This is an old revision of this page, as edited by IainDavidson (talk | contribs) at 22:52, 27 November 2006 (Added link to 2006 tropical storm Durian.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:52, 27 November 2006 by IainDavidson (talk | contribs) (Added link to 2006 tropical storm Durian.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| Durian | |

|---|---|

| |

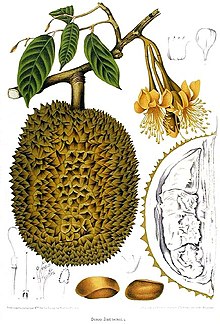

| Fruit of Durio zibethinus. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida |

| Order: | Malvales |

| Family: | Malvaceae (Bombacaceae) |

| Genus: | Durio L. |

| Species | |

|

There are currently 30 recognised species (see text) | |

The durian (IPA: ) is the fruit of trees of the genus Durio. There are 30 recognised Durio species, all native to southeastern Asia and at least nine of which produce edible fruit. Durio zibethinus is the only species available in the international market; other species are sold in their local region. The durian fruit is distinctive for its large size, unique odour, and a formidable thorn-covered husk. Its name comes from the Malay word duri, meaning "thorn".

The fruit can grow up to 40 cm long and 30 cm in diameter, and typically weighs one to five kilograms. Its shape ranges from oblong to round, the colour of its husk green to brown and its flesh pale-yellow to red, depending on species. The hard outer husk is covered with sharp, prickly thorns, while the edible custard-like flesh within emits a strong, distinctive odour. Some regard this odour as fragrant while others find it overpowering or offensive. The seed can also be eaten after boiling, drying, frying or roasting.

Species

- For the complete list of known species of Durio, see List of Durio species.

Durian trees are relatively large, growing up to 25–50 metres in height, depending on species. The leaves are evergreen, opposite, elliptic to oblong and 10–18 cm long. The flowers are produced in three to thirty clusters together on large branches and the trunk, each flower having a calyx (sepals) and 5 (rarely 4 or 6) petals. Durian trees have one or two flowering and fruiting periods each year, although the timing of these varies depending on species, cultivars and localities. A typical durian tree can bear fruit after four or five years. The durian fruit, which can hang from any branch, matures in about three months after pollination. Among the thirty known species of Durio, so far nine species have been identified to produce edible fruits. They are Durio zibethinus, Durio dulcis, Durio grandiflorus, Durio graveolens, Durio kutejensis, Durio lowianus, Durio macrantha, Durio oxleyanus and Durio testudinarum. However, there are many species for which the fruit has never been collected or properly examined, and other species with edible fruit may exist.

D. zibethinus is the only species commercially cultivated on a large scale and available outside of its native region. Since this species is open-pollinated, it shows considerable diversity in fruit colour and odour, size of flesh and seed, and tree phenology. In the species name, zibethinus refers to the Indian civet, Viverra zibetha. There is disagreement regarding whether this name, bestowed by Linnaeus, refers to civets eating durian fruit — which they have been known to do — or to the durian smelling like the civet.

Durian flowers are large and feathery with copious nectar, and give off a heavy, sour and buttery odour. These features are typical of flowers which are pollinated by certain species of bats while they eat nectar and pollen. According to a research conducted in Malaysia during 1970s, durians were pollinated almost exclusively by cave fruit bats (Eonycteris spelaea). However, a more recent research done in 1996 indicated that two species, D. grandiflorus and D. oblongus, were pollinated by spiderhunters (Nectariniidae) and that the other species, D. kutejensis, was pollinated by giant honey bees and birds as well as bats.

Cultivars

Numerous cultivars of durian have arisen in southeastern Asia over the centuries. They used to be grown from seeds with superior quality, but are now propagated by layering, marcotting, or more commonly, by grafting, including bud, veneer, wedge, whip or U-grafting onto seedlings of random rootstocks.

More than 200 cultivars of D. zibethinus exist in Thailand, Chanee being the most preferred rootstock due to its resistance to infection by Phytophthora palmivora. There are more than 100 registered cultivars in Malaysia and many superior cultivars have been identified through competitions held at the annual Malaysian Agriculture, Horticulture and Agrotourism Show. In Vietnam, the same process has been done through competitions held by the Southern Fruit Research Institute.

