This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Jenhawk777 (talk | contribs) at 03:43, 13 September 2018 (→Ethical themes). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 03:43, 13 September 2018 by Jenhawk777 (talk | contribs) (→Ethical themes)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Ideas concerning right and wrong actions that exist in the Hebrew and Christian Bibles| Part of a series on the | |||

| Bible | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

|

|||

|

|||

Biblical studies

|

|||

| Interpretation | |||

| Perspectives | |||

|

Outline of Bible-related topics | |||

| This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Jenhawk777 (talk | contribs) 6 years ago. (Update timer) |

Ethics in the Bible refers to the interpretation of morals in the Hebrew and Christian Bibles. Also called biblical ethics, it comprises a narrow part of the larger fields of Jewish and Christian ethics, which are themselves parts of the larger field of philosophical ethics. Ethics in the Bible is unlike other western ethical theories in that it is seldom overtly philosophical. It presents neither a systematic nor a formal deductive ethical argument. Instead, the Bible provides patterns of moral reasoning that focus on conduct and character in what is sometimes referred to as virtue ethics. This moral reasoning is part of a broad, normative covenantal tradition where duty and virtue are inextricably tied together in a mutually reinforcing manner.

Ethics in the Bible are religious ethics of relationship, with God, others, and the world, as seen through the characteristics of that relationship. The biblical narratives, laws, wisdom sayings, and parables provide the foundations for the ethical concepts and give those ethics their impetus. These biblical foundations are central to, and inseparable from, the Bible's ethical teachings. For example, being created in the image of God provides the impulse for the biblical ethic of human worth and dignity; the universe as good provides the biblical premise for environmental responsibility, and so on.

Ethics in the Bible embraces all areas of human life, including politics, war, peace, criminal justice, human value, relationships, economics, and more.

Critics of ethics in the Bible have called it immoral in some of its teachings. Examples of the church's failures to live up to its own ethic, along with the problem of evil, are also frequently cited as criticisms of biblical ethics.

Overview

Ethicist David W. Jones writes that ethics and morality are not strictly synonymous. Ethics is the study of morals, therefore, biblical ethics is the study and interpretation of those morals, as they are exactly, in the Bible. Bible scholar Alan Mittleman goes on to explain the Bible contains no overtly philosphical ethical theory. Instead, it uses legal texts, wise sayings, parables, and narratives, to offer rather than argue, a moral vision that is suggestive and case-based. This leaves the reader to engage intellectually with moral reasoning of their own.

Theologian John Murray writes "It is impossible to separate the Biblical ethic from the teaching of Scripture..." Throughout the Hebrew Bible there are commands relating to persons, and to worship and ritual, with many commandments remarkable in their blending of the two roles. For example, observance of Shabbat is couched in terms of recognizing God's sovereignty and creation of the world, while also being presented as a social-justice measure to prevent overworking one's employees, slaves, and animals. The Bible consistently binds worship of the Divine to ethical actions, and ethical actions with worship of the Divine. A biblical ethic, then, is a distinctly religious ethic.

Murray argues that God works through humans in history; therefore, he says, it is not God that changes, it is human understanding that is progressive. He adds that, if this thesis is correct, it lends support to the position there is basic agreement on the underlying norms and standards of the Old and the New Testaments.

Sociologist Stephen Mott says ethics in the Bible is a corporate, community based ethic. It is not simply individual. Theologian Robin Gill agrees that "ethics refers to interpretations of, and ideals and norms for, moral behavior at both the individual and societal level."

Biblical foundations

Creation and its ethical implications

Theologian Matthew D. Lundberg writes that key themes of biblical ethics are rooted in the Bible's portrayal of God as creator, sole maker, and ruler, of all reality (Genesis 1-2). This foundational concept runs throughout the biblical canon from Genesis to Revelation and influences several specific ethical principles.

Violence

In 1895 Hermann Gunkel observed that most ancient Near Eastern creation myths contain a theogony depicting a god doing combat with other gods thus including violence as normative in the founding of their cultures. One example is the Babylonian creation epic Enûma Eliš wherein the first step of creation has Marduk fighting and killing Tiamat, a chaos monster, to establish order. Theologian Christopher Hays says Hebrew creation stories are different, they use a term for dividing the "waters" at creation (bâdal which means to separate, make distinct) that is an abstract concept more reminiscent of a Mesopotamian tradition using non-violence at creation. Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann says the Genesis creation story communicates that "God's characteristic action is to "speak"... God "calls the world into being"... The way of God with his world is the way of language."

Old Testament scholar Jerome Creach says the placement of the Genesis (1:1–2:4a) story at the beginning of the entire Bible shows it was normative for those who gave the Old Testament canon its present shape, thereby superseding any other Hebrew creation stories. This is of considerable importance ethically and underlies the Bible's portrayal of human violence as contrary to God's approved method and will for humankind. There are five main lines of response to violence in the Bible: (1) certain acts (i.e. murder) are prohibited by law and punishable accordingly; (2) violence is limited and contained by society and culture (i.e. lex taliones); (3) violence is met with counter-force (Philistines, Armageddon); (4) violence is replaced by creative alternatives (Gideon's candles, clay pots and trumpets in Judges 7); (5) violence is absorbed with patient suffering and forgiveness (turn the other cheek).

Nature

The first Genesis creation account is clear in its assessment of the high value, worth and dignity of the created order. In the first 31 verses of Genesis, the author writes that creation is "good" 6 times. Within the creation accounts is the assumption it is humankind's responsibility to keep God's creation "good" giving the biblical foundation for environmental ethics.

Image of God, Nature of Man

Few ideas are as central to ethics in the Bible as the concept of being created in the image of God. Found in Genesis 1:26–27, it says, in part: "God created mankind in His own image;... male and female He created them." Bible scholar Christopher Marshall says early Rabbis wondered why this story is written in individual terms. They concluded its purpose is to teach the value of the individual, that each person bears the image of God equally, and that each, therefore, is of supreme value. The Rabbis added that, because every human has a common ancestor, there is a fundamental equality always present. The "image" is rarely interpreted as physical likeness but is often interpreted as man's ability to reason, most particularly, to reason morally. Christian ethicist David P. Gushee adds that "The justice teachings of Jesus are closely related to a commitment to life's sanctity..." The ethic of human rights grew from these concepts.

