This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Jaguar (talk | contribs) at 22:08, 16 February 2015 (GA). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:08, 16 February 2015 by Jaguar (talk | contribs) (GA)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

The Rose-Baley Party was the first European American emigrant wagon train to traverse the 35th parallel route known as Beale's Wagon Road, established by Edward Fitzgerald Beale, from Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico to the Colorado River near present-day Needles, California.

In 1858, a wealthy businessman from Keosauqua, Iowa, Leonard John Rose, formed the party after having been inspired by stories from gold miners returning from California. He subsequently financed one of the best-equipped wagon trains of the era, purchasing an animal stock that included twenty of Iowa and Missouri's finest trotting horses and two hundred head of thoroughbred red Durham cattle. He also acquired four large prairie schooner covered wagons and three yoke of oxen to pull the massive vehicles. The Rose company left Iowa in early April, and in mid-May they were joined by the Baley company, led by a forty-four-year-old veteran of the Black Hawk War, Gillum Baley. Their combined outfits numbered twenty wagons, forty men, fifty to sixty women and children, and nearly five hundred head of cattle.

On August 30, 1858, after having traveled more than 1,200 miles (1,900 km) in four months, the Rose-Baley Party were attacked by three hundred Mohave warriors as they prepared to cross the Colorado River. Eight members of the party were killed, including five children, and twelve wounded. The emigrants held off their attackers, killing seventeen Mohave, but decided to backtrack more than 500 miles (800 km) to Albuquerque, New Mexico, instead of continuing on to their intended destination in Southern California.

E.F. Beale expedition

In October 1857, an expedition led by Edward Fitzgerald Beale, known as E.F. Beale, was tasked with establishing a trade route along the 35th parallel from Fort Smith, Arkansas to Los Angeles, California. The wagon trail began at Fort Smith and continued through Fort Defiance, Arizona before crossing the Colorado River near present-day Needles, California. The Mohave chief, Irataba, helped the expedition, and Beale named the location where they crossed the river, en route to California, Beale's Crossing. Beale described the route, "It is the shortest from our western frontier by 300 miles (480 km), being nearly directly west. It is the most level: our wagons only double-teaming once in the entire distance, and that at a short hill, and over a surface heretofore unbroken by wheels or trail on any kind. It is well-watered: our greatest distance without water at any time being 20 miles (32 km). It is well-timbered, and in many places the growth is far beyond that of any part of the world I have ever seen. It is temperate in climate, passing for the most part over an elevated region. It is salubrious: not one of our party requiring the slightest medical attendance from the time of our leaving to our arrival ... It crosses the great desert (which must be crossed by any road to California) at its narrowest point."

Formation

During the spring and summer of 1858, a large emigrant wagon train became the first to traverse Beale's 35th parallel route to Mohave country. A wealthy businessman from Keosauqua, Iowa, Leonard John Rose, known as L.J. Rose, formed the party with his family of seven, his foreman, Alpha Brown, and his family, and seventeen grubstakers, workers who were not paid a salary, but given food and board in exchange for their services. Rose was born in Rottenburg, Germany in 1827; he immigrated to the United States when he was eight years old. He identified what motivated him to form the wagon train and leave Iowa, where he had built several successful businesses:

In 1858 some miners who had just returned from California so fired my imagination with descriptions of its glorious climate, wealth of flowers, and luscious fruits, that I was inspired with an irresistible desire to experience in person the delights to be found in the land of plenty.

In preparation for the venture, Rose sold most of his property and settled his debts, amassing what was then a small fortune of $30,000. This enabled him to finance one of the best equipped wagon trains of the era, including an animal stock that featured two Morgan fillies, valued at $350 each, and a Morgan stallion named Black Morrill, valued at $2,500. He also purchased twenty of Iowa and Missouri's finest trotting horses and two hundred head of thoroughbred red Durham cattle, which he planned to resell in California for profit. To complete the train, Rose acquired four large prairie schooner covered wagons and three yoke of oxen to pull the massive vehicles. Three of the schooners carried equipment and supplies, and the fourth was used by Alpha Brown and his family. Rose's family traveled in a small wagon known as an ambulance, which was pulled by two mules.

