This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Luna Santin (talk | contribs) at 08:55, 1 September 2006 (rv; please see WP:NPOV, WP:V, and WP:NOR. Thanks!). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 08:55, 1 September 2006 by Luna Santin (talk | contribs) (rv; please see WP:NPOV, WP:V, and WP:NOR. Thanks!)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Part of a series on | ||||

| Christianity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

||||

| Theology | ||||

|

||||

| Related topics | ||||

Christianity is a monotheistic religion centered on Jesus of Nazareth, and on his life and teachings as presented in the New Testament. Christians believe Jesus to be the Messiah and God incarnate and thus refer to him as Jesus Christ. With an estimated 2.1 billion adherents in 2001, Christianity is the world's largest religion. It is the predominant religion in the Americas, Europe, Oceania, and large parts of Africa. It is also growing rapidly in Asia, particularly in China and South Korea, northern Africa and the Middle East.

Christianity began in the 1st century as a late Second Temple Jewish sect, and shares many religious texts with Judaism, specifically the Hebrew Bible, and other works, which Christians call the Old Testament (see Judeo-Christian). Like Judaism and Islam, Christianity is considered an Abrahamic religion because of the centrality of Abraham in their shared traditions.

According to the New Testament (11:26 Acts 11:26), "the disciples were first called Christians in Antioch." (Greek Template:Polytonic and variant Template:Polytonic, Strong's G5546). The earliest recorded use of the term Christianity (Greek Template:Polytonic) is by Ignatius of Antioch, such as in his Letter to the Magnesians 10 (68–107).

Christian Divisions

Today there is diversity of doctrines and practices amongst various groups that label themselves as Christian. These groups are sometimes classified under denominations, though for various theological reasons many groups reject this classification system. At other times these groups are described in terms of varying traditions, representing core historical similarities and differences. Christianity may be broadly represented as being divided into three main groupings:

- Roman Catholicism: The Roman Catholic Church, the largest single body, which includes Latin Rite and several Eastern Catholic communities and totals more than 1 billion baptized members.

- Eastern Christianity: Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodox Churches, the Assyrian Church of the East, and others with a combined membership of more than 300 million baptized members.

- Protestantism: Numerous groups such as Anglicans, Lutherans, Reformed/Presbyterians, Evangelical, Charismatic, Baptists, Methodists, Nazarenes, Anabaptists, and Pentecostals. The oldest of these separated from the Roman Catholic Church in the 16th century Protestant Reformation, followed in many cases by further divisions. Worldwide total ranges from 592 to 650 million.

The above groupings are not without exceptions. Some groups called Restorationists, which are historically connected to the Protestant Reformation, do not describe themselves as "reforming" a Christian Church continuously existing from the time of Jesus, but as restoring a Church that was historically lost at some point. Some Protestants identify themselves simply as Christian, or born-again Christian, distancing themselves from the confessional nature of many Protestant communities that emerged during the reformation. Typically, they will refer to themselves as "non-denominational" as they have no affiliation with historic denominations (Methodists, Baptists, Anglicans, etc.) Some of them are "founded" or started by individual pastors or a body of church leaders. Others, particularly among Anglicans and in Neo-Lutheranism, identify themselves as being "both Catholic and Protestant". Lastly, a few small communities employ a name similar to the Roman Catholic Church, such as the Old-Catholics, but are not in communion with the See of Rome.

Other denominations and churches are difficult to group with the above classifications at all. This is due to some differences in basic doctrine with the above groups. These include African indigenous churches with up to 110 million members (estimates vary widely), the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (also called Mormons) with more than 12 million members, Jehovah's Witnesses with approximately 6.6 million members, and the Unity Church, with approximately 2 million members.

Beliefs

Although Christianity has always had a significant diversity of belief, mainstream Christian theology considers certain core doctrines esential to orthodoxy. Mainstream Christians often consider followers of Jesus who disagree with these doctrines to be heterodox, heretical, or outside Christianity altogether.

Jesus

Main article: Jesus

|

Christians identify Jesus as the Messiah. The title Messiah comes from the Hebrew word מָשִׁיחַ (mashiakh) meaning the anointed one, for which the Greek translation is Template:Polytonic (Christos), the source of the English word Christ. Christians believe that as Messiah Jesus was anointed as ruler and saviour of both the Jewish people specifically and of humanity in general. Most Christians hold that Jesus' coming was the fulfilment of Old Testament prophecy and the inauguration of the Kingdom of Heaven. The Christian concept of Messiah differs significantly from the contemporary Jewish concept.

Most Christians believe that Jesus is "true God and true man" (or fully divine and fully human). Jesus is believed to have become fully human in all respects, including mortality, and to have suffered the pains and temptations of mortal man, yet without having sinned. From being true God he was capable of defeating death and rising up to life again, known as the resurrection.

According to Christian Scripture, Jesus was born of Mary, a virgin who had conceived, not by sexual intercourse, but by the power of the Holy Spirit. (See Nativity of Jesus). Little of Jesus' childhood is covered by the Gospels compared to his ministry and especially his last week. The Biblical account of his ministry begins with his baptism, and recounts miracles such as turning water into wine at a marriage at Cana, exorcisms, and healings, and quotes his teachings, such as the Sermon on the Mount. He also appointed apostles.