Nico Vorster says the imageo Dei is a relational concept that provides a hierarchy of power as well as biological meaning. Alan Mittleman writes that, within rabbinic Judaism, this means even God must give reasons for what He does. "Authority, whether divine or human, requires the giving of reasons. Political authority, so to speak, relies on epistemic authority. Pure power is never enough. It must be transformed into legitimate authority able to give an account of its own normative claims." For example, the pre-Sinaitic commandment proscribing murder (Genesis 9:6a) ends with the justification: "For in His image did God make man" (Genesis 9:6b). Theologian Nico Vorster writes that bearing the "image of God" means human beings must act responsibly, morally and ethically, in a way that mirrors divine responsibility.

The imageo Dei, combined with mankind's subsequent fall from grace, lay the foundation of the biblical view of the nature of man. Anthony Hoekema writes the image of God is only used to describe humans, therefore it indicates what is unique about man. The Hebrew words tselem and demūth mean likeness in the way a mirror reflects a likeness: only in man does God become visible.Template:Rp67 The second of the Ten Commandments says no graven images of God because God has already made an image of himself by making mankind. More than just spiritual and moral integrity, "Man is a being whose entire constitution images and reflects God." The general theological consensus is that sin does not destroy the image of God in man, but it does distort it.

In order to properly understand the nature of man, Shawn Ritenour writes that there must also be some understanding of the nature of the God. First, Rittenour says the Bible tells us God thinks, and He thinks rationally; (Isaiah 1:18; 55:8-10; Jeremiah 29:11). God knows things. He plans, and lastly, God acts on His plans. The Bible describes God's actions within a framework of choice which means God acts with purpose. Man too is capable of purposeful behavior. Because we are created in the imageo Dei we have the ability to perceive creation and its regularities, reason through what we observe, make plans, and act with purpose. Because God is orderly and because we are created in His image, we also have the ability to think rationally, to learn and know things, to plan and make choices, and can act with purposes we determine for ourselves. This is our nature.

Natural law

According to John Rogerson "to the extent that some Old Testament laws have close parallels with, for example, the laws of Hammurabi, it can be said that The Old Testament acknowledges and draws upon a 'natural morality'". In the Bible, natural law derives moral values from aspects of human nature. The significance and range of ethical naturalism in the Bible addresses what constitutes the best life for human beings as well as what is the best ordering of society.

Gender

According to Near Eastern scholar Carol Meyers, the story of Adam and Eve, "Perhaps more than any other part of the Bible, has influenced western notions of gender and identity." There is controversy and disparity of views concerning ethics in the Bible that deal with women. The iconic role of Eve has been used to support both patriarchal views of women's 'place' in the desired order, and egalitarian views of women and their human nature. Sociologist Linda L. Lindsey says: "Eve's creation from Adam's rib, second in order, with God's "curse" at the expulsion is a stubbornly persistent frame used to justify male supremacy." Yet textual critic Phyllis Trible and Hebrew Bible scholar Tikva Frymer-Kensky say they find the story of Eve in Genesis implies no inferiority of Eve to Adam; the word helpmate (ezer) connotes a mentor in the Bible rather than an assistant and is used frequently for the relation of God to Israel (not Israel to God). Trible points out that, in mythology, the last-created thing is traditionally the culmination of creation, which is implied in Genesis 1 where man is created after everything else—except Eve. However, New Testament scholar Craig Blomberg says ancient Jews might have seen the order of creation in terms of the laws of primogeniture (both in their scriptures and in surrounding cultures) and interpreted Adam being created first as a sign of privilege.

Conscience

Bioethicist James F. Keenan says there are four verses in the New Testament that give the biblical ethic concerning conscience its shape: (1) Romans 2:14-15, where Paul explains every human being has a conscience, even unbelievers, who can be excused from the consequences of ignorant unbelief through a clear conscience; (2) 1 Timothy 4:1,2, which references the self-destructive searing off of the conscience of those who repeatedly willfully violate their own inner moral voice; (3) Hebrews 9:14 in which the author describes the cleansing effect of faith on a conscience burdened with guilt; and (4) 1 Corinthians 8-10, which contains the longest discussion of conscience in the Bible. There Paul lays out the ethic of obligation to the morally weak, where the morally strong have freedom, but willingly limit that freedom due to an understanding of communal responsibility. Keenan writes that the biblical call to act in conscience is a call to act justly and responsibly, and to govern ourselves wisely. Keenan adds that the biblical ethic of conscience says that acting according to conscience is not wrong, even when it turns out we were wrong. He goes on to quote Thomas Aquinas' teaching: "better to die excommunicated than violate our conscience." Mittleman writes: "Despite its modern reputation, the Bible is not simply a record of blunt divine commands. It does not simply assert and command; it invites the engagement of our reason." It often appeals to our intellect and conscience. For example, in Isaiah 1:18, the mode of discourse is that of a lawsuit where those involved can rise above their passions and seek a reasonable solution.

Covenant and tradition

Christopher Marshal writes that covenant is the driving force behind the narrative of the Bible. There are different kinds of covenant in the Bible: conditional and unconditional, promissory, Law, inclusive covenants for the whole human race, and special covenants for a limited group. Irving Greenberg writes that universal covenant pre-exists special covenant in the Bible, and one does not supersede the other. In all cases, covenant is a formal agreement between interested parties that imposes certain moral obligations. Bible scholar Daniel J. Harrington writes the biblical covenant was based on the dynamics of ancient Near Eastern treaties.