In April 1858, four families from northwestern Missouri – two Baleys and two Hedgpeths – left for California. Several factors influenced their decision to leave the Midwest, including the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which granted Nebraska admittance into the Union as a free territory and Kansas the right to determine whether they would be free or slave-holding. The resulting tensions between pro-slavery and anti-slavery groups drove conflict near the Missouri border, with Kansas earning the unofficial nickname, "Bleeding Kansas". The ensuing violence spilled over into Missouri's western counties, including Nodaway, where the Baleys and Hedgpeths lived. The financial Panic of 1857 further exacerbated the atmosphere of uncertainty, driving many Midwesterners to seek a better life in California. The combined Baley-Hedgpeth outfits were led by a forty-four-year-old veteran of the Black Hawk War, Gillum Baley, and comprised eight Murphy wagons, sixty-two oxen, seventy-five head of cattle, and several riding horses. They employed half-a-dozen grubstakers to tend their stock.

Journey

The Rose company left Iowa in early April; their first significant destination was Kansas City, Missouri, then named Westport, where they crossed the Missouri River on a steamboat. In mid-May, they were joined by the Baley company while resting at Cottonwood Creek, near present-day Durham, Kansas. In the interests of safety, the groups agreed to travel together; their combined companies, though never formally merged, numbered twenty wagons, forty men, fifty to sixty women and children, and nearly five hundred unbranded head of cattle.

Whereas most emigrants who traveled from the Midwestern United States to the West Coast took the Oregon Trail, in 1858 concerns about the Mormon War led many, including the Rose-Baley Party, to avoid Utah by taking the Santa Fe Trail to New Mexico, where a viable southern route could then be taken to California. The Santa Fe Trail followed the Arkansas River to a spot near Cimarron, Kansas, where it split into two paths: the Mountain Branch that continued into the mountains of southern Colorado, and the Cimarron Cutoff that avoided mountains, but traversed the fifty-mile-wide Cimarron Desert before the paths met near Las Vegas, New Mexico. The Cimarron Cutoff was 100 miles (160 km) shorter and much easier to navigate with large wagons, but it also led its travelers through the territory of the feared Comanche and Kiowa people. Nonetheless, the Rose-Baley Party chose this path.

They reached Albuquerque, New Mexico on June 23, where several families, including the Udell's, the Dalys, the Hollands, and their livestock joined the Rose-Baley Party before making the journey to the Colorado River by way of Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico, where, despite objections from the lone dissenter, John Udell, they would become the first emigrant train to venture onto Beale's Wagon Road. Udell later explained his concern, "I thought it was preposterous to start on so long a journey with so many woman and helpless children, and so many dangers attending the attempt." While visiting Albuquerque, the emigrants first learned of the recently surveyed road. Townspeople and army officers, including Benjamin Bonneville, encouraged them to take the new route, which was shorter than the established southern trails by 200 miles (320 km), or approximately thirty days travel. They were also told that there was a reliable supply of food and water along the way, and the area was free of hostile Native Americans. E.F. Beale, who was in Washington, D.C. making recommendations to members of Congress and the War Department at the time, was less enthusiastic:

I regard the establishment of a military post on the Colorado River as an indispensable necessity for the emigrant over this road; for although the Indians living in the rich meadow lands are agricultural, and consequently peaceable, they are very numerous, so much so that we counted 800 men around our camp on the second day after our arrival on the banks of the river. The temptation of scattered emigrant parties with their families, and the confusion of inexperienced teamsters, rafting so wide and rapid a river with their wagons and families, would offer too strong a temptation for the Indians to withstand.