Most Christians consider the death and resurrection of Jesus the central events of history. According to the Gospels, Jesus and his followers went to Jerusalem for the Passover and he was greeted by a crowd of supporters, an event called the triumphal entry. Later that week, he enjoyed a meal (possibly the Passover Seder) with his disciples before going to pray in the Garden of Gethsemane, where he was arrested by Roman soldiers on behalf of the Sanhedrin and the high priest, Caiaphas. The arrest took place clandestinely at night to avoid a riot, because Jesus was popular with the people at large. Judas Iscariot, one of his apostles, betrayed Jesus by identifying his location for money.

Following the arrest, Jesus was tried by the Sanhedrin, which considered his answers to their questions blasphemous and wished to kill him but lacked legal authority. He was sent to Pontius Pilate, who in turn sent him to Herod Antipas (son of the Herod who tried to kill Jesus as an infant). Initially excited at meeting Jesus, about whom he had heard, Herod ended up mocking Jesus and sent him back to Pilate. Remembering that it was a custom at Passover for the Roman governor to free a prisoner (a custom not recorded outside the Gospels), Pilate offered the crowd a choice between Jesus of Nazareth and an insurrectionist named Barabbas. The crowd chose to have Barabbas freed and Jesus crucified. Pilate washed his hands to display that he claimed himself innocent of the injustice of the decision. Pilate then ordered Jesus to be crucified with a charge placed atop the cross (known as the titulus crucis) which read "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews." Jesus died by late afternoon and was buried by Joseph of Arimathea.

According to the Gospels, Jesus was raised from the dead on the third day after his crucifixion. He appeared to Mary Magdalene, and then appeared to various people in various places over the next forty days. Hours after his resurrection, he appeared to two travellers on the road to Emmaus. To his assembled disciples he showed himself on the evening after his resurrection. During one of these visits, Jesus' disciple Thomas initially doubted the resurrection, but after being invited to place his finger in Jesus' pierced side, said to him, "My Lord and my God!" Before his Ascension Jesus instructed his Apostles to "teach all nations", known as the Great Commission.

Salvation

Main article: SalvationMost Christians believe that salvation from "sin and death" is available through faith in Jesus as savior because of his atoning sacrifice on the cross which paid for sins. Reception of salvation is called justification, which is usually understood as Divine grace, not something that can be earned.

The operation and effects of grace are understood differently by different traditions. Reformed theology goes furthest in teaching complete dependence on grace, by teaching that humanity is completely helpless (Total depravity) and that those who are given this grace invariably put their faith in Christ and are saved (Irresistible grace). (See Five points of Calvinism.) Catholicism, while still teaching dependence on grace, puts more emphasis on free will and the need to cooperate with grace.

Ancient Gnostic Christians stood out for believing that salvation came from divine knowledge, or gnosis, which Jesus had revealed to selected adepts.

The Trinity

Main article: Trinity

Most Christians believe that God is one eternal being who exists as three distinct, eternal, and indivisible persons: the Father, the Son (or Jesus, or the Logos), and the Holy Spirit (or Holy Ghost).

Christianity continued from Judaism a belief in the existence of a single God who created the universe and has divine power over it. Against this background belief in the divinity of Christ developed into the doctrine of the Holy Trinity , which in brief considers that the three persons of God (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) share a single Divine substance. This substance is not considered divided, in the sense that each person has a third of the substance; rather, each person is considered to have the whole substance. The distinction lies in their origins or relations, the Father being unbegotten, the Son begotten, and the Spirit proceeding.

In Reformed theology, the Trinity has special relevance to salvation, which is considered the result of an intra-Trinitarian covenant and in some way the work of each person. The Father elects some to salvation before the foundation of the world, the Son performs the atonement for their sins, and the Spirit regenerates them so they can have faith in Christ, and sanctifies them.

Christians believe the Scriptures were written by the inspiration of the Spirit and that his active participation in a believer's life (even to the extent of "indwelling", or in a certain sense taking up residence within, the believer) is essential to living a Christian life. In Catholic, Orthodox, and some Anglican theology, this indwelling in recieved through the sacrament called Confirmation or, in the East, Chrismation. Pentecostal and Charasmatic Protestants also believe the gift of the Holy Spirit is a distinct experience separate from other experiences like conversion, and some believe it will always be evident through speaking in tongues. Most Protestants believe that the Spirit indwells a new believer at the time of salvation.

The Creeds

Main article: Creed

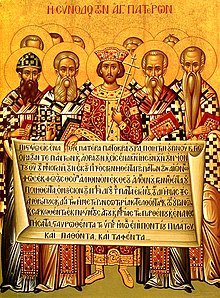

Christianity adopted the practice of drawing up concise statements of belief. These statements, called Creeds, began as baptismal formulas and were later expanded during the Christological controversies of the Fourth and Fifth centuries. The earliest creed still in common use is the Apostles' Creed.