The covenant tradition has given rise to several important ethical principles including the right to life. Under covenant law, this right was not the absolute right of secular theory, but was instead limited by the responsibilities of covenant membership. Marshall says there are about 20 offenses that carry the death penalty under Mosaic Law. Within the context of covenant, capitol punishment was not seen as simply a punishment for wrong doing. Its primary purpose was seen by the covenant community as protecting the community. It was believed the covenant community suffered ritual pollution from certain sins. Evans explains that contemporary standards tend to view these laws of capitol punishment as cavalier toward human life, however, within the framework of ancient covenant, it suggests the right to life was communal as well as individual. Israel's 'special covenant' generated an ethic of human rights, as well, in cases such as laws concerning the treatment of slaves. However, many laws of ancient Israel fall below the standards of modern human rights and lack universality. Marshall concludes these early laws, therefore, cannot be seen as intended for the whole human race. Daniel Harrington adds that, the concept of covenant that is so prominent in the Old Testament, can be taken as a theological assumption in the New.

Redemption

See also: Abrogation of Old Covenant laws, Christian views on the Old Covenant, Christian ethics, and Paul the Apostle and JudaismHebrew Bible scholar Jeremiah Unterman writes that redemption in the Hebrew Bible is both a technical legal term and an eschatological concept. The Hebrew verbs ga'al and padah generally refer to the rescue of an individual or an individual's property from debt or debt-servitude but are also used to describe God's rescue of Israel from bondage in Egypt. The words for redemption are also used for the concept of restoration. Thirty-five of thirty-six mentions of future restoration, using the words for redemption, appear in the Hebrew prophets. Both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament see redemption as a divine act. Ethically this has produced a commitment to the value of repentance, moral and ritual purity, and a belief in hope. The promises of redemption, Unterman writes, became an aspect of the Jewish people's perception of the future. He explains "That hope, and those ancient prophecies of redemption, would be adopted and reinterpreted to become the basis of a new religion, Christianity. ... Thus the prophetic hope for redemption would become one of the most important influences of the Jewish Bible on the history of western civilization."

Law and grace

The main dispute of the Council of Jerusalem, whether non-Jewish converts to Christianity should be considered bound to the Old Testament laws, is addressed elsewhere in the New Testament, e.g. regarding dietary laws:

"Don't you perceive that whatever goes into the man from outside can't defile him, because it doesn't go into his heart, but into his stomach, then into the latrine, thus making all foods clean?"

— Mark 7:18. (See also Mark 7)

or regarding divorce:

"I tell you that whoever puts away his wife, except for the cause of sexual immorality, makes her an adulteress; and whoever marries her when she is put away commits adultery."

— Matthew 5:31. (See also Mark 5)

The central teachings of Jesus are presented in the Sermon on the Mount, notably the "golden rule" and the prescription to "love your enemies" and "turn the other cheek".

"You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.' But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you."

— Matthew 5:43–44

Elsewhere in the New Testament (for example, the "Farewell Discourses" of John 14 through 16) Jesus elaborates on what has become known the commandment of love, repeated and elaborated upon in the epistles of Paul (1 Corinthians 13 etc.), see also The Law of Christ and The New Commandment.

Ethical themes in the Bible

Main article: 613 MitzvotPolitical ethics

See also: Political ethicsPolitical theorist Michael Walzer says "the Bible is, above all, a religious book, but it is also a political book." There is no political theory, as such, in the Bible, however, the Bible does contain "legal codes, rules for war and peace, ideas about justice and obligation, social criticism, visions of the good society, and accounts of exile and dispossession." Therefore, it is possible to work out a comparative politics. He goes on to say politics in the Bible is similar to modern "consent theory" which requires agreement between the governed and the authority based on full knowledge and the possibility of refusal. Politics in the Bible also models "social contract theory" which says a person's moral obligations to form the society in which they live are dependent on that agreement. This implies a moral respect for God and his laws which is not a result of law, but pre-exists law. Walzer asserts this is what makes it possible for someone like Amos, "an herdsman and gatherer of sycamore fruit," to confront Priests and Kings, and remind them of their obligations. Moral law is, therefore, politically democratized in the Bible.

He goes on to explain that "Israel's almost-democracy has three features having to do with covenant, law, and prophecy." First, God's covenant requires everyone adhere equally to the agreement they made, as in later "general will" theories of democracy. "In the biblical texts, poor people, women, and even strangers, are recognized as moral agents in their own right whatever the extent of that agency might be." Second, everyone was subject to God's law. Kings were not involved in making or interpreting the law, but were as subject to it, in principle, as every other Israelite. Third, the prophets spoke as the interpreters of divine law in public places to ordinary people. They came from every social strata and denounced the most powerful men in society—and everyone else too. "Their public and uninhibited criticism is an important signifier of religious democracy."

Christianity has taken its political ethics from both Israel and Jesus. Political science scholar Amy E. Black says Jesus' command to pay taxes (Matthew 22:21), was not simply an endorsement of government, but was also a refusal to participate in the fierce political debate of his day over the Poll tax. Black quotes Old Testament scholar Gordon Wenham as saying, Jesus' response "implied loyalty to a pagan government was not incompatible with loyalty to God." However, debate on this issue continues. Anabaptists advocate for the most limited involvement in politics possible; Lutherans support government but also recognize its spiritual and moral limitations; the distinctly American Black church is well aware of the possible short-comings and benefits of government, and tends to view politics as a group endeavor, not an individual one; Reformed tradition emphasizes God's sovereignty, that government is instituted by God, and supports advocating for policies in the public realm; and Catholic political thought says all human life is political in nature. It is therefore the responsibility of the state to cultivate the common good, and the responsibility of believers to participate in the effort to make sure it does.

War and peace

Warfare as a political act of nationhood, is a topic the Bible addresses ethically, both directly and indirectly, in four ways: there are verses that support pacifism, and verses that support non-resistance; 4th century theologian Augustine identified aspects of just war in the Bible, and preventive war which is sometimes called crusade has also been supported using Bible texts. Near Eastern scholar Susan Niditch says "...To understand attitudes toward war in the Bible is thus to gain a handle on war in general..."

