This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Autist4lyfe (talk | contribs) at 20:21, 24 January 2022. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:21, 24 January 2022 by Autist4lyfe (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Australian national holiday

| Australia Day | |

|---|---|

Sydney Harbour on Australia Day, 2004 Sydney Harbour on Australia Day, 2004 | |

| Also called | Survival Day, Invasion Day |

| Observed by | Australian citizens, residents and expatriates |

| Type | National |

| Significance | Date of Australia becoming a nation |

| Observances | Family gatherings, fireworks, picnics and barbecues; parades; citizenship ceremonies; Australia Day honours; Australian of the Year presentation |

| Date | 26 January |

| Frequency | Annual |

Australia Day is the official national day of Australia. Observed annually on 26 January, it marks the 1788 landing of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove and raising of the Union Flag by Arthur Phillip following days of exploration of Port Jackson in New South Wales. In present-day Australia, celebrations aim to reflect the diverse society and landscape of the nation and are marked by community and family events, reflections on Australian history, official community awards and citizenship ceremonies welcoming new members of the Australian community.

The meaning and significance of Australia Day has evolved and been contested over time, and not all states have celebrated the same date as their date of historical significance. The date of 26 January 1788 marked the proclamation of British sovereignty over the eastern seaboard of Australia (then known as New Holland). Although it was not known as Australia Day until over a century later, records of celebrations on 26 January date back to 1808, with the first official celebration of the formation of New South Wales held in 1818. On New Year's Day 1901, the British colonies of Australia formed a federation, marking the birth of modern Australia. A national day of unity and celebration was looked for. It was not until 1935 that all Australian states and territories adopted use of the term "Australia Day" to mark the date, and not until 1994 that the date was consistently marked by a public holiday on that day by all states and territories. Unofficially or historically, the date has also been variously named Anniversary Day, Foundation Day and ANA Day.

In contemporary Australia, the holiday is marked by the presentation of the Australian of the Year Awards on Australia Day Eve, announcement of the Australia Day Honours list and addresses from the governor-general and prime minister. It is an official public holiday in every state and territory. With community festivals, concerts and citizenship ceremonies, the day is celebrated in large and small communities and cities around the nation. Australia Day has become the biggest annual civic event in Australia.

Indigenous Australian events are now included. However, since at least 1938, the date of Australia Day has also been marked by some Aboriginal Australians and supporters mourning what is seen as the invasion of the land by the British and the start of colonisation, protesting its celebration as a national holiday. Invasion Day, Survival Day, or Day of Mourning is observed by many as a counter-observance on 26 January, with calls for the date to be changed or the holiday to be abolished entirely. Support for changing the date has remained a minority position, according to a a poll by the politically conservative Institute of Public Affairs (IPA) in December 2020.

History

Arrival of the First Fleet: 1788

Main article: First FleetOn 13 May 1787 a fleet of 11 ships, which came to be known as the First Fleet, was sent by the British Admiralty from England to New Holland. Under the command of Naval Captain Arthur Phillip, the fleet sought to establish a penal colony at Botany Bay on the coast of New South Wales, which had been explored and claimed by Lieutenant James Cook in 1770. The settlement was seen as necessary because of the loss of the Thirteen Colonies in North America. The Fleet arrived between 18 and 20 January 1788, but it was immediately apparent that Botany Bay was unsuitable.

On 21 January, Phillip and a few officers travelled to Port Jackson, 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) to the north, to see if it would be a better location for a settlement. They stayed there until 23 January; Phillip named the site of their landing Sydney Cove, after the Home Secretary, Thomas Townshend, 1st Viscount Sydney. They also made contact with the local Aboriginal people.

They returned to Botany Bay on the evening of 23 January, when Phillip gave orders to move the fleet to Sydney Cove the next morning, 24 January. That day, there was a huge gale blowing, making it impossible to leave Botany Bay, so they decided to wait till the next day, 25 January. However, during 24 January, they spotted the ships Astrolabe and Boussole, flying the French flag, at the entrance to Botany Bay; they were having as much trouble getting into the bay as the First Fleet was having getting out.

