This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Riapress (talk | contribs) at 05:10, 12 January 2007 (→External links: added link referenced in the discussion page for thoreau). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

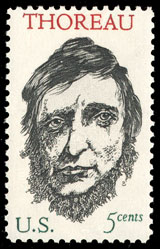

Revision as of 05:10, 12 January 2007 by Riapress (talk | contribs) (→External links: added link referenced in the discussion page for thoreau)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817 – May 6, 1862; born David Henry Thoreau) was an American author, naturalist, transcendentalist, tax resister, development critic, and philosopher who is most well-known for Walden, a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and his essay, Civil Disobedience, an argument for individual resistance to civil government in moral opposition to an unjust state.

Thoreau’s books, articles, essays, journals, and poetry total over 20 volumes. He was famous for writing: “If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer.” Among his lasting contributions were his writings on natural history and philosophy, where he anticipated the methods and findings of ecology and environmental history, two sources of modern day environmentalism.

He was a lifelong abolitionist, delivering lectures that attacked the Fugitive Slave Law while praising the writings of Wendell Phillips and defending the abolitionist John Brown. Thoreau's philosophy of nonviolent resistance influenced the political thoughts and actions of such later figures as the pacifist Leo Tolstoy, the separatist Mohandas K. Gandhi, and the civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. Some anarchists claim Thoreau as a predecessor, but "Civil Disobedience" supports improving rather than abolishing government: "I ask for, not at once no government, but at once a better government."

Early Years: 1817-1844

David Henry Thoreau was born in Concord, Massachusetts to John Thoreau and Cynthia Dunbar. His paternal grandfather was of French origin and born on the Isle of Jersey. David Henry was named after a recently deceased paternal uncle, David Thoreau. He did not become “Henry David” until after college, although he never petitioned to make a legal name change. He had two older siblings, Helen and John Jr., and a younger sister, Sophia. Thoreau’s birthplace still exists on Virginia Road in Concord and is the focus of current preservation efforts. The house is original, but it now stands about 100 yards away from its first site.

Bronson Alcott noted in his journal that Thoreau pronounced his family name , stressing the first syllable, not the second as is common today. A Concord variant is , like the standard American pronunciation of the word “thorough.” In appearance he was homely, with a nose that he called “my most prominent feature” (Cape Cod). Of his face, Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote: “ is as ugly as sin, long-nosed, queer-mouthed, and with uncouth and rustic, though courteous manners, corresponding very well with such an exterior. But his ugliness is of an honest and agreeable fashion, and becomes him much better than beauty.”

Thoreau studied at Harvard between 1833 and 1837. He lived in Hollis Hall and took courses in rhetoric, classics, philosophy, mathematics, and science. Legend states that Thoreau refused to pay the five-dollar fee for a Harvard diploma. In fact, the Masters’ degree he declined to purchase had no academic merit: Harvard College offered it to graduates “who proved their physical worth by being alive three years after graduating, and their saving, earning, or inheriting quality or condition by having Five Dollars to give the college” (Thoreau's Diploma). His comment was: “Let every sheep keep its own skin.”

During a leave of absence from Harvard in 1835, Thoreau taught school in Canton, Massachusetts. After graduating in 1837, he joined the faculty of Concord Academy, but he refused to administer corporal punishment and the school board soon dismissed him. He and his brother John then opened a grammar school in Concord in 1838. They introduced several progressive concepts, including nature walks and visits to local shops and businesses. The school ended when John became fatally ill from tetanus in 1841.

Upon graduation Thoreau returned home, where he befriended Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson took a paternal and at times patronizing interest in Thoreau, advising the young man and introducing him to a circle of local writers and thinkers, including Ellery Channing, Margaret Fuller, Bronson Alcott, Nathaniel Hawthorne and his son Julian, who was a boy at the time. Of the many prominent authors who lived in Concord, Thoreau was the only town native. Emerson referred to him as the man of Concord.

Emerson constantly urged Thoreau to contribute essays and poems to a quarterly periodical, The Dial, and Emerson lobbied with editor Margaret Fuller to publish those writings. Thoreau’s first essay published there was Natural History of Massachusetts; half book review, half natural history essay, it appeared in 1842. It consisted of revised passages from his journal, which he had begun keeping at Emerson’s suggestion. The first entry on October 22, 1837 reads, “‘What are you doing now?’ he asked. ‘Do you keep a journal?’ So I make my first entry today.”

