This is an old revision of this page, as edited by North Shoreman (talk | contribs) at 16:44, 24 March 2015 (Undid revision 653327160 by Getoverpops (talk) -- editing against consensus and ignoring discussion page where there is unanimity against your proposals). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:44, 24 March 2015 by North Shoreman (talk | contribs) (Undid revision 653327160 by Getoverpops (talk) -- editing against consensus and ignoring discussion page where there is unanimity against your proposals)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For the British strategy in the American Revolutionary War, see Southern theater of the American Revolutionary War.

In American politics, the Southern strategy refers to a Republican Party strategy of gaining political support for certain candidates in the Southern United States by appealing to racism against African Americans.

Though the "Solid South" had been a longtime Democratic Party stronghold due to the Democratic Party's defense of slavery before the American Civil War and segregation for a century thereafter, many white Southern Democrats stopped supporting the party following adoption of the civil rights plank of the Democratic campaign in 1948 (against which the Dixiecrats formed), support for the African-American Civil Rights Movement, the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, and desegregation.

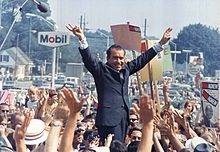

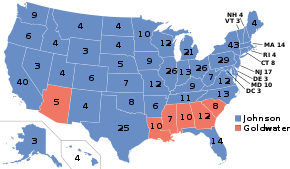

Republican Presidential candidates Richard Nixon and Senator Barry Goldwater worked to attract southern white conservative voters to their candidacies and the Republican Party in the late 1960s. Barry Goldwater won the five formerly Confederate states of the Deep South (Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina) in the 1964 presidential election, but he won in only one other state, Arizona, his home state. In his 1968 campaign for the presidency, Nixon won Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, and Tennessee, all former Confederate states. It contributed to the electoral realignment of some Southern states to the Republican Party. After gaining important federal civil rights legislation with the support of the Democratic Party, including the Voting Rights Act of 1965, more than 90 percent of black voters registered with the Democratic Party. The VRA effectively ended their decades-long disenfranchisement by southern states. As the twentieth century came to a close, the Republican Party began trying to appeal again to black voters, though with little success.

In 2005, Republican National Committee chairman Ken Mehlman formally apologized to the NAACP for exploiting racial polarization to win elections and ignoring the black vote.

Introduction

Although the phrase "Southern strategy" is often attributed to Nixon's political strategist Kevin Phillips, he did not originate it but popularized it. In an interview included in a 1970 New York Times article, he touched on its essence:

- From now on, the Republicans are never going to get more than 10 to 20 percent of the Negro vote and they don't need any more than that...but Republicans would be shortsighted if they weakened enforcement of the Voting Rights Act. The more Negroes who register as Democrats in the South, the sooner the Negrophobe whites will quit the Democrats and become Republicans. That's where the votes are. Without that prodding from the blacks, the whites will backslide into their old comfortable arrangement with the local Democrats.

While Phillips sought to increase Republican power by polarizing ethnic voting in general, and not just to win the white South, the South was by far the biggest prize yielded by his approach. Its success began at the presidential level, gradually trickling down to statewide offices, the Senate, and the House, as some legacy segregationist Democrats retired or switched to the GOP. In addition, the Republican Party worked for years to develop grassroots political organizations across the South, supporting candidates for local school boards and offices, as one example. But, following the Watergate scandal, there was broad support in the South for the Southern Democrat Jimmy Carter in the 1976 election.

From 1948 to 1984 the Southern states, traditionally a stronghold for the Democrats, became key swing states, providing the popular vote margins in the 1960, 1968 and 1976 elections. During this era, several Republican candidates expressed support for states' rights, which some critics claim was a "codeword" of opposition to federal enforcement of civil rights for blacks and intervention on their behalf, including passage of the Voting Rights Act to enforce their ability to exercise the franchise.

19th century disfranchisement and rise of the Solid South

Main article: Solid SouthAfter the American Civil War, southern states gained additional seats in the House of Representatives and representation in the Electoral College because freed slaves were granted full citizenship and suffrage. Southern white resentment stemming from the Civil War and the Republican Party’s policy of Reconstruction kept most southern whites in the Democratic Party, but the Republicans competed in the South with a biracial coalition of freedmen, Unionists and highland whites.