On 25 January the gale was still blowing; the fleet tried to leave Botany Bay, but only HMS Supply made it out, carrying Arthur Phillip, Philip Gidley King, some marines and about 40 convicts; they anchored in Sydney Cove in the afternoon. Meanwhile, back at Botany Bay, Captain John Hunter of HMS Sirius made contact with the French ships, and he and the commander, Captain de Clonard, exchanged greetings. Clonard informed Hunter that the fleet commander was Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse. Sirius successfully cleared Botany Bay, but the other ships were in great difficulty. Charlotte was blown dangerously close to rocks, Friendship and Prince of Wales became entangled, both ships losing booms or sails, Charlotte and Friendship collided, and Lady Penrhyn nearly ran aground. Despite these difficulties, all the remaining ships finally managed to clear Botany Bay and sail to Sydney Cove on 26 January. The last ship anchored there at about 3 pm.

So it was on 26 January that a landing was made at Sydney Cove and clearing of the ground for an encampment immediately began. Then, according to Phillip's account:

In the evening of the 26th the colours were displayed on shore, and the Governor, with several of his principal officers and others, assembled round the flag-staff, drank the king's health, and success to the settlement, with all that display of form which on such occasions is esteemed propitious, because it enlivens the spirits, and fills the imagination with pleasing presages.

— The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay

The formal establishment of the Colony of New South Wales did not however occur on 26 January as is commonly assumed. It did not occur until 7 February 1788, when the formal proclamation of the colony and of Arthur Phillip's governorship were read out. The vesting of all land in the reigning monarch King George III also dates from 7 February 1788.

1788–1838

Although there was no official recognition of the colony's anniversary, with the New South Wales Almanacks of 1806 and 1808 placing no special significance on 26 January, by 1808 the date was being used by the colony's immigrants, especially the emancipated convicts, to "celebrate their love of the land they lived in" with "drinking and merriment". The 1808 celebrations followed this pattern, beginning at sunset on 25 January and lasting into the night, the chief toast of the occasion being Major George Johnston. Johnston had the honour of being the first officer ashore from the First Fleet, having been carried from the landing boat on the back of convict James Ruse. Despite suffering the ill-effects of a fall from his gig on the way home to Annandale, Johnston led the officers of the New South Wales Corps in arresting Governor William Bligh on the following day, 26 January 1808, in what became known as the "Rum Rebellion".

Almanacs started mentioning "First Landing Day" or "Foundation Day" and successful immigrants started holding anniversary dinners. In 1817 The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser reported on one of these unofficial gatherings at the home of Isaac Nichols:

On Monday the 27th ult. a dinner party met at the house of Mr. Isaac Nichols, for the purpose of celebrating the Anniversary of the Institution of this Colony under Governor Philip, which took place on 26 Jan. 1788, but this year happening upon a Sunday, the commemoration dinner was reserved for the day following. The party assembled were select, and about 40 in number. At 5 in the afternoon dinner was on the table, and a more agreeable entertainment could not have been anticipated. After dinner a number of loyal toasts were drank, and a number of festive songs given; and about 10 the company parted, well gratified with the pleasures that the meeting had afforded.

— The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser

1818 was the 30th anniversary of the founding of the colony, and Governor Lachlan Macquarie chose to acknowledge the day with the first official celebration. The governor declared that the day would be a holiday for all government workers, granting each an extra allowance of "one pound of fresh meat", and ordered a 30-gun salute at Dawes Point – one for each year that the colony had existed. This began a tradition that was retained by the Governors that were to follow.

Foundation Day, as it was known at the time, continued to be officially celebrated in New South Wales, and in doing so became connected with sporting events. One of these became a tradition that is still continued today: in 1837 the first running of what would become the Australia Day regatta was held on Sydney Harbour. Five races were held for different classes of boats, from first class sailing vessels to watermen's skiffs, and people viewed the festivities from both onshore and from the decks of boats on the harbour, including the steamboat Australian and the Francis Freeling—the latter running aground during the festivities and having to be refloated the next day. Happy with the success of the regatta, the organisers resolved to make it an annual event. However, some of the celebrations had gained an air of elitism, with the "United Australians" dinner being limited to those born in Australia. In describing the dinner, the Sydney Herald justified the decision, saying:

The parties who associated themselves under the title of "United Australians" have been censured for adopting a principle of exclusiveness. It is not fair so to censure them. If they invited emigrants to join them they would give offence to another class of persons – while if they invited all they would be subject to the presence of persons with whom they might not wish to associate. That was a good reason. The "Australians" had a perfect right to dine together if they wished it, and no one has a right to complain.