Most cultivars have both a common name and also a code number starting with "D". For example, some popular clones are Kop (D99), Chanee (D123), Tuan Mek Hijau (D145), Kan Yao (D158), Mon Thong (D159), Kradum Thong, and with no common name, D24. Each cultivar has a distinct taste and odour. Among all the cultivars in Thailand, though, only four see large scale commercial cultivation: Chanee, Kradum Thong, Mon Thong, and Kan Yao. Durian consumers do express preferences for specific cultivars, which fetch higher prices in the market.

Availability

The durian is native to Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei. It is grown in areas with a similar climate. The centre of ecological diversity for durians is the island of Borneo, where it is prized by the local people, a passion shared by the orangutan population. Along with D. zibethinus, other edible species of Durio such as D. dulcis, D. graveolens, D. kutejensis, D. oxleyanus and D. testudinarium are sold in local markets in Borneo.

D. zibethinus is not grown in Brunei, where consumers prefer other species such as D. graveolens, D. kutejensis and D. oxyleyanus. These species are commonly distributed in Brunei and together with other species like D. testudinarium and D. dulcis, represent rich genetic diversity.

Although the durian is not native to Thailand, it is currently one of the major exporters of durians. Other places where durians are grown include Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Myanmar, India, Sri Lanka, West Indies, Florida, Hawaii, Papua New Guinea, Polynesian Islands, Madagascar, southern China (Hainan Island), northern Australia, and Mindanao in the Philippines. In Mindanao, the centre of durian production is the Davao Region. The Kadayawan festival is an annual celebration featuring the durian in Davao City. There is some debate as to whether the durian is native to the Philippines, or has been introduced. Durian was introduced into Australia in the early 1960s and clonal material was first introduced in 1975. Over thirty clones of D. zibethinus and six Durio species have been subsequently introduced into Australia.

In season durians can be found in mainstream Japanese supermarkets. In the West, they are sold mainly by Asian markets.

Trade figures

Thailand grows and exports considerably more durian than any other nation, growing 781,000 of the world's total harvest of 1,400,000 tonnes of durian in 1999, and exporting 111,000 tonnes of that. Malaysia and Indonesia followed, both producing about 265,000 tonnes. Malaysia exported 35,000 tonnes in 1999. China is the major importer (65,000 tonnes in 1999), followed by Singapore (40,000 tonnes) and Taiwan (5000 tonnes). In 1999 the United States imported 2000 tonnes, mostly frozen, and the European Community imported 500 tonnes.

Flavour and odour

Writing in 1856, the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace provides a much-quoted description of the flavour of the durian:

"A rich custard highly flavoured with almonds gives the best general idea of it, but there are occasional wafts of flavour that call to mind cream-cheese, onion-sauce, sherry-wine, and other incongruous dishes. Then there is a rich glutinous smoothness in the pulp which nothing else possesses, but which adds to its delicacy."

Wallace cautions that "the smell of the ripe fruit is certainly at first disagreeable"; more recent descriptions by westerners can be more graphic. The English novelist Anthony Burgess famously said that dining on durian is like eating vanilla custard in a latrine. Travel and food writer Richard Sterling says:

"... its odor is best described as pig-shit, turpentine and onions, garnished with a gym sock. It can be smelled from yards away. Despite its great local popularity, the raw fruit is forbidden from some establishments such as hotels, subways and airports, including public transportation in Southeast Asia."

The unusual odour has prompted many people to search for an accurate description. Comparisons have been made with the civet, sewage, stale vomit, skunk spray, and used surgical swabs. The wide range of descriptions for the odour of durian may have a great deal to do with the wide variability of durian odour itself. Durians from different species or clones can have significantly different aromas, and the degree of ripeness has a great effect as well. In fact, three scientific analyses of the composition of durian aroma — from 1972, 1980, and 1995 — each found a different mix of volatile compounds, including many different organosulfur compounds, with no agreement on which may be primarily responsible for the distinctive odour.

This strong odour can be detected half a mile away by animals, thus luring them. In addition, the fruit is extremely appetising to a variety of animals, from squirrels to mouse deer, pigs, orangutan, elephants, and even carnivorous tigers. While some of these animals eat the fruit and dispose of the seed under the parent plant, others swallow the seed with the fruit and then transport it some distance before excreting it, the seed being dispersed as the result. The thorny armored covering of the fruit may have evolved because it discourages smaller animals, since larger animals are more likely to transport the seeds far from the parent tree.