The Nicene Creed, largely a response to Arianism, was formulated at the Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople and ratified as the universal creed of Christendom by the Council of Ephesus in 431. The full text is included here. The phrase "and the son" (presented in brackets below) did not appear in the original creed and is not accepted by the Eastern Orthodox Church.

- We believe in one God, the Father, the Almighty,

- maker of heaven and earth, of all that is seen and unseen.

- We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

- the only Son of God, eternally begotten of the Father,

- God from God, light from light, true God from true God,

- begotten, not made, one in Being with the Father.

- For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven,

- By the power of the Holy Spirit he was born of the Virgin Mary and became man.

- For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate;

- he suffered, died and was buried.

- On the third day he rose again in fulfillment of the Scriptures;

- he ascended into heaven and is seated at the right hand of the Father.

- He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead,

- and his kingdom will have no end.

- We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life,

- who proceeds from the Father

- Who with the Father and the Son is worshiped and glorified.

- Who has spoken through the prophets.

- We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church.

- We acknowledge one baptism for the forgiveness of sins.

- We look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come. Amen.

The Chalcedonian Creed (which is not accepted by the Oriental Orthodox Churches) taught that Christ is one person who has two natures, one divine and one human, and that both natures are complete, and that the two do not mix, but are nevertheless perfectly united into one person. The last point is also known as hypostatic union.

In the Western Church the Athanasian Creed is recieved as having the same status as the Nicene and Chaceldonian. It says: "We worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity; neither confounding the Persons not dividing the Substance."

Most Protestants accept the Creeds. Some Protestant traditions believe Trinitarian doctrine without making use of the Creeds themselves.

Non-Trinitarians

Main article: NontrinitarianismThe earliest non-Trinitarian belief claiming descent from Jesus was Gnosticism, which generally held that the God of the Old Testament was a lower, evil god, while Jesus was an emissary from the higher good god.

Some non-Trinitarians condemn Trinitarian doctrine as an implicit tritheism, though Trinitarians have explicitly denied holding such a view of God and Trinitarian statements of faith from all traditions affirm that there is only one God (e.g., the Nicene Creed, Athanasian Creed, and Chalcedonian Creed; the Protestant confessions; catechisms of both Protestant and Catholic origin).

Ancient examples of this kind of non-Trinitarianism include the Ebionites, Sabellianism, and Arianism, and modern examples include Oneness Pentecostals, Jehovah's Witnesses, and Unitarianism.

Scriptures

Main article: BibleVirtually all Christian churches accept the authority of the Bible, a collection of canonical books in two parts, the Old Testament and the New Testament.

The Old Testament contains the entire Jewish Tanakh. In the Christian canon the books are presented in a different order and some books of the Tanakh are divided into several books by the Christian canon (e.g., the minor prophets are twelve books in the Christian canon but one book called "the Twelve" in the Jewish canon). The Catholic and Orthodox canon includes the Jewish canon and other books called Deuterocanonical, while Protestants classify the latter as Apocrypha.

The first books of the New Testament are the Gospels, which tell of the life and teachings of Jesus. There are four canonical Gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. The first three are often called synoptic because they share much material, while John has more unique material. Ornamental books of the four gospels are sometimes used in church liturgies.

The rest of the New Testament consists of the Acts of the Apostles, a sequel to Luke's Gospel which describes the very early history of the Church; the Pauline epistles and General epistles, which are occasional letters from early Christian leaders to congregations or individuals; and the Book of Revelation, an apocalyptic tract.

Some traditions maintain less mainstream canons. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church maintains two canons, the Narrow Canon, itself larger than any Biblical canon outside Ethiopia, and the Broad Canon, which has even more books. The Latter Day Saints hold three additional books to be the inspired word of God: The Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price.

The Gnostics had numerous books outside of the orthodox canon, for example The Gospel of Thomas.

Interpretation

Though Christians largely agree on the content of the Bible, no such consensus exists on the crucial matter of its interpretation, or exegesis, an issue which dates to ancient times.

The earliest schools of Biblical interpretation were the Alexandrine, and the Antiochene. Alexandrine interpretation, exemplified by Origen, tended to read Scripture allegorically, while Antiochene interpretation insisted on the literal sense, holding that other meanings (called theoria) could only accepted if based on the literal meaning.

Traditional Catholic interpretation admits four senses of Scripture. The literal sense is the plain meaning (which would still take account of figures of speech), so that a reference to David means the historical figure. The allegorical or typological sense teaches Christian doctrine, so that a reference to David may mean Christ. The tropological or moral sense contains ethical teaching, and the anagogical or eschatological sense teaches about the Last Things. The meanings derived from the three non-literal senses may also be stated literally elsewhere.

Protestantism rejects the elevation of other senses to the same level as the literal, although typology remains fairly common in Protestant interpretation.

Last Things

Main article: EschatologyTraditional Christian theology teaches that the soul will continue consciousness after death until the General Resurrection, in which all people who have ever lived will rise from the dead at the end of time, to be judged by Christ when He returns to fulfill the rest of Messianic prophecy.