— The Sydney Herald

The following year, 1838, was the 50th anniversary of the founding of the colony, and as part of the celebrations Australia's first public holiday was declared. The regatta was held for a second time, and people crowded the foreshores to view the events, or joined the five steamers (Maitland, Experiment, Australia, Rapid, and the miniature steamer Firefly) to view the proceedings from the water. At midday 50 guns were fired from Dawes' Battery as the Royal Standard was raised, and in the evening rockets and other fireworks lit the sky. The dinner was a smaller affair than the previous year, with only 40 in attendance compared to the 160 from 1837, and the anniversary as a whole was described as a "day for everyone".

1839–1935

Prior to 1888, 26 January was very much a New South Wales affair, as each of the colonies had its own commemoration for its founding. In Tasmania, Regatta Day occurred initially in December to mark the anniversary of the landing of Abel Tasman. South Australia celebrated Proclamation Day on 28 December. Western Australia had its own Foundation Day (now Western Australia Day) on 1 June.

The decision to mark the occasion of the First Fleet’s arrival in 1788 at Sydney Cove and Captain Arthur Phillip’s proclamation of British sovereignty over the eastern continent on January 26 was first made outside NSW by the Australian Natives' Association (ANA), a group of white "native-born" middle class men formed in Victoria in 1871. They dubbed the day "ANA Day".

In 1888, all colonial capitals except Adelaide celebrated "Anniversary Day". In 1910, South Australia adopted 26 January as "Foundation Day", to replace another holiday known as Accession Day, which had been held on 22 January to mark the accession to the throne of King Edward VII, who died in May 1910.

The first Australia Day was established in response to Australia's involvement in World War I. In 1915, the mother of four servicemen thought up the idea of a national day, with the specific aim of raising funds for wounded soldiers, and the term was coined to stir up patriotic feelings. In 1915 a committee to celebrate Australia Day was formed, and the date chosen was 30 July, on which many fund-raising efforts were run to support the war effort. It was also held in July in subsequent years of World War I: on 28 July 1916, 27 July 1917, and 26 July 1918.

The idea of a national day to be celebrated on 26 January was slow to catch on, partly because of competition with Anzac Day. Victoria adopted 26 January as Australia Day in 1931, and by 1935, all states of Australia were celebrating 26 January as Australia Day (although it was still known as Anniversary Day in New South Wales). The name "Foundation Day" persisted in local usage.

1936–1960s

The 150th anniversary of British settlement in Australia in 1938 was widely celebrated. Preparations began in 1936 with the formation of a Celebrations Council. In that year, New South Wales was the only state to abandon the traditional long weekend, and the annual Anniversary Day public holiday was held on the anniversary day – Wednesday 26 January.

The Commonwealth and state governments agreed to unify the celebrations on 26 January as "Australia Day" in 1946, although the public holiday was instead taken on the Monday closest to the anniversary.

Historian Ken Inglis wrote in 1967 that Australia Day was not publicly celebrated publicly in Canberra at that time.

1988: Bicentenary

In 1988, the celebration of 200 years since the arrival of the First Fleet was organised on a large scale as the Australian Bicentenary, with many significant events taking place in all major cities. Over 2.5 million people attended the event in Sydney. These included street parties, concerts, including performances on the steps and forecourt of the Sydney Opera House and at many other public venues, art and literary competitions, historic re-enactments, and the opening of the Powerhouse Museum at its new location. A re-enactment of the arrival of the First Fleet took place in Sydney Harbour, with ships that had sailed from Portsmouth a year earlier taking part.

Contemporary celebrations

The various celebrations and civic ceremonies such as citizenship ceremonies, the Australian of the Year awards and the Australia Day Honours (introduced in 1975) only started to be performed on Australia Day from around the 1950s onwards.

Since 1988, participation in Australia Day has increased, and in 1994 all states and territories began to celebrate a unified public holiday on 26 January – regardless of the day of the week – for the first time. Previously, some states had celebrated the public holiday on a Monday or Friday to ensure a long weekend. Research conducted in 2007 reported that 28% of Australians polled attended an organised Australia Day event and a further 26% celebrated with family and friends. This reflected the results of an earlier research project where 66% of respondents anticipated that they would actively celebrate Australia Day 2005.