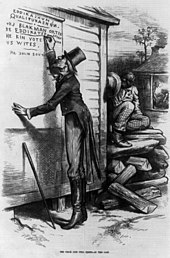

Rising intimidation, election fraud, and violence by white paramilitary groups such as the White League and Red Shirts who supported the Democratic Party during the mid to late-1870s, contributed to the turning out Republican officeholders and suppression of the black vote. After the North agreed to withdraw federal troops under the Compromise of 1877, white Democrats used a variety of tactics to reduce voting by African Americans and poor whites. In the 1880s they began to pass legislation making election processes more complicated.

From 1890 to 1908, the white Democratic legislatures in every Southern state enacted new constitutions or amendments with provisions to disenfranchise most blacks and tens of thousands of poor whites. Provisions required payment of poll taxes, and complicated residency, literacy tests, and other requirements which were subjectively applied against blacks. As blacks lost their vote, the Republican Party lost its ability to effectively compete. There was a dramatic drop in voter turnout as these measures took effect, a drop in participation that continued across the South.

Because blacks were closed out of the political process, the South's congressional delegations and state governments were dominated by white Democrats until past the middle of the 20th century. Effectively, Southern white Democrats controlled all the votes of the expanded population by which Congressional apportionment was figured. Many of their representatives achieved powerful positions of seniority in Congress, giving them control of chairmanships of significant Congressional committees. Although the Fourteenth Amendment has a provision to reduce the Congressional representation of states that denied votes to their adult male citizens, this provision was never enforced. Because African Americans could not be voters, they were also prevented from being jurors and serving in local offices. Services and institutions for them in the segregated South were chronically underfunded by state and local governments.

During this period, Republicans held only a few House seats from the South. Between 1880 and 1904, Republican presidential candidates in the South received between 35 and 40 percent of that section's vote (except in 1892, when the 16 percent for the Populists knocked Republicans down to 25 percent). From 1904 to 1948, Republicans received more than 30 percent of the section's votes only in the 1920 (35.2 percent, carrying Tennessee) and 1928 elections (47.7 percent, carrying five states). The only important political role of the South in presidential elections came in the 1912 election, when it provided the delegates to select Taft over Theodore Roosevelt in that year's Republican convention.

Scholar Richard Valelly credits Woodrow Wilson's election to the disfranchisement of blacks in the South, which resulted in a substantial loss of votes for Republicans. He also documents far-reaching effects in Congress, where the Democratic South gained "about 25 extra seats in Congress for each decade between 1903 and 1953."

During this period, Republicans regularly supported anti-lynching bills, which were filibustered by Southern Democrats in the Senate, and appointed a few blacks to office. In the 1928 election, the Republican candidate Herbert Hoover rode the issues of prohibition and anti-Catholicism to carry five former Confederate states, with 62 of the 126 electoral votes of the section. After his victory, Hoover attempted to build up the Republican Party of the South, transferring his limited patronage away from blacks and toward the same kind of white Protestant businessmen who made up the core of the Northern Republican Party. With the onset of the Great Depression, which severely affected the South, Hoover soon became extremely unpopular. The gains of the Republican Party in the South were lost. In the 1932 election, Hoover received only 18.1 percent of the Southern vote for re-election.

World War II and population changes

In the 1948 election, after Harry Truman signed an Executive Order to desegregate the Army, a group of Southern Democrats known as Dixiecrats split from the Democratic Party in reaction to the inclusion of a civil rights plank in the party's platform. This followed a floor fight led by Minneapolis mayor and (soon-to-be senator) Hubert Humphrey. The disaffected Democrats formed the States' Rights Democratic, or Dixiecrat Party, and nominated Governor Strom Thurmond of South Carolina for president. Thurmond carried four southern states in the general election: Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina. The main plank of the States' Rights Democratic Party was maintaining segregation and Jim Crow in the South. The Dixiecrats, failing to deny the Democrats the presidency in 1948, soon dissolved, but the split lingered. In 1964, Thurmond was one of the first conservative southern Democrats to switch to the Republican Party.

In addition to the splits in the Democratic Party, the population movements associated with World War II had a significant effect in changing the demographics of the South. More than 5 million African Americans migrated from the South to the North and West in the second Great Migration, lasting from 1940-1970. Starting before WWII, many took jobs in the defense industry in California and major industrial cities of the Midwest.