Christian views of the afterlife generally involve heaven and hell. These realms are thought to be eternal. Catholicism adds the transitory realm of purgatory whose denizens are purified for a period of time before entering into heaven.

Worship and practices

Virtually all Christian traditions affirm that Christian practice should include acts of personal piety such as prayer, Bible reading, and attempting to live a Christ-like lifestyle. This lifestyle includes not only obedience to the Ten Commandments, as interpreted by Christ (as in the Sermon on the Mount), but also love for one's neighbour in both attitude and action — whether friend or enemy, Christian or non-Christian. This love is commanded by Christ and, according to him, is next only in importance to love for God; it includes obedience to such injunctions as "feed the hungry" and "shelter the homeless", both informally and formally. Christianity teaches that it is impossible for people to be completely without sin but that moral and spiritual progress can only occur with God's help through the gift of the Holy Spirit who dwells within all faithful believers. Christians believe that by sharing in Christ's life, death, and resurrection, they die with him to sin and can be resurrected with him to new life.

Orthodox, Catholic, and some Anglican believers describe Christian worship in terms of the seven sacraments. These include baptism, confirmation or Chrismation, the Eucharist (communion), penance and reconciliation, Anointing of the Sick, Holy Orders, and matrimony. Many Protestant groups, following Martin Luther, recognize the sacramental nature of baptism and Eucharist, but not usually the other five in the same way. Anabaptist and Brethren groups would add feet washing. Pentecostal, Charismatic, and Holiness Churches emphasize "gifts of the Spirit" such as spiritual healing, prophecy, exorcism, and speaking in tongues. These emphases are used not as "sacraments" but as means of worship and ministry. The Quakers deny the entire concept of sacraments. Nevertheless, their "testimonies" affirming peace, integrity, equality, and simplicity are affirmed as integral parts of the Quaker belief structure.

Some Protestants tend to view Christian rituals in terms of commemoration apart from mystery. Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Old-Catholic and many Anglican, Lutheran, and Reformed Christians hold the commemoration and mystery of rituals together, seeing no contradiction between them.

Weekly worship services

Justin Martyr (First Apology, chapter LXVII) describes a second-century church service thus:

- And on the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen; and there is a distribution to each, and a participation of that over which thanks have been given, and to those who are absent a portion is sent by the deacons. And they who are well to do, and willing, give what each thinks fit; and what is collected is deposited with the president, who succours the orphans and widows and those who, through sickness or any other cause, are in want, and those who are in bonds and the strangers sojourning among us, and in a word takes care of all who are in need.

Justin's description, which applies to some extent to most church services today, alludes to the following components:

- Scripture readings drawn from the Old Testament, one of the Gospels, or an Epistle. Often these are arranged systematically around an annual cycle, using a book called a lectionary.

- A sermon. In ancient times this followed the scripture readings; today this may occur later in the service, although in liturgical churches the sermon still often follows the readings.

- Congregational prayer and thanksgiving. These will probably occur regularly throughout the service. Justin does not mention this, but some of these are likely to be sung in the form of hymns. The Lord's Prayer is especially likely to be recited.

- The Eucharist (also called Holy Communion, the Sacrament, or the Lord's Supper)—a ritual in which small amounts of bread and wine are consecrated and then consumed. Some Christians believe these represent the body and blood of Christ, whereas Orthodox, Roman Catholics, Lutherans, and many Anglicans believe that they become or are the body and blood of Christ (the doctrine of the Real Presence). Churches in the "liturgical" family (Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and some Anglican) see this as the main part of the service, while some Protestants may celebrate it less frequently. In many cases there are restrictions on who may partake, and visitors should ask about this before attempting to join in. Communion is not generally permitted to non-members in Catholic and Orthodox churches, and some Protestant churches invite visitors to participate only by prior arrangement with the minister. Even members may be subject to restrictions: for example, only Roman Catholics free from unconfessed mortal sin are eligible to receive Communion, though in practice it is rare for the Eucharist to be denied to any Catholic; Orthodox communicants are expected to make confession of sins and fast before communion; and in some Protestant churches, members must give notice to the minister or elders of an intent to take communion. Some denominations substitute grape juice for wine, while the Latter-day Saints use water for their weekly Sacrament.

- A "collection", "offering", or "tithe" in which the people are asked to contribute funds. One common method is to pass a collection plate for contributions. Other methods are more private where donations are given out of the view of others. Christians traditionally use these funds not only for general upkeep of the church, but also for charitable work of various types.

The structure of a service may vary because of special events like baptisms or weddings which are incorporated into the service. In many churches today, children and youth will be excused from the main service in order to attend Sunday school. Many denominations depart from this general pattern in a more fundamental way. For example, the Seventh-day Adventists meet on Saturday (the biblical Sabbath), not Sunday, the day of Christ's resurrection. Charismatic or Pentecostal congregations strive to follow the Holy Spirit and may spontaneously be moved to action rather than follow a formal order of service. At Quaker meetings, participants sit quietly until moved by the Holy Spirit to speak. Some Evangelical services resemble concerts more than liturgy, with rock and pop music, dancing, and use of multimedia. Some denominations do not meet on a weekly basis, but form smaller cell groups within the church which meet weekly at peoples' homes, and gather together fortnightly or monthly for a larger celebration.