Pacifism is not in the Hebrew Bible, but an ethic of peace can be found there. The term peace is mentioned 429 times in the Bible—and more than 2500 times in classical Jewish sources. Many of those refer to peace as a central part of God's purpose for mankind. Political activist David Cortright writes that shalom (peace in Hebrew) is a complex word with levels of meaning that embody the conditions and values necessary to prevent war: "social justice, self-determination, economic well-being, human rights, and the use of non-violent means to resolve conflict." Most texts used to support pacifism are in the New Testament, such as Matthew 5:38-48 and Luke 6:27-36, but not all. Passages of peace from the Hebrew Bible, such as Micah 4:3: "They will beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks," are also often cited. According to theologian Myron S. Augsberger, pacifism opposes war for any reason. The ethic is founded in separation from the world and the world's ways of doing things, obeying God first rather than the state, and belief that God's kingdom is beyond this world. Bible scholar Herman A. Hoyt says Christians are obligated to follow Christ's example, which was an example of non-resistance. This obligation is to individual believers, not corporate bodies, or "unregenerate worldly governments."

Near Eastern scholar Yigal Levin, along with archaeologist Amnon Shapira, write that the ethic of war in the Bible is based on the concept of self-defense. Self-defense, or defense of others, is necessary for a war to be understood as a just war. Levin and Shapira say forbidding war for the purpose of expansion (Deuteronomy 2:2-6,9,17-19), the call to talk peace before war (Deuteronomy 20:10), the expectation of moral disobedience to a corrupt leader (Genesis 18:23-33;Exodus 1:17, 2:11-14, 32:32;1 Samuel 22:17), as well as a series of verses governing treatment of prisoners (Deuteronomy 21:10-14; 2 Chronicles 28:10-15; Joshua 8:29,10:26-27), respect for the land (Deuteronomy 20:19), and general "purity in the camp" (Deuteronomy 20:10-15) are aspects of the principles of just war in the Bible.

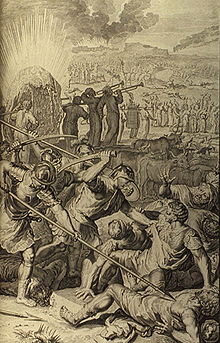

In Exodus, Deuteronomy, Joshua, and both books of Kings, warfare includes a variety of conflicts with Amalekites, Canaanites, and Moabites. For the modern reader, after centuries of imperialism, the ethics of conquest is problematic. God commands the Israelites to conquer the Promised Land, placing city after city "under the ban," the herem of total war. This meant every man, woman and child was to be killed. This leads many contemporary scholars to characterize herem as a command to commit genocide. Michael Walzer writes that herem was the common approach to war among the nations surrounding Israel of the bronze age, and Hebrew scholar Baruch A. Levine indicates Israel imported the concept from them. Walzer points out that verses 15 to 18 of Deuteronomy 20 are very old, suggesting "the addition of herem to an older siege law." He goes on to say the earliest biblical sources show there are two ethics of conquest in the Bible with laws supporting each. Beginning at Deuteronomy 20:10-14 there is a limited war/(just war) doctrine consistent with Amos and First and Second Kings. From Deuteronomy 20 on, both war doctrines are joined without one superseding the other. However, starting in Joshua 9, after the conquest of Ai, Israel's battles are described as self-defense, and the priestly authors of Leviticus, and the Deuteronomists, are careful to give God moral reasons for his commandment.

Criminal justice

Main article: Criminal justice See also: Eye for an eyeLegal scholar Jonathan Burnside says biblical law is not fully codified, but it is possible to discern its key ethical elements. Key elements in biblical criminal justice begin with the belief in God as the source of justice and the judge of all. Criminal justice scholar Sam S. Souryal says the Bible emphasizes that ethical knowledge and moral character are central to the administration of justice. Souryal says foremost among the biblical ethical principles that ensure criminal justice are those prohibiting "lying and deception, racial prejudice and racial discrimination, egoism and the abuse of authority." In the Bible, human judges are thought capable of mediating even divine decisions if they have sufficient moral capacity and wisdom. Biblical criminal justice supports the fight to overthrow oppressors and liberate the oppressed, to put things right from God's perspective, and to put justice in the hands of the many and not just the few. It respects local courts, and involves a range of authorities in an effort to apply practical wisdom and a "divine" sense of justice.

Ethicist Christopher Marshall writes that covenant law included features that have become standard in human rights law: due process, fairness in criminal procedures, and equity in the application of law. Judges are not to accept bribes (Deuteronomy 16:19), were required to be impartial to native and stranger alike (Leviticus 24:22; Deuteronomy 27:19), to the needy and the powerful alike (Leviticus 19:15), and to rich and poor alike (Deuteronomy 1:16,17; Exodus 23:2-6). The right to a fair trial, and fair punishment, are also required (Deuteronomy 19:15; Exodus 21:23-25). Those most vulnerable in a patriarchal society—children, women and strangers—were singled out for special protection (Psalm 72:2,4).

Human relationships

Main article: The Bible and slavery

Caring for others is a foundational principle of biblical ethics. Leviticus 19:18 includes "love your neighbor as yourself" as does Mark 12:31; Matthew has it in three places, and James has it in the second chapter, verse 8. Catholic Social Teaching lays out seven biblical ethical principles for human interaction: (1) the worth and dignity of human life (Genesis 1:26-27); (2) the call to family, community, and participation (Genesis 1:22,1 Corinthians 12:25, Galatians 5:14-16); (3) that we are endowed with natural, inalienable rights and responsibilities (Galatians 6:4,5); (4) especially to the poor and the vulnerable (Matthew 5, James 1:26,27); (5) that there is dignity in work (Colossians 3:23); (6) that we need unity and solidarity to accomplish God's will (1 Peter 3:8,9); (7) and care for God's creation (Genesis 1:26). Theologian P. J. Harland explains that, the belief man is in some way like God, confers a reflected worth and dignity to each human being.

