This is an old revision of this page, as edited by GKFX (talk | contribs) at 12:10, 24 December 2021 (Remove Template:Columns: being deleted (via WP:JWB)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 12:10, 24 December 2021 by GKFX (talk | contribs) (Remove Template:Columns: being deleted (via WP:JWB))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Slavic goddess of rain, wife of Perun. For the town in Ethiopia, see Dodola, Ethiopia.| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Dodola and Perperuna" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

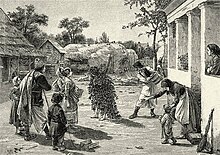

Dodola (also spelled Doda, Dudulya and Didilya), also known under the names for butterfly: Paparuda, Peperuda, Perperuna or Preperuša, is a pagan tradition found in the Balkans. The central character of the ceremony is usually an orphan girl, less often, a boy. Wearing a skirt made of fresh green knitted vines and small branches, the girl born after the death of her father, the last girl child of the mother (if the mother subsequently gives birth to another child, great misfortunes are expected in the village), sings and dances through the streets of the village, stopping at every house, where the hosts sprinkle water on her. The ritual is associated with a particular tune to which a particular dance is performed, not only by the girl, but also by the villagers who follow her through the streets, shouting their encouragement.

According to some interpretations, Dodola is a Slavic goddess of rain, and the wife of the supreme deity Perun (god of thunder in the Slavic pantheon). Slavs believed that when Dodola milks her heavenly cows, the clouds, it rains on earth. Each spring Dodola is said to fly over woods and fields, and spread vernal greenery, decorating the trees with blossoms.

Names

The custom is known by the names Dodola (dodole, dudula, dudulica, dodolă) and Perperuna (peperuda, peperuna, peperona, perperuna, prporuša, preporuša, paparudă, pirpirună). Both names are used by the South Slavs, Romanians, Albanians and northern Greeks. Albanians also use the name Rona and the masculine name Dordolec (durdulec).

The name Perperuna is identified as the reduplicated feminine derivative of the name of the god Perun (per-perun-a). Sorin Paliga suggested that it was a divinity from the local Thracian substratum. The name Dodola is possibly cognate with the Lithuanian dundulis, a word for thunder and another name of the Baltic thunder-god Perkūnas.

D. Decev compared the word "dodola" (also dudula, dudulica, etc.) with Thracian anthroponyms (personal names) and toponyms (place names), such as Doidalsos, Doidalses, Dydalsos, Dudis, Doudoupes, etc. Paliga argued that based on this, the custom most likely originated from the Thracians.

A much more likely explanation for the variations of the name Didilya is that this is a title for the spring goddess Lada/Lela that got turned into the "name" of a goddess. Ralston explains that dido, means “great” and is usually used in conjunction with the spring god Lado.

Ritual

The first written description of the custom was left by the Bulgarian hieromonk Spiridon Gabrovski in 1792. He tells how in times of drought young boys and girls would dress one of their number in a net and a wreath of leaves in the likeness of Perun or Peperud, whom Spiridon mistakenly believed to be an old Bulgarian ruler. They would then walk in procession around the houses, singing, dancing and pouring water over each other. Villagers would give them money, which they later used to buy food and drink to celebrate in Perun’s honor.

South Slavs used to organise the Dodole (or Perperuna) festival in times of drought, where they worshipped the goddess and prayed to her for rain. In the ritual, young women sing specific songs to Dodola, accompanying it by a dance, while covered in leaves and small branches. In Croatia Dodole is often performed by folklore groups.

In folklore of Turopolje on the holidays of St. Juraj called Jurjevo five most beautiful maidens are picked to portray Dodola goddesses in leaf-dresses and sing for the village till the end of the holiday.

Serbian ritual chant sung by youngsters going through the village in the dry, summer months.

| Naša dodo Boga moli, | Our dodo prays to God, |

| Da orosi sitna kiša, | To drizzle a little rain, |

| Oj, dodo, oj dodole! | Oh, dodo, oh dodole! |

| Mi idemo preko sela, | We're going across the village, |

| A kišica preko polja, | And the rain across the field, |

| Oj, dodo, oj, dodole! | Oh, dodo, oh, dodole! |

Dodole in Macedonia

The oldest record for Dodole rituals in Macedonia is the song "Oj Ljule" from Struga region, recorded in 1861.

| Macedonian | Transliteration |

|---|---|

|

Отлетала преперуга, ој љуле, ој! От орача на орача, От копача на копача, От режача на режача; Да заросит ситна роса Ситна роса берикетна И по поле и по море; Да се родит с' берикет С' берикет винo-жито; Чеинците до гредите, Јачмените до стреите, Леноите до пojacи, Уроите до колена; Да се ранет сиромаси. Дрвете не со осито, Да је ситна година; Дрвете не со ошница, Да је полна кошница; Дрвете не со јамаче, Да је тучна година. "ој љуле, ој!" is repeated in every verse |

Otletala preperuga, oj ljule, oj! Ot oracha na oracha, Ot kopacha na kopacha, Ot rezhacha na rezhacha; Da zarosit sitna rosa Sitna rosa beriketna I po pole i po more; Da se rodit s' beriket S' beriket vino-zhito; Cheincite do gredite, Jachmenite do streite, Lenoite do pojasi, Uroite do kolena; Da se ranet siromasi. Drvete ne so osito, Da je sita godina; Drvete ne so oshnica, Da ja polna koshnica; Drvete ne so jamache, Da je tuchna godina. "oj ljule, oj!" is repeated in every verse |

The Dodola rituals in Macedonia were actively held until the 1960s.

Bulgarian traditional Peperuda song with literal translation;

| Летела е пеперуда, | A butterfly flew, |

| дай, Боже, дъжд, (2) | give, God, rain, (2) |

| от ораче на копаче, | from plowman to digger, |

| да се роди жито, просо, | to give birth to wheat, millet |

| жито, просо и пшеница, | wheat, millet and wheat |

| да се ранят сирачета, | to feed orphans, |

| сирачета, сиромаси. | orphans, the poor. |

See also

References

- Jakobson, Roman (1955). "While Reading Vasmer's Dictionary" In: WORD, 11:4: p. 616.

- Radosavljevich, Paul Rankov (1919). Who are the Slavs?: A Contribution to Race Psychology. Original from the University of Michigan: The Gorham Press. p. 19.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, p. 235.

- ^ Sorin Paliga: "Influenţe romane și preromane în limbile slave de sud" .pdf Archived December 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- D. Decev, Die thrakischen Sprachreste, Wien: R.M. Rohrer, 1957, pp. 144, 151

- Ralston. The Songs of the Russian People. p. 28

- Габровски, Спиридон Иеросхимонах (1900). История во кратце о болгарском народе славенском. Сочинися и исписа в лето 1792. София: изд. Св. Синод на Българската Църква. pp. 14.

- Miladinovci (1962). Зборник (PDF). Skopje: Kočo Racin. p. 462. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-16.

- Veličkovska, Rodna (2009). Музичките дијалекти во македонското традиционално народно пеење : обредно пеење [Musical dialects in the Macedonian traditional folk singing : ritual singing] (in Macedonian). Skopje: Institute of folklore "Marko Cepenkov". p. 45.

Bibliography

- Puhvel, Jaan (1987). Comparative Mythology. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-3938-2.

Further reading

- "The Paparude and Kalojan". In: Beza, Marcu. Paganism in Romanian Folklore. London: J.M.Dent &Sons LTD. 1928. pp. 27-36.