Beale suggested that, in addition to a military fort, the route was also in need of bridges and dams to ensure safe travel and provide a reliable water supply. His report explicitly advised that no emigrants should attempt the passage until all of those things had been accomplished. Further complicating the journey, the only pockets of civilization between Albuquerque and San Bernardino, California, a distance of 600 miles (970 km), were the Zuni and Laguna pueblos. At the insistence of US Army officers stationed in Albuquerque, the party was accompanied by Jose Manuel Savedra, a Mexican guide who had traveled with Beale during his initial survey of the route, and his interpreter, Petro. Udell, a 62-year-old Baptist minister who had left his home in Missouri with his wife, Emily, kept a daily journal of the party's travels, recording the locations of their campsites and their estimated distance from Missouri, the weather and road conditions, and the availability of grass, water, and wood.

The Rose-Baley Party left Albuquerque on June 26 and began crossing the Rio Grande on a ferry. Three days later, as the last of their outfit crossed, they suffered their first casualty when one of Rose's men, Frank Emerdick, drowned in the river. Despite a somber mood, they traveled for the next five days and did not stop and celebrate on Independence Day, as would most westbound emigrants. On July 5, they reached the Zuni Mountains, a branch of the Rocky Mountains; two days later they traversed the Continental Divide of the Americas, which, although 8,000 feet (2,400 m) to 9,000 feet (2,700 m) feet in elevation, was a relatively easy passage thanks to Beale's road building effort. On July 7, they camped near El Morro National Monument, then called Inscription Rock, and several members of the group, including Rose and Udell, carved their names into stone – a tradition dating back to 1605. Udell's inscription indicated that they were aware of being the first emigrants in the region.

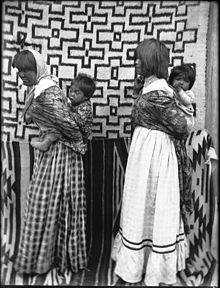

On July 10, the Rose-Baley Party reached Zuni Pueblo, then home to as many as two thousand agricultural Native Americans. They spent several hours visiting and sightseeing, and the friendly Zuni were happy to sell them cornmeal and vegetables, as this was the last such opportunity to purchase supplies until San Bernardino, some 500 miles (800 km) away. This is most likely the first time the Zuni had encountered European women and children, and the first time the emigrants had ever seen people with albinism, which, though exceedingly rare, was present in the Zuni population in significant numbers. They left Zuni Pueblo late that afternoon and began to embark across unfamiliar territory that, until now, had only been traversed by mountain men, explorers, Spanish missionaries, and Native Americans. The Rose-Baley Party had previously enjoyed the benefits of a primitive but well-established trail; however, at this point they became the first emigrant wagon train to venture onto the untested Beale's Wagon Road.

Beale's Wagon Road

Although Beale had hauled several wagons over the route, in 1858 it was a primitive survey trail marked by a few stone cairns and some scattered wagon tracks. Much of the road followed existing human and animal trails, and – although potable water was sporadically available – there were also long stretches called jornadas, where it was scarce. In the area between the San Francisco Peaks and the Colorado River, wood, water, and grass were in short supply.

Because Beale's Wagon Road crossed territory that consisted mainly of the Colorado Plateau's rocky high desert, the next water available to the Rose-Baley Party was at a spot named Jacob's Well, located 36 miles (58 km) west of Zuni Pueblo and 32 miles (51 km) west of their July 10 campsite. Accordingly, the emigrants were careful to not get lost between watering holes. After traveling for more than half a day, they rested and watered their stock at the well, which produced brackish but acceptable water. Later that evening, they trekked another 8 miles (13 km) to Navajo Springs, where they camped for the night and rested the next day, having covered more than 40 miles (64 km) during the last forty-eight hours over a nearly trackless desert that left them dehydrated and exhausted.

After Navajo Springs, the next available water was 40 miles (64 km) distant, at the Little Colorado River. In between was an area that is now home to Petrified Forest National Park, and several members of the party gathered souvenirs of petrified wood there. They reached the Little Colorado at a spot near present-day Holbrook, Arizona, on July 16, and although the river was brackish and underscored with quicksand, the emigrants were able to secure drinkable water by digging holes in the riverbank that allowed sediment to settle until the water was clear enough for consumption. Next, they followed the river 85 miles (137 km) to Canyon Diablo.