Outdoor concerts, community barbecues, sports competitions, festivals and fireworks are some of the many events held in communities across Australia. These official events are presented by the National Australia Day Council, an official council or committee in each state and territory, and local committees.

In Sydney, the harbour is a focus and boat races are held, such as a ferry race and the tall ships race. In Adelaide, the key celebrations are "Australia Day in the City" which is a parade, concert and fireworks display held in Elder Park, with a new outdoor art installation in 2019 designed to acknowledge, remember and recognise Aboriginal people who have contributed to the community. Featuring the People's March and the Voyages Concert, Melbourne's events focus strongly on the celebration of multiculturalism. The Perth Skyworks is the largest single event presented each Australia Day.

Citizenship ceremonies are also commonly held, with Australia Day now the largest occasion for the acquisition of Australian citizenship. On 26 January 2011, more than 300 citizenship ceremonies took place and around 13,000 people from 143 countries took Australian citizenship. In recent years many citizenship ceremonies have included an affirmation by existing citizens. Research conducted in 2007 reported that 78.6% of respondents thought that citizenship ceremonies were an important feature of the day. In September 2019, the Morrison Government amended the Australian Citizenship Ceremonies Code to require local councils to hold a citizenship ceremony on Australia Day.

The official Australia Day Ambassador Program supports celebrations in communities across the nation by facilitating the participation of high-achieving Australians in local community celebrations. In 2011, 385 ambassadors participated in 384 local community celebrations. The Order of Australia awards are also a feature of the day. The Australia Day Achievement Medallion is awarded to citizens by local governments based on excellence in both government and non-government organisations. The governor-general and prime minister both address the nation. On the eve of Australia Day each year, the Prime Minister announces the winner of the Australian of the Year award, presented to an Australian citizen who has shown a "significant contribution to the Australian community and nation" and is an "inspirational role model for the Australian community". Subcategories of the award include Young Australian of the Year and Senior Australian of the Year, and an award for Australia's Local Hero.

Research in 2009 indicated that Australians reflect on history and future fairly equally on Australia Day. Of those polled, 43% agreed that history is the most important thing to think about on Australia Day and 41% said they look towards "our future", while 13% thought it was important to "think about the present at this time" and 3% were unsure. Despite the date reflecting the arrival of the First Fleet, contemporary celebrations are not particularly historical in their theme. There are no large-scale re-enactments and the national leader's participation is focused largely on events such as the Australian of the Year Awards announcement and Citizenship Ceremonies.

Possibly reflecting a shift in Australians' understanding of the place of Indigenous Australians in their national identity, Newspoll research in November 2009 reported that ninety percent of Australians polled believed "it was important to recognise Australia's indigenous people and culture" as part of Australia Day celebrations. A similar proportion (89%) agreed that "it is important to recognise the cultural diversity of the nation". Despite the strong attendance at Australia Day events and a positive disposition towards the recognition of Indigenous Australians, the date of the celebrations remains a source of challenge and national discussion.

Change the date movement

| It has been suggested that this article be split into multiple articles. (discuss) (January 2022) |

Some Australians regard Australia Day as a symbol of the adverse impacts of British settlement on Australia's Indigenous peoples. In 1888, prior to the first centennial anniversary of the First Fleet landing on 26 January 1788, New South Wales premier Henry Parkes was asked about inclusion of Aboriginal people in the celebrations. He replied: "And remind them that we have robbed them?"

The celebrations in 1938 were accompanied by an Aboriginal Day of Mourning. A large gathering of Aboriginal people in Sydney in 1988 led an "Invasion Day" commemoration marking the loss of Indigenous culture. Some Indigenous figures and others continue to label Australia Day as "Invasion Day", and protests occur almost every year, sometimes at Australia Day events. Thousands of people participate in protest marches in capital cities on Invasion Day/Australia Day; estimates for the 2018 protest in Melbourne range into tens of thousands.