Women, marriage and family

Main articles: Sexual slavery, Women in the Bible, Pilegesh, Polygyny, and Jesus' interactions with women

Textual scholar Phyllis Trible says "considerable evidence depicts the Bible as a document of male supremacy." However, Hebrew Bible scholar Tikva Frymer-Kensky says there are also evidences of "gender blindness" and equality in the Bible. Most theologians agree the Hebrew Bible does not depict women as different in essence from males in the manner the Greeks and Romans did. However, most scholars also agree the Bible is a patriarchal document from a patriarchal age.

Bible scholar Katrine Evans says Jesus repeatedly challenged the various discriminations of ancient Israel that rendered some, such as women, as outsiders. The New Testament refers to a number of women in Jesus’ inner circle. New Testament scholar Ben Witherington III says "Jesus broke with both biblical and rabbinic traditions that restricted women's roles in religious practices, and He rejected attempts to devalue the worth of a woman, or her word of witness."

Political science scholar Amy E. Black writes that "God created humanity to live and thrive in community, beginning with the foundational relationships of marriage and family, and extending outward to other forms of community." Bible scholar Gordon Hugenberger writes that marriage in the Bible has a legal, cultural, ethical and covenantal basis, and that scholarship in this area has produced dissimilar and contradictory results.

Sexual ethics

See also: Religion and sexuality, Sexual ethics, Christianity and homosexuality, and Judaism and sexualityThe concepts of purity, pollution and sexuality are inextricably linked in the Bible. Near Eastern scholar Eve Levavi Feinstein writes that purity and pollution are not primitive, exotic ideas, but are instead inherent in the way all human individuals and societies think and interact with their world. Concepts of what degrades or defiles us do change, but the belief there are things that can degrade and defile, does not. The Bible has two categories of pollution: ritual pollution and moral pollution. Pollution concerns arise when things and people are outside the established order.

Feinstein says the Hebrew Bible never uses the term 'pure' (טָהֵר) to describe virginity, but does use it to describe a married woman who has not committed adultery (Numbers 5:28). The blood of slain innocents is said to pollute the land in Numbers 35:34. According to Leviticus 11, eating prohibited meats pollutes the consumer's throat. Wanton, unrepentant sins are seen as having a contaminating effect on the sanctuary similar to environmental pollution. Sexual pollution is attributed to people and sometimes, indirectly, to the land but it is not said that it pollutes the sanctuary and is not necessarily a result of sin, since ritual pollution can result from prescribed sex as well as proscribed sex.

Early Church Fathers of Christianity advocated against adultery, polygamy, homosexuality, pederasty, bestiality, prostitution, and incest while advocating for the sanctity of the marriage bed. The central Christian prohibition against such porneia, which is a single name for that array of sexual behaviors, "collided with deeply entrenched patterns of Roman permissiveness where the legitimacy of sexual contact was determined primarily by social status." St. Paul, whose views became dominant in early Christianity, made the body into a consecrated space, a point of mediation between the individual and the divine, which separated the Christian concept of sexuality from its societal dimension entirely. Same-sex attraction spelled the estrangement of men and women at the very deepest level of their inmost desires. Paul's over-riding sense that gender—rather than status or power or wealth or position—was the prime determinant in the propriety of the sex act was momentous. Over the first three centuries of the early Church, Christianity's ethic on sexuality was elaborated, an entire debate about free will was generated within the communities and in debate with people outside of those communities, and by around 300 BCE, the orthodox position had generally crystalized into seeing celibacy as best-—the Symposium of Methodius is an example of a Christian "philosophy distinctly apart from the machinery of society."

Economics

The Bible gives images of social justice, economics and labor, and business ethics.

Environmental

See also: Animal ethicsThe Bible has a great deal to say on bioethics and animals.

Criticism

See also: Criticism of the BibleBertrand Russell stated that,

It seems to me that the people who have held to it have been for the most part extremely wicked....I say quite deliberately that the Christian religion, as organized in its churches, has been and still is the principal enemy of moral progress in the world."

Elizabeth Anderson, a Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, states that "the Bible contains both good and evil teachings", and it is "morally inconsistent".

Anderson criticizes commands God gave to men in the Old Testament, such as: kill adulterers, homosexuals, and "people who work on the Sabbath" (Leviticus 20:10; Leviticus 20:13; Exodus 35:2, respectively); to commit ethnic cleansing (Exodus 34:11-14, Leviticus 26:7-9); commit genocide (Numbers 21: 2-3, Numbers 21:33–35, Deuteronomy 2:26–35, and Joshua 1–12); and other mass killings. Anderson considers the Bible to permit slavery, the beating of slaves, the rape of female captives in wartime, polygamy (for men), the killing of prisoners, and child sacrifice. She also provides a number of examples to illustrate what she considers "God's moral character": "Routinely punishes people for the sins of others ... punishes all mothers by condemning them to painful childbirth", punishes four generations of descendants of those who worship other gods, kills 24,000 Israelites because some of them sinned (Numbers 25:1–9), kills 70,000 Israelites for the sin of David in 2 Samuel 24:10–15, and "sends two bears out of the woods to tear forty-two children to pieces" because they called someone names in 2 Kings 2:23–24.

Anderson criticizes what she terms morally repugnant lessons of the New Testament. She claims that "Jesus tells us his mission is to make family members hate one another, so that they shall love him more than their kin" (Matt 10:35-37), that "Disciples must hate their parents, siblings, wives, and children (Luke 14:26)", and that Peter and Paul elevate men over their wives "who must obey their husbands as gods" (1 Corinthians 11:3, 14:34-5, Eph. 5:22-24, Col. 3:18, 1 Tim. 2: 11-2, 1 Pet. 3:1). Anderson states that the Gospel of John implies that "infants and anyone who never had the opportunity to hear about Christ are damned , through no fault of their own".

Simon Blackburn states that the "Bible can be read as giving us a carte blanche for harsh attitudes to children, the mentally handicapped, animals, the environment, the divorced, unbelievers, people with various sexual habits, and elderly women".