On July 18, Udell recorded that spirits were high amongst the Rose-Baley Party: "Our large company continue to be harmonious, friendly, and kind to each other ... General good health prevails ... Travel today, 10 miles (16 km), and 1,112 from the Missouri River." The Rose-Baley Party diverged from the Little Colorado River where it meets Canyon Diablo, near present-day Winslow, Arizona. Uncertain where the next source of clean water was, they decided to camp near the canyon, where they successfully hunted for game while searching for a fresh spring. By the late afternoon of July 24, Savedra returned to camp and reported that they had found water 17 miles (27 km) away at Walnut Creek, now part of Walnut Canyon National Monument. They immediately packed up their camp and left, as they were becoming accustomed to evening and night travel, which allowed them to refrain from exertion during the peak heat of the day. They covered 20 miles (32 km) on July 25 before stopping near a spring in the pine-covered foothills of Arizona's tallest mountains, the San Francisco Peaks, which can be seen for 100 miles (160 km) in most directions. The range's cool forests gave them a much-needed respite from the intense heat and aridity of the high plains desert.

The Rose-Baley Party so enjoyed their camp, near present-day Flagstaff, Arizona, they decided devote a few extra days to recuperation and sightseeing, and several members of the wagon train climbed Humphreys Peak, which at 12,633 feet is the highest point in Arizona. While climbing the mountain, they came across a large snowfield and were amazed to see snow and ice in late July. Before their decent, they entertained themselves by pushing a massive boulder down the mountainside. Up to this point, the emigrants had enjoyed a primitive but decent road, good small game hunting, and a consistent supply of water, grass, and wood. They had experienced "beautiful and interesting" scenery and encountered only friendly Native Americans; however, a drastic change in these conditions was imminent.

On July 29, Savedra informed the Rose-Baley Party, now camped near Leroux Springs, that the next reliable drinking water was seventy or 80 miles (130 km)away, and there would not be a closer source until the rainy season in October and November. This distance far exceeded what most animals could travel without water, and several members of the party were opposed to proceeding any further west until another source had been found. Udell disagreed, "I contended that we had better travel on, for, with careful and proper treatment, we could get the stock through to water, and if we remain here until the rainy season, in all human probability our provisions would be exhausted, and we should parish with starvation." Despite his pleas, nobody wanted to go on until they had located potable water, so six men agreed to undertake a search in hopes that Savedra had overlooked a closer source. Two days later, a man returned to camp and reported that a spring had been found 15 miles (24 km) west, but its supply was so sparse that it could not meet the needs of the entire wagon train at once. After a thorough debate it was decided that, despite stern warnings from Army officers in Albuquerque against splitting into smaller groups, the best course of action was to divide the train in two and water their stock separately.

On August 1, the Rose company ventured west without the Baley company, who waited one full day before starting out from Leroux Springs. In the meantime, the search party had located enough springs to sustain them for the next 50 miles (80 km). Several days later, the party reached their last known source of water, and Savedra informed them that there was not another for 60 miles (97 km), or three days travel. Because that was too long for their animals to travel without water, the party decided to backtrack approximately 26 miles (42 km) to the location of the last reliable supply at Cataract Canyon, in present-day Canyonlands National Park. Udell again protested to no avail, recording in his journal that night: "Had there been a road that I could have traveled without a guide, I should have gone on and risked the consequences." Having trekked 52 miles (84 km)without clean water, the party's stock had grown extremely thirsty. The supply at Cataract Canyon was limited, and it contained what the emigrants called "wigglers"; however, they had no choice but to drink from, and allow their animals to drink from, the less than ideal source. By August 9, the Rose-Baley Party had begun to lose confidence in Savedra's ability to find water, and like Beale before them had been forced to do their own scouting for the precious resource. They had taken to building casks out of pine in hopes that they could gather enough in containers to last them until the next acceptable supply. Udell wrote, "Our water still holds out ... like the widow's cruse of oil, and tastes more pleasant, having been stirred up so often for us."