In some denominations (mainly liturgical ones) the service is led by a priest. In others (mainly among Protestants) there is a minister, preacher, or pastor. Still others may lack formal leaders, either in principle or by local necessity. A division is often made between "High" church services, characterized by greater solemnity and ritual, and "Low" services, at which a more casual atmosphere prevails even if the service in question is liturgical in nature, but even within these two categories there is great diversity in forms of worship.

In Orthodox churches the congregation traditionally stands throughout the liturgy (although allowances are made for members who are unable to). Many Protestant churches follow a pattern in which participants stand to sing, kneel to pray, and sit to listen (to the sermon). Roman Catholics tend to do the same, though standing for formal prayer is more common. Others services are less programmed and may be quite lively and spontaneous. Music is usually incorporated and often involves a choir and/or organ. Some churches use only a cappella music, either on principle (many Churches of Christ object to the use of musical instruments in worship) or by tradition (as in Orthodoxy).

In many nondenominational Christian churches, as well as many Protestant denominations, there is usually a worship music portion of the service that precedes the sermon or message. This usually consists of the singing of hymns, praise and worship music or psalms. Many churches believe that worship is important as it demonstrates a Christian's love for God and the sacrifice that was made for them.

A recent trend is the growth of "convergence worship", which combines liturgy with spontaneity. This sort of worship is often a result of the influence of charismatic renewal within Churches which are traditionally liturgical. Convergence worship has spawned at least one new denomination, the Charismatic Episcopal Church.

Holidays

Catholics, Eastern Christians, and about half of the Protestants follow a liturgical calendar with various holidays. These calendars include feast days (where special worship services are held, to mark a special anniversary) as well as days of fasting. Typically, a feast will be found preceded by a traditional fast. The Armenian Apostolic church celebrates its Christmas on January 6. The best-known fasting period is Lent.

Even Christians who do not follow a liturgical tradition can generally be found celebrating Christmas and Easter, despite some disagreement as to dates. A few churches object to the recognition of special holidays and may object to the apparent pagan origins of Christmas and Easter.

Symbols

The best-known Christian symbol is the cross, of which many varieties exist. Several denominations tend to favor distinctive crosses: the crucifix for Catholics, the crux orthodoxa for Orthodox, and the unadorned cross for Protestants. However, this is not a hard-and-fast rule. Other Christian symbols include the ichthys ("fish") symbol or, in ancient times, an anchor, as well as the chi-rho. In a modern Roman alphabet, the Chi-Rho appears like a large P with an X overlaid on the lower stem. They are the first two Greek letters of the word Christ - Chi (χ) and Rho (ρ), and the symbol is the one that is said to have appeared to Constantine prior to converting to Christianity (see History and origins section below).

History and origins

Main article: History of Christianity See also: Timeline of Christianity and Early ChristianityChristianity began within the Jewish religion among the followers of Jesus of Nazareth. Under the leadership of the Apostles Peter and Paul, it welcomed Gentiles, and gradually separated from Pharisaic Judaism. Some Jewish Christians rejected this approach and developed into various sects of their own, while others were joined with Gentile Christians in the development of the church; within both groups there existed great diversity of belief. Professor Bentley Layton writes, "the lack of uniformity in ancient Christian scripture in the early period is very striking, and it points to the substantial diversity within the Christian religion." A church hierarchy seems to have developed by the time of the Pastoral Epistles (1 Tim 3, Titus 1) and was certainly formalized by the 4th century .

Christianity spread across the Mediterranean Basin, enduring persecution by the Roman Emperors. As Christianity expanded beyond Israel, it also came into increased contact with Hellenistic culture; Greek philosophy, especially Neoplatonism, became a significant influence on Christian thought through theologians such as Origen. Scholars differ on the extent to which the developing Christian faith adopted identifiably pagan beliefs.

Theological diversity led to disputes about the correct interpretation of Christian teaching and to conflict within and between the local churches. Bishops and local synods condemned some theologians as heretics and defined Church views as orthodoxy (Greek: "the right view"), in contrast to what they deemed heresy (from Greek "faction" or "(wrong) choice"). The most notable heretics were Christian Gnostics. Other early sects deemed heretical included Marcionism, Ebionitism and Montanism. Following Christianity's legalization such disputes intensified. Ecumenical councils, beginning with the Council of Nicaea, called by Constantine in 325, were held to debate theological issues and reach clearer dogmatic definitions, thereby restoring unity.