Blackburn criticizes what he terms morally suspect themes of the New Testament. He notes some "moral quirks" of Jesus: that he could be "sectarian" (Matt 10:5–6), racist (Matt 15:26 and Mark 7:27), and placed no value on animal life (Luke 8: 27–33).

Blackburn provides examples of Old Testament moral criticisms such as the phrase in Exodus 22:18 that has "helped to burn alive tens or hundreds of thousands of women in Europe and America": "Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live," and notes that the Old Testament God apparently has "no problems with a slave-owning society", considers birth control a crime punishable by death, and "is keen on child abuse". Additional examples that are questioned today are: the prohibition on touching women during their "period of menstrual uncleanliness (Lev. 15:19–24)", the apparent approval of selling daughters into slavery (Exodus 21:7), and the obligation to put to death someone working on the Sabbath (Exodus 35:2).

Several Biblical prescriptions may not correspond to modern notions of justice in relation to concepts such as slavery (Lev. 25:44-46), intolerance of religious pluralism (Deut. 5:7, Deut. 7:2-5) or of freedom of religion (Deut. 13:6-12), discrimination and racism (Lev. 21:17-23, Deut. 23:1-3), treatment of women, honor killing (Ex. 21:17, Leviticus 20:9, Ex. 32:27-29), genocide (Num. 31:15-18, 1 Sam. 15:3), religious wars, and capital punishment for sexual behavior like adultery and sodomy and for Sabbath breaking (Num. 15:32-36).

The Book of Proverbs recommends corporal punishment when disciplining a child:

Foolishness is bound in the heart of a child; but the rod of correction shall drive it far from him.

— Proverbs 22:15

Supersessionism

Main articles: Antinomianism, Biblical law in Christianity, and Moral relativismThe predominant Christian view is that Jesus mediates a New Covenant relationship between God and his followers and abolished some Mosaic Laws, according to the New Testament (Hebrews 10:15–18; Gal 3:23–25; 2 Cor 3:7–17; Eph 2:15; Heb 8:13, Rom 7:6 etc.). From a Jewish perspective however, the Torah was given to the Jewish people as an eternal covenant (Exod 31:16–17, Exod 12:14–17, Mal 3:6–7) and will never be replaced or added to (Deut 4:2, 13:1). There are differences of opinion as to how the new covenant affects the validity of biblical law. The differences are mainly as a result of attempts to harmonize biblical statements to the effect that the biblical law is eternal (Exodus 31:16–17, 12:14–17) with New Testament statements that suggest that it does not now apply at all, or at least does not fully apply. Most biblical scholars admit the issue of the Law can be confusing and the topic of Paul and the Law is still frequently debated among New Testament scholars (for example, see New Perspective on Paul, Pauline Christianity); hence the various views.

War and genocide

Criminal justice and human rights

Patriarchy

Sexual intolerance

Problem of evil

Further information: TheodicyA central issue in monotheist ethics is the problem of evil, the apparent contradiction between a benevolent, all-powerful God and the existence of evil and hell (see Problem of Hell). Theodicy seeks to explain why one may simultaneously affirm God's goodness, and the presence of evil in the world. Descartes in his Meditations considers, but rejects, the possibility that God is an evil demon ("dystheism").

The Bible contains numerous examples seemingly unethical acts of God.

- In the Book of Exodus, God deliberately "hardened Pharaoh's heart", making him even more unwilling to free the Hebrew slaves (Exod 4:21, Rom 9:17–21).

- Genocidal commands of God in Deuteronomy, such as the call to eradicate all the Canaanite tribes including children and infants (Deut 20:16–17). According to the Bible, this was to fulfill God's covenant to Israel, the "promised land" to his chosen people.(Deuteronomy 7:1–25)

- God ordering the Israelites to undertake punitive military raids against other tribes. This happened, for instance, to the Midianites of Moab, who had enticed some Israelites into worshipping local gods (Numbers 25:1–18). The entire tribe was exterminated, except for the young virgin girls, who were kept by the Israelites as slaves (Numbers 31:1–54). In 1 Samuel 15:3, God orders the Israelites to "attack the Amalekites and totally destroy everything that belongs to them. Do not spare them; put to death men and women, children and infants, cattle and sheep, camels and donkeys."

- In the Book of Job, God allows Satan to plague his loyal servant Job with devastating tragedies leaving all his children dead and himself poor. The nature of divine justice becomes the theme of the entire book. However, after he got through his troubles his health was restored and all he had was doubled.

- Sending evil spirits to people (1 Samuel 18:10, Judges 9:23).

- Punishing the innocent for the sins of other people (Isa 14:21, Deut 23:2, Hosea 13:16).

- In the Book of Isaiah, God created all natural disasters/the evil in the world. (Isaiah 45–7)

See also

- Antisemitism and the New Testament

- Brotherly love (philosophy)

- But to bring a sword

- The Bible and slavery

- Death penalty in the Bible

- Evolutionary ethics

- Outline of ethics

- Secular ethics

References

- ^ Jones, David W. (2013). Heimbach, Daniel R. (ed.). An Introduction to Biblical Ethics. Nashville, Tennessee: B&H Academic Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4336-6969-9.

- ^ Mittleman, Alan L. (2012). A Short History of Jewish Ethics: Conduct and Character in the Context of Covenant. Chichester, West Suffix: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8942-2.

- Schulweis, Harold M. (2010). Evil and the Morality of God. Brooklyn, New York: KTAV Publishing House. ISBN 978-1-60280-155-4.

- Murray, John (1957). Principles of Conduct: Aspects of Biblical Ethics. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans Pub. Co. ISBN 0-8028-1144-2.

- Mott, Steven (2011). Biblical Ethics and Social Change (Second ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973937-0.

- ^ Gill, Robin (2012). "Preface". In Gill, Robin (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Christian Ethics (Second ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00007-0.