With control of powerful committees, during and after the war, Southern Democrats gained new federal military installations in the South and other investments. Changes in industry, and growth in universities and the military establishment in turn attracted Northern transplants to the South, and bolstered the base of the Republican Party. In the post-war Presidential campaigns, Republicans did best in those fastest-growing states of the South that had the most Northern transplants. In the 1952, 1956 and 1960 elections, Virginia, Tennessee and Florida went Republican, while Louisiana went Republican in 1956, and Texas twice voted for Dwight D. Eisenhower and once for John F. Kennedy. In 1956, Eisenhower received 48.9 percent of the Southern vote, becoming only the second Republican in history (after Ulysses S. Grant) to get a plurality of Southern votes.

The white conservative voters of the states of the Deep South remained loyal to the Democratic Party, which had not officially repudiated segregation. Because of declines in population or smaller rates of growth compared to other states, Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas and North Carolina lost congressional seats from the 1950s to the 1970s, while South Carolina, Louisiana and Georgia remained static.

The "Year of Birmingham" in 1963 highlighted racial issues in Alabama. Through the spring, there were marches and demonstrations to end legal segregation. The Movement's achievements in settlement with the local business class were overshadowed by bombings and murders by the Ku Klux Klan, most notoriously in the deaths of four girls in the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church.

After the Democrat George Wallace was elected as Governor of Alabama, he emphasized the connection between states' rights and segregation, both in speeches and by creating crises to provoke Federal intervention. He opposed integration at the University of Alabama, and collaborated with the Ku Klux Klan in 1963 in disrupting court-ordered integration of public schools in Birmingham.

Many of the states' rights Democrats were attracted to the 1964 presidential campaign of conservative Republican Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona. Goldwater was notably more conservative than previous Republican nominees, such as Dwight D. Eisenhower. Goldwater's principal opponent in the primary election, Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York, was widely seen as representing the more moderate, pro-Civil Rights Act, Northern wing of the party (see Rockefeller Republican, Goldwater Republican).

In the 1964 presidential campaign, Goldwater ran a conservative campaign that broadly opposed strong action by the federal government. Although he had supported all previous federal civil rights legislation, Goldwater decided to oppose the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He believed that this act was an intrusion of the federal government into the affairs of states and, second, that the Act interfered with the rights of private persons to do business, or not, with whomever they chose, even if the choice is based on racial discrimination. (In many instances, southern whites wanted the business of blacks but on their terms, for instance, restricting their use of water fountains, lunch counters, and dressing rooms in department stores.)

Goldwater's position appealed to white Southern Democrats, and Goldwater was the first Republican presidential candidate since Reconstruction to win the electoral votes of the Deep South states (Louisiana, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and South Carolina). Outside the South, Goldwater's negative vote on the Civil Rights Act proved devastating to his campaign; the only other state he won was his home one of Arizona, contributing to his landslide defeat in 1964. A Lyndon B. Johnson ad called "Confessions of a Republican," which ran in the North, associated Goldwater with the Ku Klux Klan. At the same time, Johnson’s campaign in the Deep South publicized Goldwater’s support for pre-1964 civil rights legislation. In the end, Johnson swept the election.

At the time, Goldwater was at odds in his position with most of the prominent members of the Republican Party, dominated by so-called Eastern Establishment and Midwestern Progressives. A higher percentage of the Republican Party supported the Civil Rights Act of 1964 than did the Democratic Party, as they had on all previous Civil Rights legislation. The Southern Democrats mostly opposed their Northern Party mates — and their presidents (Kennedy and Johnson) on civil rights issues.

In some Republican circles, the election after the 1964 Civil Rights Act was termed, "The Great Betrayal". Although some Republicans paid a price with white voters — in some cases losing seats — black voters did not return to the Republican fold. In the re-election of Senator Al Gore Sr. from Middle Tennessee, a majority of the still limited number of black voters in the region cast their votes for a man who had voted against the Civil Rights Act.

Roots of the Southern strategy

Lyndon Johnson was concerned that his endorsement of Civil Rights legislation would endanger his party in the South. In the 1968 election, Richard Nixon saw the cracks in the Solid South as an opportunity to tap into a group of voters who had historically been beyond the reach of the Republican Party. George Wallace had exhibited a strong candidacy in that election, where he garnered 46 electoral votes and nearly 10 million popular votes, attracting mostly southern Democrats away from Hubert Humphrey.