History

The durian has been known and consumed in southeastern Asia since prehistoric times, but has only been known to the western world for about 600 years. The earliest known European reference on the durian is the record of Nicolo Conti who travelled to southeastern Asia in 15th century. Garcia de Orta described durians in Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas da India (1563). In 1741, Herbarium Amboinense by the German botanist Georgius Everhardus Rumphius (1627–1702) was published, providing the most detailed and accurate account of durians for over a century. The genus Durio has a complex taxonomy that has seen the subtraction and addition of many species since it was created by Rumphius. During the early stages of its taxonomical study, there was some confusion between durian and the soursop (Annona muricata), for both of these species had thorny green fruit. It is also interesting to note the Malay name for the soursop is durian Belanda, meaning "Dutch durian". In 18th century, Weinmann considered the durian to belong to Castaneae as its fruit was similar to the horse chestnut.

D. zibethinus was introduced into Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) by the Portuguese in the 16th century and was reintroduced many times later. It has been planted in the Americas but confined to botanical gardens. The first seedlings were sent from Kew Botanic Gardens of England, to St. Aromen of Dominica in 1884. The durian has been cultivated for centuries at the village level, probably since the late 18th century, and commercially in south-eastern Asia since the mid 20th century. In his book My Tropic Isle, E. J. Banfield tells how, in the early 20th century, a Singapore friend sent him a durian seed which he planted and cared for on his tropical island off the north coast of Queensland.

In 1949, the British botanist E. J. H. Corner published The Durian Theory or the Origin of the Modern Tree. His idea was that endozoochory (the enticement of animals to transport seeds in their stomach) arose before any other method of seed dispersal, and that primitive ancestors of Durio species were the earliest practitioners of that strategy, especially the red durian fruit exemplifying the primitive fruit of flowering plants.

Since the early 1990s, the domestic and international demand for durian in the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) region has increased dramatically, partly due to the increasing affluence in Asia.

Ripeness and selection

The ideal stage of ripeness to be enjoyed varies from region to region in south-east Asia. Generally, people in southern Thailand prefer their durians relatively young, before they have fallen from the tree. Eaten in this state, the clusters of fruit within the shell are still crisp in texture and mild in flavour. In northern Thailand, the preference is for the fruit to be as soft and pungent in aroma as possible. In Malaysia and Singapore, most consumers also prefer the fruit to fall from the tree and may even risk allowing the fruit to continue ripening before opening it. In this state, the flesh becomes richly creamy, the aroma pronounced and the flavour highly complex.

The differing preferences regarding ripeness among different consumers makes it hard to issue general statements about choosing a "good" durian. A durian that falls off the tree continues to ripen for two to four days, but after five or six days most would consider it overripe and unpalatable. The usual advice for a durian consumer choosing a whole fruit in the market is to examine the quality of the stem or stalk, which loses moisture as it ages: a big, solid stem is a sign of freshness. Reportedly, unscrupulous merchants wrap, paint, or remove the stalks altogether. Another frequent piece of advice is to shake the fruit and listen for the sound of the seeds moving within, indicating that the durian is very ripe, and the pulp has dried out somewhat.

Durians may be attacked by insect pests which lay eggs in the fruit. These develop into worm-like larvae, which burrow into the flesh of the fruit. Visible holes in the outside of the fruit can indicate the presence of larvae inside.

Uses

Culinary

Durian fruit is used to flavour a wide variety of sweet edibles such as traditional Malay candy, ice kachang, rose biscuits, cakes, and, with a touch of modern innovation, ice cream, milkshakes, mooncakes and even cappuccino. Pulut Durian is glutinous rice steamed with coconut milk and served with ripened durian. In Sabah, red durian (D. dulcis) is fried with onions and chilli and served as a side dish. Tempoyak refers to fermented durian, usually made from lower quality durian that is unsuitable for direct consumption. Tempoyak can be eaten either cooked or uncooked, is normally eaten with rice, and can also be used for making curry. Sambal Tempoyak is a Sumatran dish made from the fermented durian fruit, coconut milk, and a collection of spicy ingredients known as sambal.