- ^ Lundberg, Matthew D. (2011). "Creation ethics". In Green, Joel B.; Lapsley, Jaqueline E.; Miles, Rebekah; Verhey, Allen (eds.). Dictionary of Scripture and Ethics. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0-8010-3406-0.

- Gunkel, Hermann; Zimmern, Heinrich (2006). Creation And Chaos in the Primeval Era And the Eschaton: A Religio-historical Study of Genesis 1 and Revelation 12. Translated by Whitney Jr., K. William. Grand Rapids: Eerdman's.

- Mathews, "Kenneth A." (1996). The New American Commentary: Genesis 1-11:26. Vol. 1A. Nashville, Tennessee: Broadman and Holman Publishers. pp. 92–95. ISBN 978-0-8054-0101-1.

- Brueggemann, Walter (2010). Genesis: Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster Jon Know Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-664-23437-9.

- Creach, Jerome F.D. (2013). Violence in Scripture: Interpretation: Resources for the Use of Scripture in the Church. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-23978-7.

- ^ Atkinson, David J.; Field, David F.; Holmes, Arthur F.; O'Donovan, Oliver, eds. (1995). "Violence". New Dictionary of Christian Ethics & Pastoral Theology. Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic. ISBN 978-0-8308-1408-4.

- Kleven, Terence J. (2007). "Old Testament teaching on necessity in creation and its implication for the doctrine of atonement". In Treschow, Michael; Otten, Wiilemien; Hannam, Walter (eds.). Divine Creation in Ancient, Medieval, and Early Modern Thought. Boston, Massachusettes: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15619-7.

- Bromily, Geoffrey W. (1988). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8028-3784-0. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Willis, Roy (2012). World Mythology. New York: Metro Books. ISBN 978-1-4351-4173-5.

- ^ Marshall, Christopher (1999). ""A Little lower that the Angels" Human rights in the biblical tradition". In Atkin, Bill; Evans, Katrine (eds.). Human Rights and the Common Good: Christian Perspectives. Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University Press. ISBN 0 86473 362 3.

- ^ Hoekema, Anthony A. (1985). Created in God's Image. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans. ISBN 0-85364-626-0. Cite error: The named reference "Anthony A. Hoekema" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Gushee, David P. (2014). In the Fray: Contesting Christian Public Ethics, 1994–2013. Eugene, Oregon,: Cascade Books. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-62564-044-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Nico Vorster, Nico Vorster (2011). Created in the Image of God: Understanding God's Relationship with Humanity. Eugene, Oregon: Pickwick Publications. ISBN 978-1-61097-223-9.

- ^ Ritenour, Shawn (2010). Foundations of Economics: A Christian View. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock. ISBN 978-1-55635-724-4.

- ^ John Rogerson, "The Old Testament and Christian Ethics," p. 36, in Robin Gill (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Christian Ethics, 2d Edition (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2012). Rogerson points to N.H.G. Robinson, The Groundwork of Christian Ethics (London: Collins, 1971), 31–32.

- ^ Meyers, Carol (1988). Discovering Eve: Ancient Israelite Women in Context. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195049343. OCLC 242712170.

- ^ Frymer-Kensky, Tikva (2006). Studies in Bible and feminist criticism (1st ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 9780827607989.

- Lindsey, Linda L (2016). Gender Roles: A Sociological perspective. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-205-89968-5.

- ^ Trible, Phyllis (1984). Texts of Terror: Literary feminist readings of biblical narratives. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-80061-537-6.

- Blomberg, =Craig L. (2009). "Women in Ministry: a complementarian perspective". In Beck, James R. (ed.). Two views on women in ministry. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan. ISBN 9780310254379.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Keenan, James (2011). "Conscience". In Lapsley, Jaqueline E.; Miles, Rebekah; Verhey, Allen; Green, Joel B. (eds.). Dictionary of Scripture and Ethics. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0-8010-3406-0.

- Greenberg, Irving (2000). "Judaism and Christianity: Covenants of Redemption". In Frymer-Kensky, Tikva; Signer, Michael A.; Novak, David; Ochs, Peter; Sandmel, David Fox (eds.). Christianity in Jewish terms. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-81333-780-7.

- ^ Harrington, Daniel J.; Keenan, James F. (2002). Jesus and Virtue Ethics: Building Bridges Between New Testament Studies and Moral Theology. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1-58051-125-2.

- ^ Unterman, Jeremiah (2017). Justice for All: How the Jewish Bible Revolutionized Ethics. Philadephia, Pennsylvania: The Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 978-0-82761-270-9.

- The Sermon on the mount: a theological investigation by Carl G. Vaught 2001 ISBN 978-0-918954-76-3 pages xi–xiv

- ^ Walzer, Michael (2012). In God's Shadow: Politics in the Hebrew Bible. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18044-2.

- Deut 4:6–8

- ^ Black, Amy E. (2015). "Christian Traditions and Political Engagement". In Black, Amy E.; Gundry, Stanley N. (eds.). Five Views on the Church and Politics. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-51793-1.

- Clouse, Robert G., ed. (1986). War: Four Christian Views. Winona Lake, Indiana: BMH Books. ISBN 978-0-88469-097-9.

- Niditch, Susan (1993). War in the Hebrew Bible: A study in the Ethics of Violence. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507638-9.

- Sprinkle, Preston (2013). Fight: A Christian Case for Non-Violence. Colorado Springs, Colorado: David C. Cook. ISBN 978-1-4347-0492-4.

- Cortright, David (2008). Peace: A History of Movements and Ideas. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85402-3.

- ^ Augsberger, Myron S. (1986). "Christian pacifism". In Clouse, Robert G. (ed.). War: Four Christian views. Winona Lake, Indianna: BMH Books. ISBN 978-0-88469-097-9.

- Siebert, Eric (2012). The Violence of Scripture: Overcoming the Old Testament's Troubling Legacy. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-2432-4.

- ^ Hoyt, Herman A. (1986). "Non-resistance". In Clouse, Robert G. (ed.). War: Four Christian Views. Winona Lake, Indianna: BMH books. ISBN 0-88469-097-0.

