This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 121.58.195.242 (talk) at 01:13, 14 March 2019. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:13, 14 March 2019 by 121.58.195.242 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Salvation history (Template:Lang-de) seeks to understand the personal redemptive activity of God within human history to affect his eternal saving intentions.

This approach to history is found in parts of the Old Testament written around the sixth century BC, such as Deutero-Isaiah and some of the Psalms. In Deutero-Isaiah, for example, Yahweh is portrayed as causing the fall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire at the hands of Cyrus the Great and the Persians, with the aim of restoring his exiled people to their land.

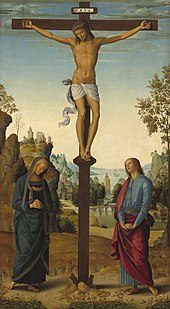

The salvation history approach was adopted and deployed by Christians, beginning with Paul in his epistles. He taught a dialectical theology wherein believers were caught between the "already" of Christ's death and resurrection, and the "not yet" of the coming Parousia (or Christ's return to Earth at the end of human history). He sought to explain the Christ's mystery through the lens of the history of the Hebrew scriptures, for example, by drawing parallels and contrasts between Adam's disobedience and Christ's faithfulness on the cross.

In the context of Christian theology, this approach reads the books of the Bible as a continuous history. It understands events such as the fall at the beginning of history (Book of Genesis), the covenants established between God and Noah, Abraham, and Moses, the establishment of David's dynasty in the holy city of Jerusalem, etc., as seminal moments in the history of humankind and its relationship to God, namely, as necessary events preparing for the salvation of all by Christ's crucifixion and resurrection.

See also

References

- "Paul and Salvation History", in Justification and Variegated Nomism; Volume 2 – The Paradoxes of Paul, eds. D. A. Carson, Mark A. Seifrid, and Peter T. O'Brien (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker, 2004), p. 297.

- Exile and Restoration: A Study of Hebrew Thought of the Sixth Century BC, Peter R. Ackroyd (London: SCM Press, 1968), pp. 130–133.

Yo mama still so fat she s t i l l cant eat your toes