In the 4th century, after the persecution by Emperor Diocletian, Christianity finally attained legal recognition. His successor Galerius, who had been the instigator of the persecution, issued an edict of toleration on his death-bed in 311, that however had only a temporary effect. In 312, Emperor Constantine, himself newly converted to Christianity, affirmed the religions legal status and went on to give the church a privileged place in society, which it retained apart from a brief pagan interlude 361–363 under Julian the Apostate. In 391 Theodosius I established Nicene Christianity as the official and, except for Judaism, only legal religion of the Roman Empire. From Constantine onwards, the history of Christianity becomes difficult to untangle from the history of Europe (see also Christendom). The Church took over many of the political and cultural roles of the pagan Roman institutions, especially in Europe. The Emperors, seeking unity through the new religion, frequently took part in Church matters, sometimes in concord with the bishops but also against them. Imperial authorities acted to suppress the old pagan cults and groups deemed heretical by the Church, most notably, Arians. The Catholic Encyclopedia notes that "various penal laws were enacted by the Christian emperors against heretics as being guilty of crime against the State. In both the Theodosian and Justinian codes they were styled infamous persons ... In some particularly aggravated cases sentence of death was pronounced upon heretics, though seldom executed in the time of the Christian emperors of Rome."

Various forms of Christian monasticism developed, with the organization of the first monastic communities being attributed to the hermit St Anthony of Egypt around 300. The monastic life spread to many parts of the Christian empire during the 4th and 5th centuries, as many felt that the Christian moral and spiritual life was compromised by the change from a persecuted minority group to an established majority religion, and sought to regain the purity of early faith by fleeing society.

Within the Roman Empire, the Church tightened its administration along Roman lines, creating larger units presided over by Metropolits and Patriarchs. The Council of Nicea recognizes as special the Pope of Rome, the Patriarch of Alexandria and of Antioch, to which later were added the Patriarch of Constantinople (in 381) and the Patriarch of Jerusalem (in 451). This system of five sees was later dubbed the Pentarchy.

The Roman Empire was linguistically divided into the Latin-speaking west, centered in Rome, and the Greek-speaking east, centered in Constantinople. (There were also significant communities in Egypt and Syria.) Outside the Empire, Christianity was adopted in Armenia, Caucasian Iberia (now Georgia), Ethiopia (Aksum), Persia, India, and among the Celtic tribes. Other earlier Christian states included the Ghassanids (from 3rd century) and Osroene.

During the Migration Period, various Germanic peoples adopted Christianity; at first Arianism was widespread (as among Goths and Vandals), but later Roman Catholicism prevailed, beginning with the Franks. The Slavic peoples of Eastern Europe generally adopted Orthodox Christianity, as in the Baptism of Kievan Rus' (988) in Rus' (present-day Russia and Ukraine). Cultural differences and disciplinary disputes finally resulted in the Great Schism (conventionally dated to 1054), which formally divided Christendom into the Catholic west and the Orthodox east.

From the 7th century, Christianity was challenged by Islam, which quickly conquered the Middle East, North Africa, and Spain. Numerous military struggles followed, including the Crusades, the Spanish Reconquista and the eventual conquest of the Byzantine Empire and southeastern Europe by the Turks.

Western Christianity in the Middle Ages was characterized by cooperation and conflict between the secular rulers and the Church under the Pope, and by the development of scholastic theology and philosophy. Later, increasing discontent with corruption and immorality among the clergy resulted in attempts to reform Church and society. The Roman Catholic Church managed to renew itself at the Council of Trent (1545–1563), but only after Martin Luther published his 95 theses in 1517. This was one of the key events of the Protestant Reformation which led to the emergence of Christian denominations. During the following centuries, competition between Catholicism and Protestantism became deeply entangled with political struggles among European states, while many Orthodox Christians found themselves living under Muslim rulers.

Partly from missionary zeal, but also under the impetus of colonial expansion by the European powers, Christianity spread to the Americas, Oceania, East Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. As the European Enlightenment took hold, Christianity was confronted with the discoveries of science (including the heliocentric model and the theory of evolution), and with the development of biblical criticism (linked to the development of Christian Fundamentalism) and modern political ideologies such as Liberalism, Nationalism and Socialism. In the 19th and 20th centuries, important developments have included the rise of Ecumenism and the Charismatic Movement.

(For the contributions of Christianity to the humanities and culture, see Christian philosophy, Christian art, Christian literature, Christian music, Christian architecture.)

Persecution

- Main articles: Persecution of Christians, Historical persecution by Christians

Christians have frequently suffered from persecution. During the first three centuries of its existence, Christianity was regarded with suspicion and frequently persecuted in the Roman Empire. Adherence to Christianity was declared illegal, and, especially in the 3rd century, the government demanded that their subjects (the Jews only excepted) sacrifice to the Emperor as a divinity — a practice that Christianity (along with Judaism) rejected. Persecution in the Roman Empire ended with the Edict of Milan, but it persisted or even intensified in other places, such as Sassanid Persia, and under Islam.

Christians have also been perpetrators of persecution, which has been directed against members of other religions and also against other Christians. Christian mobs, sometimes with government support, have destroyed pagan temples and oppressed adherents of paganism (such as the philosopher Hypatia of Alexandria, who was murdered by a Christian mob). Jewish communities have periodically suffered violence at Christian hands. Christian governments have suppressed or persecuted dissenting Christian denominations, and denominational strife has sometimes escalated into religious wars and inquisitions. Witch hunts, carried out by secular authorities or popular mobs, were a frequent phenomenon in parts of early modern Europe and, to a lesser degree, North America. The degree to which these acts are supported by formal Christian doctrine and scripture is a topic of much debate.