- Holmes, Arthur F. (1986). "The Just War". In Clouse, Robert G. (ed.). War: Four Christian Views. Winona Lake, Indianna: BMH Books. ISBN 978-0-88469-097-9.

- ^ Levin, Yigal; Shapira, Amnon (2012). "Epilogue: War and peace in Jewish tradition-seven anomalies". In Levin, Yigal; Shapira, Amnon (eds.). War and Peace in Jewish Tradition: From the Biblical World to the Present. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-58715-0.

- Hunter, A. G. (2003). Bekkencamp, Jonneke; Sherwood, Yvonne (eds.). Denominating Amalek: Racist stereotyping in the Bible and the Justification of Discrimination", in Sanctified aggression: legacies of biblical and post biblical vocabularies of violence. Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Ruttenberg, Danya (Feb 1987). Jewish Choices, Jewish Voices: War and National Security.

- Fretheim, Terence (2004). "'I was only a little angry': Divine Violence in the Prophets". Interpretation. 58.4.

- Stone, Lawson (1991). "Ethical and Apologetic Tendencies in the Redaction of the Book of Joshua". Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 53.1.

- Deut 20:16–18

- Ian Guthridge (1999). The Rise and Decline of the Christian Empire. Medici School Publications, Australia. ISBN 978-0-9588645-4-1.

- Ruttenberg, Danya, Jewish Choices, Jewish Voices: War and National Security Danya Ruttenberg (Ed.) page 54 (citing Reuven Kimelman, "The Ethics of National Power: Government and War from the Sources of Judaism", in Perspectives, Feb 1987)

- Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A.Dirk, eds. (2010). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923211-6.

- Grenke, Arthur (2005). God, greed, and genocide: the Holocaust through the centuries. New Academia Publishing.

- Chazan, Robert; Hallo, William W.; Schiffman, Lawrence H., eds. (1999). כי ברוך הוא: Ancient Near Eastern, Biblical, and Judaic Studies in Honor of Baruch A. Levine. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. pp. 396–397. ISBN 1-57506-030-2.

- Crook, Zeba A. (2006). "Covenantal Exchange as a Test Case". In Esler, Philip Francis (ed.). Ancient Israel: The Old Testament in Its Social Context. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press. ISBN 0-8006-3767-4.

- Deut 20:10–14

- Deut 9:5

- Creach, Jerome (Jul 2016). "Violence in the Old Testament". The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.001.0001/acrefore-9780199340378-e-154 (inactive 2018-04-11). Retrieved 23 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2018 (link) - ^ Burnside, Jonathan (2011). God, Justice, and Society: Aspects of Law and Legality in the Bible. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19975-921-7.

- Swartley, Willard (2014). "God's moral character as the basis of human ethics: Foundational convictions". In Brenneman, Laura; Schantz, Brad D. (eds.). Struggles for Shalom: Peace and Violence across the Testaments. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-62032-622-0.

- Souryal, Sam S. (2015). Ethics in Criminal Justice: In Search of the Truth (6th ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-323-28091-4.

- Berman, Joshua A. (2008). Created Equal: How the Bible Broke with Ancient Political Thought. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537470-4.

- Harland, P. J. (1996). The Value of Human Life: A Study of the Story of the Flood (Genesis 6-9). New York: E. J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-10534-4.

- Trible, Phyllis (1973). "Depatriarchalizing in Biblical Interpretation". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 41 (1): 30–48. JSTOR 1461386.

- Witherington III, Ben (1984). Women in the Ministry of Jesus: A Study of Jesus' attitudes to women and their roles as reflected in his earthly life. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 34781 5.

- Hugenberger, Gordon Paul (2014). Marriage as a Covenant: Biblical Law and Ethics as Developed from Malachi (Reprint ed.). Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock. ISBN 1-62032-456-3.

- ^ Feinstein, Eve Levavi (2014). Sexual Pollution in the Hebrew Bible. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-939554-5.

- Witte (1997), p. 20.

- ^ Harper, Kyle (2013). From Shame to Sin: The Christian Transformation of Sexual Morality in Late Antiquity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-674-07277-0.

- Russell, Bertrand (1957). Why I Am Not a Christian: And Other Essays on Religion and Related Subjects. New York: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-671-20323-8.

- Elizabeth Anderson, "If God is Dead, Is Everything Permitted?" In Hitchens, Christopher (2007). The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-306-81608-6.

- ^ Elizabeth Anderson, "If God is Dead, Is Everything Permitted?" In Hitchens, Christopher (2007). The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press. p. 337. ISBN 978-0-306-81608-6.

- Elizabeth Anderson, "If God is Dead, Is Everything Permitted?" In Hitchens, Christopher (2007). The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press. pp. 336–337. ISBN 978-0-306-81608-6.

- Elizabeth Anderson, "If God is Dead, Is Everything Permitted?" In Hitchens, Christopher (2007). The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-306-81608-6.

- Elizabeth Anderson, "If God is Dead, Is Everything Permitted?" In Hitchens, Christopher (2007). The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press. p. 339. ISBN 978-0-306-81608-6.

- Blackburn, Simon (2001). Ethics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-19-280442-6.

- Blackburn, Simon (2001). Ethics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-19-280442-6.

-

Blackburn, Simon (2003). Ethics: A Very Short Introduction. Very Short Introductions. OUP. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9780191577925. Retrieved 2015-09-11.

Then the persona of Jesus in the Gospels has his fair share of moral quirks. He can be sectarian: 'Go not into the way of the Gentiles, and into any city of the Samaritans enter ye not. But go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel' (Matt. 10:5-6).

- Blackburn, Simon (2001). Ethics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 10, 12. ISBN 978-0-19-280442-6.

- Blackburn, Simon (2001). Ethics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-19-280442-6.

- Gundry, ed., Five Views on Law and Gospel. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1993).

- The Dominion of Love: Animal Rights According to the Bible, Norm Phelps, p. 14