This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Gareth Green (talk | contribs) at 16:31, 22 September 2006 (I added some further comments in relation to transfer pricing in a tax context). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:31, 22 September 2006 by Gareth Green (talk | contribs) (I added some further comments in relation to transfer pricing in a tax context)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Transfer pricing refers to the pricing of goods and services within a multi-divisional organization. Goods from the production division may be sold to the marketing division, or goods from a parent company may be sold to a foreign subsidiary. The choice of the transfer prices affects the division of the total profit among the parts of the company. The discussion below explains the economic theory, but in practice a great many factors influence the transfer prices that are used by multinationals, including performance measurement, capabilities of accounting systems, import quotas, customs duties, VAT, taxes on profits, and (in many cases) simple lack of attention to the pricing. In relation to taxes on profits, it can be advantageous to choose prices such that, in terms of bookkeeping, most of the profit is made in a country with low taxes, and the term "transfer pricing" is sometimes used (incorrectly) as a pejorative term meaning the deliberate shifting of profits to reduce overall taxes paid. However, most countries have tax laws and regulations that limit how transfer prices can be set and ensure that that country gets to tax its "fair" share. Most countries adhere to the arm's length principle as defined in the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations. In the U.S. the pricing of transactions between related parties that are reported for tax purposes are governed by Section 482 of the Internal Revenue Code and the regulations thereunder.

This is perhaps the biggest tax issue facing multinationals, as illustrated by the announcement by GlaxoSmithKline on September 11th, 2006, that they had settled a long-running transfer pricing dispute with the US tax authorities, which will cost them $5.2 billion (the IRS were seeking $15 billion). It is understood that this will be double taxation (that is, GSK will pay UK and US taxes on the same profits).

From marginal price determination theory, we know that generally the optimum level of output is that where marginal costs equals marginal revenue. That is to say, a firm should expand its output as long as the marginal revenue from additional sales is greater than their marginal costs. In the diagram that follows, this intersection is represented by point A, which will yield a price of P*, given the demand at point B.

When a firm is selling some of its product to itself, and only to itself (ie.: there is no external market for that particular transfer good), then the picture gets more complicated, but the outcome remains the same. The demand curve remains the same. The optimum price and quantity remain the same. But marginal cost of production can be separated from the firms total marginal costs. Likewise, the marginal revenue associated with the production division can be separated from the marginal revenue for the total firm. This is referred to as the Net Marginal Revenue in production (NMR), and is calculated as the marginal revenue from the firm minus the marginal costs of distribution.

Transfer Pricing with No External Market

It can be shown algebraically that the intersection of the firms marginal cost curve and marginal revenue curve (point A) must occur at the same quantity as the intersection of the production divisions marginal cost curve with the net marginal revenue from production (point C).

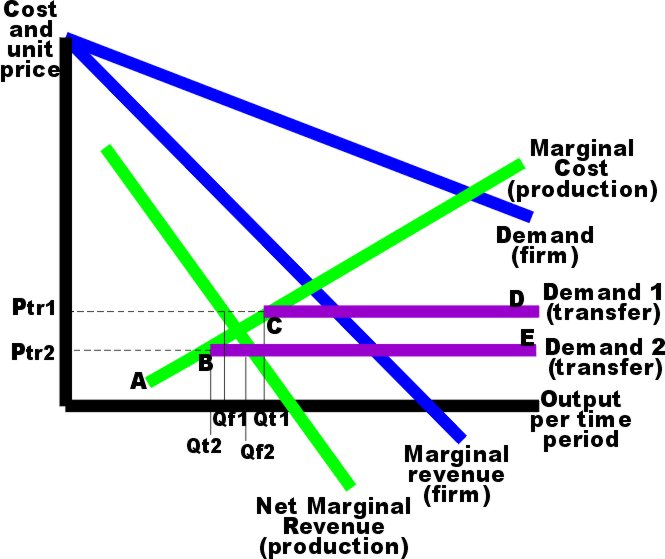

If the production division is able to sell the transfer good in a competitive market (as well as internally), then again both must operate where their marginal costs equal their marginal revenue, for profit maximization. Because the external market is competitive, the firm is a price taker and must accept the transfer price determined by market forces (their marginal revenue from transfer and demand for transfer products becomes the transfer price). If the market price is relatively high (as in Ptr1 in the next diagram), then the firm will experience an internal surplus (excess internal supply) equal to the amount Qt1 minus Qf1. The actual marginal cost curve is defined by points A,C,D.

Transfer Pricing with a Competitive External Market

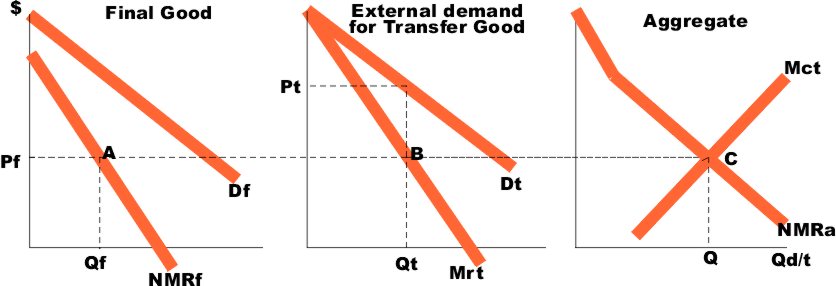

If the firm is able to sell its transfer goods in an imperfect market, then it need not be a price taker. There are two markets each with its own price (Pf and Pt in the next diagram). The aggregate market is constructed from the first two. That is, point C is a horizontal summation of points A and B (and likewise for all other points on the Net Marginal Revenue curve (NMRa)). The total optimum quantity (Q) is the sum of Qf plus Qt.

Transfer Pricing with an Imperfect External Market