The anniversary is also termed by some as "Survival Day" and marked by events such as the Survival Day concert, first held in Sydney in 1992, celebrating the fact that the Indigenous people and culture have survived despite colonisation and discrimination. In 2016, National Indigenous Television chose the name "Survival Day" as its preferred choice on the basis that it acknowledges the mixed nature of the day, saying that the term "recognises the invasion", but does not allow that to frame the entire story of the Aboriginal people.

In response, official celebrations have tried to include Indigenous people, holding ceremonies such as the Woggan-ma-gule ceremony, held in Sydney, which honours the past and celebrates the present.

In August 2017 the council of the City of Yarra, a local government of Melbourne, resolved unanimously that it would no longer refer to 26 January as Australia Day and would cease to hold citizenship ceremonies on that day; an event acknowledging Aboriginal culture and history was to be held instead. The City of Darebin later followed suit. The federal government immediately deprived the councils of their powers to hold citizenship ceremonies. Byron Shire Council became the third council to have its power to have citizenship ceremonies stripped.

On 13 January 2019, Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced that, with effect from Australia Day 2020, all local councils would be required to hold citizenship ceremonies on and only on 26 January and 17 September; there would also be a dress code, banning thongs and board shorts.

Crowds estimated as high as 80,000 turned out in an "Invasion Day" protest in Melbourne alone in 2019, and rallies were held across the country.

On 12 November 2019, following an online survey, the Inner West Council became the first local authority in Sydney to end Australia Day celebrations, encouraging residents instead to attend the Aboriginal Yabun festival held on that day. The council still holds citizenship ceremonies on Australia Day.

On 23 February 2021, the City of Mitcham became the first local Council in SA to vote to officially oppose the date of Australia Day. Mayor Dr Holmes-Ross said she felt “comfortable with the council holding events on Australia Day, but I don’t feel comfortable with the date of Australia Day”.

Suggested changes to the date

Both before the establishment of Australia Day as the national day of Australia, and in the years after its creation, several dates have been proposed for its celebration and, at various times, the possibility of moving Australia Day to an alternative date has been mooted. Some reasons put forward are that the current date, celebrating the foundation of the Colony of New South Wales, lacks national significance; that the day falls during school holidays which limits the engagement of schoolchildren in the event; and that it fails to encompass members of the Indigenous community and some others who perceive the day as commemorating the date of an invasion of their land. Connected to this is the suggestion that moving the date would be seen as a significant symbolic act.

Amongst those calling for change have been Tony Beddison, then chairman of the Australia Day Committee (Victoria), who argued for change and requested debate on the issue in 1999; and Mick Dodson, Australian of the Year in 2009, who called for debate as to when Australia Day was held.

Such a move would have to be made by a combination of the Australian Federal and State Governments, and has lacked sufficient political and public support. In 2001 Prime Minister John Howard stated that he acknowledged Aboriginal concerns with the date, but that it was nevertheless a significant day in Australia's history, and thus he was in favour of retaining the current date. He also noted that 1 January, which was being discussed in light of the Centenary of Federation, was inappropriate as it coincided with New Year's Day. In 2009 Prime Minister Kevin Rudd gave a "straightforward no" to a change of date, speaking in response to Mick Dodson's suggestion to reopen the debate. The Opposition Leader, Malcolm Turnbull, echoed Rudd's support of 26 January, but, along with Rudd, supported the right of Australians to raise the issue. At the State level, New South Wales Premier Nathan Rees stated that he was yet to hear a "compelling argument" to support change; and Queensland Premier Anna Bligh expressed her opposition to a change.

In June 2017 the annual National General Assembly of the Australian Local Government Association voted (by a majority of 64–62) for councils to consider how to lobby the federal government for a date change.

Polling

2000s

In 2004, a Newspoll poll that asked if the date of Australia Day should be moved to one that is not associated with European settlement found 79% of respondents favoured no change, 15% favoured change, and 6% were uncommitted. Historian Geoffrey Blainey said in 2012 that he believed 26 January worked well as Australia Day and that it was at that time more successful than it had ever been.

2010s

A January 2017 poll conducted by McNair yellowSquares for The Guardian found that 68% of Australians felt positive about Australia Day, 19% were indifferent and 7% had mixed feelings, with 6% feeling negative about Australia Day. Among Indigenous Australians, however, only 23% felt positive about Australia Day, 31% were negative and 30% had mixed feelings, with 54% favouring a change of date. A September 2017 poll conducted by Essential Polling for The Guardian found that 54% were opposed to changing the date; 26% of Australians supported changing the date and 19% had no opinion.