There was some persecution of Christians after the French Revolution during the attempted Dechristianisation of France. State restrictions on Christian practices today are generally associated with those authoritarian governments which either support a majority religion other than Christianity (as in Muslim states), or tolerate only churches under government supervision, sometimes while officially promoting state atheism (as in North Korea). For example, the People's Republic of China allows only government-regulated churches and has regularly suppressed house churches or underground Catholics. The public practice of Christianity is outlawed in Saudi Arabia. On a smaller scale, Greek and Russian governmental restrictions on non-Orthodox religious activity occur today.

Some people cite anti-abortion violence in the United States and the ongoing "troubles" in Northern Ireland as examples of "persecution by Christians" , despite the frequent condemnation of such activities by the vast majority of Christians. Complaints of discrimination have also been made of and by Christians in various other contexts. In other parts of the world, there are persecution of Christians by dominant religious groups or political groups. Many Christians are threatened, discriminated, jailed, or even killed for their faith.

Controversies and criticisms

- See also: Criticism of Christianity

There are many controversies surrounding Christianity as to its influences and history.

- Some claim that Jesus of Nazareth may never have existed, arguing a lack of sources outside the New Testament and sometimes alleged similarities with pre-Christian cult figures (see Jesus as myth). This view has not found general acceptance among historians or Bible scholars (see Historicity of Jesus).

- Some argue that, because Christianity contains similarities to various mystery religions, especially in relation to myths about a god or other figure who is said to have been killed and risen again, these may somehow have been an inspiration for Christianity. For example, Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge compared Christianity to the cult of Osiris. In some cases, initiates in a mystery religion are said to have shared in the god's death, and in his immortality through his resurrection.

- Some scholars consider Paul rather than Jesus as the founding figure of Christianity, pointing to the extent of his writings and the scope of his missionary work.

- Jews believe that followers of Christianity misinterpret passages from the Old Testament, or Tanakh. For example, adherents to Judaism believe that the reference to the coming Messiah in Daniel 9:25 was actually a reference to Cyrus the Great who decreed the building of the Second Temple.

- Many Muslims believe that the Christian Trinity is incompatible with monotheism, even if it is not necessarily tritheistic.

- Missionary work has sometimes been considered a form of cultural imperialism, depending on the motivation and attitude of the missionary.

See also

History and denominations

- Christian theological controversy

- Eastern Christianity portal

- Great Schism

- List of Christian denominations

- Social Gospel

Notes

- http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10499a.htm "Monotheism", The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume X Copyright © 1911 by Robert Appleton Company Online Edition Copyright © 2003 by K. Knight; "From the Stone Age to Christianity: Monotheism and the Historical Process" 2nd edition, Albright, William F., 1957; "Radical Monotheism and Western Culture", Niebuhr, H. Richard, (1960); http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/monotheisticreligions/ Monotheistic Religion resources, ©2006 About, Inc., A part of The New York Times Company. All rights reserved; "God Against the Gods: The History of the War Between Monotheism and Polytheism", Jonathan Kirsch, 2004; http://www.cambridge.org/uk/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=052178655X&ss=exc "An Introduction to Christianity", Linda Woodhead, 2004; http://www.infoplease.com/ce6/society/A0833762.html Monotheism, The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th ed. Copyright © 2006, Columbia University Press. All rights reserved.; http://www.bartleby.com/59/5/monotheism.html "monotheism", The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy Third Edition, Hirsch, Jr., Joseph F. Kett, James Trefil, Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002 ; http://www.ntwrightpage.com/Wright_NDCT_Paul.htm "New Dictionary of Theology", "Paul", David F. Wright, Sinclair B. Ferguson, J.I. Packer, pg. 496–99 ; Meconi, David Vincent "Pagan Monotheism in Late Antiquity (review)" Journal of Early Christian Studies - Volume 8, Number 1, Spring 2000, pp. 111–12

- Princeton University. "Christianity" at Dictionary.com, Christianity, WordNet ® 2.0, Princeton University, retrieved May 18, 2006.

- ^ Religions by Adherents Adherents.com.

- Growth of Christianity in China: WorthyNews.com, AmityNewsService.org; Growth in South Korea: LutherProductions.com, Xhist.com; Growth in northern Africa: FaithFreedom.org ; Niall Ferguson (2005). Colossus:The Rise and Fall of the American Empire. Penguin Books. pp. p. 22. ISBN 0-14-101700-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Acts: 3:1 Acts 3:1; 5:27–42 Acts 5:27–42; 21:18–26 Acts 21:18–26; 24:5 Acts 24:5; 24:14 Acts 24:14; 28:22 Acts 28:22; Romans: 1:16 Romans 1:16; Tacitus Annales xv 44; Flavius Josephus Antiquities xviii 3; Chambers, Mortimer (1974). "5". The Western Experience Volume II:The Early Modern Period (1st ed.). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0-394-31734-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion, editors in chief R. J. Zwi Werblowsky and G. Wigoder (published OUP New York, 1997; ISBN 0-19-508605-8), page 158. - Walter Bauer, Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 2ed., 1979

- Christianity (2005) Adherents.com.