Huey P. Newton, Shirley Chisholm, Andrew Young, and Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts had replaced Martin Luther King Jr. as some of the most prominent black leaders. By this point, King had won the Nobel Peace Prize and founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. His assassination in 1968 was followed by rioting by African Americans in many inner-city areas in major cities throughout the country. King's policy of non-violence had already been challenged by other African-American leaders, such as John Lewis and Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

The notion of Black Power advocated by SNCC leaders captured some of the frustrations of African Americans at the slow process of change in achieving acceptance by whites and integration. The civil rights legislation had raised expectations of African Americans; they began to push for faster change, raising racial tensions. Journalists reporting about the demonstrations against the Vietnam War often featured young people engaging in violence or burning draft cards and American flags. Conservatives were also dismayed about the many young adults engaged in the drug culture and "free love" (sexual promiscuity), in what was called the "hippie" counter-culture. These actions scandalized many Americans and created a concern about law and order.

Nixon's advisers did not appeal directly to voters on issues of white supremacy or racism. White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman noted that Nixon "emphasized that you have to face the fact that the whole problem is really the blacks. The key is to devise a system that recognized this while not appearing to." With the aid of Harry Dent and South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, who had switched to the Republican Party in 1964, Richard Nixon ran his 1968 campaign on states' rights and "law and order." Progressives accused Nixon of pandering to Southern whites, especially with regard to his "states' rights" and "law and order" positions, which were widely taken to symbolize southern resistance to civil rights. This tactic was later described by David Greenberg in Slate as "dog-whistle politics" although Nixon adviser Pat Buchanan disputed this characterization, according to an article in The American Conservative.

The independent candidacy of George Wallace, former Democratic governor of Alabama, partially negated the Southern strategy. With a much more explicit attack on integration and black civil rights, Wallace won all of Goldwater's states (except South Carolina), as well as Arkansas and one of North Carolina's electoral votes. Nixon picked up Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina and Florida, while Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey's only southern state was Texas. Writer Jeffrey Hart, who worked on the Nixon campaign as a speechwriter, says that Nixon did not have a "Southern Strategy" but "Border State Strategy;" as he said that the 1968 campaign ceded the Deep South to George Wallace. He suggested that the press called it a "Southern Strategy" as they are "very lazy".

In the 1972 election, by contrast, Nixon won every state in the Union except Massachusetts, winning more than 70 percent of the popular vote in most of the Deep South (Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina) and 61% of the national vote. He won more than 65 percent of the votes in the other states of the former Confederacy. Nixon won 18% of the black vote nationwide. Despite his appeal to Southern whites, Nixon was widely perceived as a moderate in other states of the union and won those on that basis.

Evolution

As civil rights grew more accepted throughout the nation, basing a general election strategy on appeals to "states' rights," which some would have believed opposed civil rights laws, would have resulted in a national backlash. The concept of "states' rights" was considered by some to be subsumed within a broader meaning than simply a reference to civil rights laws. States rights became seen as encompassing a type of federalism that would prevent Federal intervention in the culture wars.

In 1980, Republican candidate Ronald Reagan's proclaiming "I believe in states' rights" at his first campaign stop at Philadelphia, Mississippi, where three civil rights activists had been lynched in 1964, was cited as evidence that the Republican Party was building upon the Southern strategy again. Reagan launched his campaign at the Neshoba County Fair near Philadelphia, Mississippi, the county where the three civil rights workers were murdered during 1964's Freedom Summer.

In addition to presidential campaigns, Democratic charges of racism have been made about subsequent Republican campaigns for the House of Representatives and Senate in the South. The Willie Horton commercials used by supporters of George H. W. Bush against Michael Dukakis in the election of 1988 were considered by many Democrats, including Jesse Jackson, Lloyd Bentsen, and many newspaper editors, to be racist. The 1990 re-election campaign of Jesse Helms attacked his opponent's alleged support of "racial quotas," most notably through an ad in which a white person's hands are seen crumpling a letter indicating that he was denied a job because of the color of his skin.

Bob Herbert, a New York Times columnist, reported a 1981 interview with Lee Atwater, published in Southern Politics in the 1990s by Alexander P. Lamis, in which Atwater discussed the Southern strategy:

Questioner: But the fact is, isn't it, that Reagan does get to the Wallace voter and to the racist side of the Wallace voter by doing away with legal services, by cutting down on food stamps?