In Thailand, blocks of durian paste are sold in the markets, though much of the paste is adulterated with pumpkin. Unripe durians may be cooked as vegetable, except in the Philippines, where all uses are sweet rather than savoury. Malaysians make both sugared and salted preserves from durian. When durian is minced with salt, onions and vinegar, it is called boder. The durian seeds, which are the size of chestnuts, can be eaten whether they are boiled, roasted or fried in coconut oil, with a texture that is similar to taro or yam, but stickier. In Java, the seeds are sliced thin and cooked with sugar as a confectionary. Uncooked durian seeds are toxic due to cyclopropene fatty acids and should not be ingested. Young leaves and shoots of the durian are occasionally cooked as greens. Sometimes the ash of the burned rind is added to special cakes. The petals of durian flowers are eaten in the Batak provinces of Indonesia, while in the Moluccas islands the husk of the durian fruit is used as fuel to smoke fish. The nectar and pollen of the durian flower that honeybees collect is an important honey source, but the characteristics of the honey are unknown.

Medicinal

In Malaysia, a decoction of the leaves and roots used to be prescribed as an antipyretic. The leaf juice is applied on the head of a fever patient. The most complete description of the medicinal use of the durian as remedies for fevers is a Malay prescription, collected by Burkill and Haniff in 1930. It instructs the reader to boil the roots of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis with the roots of Durio zibethinus, Nephelium longan, Nephelium mutabile and Artocarpus integrifolia, and drink the decoction or use it as a poultice.

In 1920's, Durian Fruit Products, Inc., of New York City launched a product called "Dur-India" as a health food supplement, selling at US$9 for a dozen bottles, each containing 63 tablets. The tablets allegedly contained durian and a species of the genus Allium from India and vitamin E. They were claimed to provide "more concentrated healthful energy in food form than any other product the world affords".

Durian typically contains (per 243 grams):

- Energy: 357 calories

- Fat: 13.0g

- Cholesterol: 0mg

- Sodium 5mg: 5mg

- Carbohydrates: 65.8g

- Dietary fibre: 9.2g

- Protein: 3.6g

Durian customs

In some Asian countries, durian is believed to have warming properties liable to cause excessive sweating. The traditional method to counteract this is to pour salted water into the empty shell of the fruit, after the pulp has been consumed, and drink it. An alternative method is to eat the durian in accompaniment with mangosteen that is considered to have cooling properties. People with high blood pressure or pregnant women are traditionally advised not to consume durian.

Another common local belief is that the durian is harmful when eaten along with alcoholic beverages. This belief can be traced back at least to 18th century when Rumphius declared that one should not drink alcohol after eating durians as it will cause indigestion and bad breath. J. D. Gimlette claimed in his Malay Poisons and Charm Cures (1929) that it was said that the durian fruit must not be eaten with brandy. In 1981, J. R. Croft wrote in his Bombacaceae: In Handbooks of the Flora of Papua New Guinea that a feeling of morbidity often follows the consumption of alcohol too soon after eating durian. Several medical investigations on the validity of this belief have been conducted, with varying conclusions.

The Javanese believe durian to have aphrodisiac qualities, and impose a strict set of rules on what may or may not be consumed with the durian or shortly after. The warnings against the supposed lecherous quality of this fruit soon spread to the West. The Swedenborgian mystic Herman Vetterling was particularly harsh on durian:

These erotomaniacs remind us of the Durian-eating Malays, who, because of the erotic properties of this fruit, become savage against anybody or anything that stands in their way of obtaining it. Fraser writes that upon eating it, men, monkeys, and birds 'are all aflame with erotic fire.' It is a blessing that this fruit is not obtainable in the West, because our store of sexual lunatics is already full to overflowing. We might perish in the foulest of mucks.