A poll conducted by progressive public policy think tank The Australia Institute in 2018 found that 56% do not mind what day it is held. The same poll found that 49% believe that the date should not be on a date that is offensive to Indigenous Australians, but only 37% believed the current date was offensive.

Prior to Australia Day 2019, the conservative public policy think tank Institute of Public Affairs (IPA) published the results of a poll in which 75% of Australians wanted the date to stay, while the new nationalist Advance Australia Party's poll had support at 71%. Both groups asked questions about pride in being Australian prior to the headline question.

The Social Research Centre, a subsidiary of the Australian National University, also released a report in January 2019. Their survey found that, when respondents know that 26 January is the anniversary of the arrival of the First Fleet at Port Jackson, 70% believe it is the best date for Australia Day, and 27% believe it is not. The report includes demographic factors which affect people's response, such as age, level of education, and state or territory of residence. Those who did not support 26 January as the best date then indicated their support for an alternate date. The three most supported dates were 27 May, 1 January and 8 May.

2020s

Polling by Essential Media since 2015 suggests that the number of people celebrating Australia Day is declining, indicating a shift in attitudes. In 2019, 40% celebrated the day; in 2020, 34%, and in 2021 it was down to 29% of over 1000 people surveyed. In 2021, 53% said that they are treating the day as just a public holiday.

A poll commissioned by the IPA in December 2020 and published in January 2021 showed that support for changing the date had remained a minority position. In January 2021, an Essential poll reported that 53% supported a separate day to recognise Indigenous Australians; however only 18% of these thought that it should replace Australia Day. A poll by Ipsos for The Age / The Sydney Morning Herald reported in January 2021 that 28% were in support of changing the date, 24% were neutral and 48% did not support changing the date. 49% believed that the date would change within the next decade and 41% believed that selecting a new date would improve the lives of Indigenous Australians. Results were split by demographic factors, with age being a significant factor. 47% of people aged 18–24 supported changing the date, compared to only 19% among those aged 55 years or older. Individuals who voted for the Greens were most likely to support the date change at 67%, followed by Labor voters at 31% and Coalition voters at 23%.

Suggested alternative dates

- Federation of Australia (1 January)

- As early as 1957, 1 January was suggested as a possible alternative day, to commemorate the Federation of Australia. In 1902, the year after Federation, 1 January was named "Commonwealth Day". However, New Year's Day was already a public holiday, and Commonwealth Day did not gather much support.

- Federation of Australia 1901 alternative date (19 January)

- Proposed as an alternative because it is only one week earlier than Australia Day and can represent the year of Federation.

- Independence day (3 March)

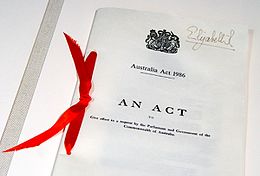

- There has been support for an independence day, 3 March, to represent the enacting of the Australia Act 1986.

- Anzac Day (25 April)

- There has been a degree of support by some in recent years for making Anzac Day, 25 April, Australia's national day, including in 1999, by Anglican Archbishop of Brisbane Peter Hollingworth. In 2001, following comments made during a review into the future of Anzac Day, the idea of a merger was strongly opposed by Prime Minister John Howard and Opposition Leader Kim Beazley, who clarified his earlier position.

- Mate (8 May)

- Starting 2017, there has been a partly serious suggestion to move Australia day to 8 May. This is primarily because of the homophonous quality between "May 8" and the Australian idiom "mate", but also because the opening of the first Federal Parliament was on 9 May.

- Opening of the first Federal Parliament (9 May)

- The date 9 May is also sometimes suggested, the date on which the first Federal Parliament was opened in Melbourne in 1901, the date of the opening of the Provisional Parliament House in Canberra in 1927, and the date of the opening of the New Parliament House in 1988. The date has, at various times, found support from former Queensland Premier Peter Beattie, Tony Beddison, and Geoffrey Blainey. However, the date has been seen by some as being too closely connected with Victoria, and its location close to the start of winter has been described as an impediment.