Atwater: You start out in 1954 by saying, "Nigger, nigger, nigger." By 1968 you can't say "nigger" — that hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like forced busing, states' rights and all that stuff. You're getting so abstract now you're talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you're talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is blacks get hurt worse than whites. And subconsciously maybe that is part of it. I'm not saying that. But I'm saying that if it is getting that abstract, and that coded, that we are doing away with the racial problem one way or the other. You follow me — because obviously sitting around saying, "We want to cut this," is much more abstract than even the busing thing, and a hell of a lot more abstract than "Nigger, nigger."

Herbert wrote in the same column, "The truth is that there was very little that was subconscious about the G.O.P.'s relentless appeal to racist whites. Tired of losing elections, it saw an opportunity to renew itself by opening its arms wide to white voters who could never forgive the Democratic Party for its support of civil rights and voting rights for blacks."

In later decades, some analysts made the argument that Southern whites' move to the Republican Party had more to do with economic interests than racism. In The End of Southern Exceptionalism, political scientists Richard Johnston and Byron Shafer argued that Republican dominance in the South was driven by increasing numbers of wealthy suburbanites. Conversely, other scholarship has reaffirmed the role of racial factors: in 2005, Valentino and Sears reported that "the South's shift to the Republican party has been driven to a significant degree by racial conservatism".

Some analysts viewed the 1990s as the apogee of Southernization or the Southern strategy, given that the Democratic president Bill Clinton and vice-president Al Gore were from the South, as were Congressional leaders on both sides of the aisle. During the end of Nixon's presidency, the Senators representing the former Confederate states in the 93rd Congress were primarily Democrats. During the beginning of Bill Clinton's, 20 years later in the 103rd Congress, this was still the case.

Shift in strategy

While running for President, Clinton promised to "end welfare as we have come to know it" while in office. In 1996, Clinton would fulfill his campaign promise and one manifestation of the longtime GOP goal of major welfare reform was passed. After two welfare reform bills sponsored by the GOP-controlled Congress were successfully vetoed by the President, a compromise was eventually reached; Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Actinto law on August 22, 1996. Around this time, the main focus the Southern Strategy had drifted away from race-related campaign issues and shifted towards cultural issues, such as the preservation of religious conservatism in American society.

In the mid-1990s, the Republican Party made major attempts to court African-American voters, believing that the strength of religious values within the African-American community and the growing number of affluent and middle-class African Americans would lead this group increasingly to support Republican candidates. An early example of this shift showed during the 1996 Presidential election, when Republican Presidential nominee Bob Dole chose Jack Kemp as his running mate. The New York Congressman had long advocated for urban revitalization projects, a position to appeal to inner-city blacks. General Colin Powell, an African American who gained national recognition for his role in Operation Desert Storm's success, announced he was a registered Republican.

Though the Republican Party attracted the interests of some African-American voters, the group still remained loyal to the Democratic Party. During his time in office, Clinton connected greatly with the Africans Americans. Born into a poor, Southern working-class family, Clinton life and social-economic status growing up resembled that of many African Americans. Since his youth, Clinton had befriended several African Americans. He was easy about making these friendships public since his time as Governor of Arkansas. In addition to his background, Clinton's policies and decisions to appoint numerous African Americans in his cabinet helped him cement his status among those voters. By the time he left office, Clinton's popularity in the African American community surpassed that of Colin Powell and longtime African American civil rights activist Jesse Jackson, according to polls. His administration strengthened African-American loyalty to the Democratic Party.

21st century

Few African Americans voted for George W. Bush and other national Republican candidates in the 2004 elections, although he attracted a higher percentage of black voters than had any GOP candidate since President Ronald Reagan. Following Bush's re-election, Ken Mehlman, Bush's campaign manager and Chairman of the RNC, held several large meetings in 2005 with African-American business, community, and religious leaders. In his speeches, he apologized for his party's use of the Southern Strategy in the past. When asked about the strategy of using race as an issue to build GOP dominance in the once-Democratic South, Mehlman replied,

"Republican candidates often have prospered by ignoring black voters and even by exploiting racial tensions," and, "by the '70s and into the '80s and '90s, the Democratic Party solidified its gains in the African-American community, and we Republicans did not effectively reach out. Some Republicans gave up on winning the African-American vote, looking the other way or trying to benefit politically from racial polarization. I am here today as the Republican chairman to tell you we were wrong."

Despite this admission, racism in the Republican Party has thrived in the past decade.