A durian falling on a person's head can cause serious injuries or death because it is heavy and armed with sharp thorns, and may fall from a significant height, so wearing a hardhat is recommended when collecting the fruit. For this reason the durian is sometimes called the most dangerous fruit in the world, along with its name in Vietnamese, sầu riêng, meaning "private sorrow". However, there are actually few reports of people getting hurt from falling durians. Durian farmers spread large nets under the trees to catch the fruit when it falls naturally, precisely because of the dangers of falling fruit; the nets are elastic and placed sufficiently high to prevent the fruit from hitting the ground. While there is a belief among locals that the durian "has eyes" and will not fall on a person, it is probably because fruits on a durian tree don't fall at the same time, which significantly decreases the possibility that it will hit a passerby. The Malay saying Durian runtuh, which can be translated as "Fallen Durian", is used to describe the sudden occurrence of a rare event. A similar saying in Indonesian, "mendapat durian runtuh", which translates to "getting a fallen durian", means receiving an unexpected luck or fortune.

Some durian are sold "thornless". These fruits have the thorns sheared off when young rather than being naturally thornless. Some durians really do have almost no spines, i.e. less than 5 mm high.

Cultural influence

The durian is commonly known as the "king of the fruits", a label that can be attributed to its formidable look and overpowering odour. Due to its unusual characteristics, the durian has been referenced or parodied in various cultural mediums. To foreigners the durian is often perceived as a symbol of revulsion. The 19th-century American journalist Bayard Taylor said of the fruit, "To eat it seems to be the sacrifice of self-respect." It can also be seen in the Japanese anime Dragon Ball, which features the loathsome villain Dodoria, whose name and appearance have been derived from the durian fruit. Dodoria, a large pink alien with short spikes on his head and forearms, was given an unattractive role which required slaughtering numerous characters and was eventually killed himself. The TV series Fear Factor featured the durian during a challenge in which participants were required to face the "Blender of Fear": a concoction of ground-up pig brains, rooster testes and cow eyes, and durian juice as the side beverage.

In its native southeastern Asia, however, the durian is an everyday food and portrayed in the local media in accordance with the different cultural perception it has in the region. The durian symbolised the subjective nature of ugliness and beauty in Hong Kong director Fruit Chan's 2000 film Durian Durian (榴槤飄飄, Liulian piao piao), and was a nick name for the reckless but lovable protagonist of the eponymous Singaporean TV comedy Durian King played by Adrian Pang. Likewise, the oddly shaped Esplanade building in Singapore is often called "The Durian" by locals. In Malaysia, there is a slice-of-life comic strip by C.W. Kee which has Sunday colour editions called It's A Durian Life.

One of the names Thailand contributed to the list of storm names for Western North Pacific tropical cyclones is 'Durian', and has been used twice thus far.

Being a fruit much loved by a variety of wild beasts, the durian sometimes signifies the long-forgotten animalistic aspect of humans, as in the legend of Orang Mawas, the Malaysian version of Bigfoot, and Orang Pendek, its Sumatran version, both of which have been claimed to feast on durians.

In accordance with its reputation as an aphrodisiac, the durian's flavour has been used in condoms. In Thailand, durian-flavoured condoms used to be sold at 7-Eleven nationwide. Indonesia began selling durian-flavoured condoms in 2003. According to the director of DKT Indonesia, the country's leading condom distributor, 150,000 of the durian-flavoured condoms were sold in their first week on the market.

References

- Publications

- Brown, Michael J. (1997). Durio — A Bibliographic Review. International Plant Genetic Resources Institute. 92-9043-318-3. Information All chapters (PDF format)

- Davidson, Alan (1999). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-211579-0.

- Huxley, A., ed. (1992). New RHS Dictionary of Gardening. Macmillan. ISBN 1-56159-001-0.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Marinelli, Janet, ed. (1998). Brooklyn Botanic Garden Gardener's Desk Reference. Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 0-8050-5095-7.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Morton, J. F. (1987). Fruits of Warm Climates. Florida Flair Books. ISBN 0-9610184-1-0. Full text Durian chapter

- Soepadmo, E. and Eow, B.K. (1977). The reproductive biology of Durian zibethinus. Gdns'Bull. Singapore 29: 25-34. (12.1.68)

- Whitten, Tony (2001). The Ecology of Sumatra. Periplus. ISBN 962-593-074-4.

- Notes

- "Botany and Production of Durian (Durio zibethinus) in Southeast Asia" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- Via durion, the Malay name for the plant. Oxford English Dictionary 1897; Huxley 1992.

- Brown, 1997.