On August 13, the area received a substantial rainfall that marginally eased the Rose-Baley Party's concerns regarding the scarcity of water in the region. Later that evening, the men who had been searching for it during the last five days returned to camp and reported that they had found an acceptable source 40 miles (64 km) distant and another 80 miles (130 km) away. The emigrants spent the next morning filling casks and preparing for travel; they left late that afternoon, and after having trekked continuously for nearly twenty-four hours arrived at Partridge Creek the next day. That night a thunderstorm filled the creek with rainwater, further easing their concerns; however, after traveling 20 miles (32 km) the following day to a canyon near Mount Floyd, they realized that the recent rainfalls has not reached that far, forcing them to make yet another dry camp on August 17.

On August 18, after having traveled the last 85 miles (137 km) without reliable grass or water, the Rose-Baley Party located a field and a spring that were sufficient to satisfy their stock. That night, despite posting round-the-clock guards, a mare and a mule went missing, and three searchers were sent to find them. They tracked the animals to a deep canyon, where Native Americans hiding in the rocks shot arrows at the emigrants. Savedra noticed them watching the party from the nearby foothills the following day, and was able to draw them into camp using sign language. The Natives, who were most likely Hualapai, could speak a few words of Spanish and English, and Savedra was able to communicate with them using their dialect and sign language. They admitted to having the group's missing animals, but insisted that the Mohave had stolen them. They repeatedly thumped their chest while uttering, "Hanna, Hanna", meaning "good" Native, insisting that the Mohave were "bad" Natives.

Savedra knew that, because the Mohave rarely ventured this far from their homelands, the Hualapai had most likely taken the animals, which were returned the following morning as the party camped at Peach Springs. The animals were led back by twenty-five Natives hoping for compensation in return, as Udell explained: "It was soon evident that they expected very extravagant rewards, all expecting shoes, clothing, and trinkets, besides some cattle ... many remained in camp with us that night, doubtless for the purpose of stealing, but the guard kept so sharp a lookout that they found no opportunity." On August 20, the party awoke to another fifty Hualapai anticipating gifts in exchange for the return of the stolen animals. The Natives left around noon, after receiving tobacco, trinkets, and food, but the emigrants noticed that six oxen were missing. A search team quickly located four carcasses that had been stripped of their flesh; the other two animals were found nearby, having been recently killed, but not yet butchered. That night, the Rose-Baley Party decided to once again split their wagon train in response to the scarcity of water. As they journeyed from their campsite at Peach Springs to the Colorado River more than 100 miles (160 km) away, they were almost continuously harassed by Natives, who sent arrows flying into their wagon train during the day and snuck into their camp at night, attempting to steal anything they could.

Colorado River

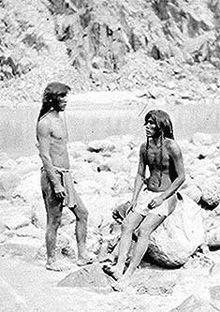

In the late afternoon of August 27, 1858, the Rose-Baley Party reached the Black Mountains. They made their crossing at Sitgreaves Pass, elevation 3,652 feet and named after Lieutenant Lorenzo Sitgreaves, who led an expedition party to the region in 1851. From the crest they could see the Colorado River in the distance. Having traveled all night and worked continuously during the morning and afternoon, the Rose-Baley Party stopped to prepare their first meal of the day. While they were cooking, a small group of Mohave warriors approached and asked, in a combination of broken English and Spanish, how many people their wagon train included and whether they intended to permanently settle near the Colorado River. The Mohave, who appeared friendly and had brought with them corn and melons, which they sold to the emigrants, were promised that the wagon train planned to travel through the region en route to their intended destination in Southern California. This seemed to appease the Natives, many of whom helped the party during their rigorous decent down the western slope of the Black Mountains to the Colorado River below. The emigrants were now entering the domain of the Mohave, near present-day Needles, California.

