X.

- Mitrović, Andrej (2007). Serbia's Great War, 1914-1918. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-476-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carmichael, Cathie (2012), Ethnic Cleansing in the Balkans: Nationalism and the Destruction of Tradition, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-47953-5, retrieved 31 August 2013

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Ovey, Michael. "Victim Chic? The Rhetoric of victimhood". Cambridge Papers.

- Globalizing the Holocaust: A Jewish "useable" past in Serbian nationalism, by David McDonald, University of Otago, New Zealand

Use in various languages

- Neue Serbophilie und alte Serbophobie, "New Serbophilia and Old Serbophobia", a 2000 Junge Welt article by Werner Pirker, in German

- Archived (Date missing) at lire.fr (Error: unknown archive URL), a 1999 article by Catherine Argand from Lire, a French literary magazine, in French

- Europa e nuovi nazionalismi, a 2001 article by Luca Rastello, in Italian

- Archived (Date missing) at 7days.ru (Error: unknown archive URL), a 2000 Sevodnya article by Alexei Makarkin, in Russian

- Ku është antimillosheviqi?, a 2000 AIM article by Igor Mekina, in Albanian

Template:Anti-cultural sentiment

| Anti-Slavic sentiment | |

|---|---|