Thoreau was a philosopher of nature and its relation to the human condition. In his early years he followed Transcendentalism, a loose and eclectic idealist philosophy advocated by Emerson, Fuller, and Alcott. They held that an ideal spiritual state transcends, or goes beyond, the physical and empirical, and that one achieves that insight via personal intuition rather than religious doctrine. In their view, Nature is the outward sign of inward spirit, expressing the “radical correspondence of visible things and human thoughts,” as Emerson wrote in Nature (1836).

In 1841 Thoreau joined the Emerson household to serve as children’s tutor, editorial assistant, and repair man/gardener. For a few months in 1843, he moved to the home of William Emerson on Staten Island, tutoring the family sons while writing for New York periodicals, aided in part by his future literary representative Horace Greeley. Thoreau returned to Concord and had a restless period: he worked in the family pencil shop, accidentally burned a large patch of local forest, and searched for a farm to buy or lease. He wanted to support himself while having enough solitude to write a first book.

Walden Years: 1845–1847

Thoreau embarked on a two-year experiment in simple living on July 4, 1845, when he moved to a small self-built house on land owned by Emerson in a second-growth forest around the shores of Walden Pond. The house was not in wilderness but at the edge of town, 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from his family home.

On one trip into town, he ran into the local tax collector who asked him to pay six years of delinquent poll taxes. Thoreau refused because of his opposition to the Mexican-American War and slavery, and he spent a night in jail because of this refusal. (The next day Thoreau was freed, over his protests, when his aunt paid his taxes.) His later essay on this experience and his reasons for taking this stand, Civil Disobedience, influenced such political theorists and activists as Leo Tolstoy, Mohandas Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

At Walden Pond, he completed a first draft of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, an elegy to his brother, John, that described their 1839 trip to the White Mountains, with many digressions that include extracts of his early writings. Thoreau did not find a publisher for this book, and Emerson urged Thoreau to publish at his own expense. Thoreau did so with Munroe, Emerson’s own publisher, who did little to publicize the book. Its failure put Thoreau into debt that took years to pay off, and Emerson’s flawed advice caused a schism between the friends that never entirely healed.

In August of 1846, Thoreau briefly left Walden to make a trip to Mount Katahdin in Maine, a journey later recorded in “Ktaadn,” the first part of The Maine Woods.

Thoreau left Walden Pond on September 6, 1847. Over several years, he worked to pay off his debts and also continuously revised his manuscript. In 1854, he published Walden: or, Life in the Woods, recounting the two years, two months, and two days he had spent at Walden Pond. The book compresses that time into a single calendar year, using the passage of four seasons to symbolize human development. Part memoir and part spiritual quest, Walden at first won few admirers, but today critics regard it as a classic American book that explores natural simplicity, harmony, and beauty as models for just social and cultural conditions.

Late Years: 1851-1858

In 1851, Thoreau became increasingly fascinated with natural history and travel/expedition narratives. He read avidly on botany and often wrote observations on this topic into his Journal. He greatly admired William Bartram, and Charles Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle. He kept detailed observations on Concord's nature lore, recording everything from how the fruit ripened over time to the fluctuating depths of Walden Pond and the days certain birds migrated. The point of this task was to “anticipate” the seasons of nature, in his words.

He became a land surveyor, “travelling a good deal in Concord,” and writing natural history observations about the 26 mile² (67 km²) township in his Journal, a two-million word document he kept for 24 years. He also kept a series of separate notebooks, and these observations became the source for Thoreau's late natural history writings, such as Autumnal Tints, The Succession of Trees, and Wild Apples, an essay bemoaning the destruction of indigenous and wild apple species.

Until the 1970s, Thoreau’s late pursuits were dismissed by literary critics as amateur science and declined philosophy. With the rise of environmental history and ecocriticism, several new readings of this matter began to emerge, showing Thoreau to be both a philosopher and an analyst of ecological patterns in fields and woodlots. For instance, his late essay, "The Succession of Forest Trees," shows that he used experimentation and analysis to explain how forests regenerate after fire or human destruction, through dispersal by seed-bearing winds or animals.

He was an early advocate of recreational hiking and canoeing, of conserving natural resources on private land, and of preserving wilderness as public land. Thoreau was also one of the first American supporters of Darwin's theory of evolution. Although not a strict vegetarian, Thoreau ate relatively little meat and advocated vegetarianism as a means of self-improvement.

Thoreau neither rejected civilization nor fully embraced wilderness. Instead he sought a middle ground, the pastoral realm that integrates both nature and culture. The wildness he enjoyed was the nearby swamp or forest, and he preferred “partially cultivated country.” His idea of being “far in the recesses of the wilderness” of Maine was to “travel the logger’s path and the Indian trail,” but he also hiked on pristine untouched land.