Recent comments on Southernization and Southern strategy

In 2005, Republican National Committee chairman Ken Mehlman formally apologized to the NAACP for exploiting racial polarization to win elections and ignoring the black vote. But two days after his address to the NAACP he characterized this as a general strategy, not particularly Southern: "It always interests me when people say it was a Southern strategy. The fact is that folks in the North, the South, the East and the West sometimes did this."

Some commentators considered the decisive victory of Democratic Senator Barack Obama in the 2008 presidential election and subsequent re-election in 2012 to represent the lessened influence of Southernization in national politics:

- Wayne Parent, a political scientist at Louisiana State University, said that "The region’s absence from Mr. Obama’s winning formula means it's becoming distinctly less important,... The South has moved from being the center of the political universe to being an outside player in presidential politics."

- Thomas Schaller, a political scientist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, stated that the Republicans had become "a Southernized party.... They have completely marginalized themselves to a mostly regional party," noting that he believed Southernization was over and that the South was no longer needed to win national elections.

- Merle Black, an expert on the region’s politics at Emory University in Atlanta, said the Republican Party went too far in appealing to the South, alienating voters elsewhere. 'They’ve maxed out on the South,' he said, which has 'limited their appeal in the rest of the country.'"

See also

- Bible Belt

- Conservative Coalition

- Politics of the Southern United States

- Racism in the United States

- Solid South

References

- ^ Herbert, Bob (October 6, 2005). "Impossible, Ridiculous, Repugnant". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Boyd, James (May 17, 1970). "Nixon's Southern strategy: 'It's All in the Charts'" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- Carter, Dan T. From George Wallace to Newt Gingrich: Race in the Conservative Counterrevolution, 1963-1994.

- ^ Branch, Taylor (1999). Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963-65. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 242. ISBN 0-684-80819-6. OCLC 37909869.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Herbert, Bob (November 13, 2007). "Righting Reagan's Wrongs?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Black & Black, Earl & Merle (2003). Rise of the Southern Republicans. Harvard University Press. p. 442.

- Kalk, Bruce H. (2001). "The Goldwater Effect, 1962-1966". The Origin of the Southern Strategy. Lanham, Md. : Lexington Books. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-7391-0242-8.

- ^ Apple, R.W. Jr. (September 19, 1996). "G.O.P. Tries Hard to Win Black Votes, but Recent History Works Against It". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Deep South". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- "Deep South". Synonym.com. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ^ Rondy, John (July 15, 2005). "GOP ignored black vote, chairman says: RNC head apologizes at NAACP meeting". The Boston Globe. Reuters. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Allen, Mike (July 14, 2005). "RNC Chief to Say It Was 'Wrong' to Exploit Racial Conflict for Votes". Washington Post. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- Javits, Jacob K. (October 27, 1963). "To Preserve the Two-Party System". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Phillips, Kevin (1969). The Emerging Republican Majority. New York: Arlington House. ISBN 0-87000-058-6. OCLC 18063.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - George C. Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984, p. 132

- Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War, New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, Paperback, 2007, pp.74-80

- Zinn, Howard (1999). A People's History of the United States. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 205–210, 449. ISBN 0-06-052842-7.

- Perman, Michael (2001). "Introduction". Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2593-X. OCLC 44131788.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - "Turnout for Presidential and Midterm Elections". Politics: Historical Barriers to Voting. University of Texas. Archived from the original on August 1, 2008.

- "Beginnings of black education", The Civil Rights Movement in Virginia. Virginia Historical Society. Retrieved April 12, 2009.

- Richard M. Valelly, The Two Reconstructions: The Struggle for Black Enfranchisement University of Chicago Press, 2009, pp. 146-147

- Dobbs, Ricky Floyd (January 1, 2007). "Continuities in American anti-Catholicism: the Texas Baptist Standard and the coming of the 1960 election". Baptist History and Heritage. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ McWhorter, Diane (2001). Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama, The Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80747-5. OCLC 45376386.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Civil Rights Act of 1964 - CRA - Title VII - Equal Employment Opportunities - 42 US Code Chapter 21". Finduslaw.com. Retrieved January 22, 2012.

- Risen, Clay (March 5, 2006). "How the South was won". (subscription required) The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2007-02-11

- Thomas R. Dye, Louis Schubert, Harmon Zeigler. The Irony of Democracy: An Uncommon Introduction to American Politics, Cengage Learning. 2011

- Ted Van Dyk. "How the Election of 1968 Reshaped the Democratic Party", Wall Street Journal, 2008

- Zinn, Howard (1999) A People's History of the United States New York:HarperCollins, 457-461

- Zinn, Howard (1999) A People's History of the United States New York:HarperCollins, 491

- Robin, Corey (2011). The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Sarah Palin. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 0-19-979393-X.