- See Brown, p. 2; also, see Brown pp. 5–6 regarding whether Linnaeus or Murray is the correct authority for the binomial name. .pdf format

- Whitten, p. 329.

- Soepadmo and Eow, 1977.

- Bird-pollination of Three Durio Species (Bombacaceae) in a Tropical Rainforest in Sarawak, Malaysia, Takakazu Yumoto, American Journal of Botany 87(8): 1181–1188. 2000.

- Brown p. 77; also List of Malaysian durian clones from Durians Online (retrieved 5 March 2006.)

- Tropical fruit production and genetic resources in Southeast Asia: Identifying the priority fruit species - by M.B. Osman, Z.A. Mohamed, S. Idris and R. Aman

- ^ "Durio - A Bibliographic Review" Ipgri.cgiar.org. URL Accessd July 1, 2006.

- Watson, B.J. (1983). Durian. Fact Sheet No. 6. Rare Fruits Council of Australia.

- Production and trade figures from the FAO (2001). http://www.fao.org/DOCREP/MEETING/004/Y1982E.HTM. (Retrieved 4 March 2006.)

- Printed in volume 8 of William Jackson Hooker's Journal of Botany, 1856. Text online from the Alfred Russel Wallace page.

- Winokur, Jon (Editor) (2003). The Traveling Curmudgeon: Irreverent Notes, Quotes, and Anecdotes on Dismal Destinations, Excess Baggage, the Full Upright Position, and Other Reasons Not to Go There. Sasquatch Books. ISBN 1-57061-389-3.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) p. 102. - Davidson, p. 263.

- Brown p. 29. .pdf format

- Brown pp. 46–47 and Table 5 pp. 43–45.

- Marinelli, p.691.

- McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking (Revised Edition). Scribner. ISBN 0-684-80001-2. p. 379

- Brown.

- Brown.

- Davidson, p. 737.

- AgroForestryTree Database Worldagroforestry.org. URL Accessed July 10, 2006.

- Alim et al. 1994

- Banfield, E. J, (1911). My Tropic Isle. T. Fisher Unwin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Brown, 1997.

- Morton. "Keeping Quality".

- ^ Durian & Mangosteens Prositech.com. URL Accessed July 1, 2006.

- http://www.sabahtravelguide.com/culture/default.ASP?page=trad_cuisine

- http://www.ecst.csuchico.edu/~durian/rec/recipe.htm (URL accessed 3 March 2006)

- Morton.

- Singapore Science Centre — Question No. 18085: Is it true that durian seeds are poisonous? (URL accessed 20 March 2006)

- Morton.

- Crane, E. (ed.), 1976. Honey: A comprehensive survey. Bee Research Association.

- Morton.

- Burkill, I.H. and M. Haniff. 1930. Malay village medicine, prescriptions collected. Gardens Bulletin Straits Settlements 6: 165-321 (p. 176-177).

- Morton.

- Durian on Calorie count

- Washing hands with this water is also said to help remove the strong odour.

- Davidson, p. 263

- Vetterling, Herman (2003 (first printed in 1923)). Illuminate of Gorlitz or Jakob Bohme's Life and Philosophy, Part 3. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-4788-6.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) p. 1380. - The mangosteen, called as the "queen of fruits", is petite and mild in comparison. The mangosteen season coincides with that of the durian and is seen as a complement, which is probably how the mangosteen received the complementary title.

- http://www.confabulist.com/confabulist/2002/07/nature_most_fou.html

- Meaning of typhoon names (Japan Meteorological Agency)

- Stalking Bigfoot (pdf version) Hamiltonspectator.com. URL accessed 4 March 2006.

- Do 'orang pendek' really exist? Jambiexplorer.com. URL accessed 19 March 2006.

- Ziv, Daniel and Sharett, Guy (2004). Bangkok Inside Out. Equinox Publishing. ISBN 979-97964-6-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) p. 37. - "Now, durian condoms" Smh.com. URL accessed March 2006

External links

- Germplasm Resources Information Network: Durio

- Brooklyn Botanic Garden: Durian—The real Forbidden Fruit

- Durio zibethinus (Bombacaceae)

- Bats and Durians

- Durian Palace

- 2006 November, Severe Tropical Storm: Durian