- Witness Membership 2005.

- http://www.adherents.com/Na/Na_653.html

- "Moshiach: The Messiah". Retrieved August 26, 2006.

- Romans 6:23, Ephesians 2:8-9

- "Westminster Confession, Ch. X". Retrieved May 29, 2006.; Spurgeon, Charles. "A defense of Calvinism". Retrieved May 29, 2006.

- "Grace and Justification". Catechism of the Catholic Church. October 11, 1992. Retrieved May 29, 2006.

- ^ "Gnostics, Gnostic Gospels, & Gnosticism". Retrieved May 30, 2006.; J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines (Prince Press, 2004), pp. 22-28.

- J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines (Prince Press, 2004), pp. 87-90; T. Desmond Alexander, Brian S. Rosner, D. A. Carson, Graeme Goldsworthy, New Dictionary of Biblical Theology (InterVarsity Press, 2000), pp. 514-515; Alister E. McGrath, Historical Theology (Blackwell, 2000 edt.), p. 61.

- Lossky, Vladimir. "God in Trinity". Retrieved May 29, 2006.; Boettner, Loraine. "One Substance, Three Persons". Retrieved May 29, 2006.

- Hendryx, John. "The Work of the Trinity in Monergism". Retrieved May 29, 2006.

- 2 Timothy 3:16, 2 Peter 1:21,

"Sacred Scripture". Catechism of the Catholic Church. October 11, 1992. Retrieved August 26, 2006.;

"Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy". October, 1978. Retrieved August 26, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - John 16:7-14, 1 Corinthians 2:10ff

- Text taken from the translation by the Consultation on Common Texts.

- E.g., The Southern Baptist Convention gives no official status to any of the ancient creeds, but the Baptist Faith and Message says:

- The eternal triune God reveals Himself to us as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, with distinct personal attributes, but without division of nature, essence, or being.

- Kelly James Clark. "Trinity or Tritheism" (pdf), Virtual Library of Christian Philosophy, Philosophy Department, Calvin College, retrieved May 18, 2006; Donald K. McKim, ed., Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms (John Knox Press, 1996), p. 288: "tritheism (Lat. "three gods"): Belief in three separate and individual gods. Some early formulations by Christian theologians were considered to move in this direction. Early Christian apologists sought to defend the faith from charges of belief in three gods."

- J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines (Prince Press, 2004), pp. 69-78.

- See, e.g., Aquinas, the Summa Theologicum, Suplementum Tertiae Partis, questions 69 through 99; and Calvin, the Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book Three, Ch. 25.

- The name given by the Greeks or Romans, probably in reproach, to the followers of Jesus. It was first used at Antioch. The names by which the disciples were known among themselves were "brethren," "the faithful," "elect," "saints," and "believers". But as distinguishing them from the multitude without, the name "Christian" came into use, and was universally accepted. This name occurs but three times in the New Testament (Acts 11:26; 26:28; 1 Pet. 4:16). Source: Easton's 1897 Bible Dictionary

- See the canons of the Council of Nicaea, especially canon 6.

- Pagan context (Christianity) Religionfacts.com. URL accessed on July 3 2006.

- Catholic Encyclopedia

- Chambers, Mortimer (1974). "21". The Western Experience Volume II:The Early Modern Period (1st ed.). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0-394-31734-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Budge, E. A. Wallis (1900). Egyptian Religion. Kessinger.

- (Latourette p. 394)

- http://experts.about.com/q/Orthodox-Judaism-952/Daniel-9.htm

- Miller, Dr. Gary, A concise reply to Christianity.

References and select bibliography

|

Further reading

- ReligionFacts.com: Christianity Fast facts, glossary, timeline, history, beliefs, texts, holidays, symbols, people, etc.

- From Jesus to Christianity An objective outlook on Jesus and early Christianity from the world of acadamia. Participating correspondents include professors from Yale, Harvard, Princeton, Duke, Brown, Depaul, and Boston University.

- bethinking.org Christianity Treating Christianity as a whole worldview or perspective and looking at the relationship between historic Christianity and contemporary thought

- Asia is becoming one of the largest Christian populations in the world in the next 30 years.

- "Christianity". Religion & Ethics. BBC. Retrieved 2006-04-12.

- The Bible And Christianity - The Historical Origins - An essay by Scott Bidstrup.

External links

- Christianity Today

- Bible Gateway The Bible online.

- Faith Freedom International

- ReligionFacts.com: Christianity Fast facts, glossary, timeline, history, beliefs, texts, holidays, symbols, people, etc.

- WikiChristian, a wiki book on Christianity, church history and doctrine, and Christian art and music

- Cathar Interpretation of Christianity, a Gnostic view of Christian teachings.

- What is Christianity? summary of Christian beliefs and practices.

- MessageOfJesus.co.uk Christian teachings explained with the aid of classic quotations.

- Syriac Orthodox Resources Large compendium of information and links relating to Oriental Orthodoxy.

- WeSpreadtheWordA directory of christian apologetics, beliefs, history and more

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: