This is an old revision of this page, as edited by JavierBustillos135 (talk | contribs) at 00:36, 27 February 2020 (→Suggestions of homosexuality or bisexuality). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:36, 27 February 2020 by JavierBustillos135 (talk | contribs) (→Suggestions of homosexuality or bisexuality)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article's factual accuracy is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help to ensure that disputed statements are reliably sourced. (February 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

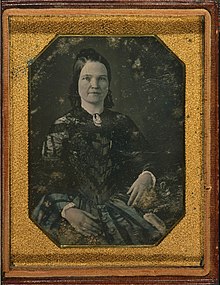

The heterosexuality of Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the 16th President of the United States, has been questioned by some activists. Lincoln was married to Mary Todd from November 4, 1842, until his death on April 15, 1865, and fathered four children with her.

Historical scholarship and debate

Marriage with Mary Todd Lincoln

Lincoln and Mary Todd met in Springfield in 1839 and became engaged in 1840. In what historian Allen Guelzo calls "one of the murkiest episodes in Lincoln's life", Lincoln called off his engagement to Mary Todd. It was at the same time as the collapse of a legislative program he had supported for years, the permanent departure of his best friend Joshua Speed from Springfield, and the proposal by John Stuart, Lincoln's law partner, to end their law practice. Lincoln is believed to have suffered something approaching clinical depression. In Lincoln's Preparation for Greatness: The Illinois Legislative Years, Paul Simon has a chapter covering the period, which Lincoln later referred to as "The Fatal First", or January 1, 1841. That was "the date on which Lincoln asked to be released from his engagement to Mary Todd". Simon explains that the various reasons given for the engagement being broken contradict one another. The incident was not fully documented, but Lincoln did become unusually depressed, which showed in his appearance, and Simon wrote that "it was traceable to Mary Todd". During this time, he avoided seeing Mary, causing her to comment that he "deems me unworthy of notice".

Jean H. Baker, historian and biographer of Mary Todd Lincoln, describes the relationship between Lincoln and his wife as "bound together by three strong bonds—sex, parenting and politics". In addition to the anti–Mary Todd bias of many historians, engendered by William Herndon's (Lincoln's law partner and early biographer) personal hatred of Mrs. Lincoln, Baker discounts historic criticism of the marriage. She says that contemporary historians have a basic misunderstanding of the changing nature of marriage and courtship in the mid-19th century, and attempt to judge the Lincoln marriage by modern standards.

Baker notes that "most observers of the Lincoln marriage have been impressed with their sexuality". Some "male historians" suggest that the Lincolns' sex life ended either in 1853 after their son Tad's difficult birth or in 1856 when they moved into a bigger house, but have no evidence for their speculations. Baker writes that there are "almost no gynecological conditions resulting from childbirth" other than a prolapsed uterus (which would have produced other noticeable effects on Mrs. Lincoln) that would have prevented intercourse, and in the 1850s, "many middle-class couples slept in separate bedrooms" as a matter of custom adopted from the English.

Far from abstaining from sex, Baker suggests that the Lincolns were part of a new development in America of smaller families; the birth rate declined from seven births to a family in 1800 to around 4 per family by 1850. As Americans separated sexuality from child bearing, forms of birth control such as coitus interruptus, long-term breast feeding, and crude forms of condoms and womb veils, available through mail order, were available and used. The spacing of the Lincoln children (Robert in 1843, Eddie in 1846, Willie in 1850, and Tad in 1853) is consistent with some type of planning and would have required "an intimacy about sexual relations that for aspiring couples meant shared companionate power over reproduction".

Herndon, Lincoln's law partner and biographer, attests to the depth of Lincoln's love for Ann Rutledge. An anonymous poem about suicide published locally three years after her death is widely attributed to Lincoln. In contrast, his courting of Mary Owens was diffident. In 1837, Lincoln wrote to her from Springfield to give her an opportunity to break off their relationship. Lincoln wrote to a friend in 1838: "I knew she was oversize, but now she appeared a fair match for Falstaff".

References

- "Abe Lincoln's Marriage", About.com

- Allen C. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President, (1999) pg. 97-98.

- ^ Paul Simon, Lincoln's Preparation for Greatness: The Illinois Legislative Years

- ^ Jean H. Baker, "Mary and Abraham: A Marriage" in The Lincoln Enigma, edited by Gabor Boritt, pgs. 49-55

- Baker pg. 50. Baker relies on (page 286, footnote 36) Linda Gordon's Woman's Body, Woman's Right: A Social History of Birth Control (1976) and Janet Brodie's Contraception and Abortion in 19th Century America (1994).

- "The Suicide Poem", The New Yorker, Eureka Dept., Jun 14, 2004

- Library of Congress: Collection Guides (online), Lincoln as Poet

- "Letter, Abraham Lincoln to Mary S. Owens reflecting the frustration of courtship, 16 August 1837". Library of Congress. (Abraham Lincoln Papers)

Further reading

- Hay, John; Nicolay, John George (1890). Abraham Lincoln: a History.

- "Volume 1". to 1856; strong coverage of national politics

- "Volume 2". (1832 to 1901) ; covers 1856 to early 1861; very detailed coverage of national politics; part of 10 volume "life and times" "written by Lincoln's top aides

- Michael F. Bishop, "All the President's Men", Washington Post February 13, 2005; Page BW03 online

- Book Questions Abraham Lincoln's Sexuality - Discovery Channel

- "The sexual life of Abraham Lincoln" by Andrew O'Hehir, Salon.com, Jan. 12, 2005 (requires subscription or viewing an ad before reading)

- The Lincoln Bedroom: A Critical Symposium Claremont Review of Books, Summer 2005

- Exploring Lincoln's Loves Scott Simon in conversation with Lincoln scholars Michael Chesson and Michael Burlingame. National Public Radio, February 12, 2005

- We Are Lincoln Men Margaret Warner speaks with Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Herbert Donald about his book, We Are Lincoln Men: Abraham Lincoln and His Friends. Public Broadcasting Service, November 26, 2003

- Jay Hatheway. American Historical Review 111#2 (April 2006) - An Edgewood College history professor's book review of C.A. Tripp's The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln online

- Mr. Lincoln and Friends: Joshua F. Speed