- Anniversary of the 1967 referendum (27 May)

- The anniversary of the 1967 referendum to amend the federal constitution has also been suggested. The amendments enabled the federal parliament to legislate with regard to Indigenous Australians and allowed for Indigenous Australians to be included in the national census. The public vote in favour was 91%.

- Acceptance of the Constitution (9 July)

- This is the date when Queen Victoria accepted the Constitution of Australia.

- Wattle Day (1 September)

- Wattle Day is the first day of spring in the southern hemisphere. Australia's green and gold comes from the wattle, and it has symbolised Australia since the early 1800s. Wattle Day has been proposed as the new date for Australia Day since the 1990s and is supported by the National Wattle Day Association.

- Tenterfield Oration (24 October)

- "A more meaningful day is October 24, when in 1889 Sir Henry Parkes, the "Father of Federation", gave his pivotal speech at Tenterfield in NSW, which set the course for federation."

- Eureka Stockade (3 December)

- The Eureka Stockade on 3 December has had a long history as an alternative choice for Australia Day, having been proposed by The Bulletin in the 1880s. The Eureka uprising occurred in 1854 during the Victorian gold rush, and saw a failed rebellion by the miners against the Victorian colonial government. Although the rebellion was crushed, it led to significant reforms, and has been described as being the birthplace of Australian democracy. Supporters of the date have included senator Don Chipp and former Victorian Premier Steve Bracks. However, the idea has been opposed by both hard-left unions and right-wing nationalist groups, both of whom claim symbolic attachment to the event, and by some who see it as an essentially Victorian event.

See also

References

- "What does Australia Day mean?". Archived from the original on 28 May 2016.

- ^ Darian-Smith, Kate. "Australia Day, Invasion Day, Survival Day: a long history of celebration and contestation". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- "Australia Day – A History". Victoria State Government. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- "History". Australia Day. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ Hirst, John (26 January 2008). "Australia Day in question". The Age. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- National Australia Day Council Annual Report 2010–11 p. 3

- ^ Tippet, Gary (25 January 2009). "90 years apart and bonded by a nation". Melbourne: Australia Day Council of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- Marlow, Karina (21 January 2016). "Australia Day, Invasion Day, Survival Day: What's in a name?". NITV. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Gabrielle Chan (26 January 2017). "Most Indigenous Australians want date and name of Australia Day changed, poll finds". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- Flynn, Eugenia (23 January 2018). "Abolish Australia Day – changing the date only seeks to further entrench Australian nationalism". IndigenousX. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Knaus, Christopher; Wahlquist, Calla (26 January 2018). "'Abolish Australia Day': Invasion Day marches draw tens of thousands of protesters". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ "Ipsos Australia Day Poll Report". Ipsos. 24 January 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ "Poll - Mainstream Australians Continue To Support Australia Day On 26 January". Institute of Public Affairs. 17 January 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ "Australia Day Poll" (PDF). January 2021.

This poll of 1,038 Australians was commissioned by the Institute of Public Affairs. Data for this poll was collected by marketing research firm Dynata between 11-13 December 2020.

- ^ Topsfield, Jewel (24 January 2021). "Not going to solve anything: Why some Australians don't want a date change". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- Ekirch, A. Robert (December 1984). "Great Britain's Secret Convict Trade to America, 1783–1784". The American Historical Review. 89 (5): 1291. doi:10.2307/1867044. JSTOR 1867044.

- David Hill, 1788: The Brutal Truth of the First Fleet, pp. 147–150

- Phillip, Arthur (1789). The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay with an Account of the Establishment of the Colonies of Port Jackson and Norfolk Island; compiled from Authentic Papers, which have been obtained from the several Departments to which are added the Journals of Lieuts. Shortland, Watts, Ball and Capt. Marshall with an Account of their New Discoveries, embellished with fifty five Copper Plates, the Maps and Charts taken from Actual Surveys, and the plans and views drawn on the spot, by Capt. Hunter, Lieuts. Shortland, Watts, Dawes, Bradley, Capt. Marshall, etc. London.

- "NSW Land and Property Management Authority, A Guide to Searching New South Wales Land Title Records" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- Hobson, Nick. "Australia Day". Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- "New South Wales 1867–1870".