By midnight, the Baley company had fallen behind the Rose company and decided to stop and make a mountain camp while Rose and others continued to the Colorado River, where they planned to water their combined stock and build a raft in preparation for the impending river crossing. By noon on August 28, Rose had reached a patch of Cottonwood trees about one mile from the river, where their oxen were unhitched and allowed to join the loose stock now excitedly racing towards the water. There the emigrants encountered more Mohave, but unlike the friendly ones that greeted them at Sitgreaves Pass, these were decidedly rude and hostile. After a thorough watering, the work oxen were returned to the wagons. Rose and his wife, Amanda, decided to scout the river bank for a suitable campsite, exiting their wagon to make the journey by foot. Soon afterward, an aggressive Mohave placed his hand on her shoulder and bosom, and she ran back, terrified, to the relative safety of their wagon. Rose, not wanting to incite the Mohave, ignored the incident and continued to the river. Other Mohave harassed Alpha Brown's family, briefly threatening to take his wife's dress and abduct their son. That danger was averted, but many Mohave set about driving off and slaughtering, in plain sight, several of the party's cattle before leaving the emigrants alone at their encampment, some two hundred yards from the river and 10 miles (16 km) away from the Baley company's mountain camp.

The following morning, the emigrants moved their camp to the river bank to facilitate easier watering of their stock. They were visited around noon by twenty-five warriors and a Mohave sub-chief, who heard their complaints about the killing of their livestock and assured them that no further depravations would occur, and that they could cross the Colorado as they pleased. About one hour later, another chief and several warriors approached the camp; after receiving gifts, they left without incident. The emigrants sensed that the chief who granted them passage was hiding something, but they continued to labor nonetheless. By noon, the party had moved their camp closer to where they planned to cross, about a mile downriver near a patch of cottonwood trees that were suitable for building rafts.

Massacre

At approximately 2 p.m. on August 30, 1858, the emigrants camped near the river were aroused by the screams of Alpha Brown's step-daughter, Sallie Fox, who had been playing in a wagon when she noticed several Mohave creeping in the tall grass nearby. Three hundred warriors then let out terrifying "war whoops" as they sent arrows flying into the camp, mortally wounding Rose's foreman, Alpha Brown.

Several white men were felled by arrows and clubs as the women frantically fled with their children to the protection offered by their covered wagons. The Mohave warriors then turned their attention to the animals drinking at the river, killing Black Morrill as the stallion lurched at them. After several hours of fighting, an especially tall Mohave chief, who appeared to be leading the attack, stepped out in front of his warriors and taunted the emigrants, as if to dare them to try to kill him. Gillum Baley, a veteran of the Black Hawk War and a noted marksmen, accepted the challenge and was able to take the chief down with a single rifle shot from a distance. Demoralized, the Mohave warriors retrieved the chief's body and retreated from the battle. Rose and what remained of the attacked group then sneaked back to the mountain camp and joined the others. In all, eight members of the Rose-Baley party were killed, including five children, and twelve wounded; of the train's livestock, only ten mules and horses and seventeen cattle remained. The emigrants killed approximately seventeen Mohave warriors.

With the wounded in one wagon, the children in another, and the healthy adults on foot, the Rose-Baley Party began their "torturous" five hundred-mile journey back to Albuquerque, during which they observed "a great star on fire, racing across the dark sky with a blazing trail". According to historian A.L. Kroeber, "the event sealed the fate of the Mohave as an independent people." In April 1859, the US military established Fort Mohave near the location of the massacre at Beale's Crossing.

References

- Baley 2002, pp. 24–6.

- Baley 2002, p. vii.

- Ricky 1999, p. 100.

- Baley 2002, p. ix.

- Waters 1993, p. 127.

- Bonsal 1912, p. 213.

- Waters 1993, p. 129.

- ^ Baley 2002, pp. 2–3.

- Baley 2002, p. 3.

- Baley 2002, p. 4.

- Baley 2002, pp. 8–11.

- ^ Baley 2002, p. 11.

- Baley 2002, pp. 11–12.

- Baley 2002, p. 5.

- Baley 2002, pp. 5, 15.

- Baley 2002, p. 15.

- Baley 2002, pp. 1–3, 14–15.

- Baley 2002, pp. 13–14.

- Baley 2002, p. 14.

- Baley 2002, pp. 24, 28–37, 39–40.

- Baley 2002, p. 1.