Thoreau had a natural gift for mechanics and he worked at his family’s pencil factory throughout most of his adult life. According to Henry Petroski, Thoreau rediscovered how to make a good pencil out of inferior graphite by using clay as the binder; this invention improved upon graphite found in New Hampshire in 1821 by Charles Dunbar. (The process of mixing graphite and clay, known as the Conté process, was patented by Nicolas-Jacques Conté in 1795) Later, Thoreau converted the factory to producing plumbago (graphite), used to ink typesetting machines. Frequent contact with minute particles of graphite may have weakened his lungs.

He traveled to Quebec once, Cape Cod four times, and Maine three times; these landscapes inspired his “excursion” books, A Yankee in Canada, Cape Cod, and The Maine Woods, in which travel itineraries frame his thoughts about geography, history and philosophy. Other travels took him southwest to Philadelphia and New York City in 1854, and west across the Great Lakes region in 1861, visiting Niagara Falls, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, and Mackinac Island.

Final Years: 1859-1862

Thoreau first contracted tuberculosis in 1835 and suffered from it sporadically over his life. In 1859, following a late night excursion to count the rings of tree stumps during a rain storm, he became ill with bronchitis. His health declined over three years with brief periods of remission, until he eventually became bedridden. Recognizing the terminal nature of his disease, Thoreau spent his last years revising and editing his unpublished works, particularly Excursions and The Maine Woods and petitioning publishers to print revised editions of A Week and Walden. He also wrote letters and Journal entries until he became too weak to continue. His friends were alarmed at his diminished appearance and fascinated by his tranquil acceptance of death. When his aunt Louisa asked him in his last weeks if he had made his peace with God, Thoreau responded quite simply: “I did not know we had ever quarrelled.” He died on May 6, 1862 at the age of 44.

Originally buried in the Dunbar family plot, he and members of his immediate family were eventually moved to Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, Massachusetts. Emerson wrote the eulogy spoken at his funeral. Thoreau’s best friend Ellery Channing published his first biography, Thoreau the Poet-Naturalist, in 1873, and Channing and another friend Harrison Blake edited some poems, essays, and journal entries for posthumous publication in the 1890s. Thoreau’s Journal, often mined but largely unpublished at his death, first appeared in 1906 and helped to build his modern reputation. A new and greatly expanded edition of the Journal is underway, published by Princeton University Press. Today, Thoreau is regarded as one of the foremost American writers, both for the modern clarity of his prose style and the prescience of his views on nature and politics. His memory is honored by the international Thoreau Society, the oldest and largest society devoted to an American author.

Harrison Blake

Thoreau first received a letter from Harrison Blake, an ex-minister (Unitarian) widower of Worcester, Massachusetts, in March of 1848. Thus began a correspondence which lasted at least until May 3, 1861. Only Blake's first letter remains, but forty-nine of Thoreau's replies have been recovered. Harrison Blake, a year older than Thoreau, heard of Thoreau's experiment at Walden only six months after Thoreau had returned, but still six years before the book Walden was to be published. And while Thoreau was not yet widely recognized for his philosophical outlook, initiating a discourse with the author was strictly for that reason. Blake's first letter makes it clear that he seeks a spiritual mentor, and Thoreau's replies reveal that he was eager to fill the role. After the death of Sophia Thoreau, Harrison Blake inherited Thoreau's papers, and Blake was the first to publish extracts from the Journal.

Criticisms

Thoreau was not without his critics. Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson judged Thoreau’s endorsement of living alone in natural simplicity, apart from modern society, to be a mark of effeminacy:

…Thoreau’s content and ecstasy in living was, we may say, like a plant that he had watered and tended with womanish solicitude; for there is apt to be something unmanly, something almost dastardly, in a life that does not move with dash and freedom, and that fears the bracing contact of the world. In one word, Thoreau was a skulker. He did not wish virtue to go out of him among his fellow-men, but slunk into a corner to hoard it for himself. He left all for the sake of certain virtuous self-indulgences.

However, English novelist George Eliot, writing in the Westminster Review, characterized such critics as uninspired and narrow-minded:

People—very wise in their own eyes—who would have every man’s life ordered according to a particular pattern, and who are intolerant of every existence the utility of which is not palpable to them, may pooh-pooh Mr. Thoreau and this episode in his history, as unpractical and dreamy.

Throughout the 19th century, Thoreau was dismissed as a cranky provincial, hostile to material progress. In a later era, his devotion to the causes of abolition, Native Americans, and wilderness preservation have marked him as a visionary.