- Johnson, Thomas A. (August 13, 1968). "Negro Leaders See Bias in Call Of Nixon for 'Law and Order'". The New York Times. p. 27. Retrieved 2008-08-02.(subscription required)

- Greenberg, David (November 20, 2007). "Dog-Whistling Dixie: When Reagan said "states' rights," he was talking about race". Slate. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Nixon in Dixie", The American Conservative magazine

- Childs, Marquis (June 8, 1970). "Wallace's Victory Weakens Nixon's Southern Strategy". The Morning Record.

- Hart, Jeffrey (2006-02-09). The Making of the American Conservative Mind (television). Hanover, New Hampshire: C-SPAN.

- Carter, Dan T. From George Wallace to Newt Gingrich: Race in the Conservative Counterrevolution, 1963-1994.

- White, Jack (December 14, 2002). "Lott, Reagan and Republican Racism". Time. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Kornacki, Steve (February 3, 2011). "The "Southern Strategy," fulfilled". Salon. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Cannon, Lou (2003). Governor Reagan: His Rise to Power, New York: Public Affairs, 477-78.

- Michael Goldfield (1997) The Color of Politics: Race and the Mainspring of American Politics, New York: The New Press, 314.

- Walton, Hanes (1997). African American Power and Politics. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-231-10419-7.

- Helms' "Hands" campaign ad on YouTube

- Lamis, Alexander P. (1999). Southern Politics in the 1990s. Louisiana State University Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-8071-2374-4.

- Risen, Clay (December 10, 2006). "The Myth of 'the Southern Strategy'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Valentino NA, Sears DO (2005). "Old Times There Are Not Forgotten: Race and Partisan Realignment in the Contemporary South" (PDF). American Journal of Political Science. 49: 672–688. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00136.x.

- ^ Nossiter, Adam (November 10, 2008). "For South, a Waning Hold on National Politics". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Vobejda, Barbara (August 22, 1996). "Clinton Signs Welfare Bill Amid Division". Washington Post. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Why blacks love Bill Clinton" - interview with DeWayne Wickham, Salon.com, Suzy Hansen, published February 22, 2002, accessed October 21, 2013.

- ^ African-American voting trends Facts on File.com

- Allen, Mike (July 14, 2005). "RNC Chief to Say It Was 'Wrong' to Exploit Racial Conflict for Votes". Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Benedetto, Richard (July 14, 2005). "GOP: 'We were wrong' to play racial politics". USA Today. Retrieved January 22, 2012.

- Transcript of CNN Late Edition with Wolf Blitzer from July 17, 2005 http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0507/17/le.01.html retrieved 10/14/2013

Further reading

- Aistrup, Joseph A. The Southern Strategy Revisited: Republican Top-Down Advancement in the South, Kentucky Press

- Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, The New Press, New York, 2010 (ISBN 978-1-59558-103-7).

- Applebome, Peter. Dixie Rising: How the South is Shaping American Values, Politics, and Culture (ISBN 0-15-600550-6).

- Black, Earl; Black, Merle. The Rise of Southern Republicans, Harvard University Press

- Boyd, James. "Nixon's Southern strategy 'It's All In the Charts'", New York Times, May 17, 1970

- Buchanan, Patrick J. "The Neocons and Nixon's Southern Strategy", December 2002, Patrick Buchanan Official Website

- Carter, Dan T. From George Wallace to Newt Gingrich: Race in the Conservative Counterrevolution, 1963-1994 (ISBN 0-8071-2366-8)

- Carter, Dan T. The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, The Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of Southern Politics (ISBN 0-8071-2597-0)

- Chappell, David L. A Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion and the Death of Jim Crow (ISBN 0-8078-2819-X)

- Egerton, John. "A Mind to Stay Here: Closing Conference Comments on Southern Exceptionalism", Southern Spaces, 29 November 2006.

- Kruse, Kevin M. White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism (ISBN 0-691-09260-5) by

- Phillips, Kevin. The Emerging Republican Majority (ISBN 0-87000-058-6)

- UPI, "Why The GOP's Southern Strategy Ended", 23 February 2001, at NewsMax