- Baley 2002, pp. 31, 34.

- ^ Baley 2002, p. 26.

- ^ Baley 2002, pp. 29–30.

- Baley 2002, pp. 30–4.

- Baley 2002, pp. 31–2.

- Baley 2002, pp. 5–7, 15–16.

- Baley 2002, p. 35.

- Baley 2002, pp. 35–6.

- ^ Baley 2002, p. 37.

- Baley 2002, pp. 36–7.

- Baley 2002, pp. 38–40.

- Baley 2002, pp. 40–1.

- ^ Baley 2002, p. 41.

- ^ Baley 2002, p. 42.

- Baley 2002, p. 43.

- Baley 2002, pp. 43–4.

- Baley 2002, p. 44.

- Baley 2002, p. 45.

- ^ Baley 2002, p. 46.

- Baley 2002, p. 47.

- Baley 2002, p. 48.

- Baley 2002, pp. 47–8.

- Baley 2002, pp. 48–9.

- ^ Baley 2002, pp. 50–1.

- Baley 2002, pp. 51–3.

- Baley 2002, p. 56.

- Baley 2002, p. 59.

- Baley 2002, pp. 56, 58.

- Baley 2002, p. 61.

- Baley 2002, pp. 61–2.

- ^ Baley 2002, pp. 63–4.

- ^ Kroeber & Kroeber 1973, p. 53.

- Baley 2002, pp. 67–9.

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 130.

- Baley 2002, pp. 70–1.

- Baley 2002, pp. 5, 71.

- Baley 2002, p. 71.

- Zappia 2014, p. 129.

- Baley 2002, p. 72: the distance from their camp to Albuquerque was 500 miles (800 km); Waters 1993, p. 130: "a great star on fire, racing across the dark sky with a blazing trail".

- Waters 1993, p. 131.

Notes

- Beale's Wagon Road would eventually be supplanted by U.S. Route 66 and later, Interstate 40.

- The Mojave Road stretches from where Beale's Wagon Road meets the Colorado River to San Bernardino and Los Angeles, California.

- Both the Baley and Hedgpeth companies also brought small libraries with them.

- In 1832, famed mountain man Jedediah Smith was killed by Comanches while taking the Cimarron Cutoff.

- Unbeknownst to the Rose-Baley Party, Beale was decidedly unsatisfied with Savedra's skills as a guide, and had demoted him to helping with the animals in the pack train. The Rose-Baley Party paid Savedra's fee of $500 in advance.

- The oldest inscription at El Morro National Monument is that of New Mexico's first governor, Juan de Oñate, who marked the rock on April 16, 1605.

- The party was now entering the domain of the Navajo people, who strongly disliked outsiders in their land. Nevertheless, the emigrants did not see any Navajo in the area, as they passed the warmer months of the year in higher country where they could find plentiful grass for their flocks.

- While camped near Canyon Diablo, several members of the Rose-Baley Party, including Gillum Baley and Amanda Rose, carved their names into Register Rock No. 4.

- In addition to the killing of Alpha Brown, the entirety of the seven-member Bentner family were massacred while traveling unaccompanied from Baley's mountain camp to Rose's river camp.

Bibliography

- Baley, Charles W. (2002). Disaster at the Colorado: Beale's Wagon Road and the First Emigrant Party. Utah State University Press. ISBN 978-0874214376.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bonsal, Stephen (1912) . Edward Fitzgerald Beale, a pioneer in the path of empire, 1822-1903. G. P. Putnam's sons. ASIN B003OMEK84.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kroeber, A.L.; Kroeber, C.B. (1973). A Mohave War Reminiscence, 1854-1880. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486281636.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ricky, Donald B. (1999). Indians of Arizona: Past and Present. North American Book Distributors. ISBN 9780403098637.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Waters, Frank (1993). Brave Are My People: Indian Heros Not Forgotten. Clear Light Publishers. ISBN 9780940666214.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zappia, Natale A. (2014). Traders and Raiders: The Indigenous World of the Colorado Basin, 1540-1859. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9781469615851.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)