Influence

Thoreau’s writings had far reaching influences on many public figures. Political leaders and reformers like Mahatma Gandhi, President John F. Kennedy, Civil rights activist Martin Luther King, Jr., Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, and Russian author Leo Tolstoy all spoke of being strongly affected by Thoreau’s work, particularly Civil Disobedience. So did many artists and authors including Edward Abbey, Willa Cather, Marcel Proust, William Butler Yeats, Sinclair Lewis, Ernest Hemingway, E. B. White and Frank Lloyd Wright and naturalists like John Burroughs, John Muir, Edwin Way Teale, Joseph Wood Krutch and David Brower. Anarchist and feminist Emma Goldman also appreciated Thoreau, and referred to him as “the greatest American anarchist”.

Thoreau's works

- A Walk to Wachusett (1842)

- A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849)

- On the Duty of Civil Disobedience (1849)

- Slavery in Massachusetts (1854)

- Walden (1854)

- A Plea for Captain John Brown (1860)

- Excursions (1863)

- Life Without Principle

- The Maine Woods (1864)

- Cape Cod (1865)

- Early Spring in Massachusetts (1881)

- Summer (1884)

- Winter (1888)

- Autumn (1892)

- Miscellanies (1894)

- Journal of Henry David Thoreau (1906)

- Of Woodland Pools, Spring-holes & Ditches (2005)

- Henry David Thoreau, et al., The Classics of Style. The American Academic Press, 2006.

Online texts

- Thoreau's Life & Writings (at the Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods)

- Autumnal Tints - courtesy of Wikisource.

- Cape Cod - The Thoreau Reader

- On the Duty of Civil Disobedience - A well-footnoted version.

- On the Duty of Civil Disobedience - courtesy of Wikisource.

- The Highland Light - courtesy of Wikisource.

- The Landlord - courtesy of Wikisource.

- Life Without Principle - courtesy of Wikisource.

- The Maine Woods - The Thoreau Reader

- Night and Moonlight - courtesy of Wikisource.

- A Plea for Captain John Brown

- A Plea for Captain John Brown - an annotated version

- Slavery in Massachusetts - The Thoreau Reader

- Walden

- Walden - The Thoreau Reader

- Walking - courtesy of Wikisource.

- Walking

- A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers

- Wild Apples: The History of the Apple Tree

- Works by Henry David Thoreau at Project Gutenberg

- A Walk To Wachusett - The Walden Woods Project

References

- Bode, Carl. Best of Thoreau's Journals. Southern Illinois University Press. 1967.

- Botkin, Daniel. No Man's Garden.

- Dassow Walls, Laura. Seeing New Worlds: Henry David Thoreau and 19th Century Science. University of Wisconsin Press. 1995.

- Dean, Bradley P. ed., Letters to a Spiritual Seeker. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004.

- Harding, Walter. The Days of Henry Thoreau. Princeton University Press, 1982.

- Howarth, William. The Book of Concord: Thoreau's Life as a Writer. Viking Press, 1982.

- Meyerson, Joel et al. The Cambridge Companion to Henry David Thoreau. Cambridge University Press. 1995.

- Nash, Roderick. Henry David Thoreau, Philosopher.

- Parrington, Vernon. Main Current in American Thought. V 2 online. 1927.

- Petroski, Henry. H. D. Thoreau, Engineer. American Heritage of Invention and Technology, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 8-16.

- Stevenson, Robert Louis. Henry David Thoreau: His Character and Opinions. Cornhill Magazine. June 1880.

External links

- Who He Was & Why He Matters - by Randall Conrad

- The Birthplace of Thoreau

- The Blog of Henry David Thoreau

- The Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods

- Thoreau David Thoreau ("The Transcendentalists")

- The American Transcendentalist Web

- Thoreau Project at Calliope

- The Thoreau Society

- The Thoreau Edition

- The Thoreau Reader

- Concordance to works of Thoreau at Victorian Literary Studies Archive

- John Updike, "A Sage for All Seasons" - courtesy of the UK Guardian, an edited extract from the introduction to Updike's new edition of Walden

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Poems of Thoreau

- Henry Thoreau: Transcendental Economist from Vernon L. Parrington's Main Currents in American Thought

- Stephen Ells' Thoreau research page

- The European Thoreau web page: multilingual resources for Thoreauvians

- Free typeset PDF ebook of Walden designed for printing at home

- 1817 births

- 1862 deaths

- American abolitionists

- American autodidacts

- American environmentalists

- American essayists

- American naturalists

- American philosophers

- American poets

- American tax resisters

- American teetotalers

- American travel writers

- American Unitarians

- Civil disobedience

- Deaths by tuberculosis

- French Americans

- Historical people of U.S. natural history

- Massachusetts writers

- Nonviolence

- Transcendentalism

- Americans with Huguenot ancestry

- People from Massachusetts