- Bonyhady, Tim (2003). The Colonial Earth. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Publishing. p. 42. ISBN 0-522-85053-7.

- ^ Kwan, Elizabeth. "Celebrating Australia: A History of Australia Day essay". Australia Day. National Australia Day Council. Archived from the original on 4 January 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- Clark, Manning in "Student Resources: Australia Day History". Australia Day. Australia Day Council of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 4 January 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- "Sydney". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. 1 February 1817. pp. 2–3. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ "Student Resources: Australia Day History". Australia Day. Australia Day Council of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 4 January 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- Watts, John (24 January 1818). "Government and General Orders". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. p. 1. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ "The Regatta". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. 28 January 1837. p. 2. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- "Regatta". Sydney Herald. 30 January 1837. p. 2. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ "Dinner of the United Australians". Sydney Herald. 30 January 1837. p. 2. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ "The Jubilee". Sydney Herald. 29 January 1938. p. 2. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- "The Regatta". The True Colonist Van Diemen's Land Political Despatch, And Agricultural And Commercial... No. 800. Tasmania, Australia. 7 December 1838. p. 4. Retrieved 7 December 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

-

This Misplaced Pages article incorporates CC BY 4.0 licensed text from: "January twenty-six". John Oxley Library Blog. State Library of Queensland. 22 January 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

This Misplaced Pages article incorporates CC BY 4.0 licensed text from: "January twenty-six". John Oxley Library Blog. State Library of Queensland. 22 January 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Marsh, Walter (24 January 2019). "First Fleet or summer holiday: Why does South Australia celebrate January 26?". Adelaide Review. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- Brown, Bill (27 July 2015). "The first Australia Day: 30 July 1915". ABC South East NSW. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- "Australia Day fixed for July 30. Meeting committee appointed". The Sydney Morning Herald. 7 June 1915. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ "For Australia's Heroes – the other 'Australia Day', 30 July 1915". The Australian War Memorial. Canberra. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- Adelaide Advertiser, 25 July 1917, Trove

- Adelaide Advertiser, 27 July 1918, Trove

- ^ Bongiorno, Frank (21 January 2018). "Why Australia Day survives, despite revealing a nation's rifts and wounds". The Conversation. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- "Australia's National Day". The Central Queensland Herald. Rockhampton, Qld. 3 February 1955. p. 3. Retrieved 23 September 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Chronology". Australia Day Council of NSW. Archived from the original on 13 June 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- "History of Australia Day". National Australia Day Council. Retrieved 27 January 2007.

- "It's an Honour". Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (Australia). Australian Government. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- "Australia Day History". Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- Kwan, Elizabeth (2007). "Celebrating Australia: A History of Australia Day" (PDF). National Australia Day Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ Deery, Margaret; Jago, Leo Kenneth; Fredline, Liz (2007). "Celebrating a National Day: the Meaning and Impact of Australia Day Events". 4th International Event Research Conference. Victoria University. ISBN 978-0-9750957-9-9.

- Elliott and Shanahan Research (2004). Newspoll Omnibus Survey Australia Day 2005

- "National Australia Day Council: Annual Report 2008–2009" (PDF). National Australia Day Council. 2009. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- "Australia Day". Australia Day Council of South Australia. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- Herald Sun, "Australia Day Program", 20 January 2010.

- Pearson, W. And O'Neill, G. (2009) 'Australia Day: A Day for All Australians?' in McCrone, D. and McPherson, G. (eds). National Days: Constructing and Mobilising National Identity, Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire, p. 79

- "City of Perth Australia Day Skyworks". ABC Perth Events. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- Department of Immigration and Citizenship (2011) Annual Report 2010–2011, p. 247

- "Record number of Australian citizens to be conferred this Australia Day". The Hon David Coleman MP. 26 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- National Australia Day Council Annual Report 2010–11 p. 7

- "Selection criteria". National Australia Day Council. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 29 October 2007.

- Newspoll research conducted in November 2009 for the National Australia Day Council

- National Australia Day Council, Annual Report 2008–2009, p. 8

- Newspoll Omnibus Survey.pdf

- Narushima, Yuko (23 January 2010). "Obey the law at least, Abbott tells migrants". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- Wahlquist, Calla (19 January 2018). "What our leaders say about Australia Day – and where did it start, anyway?". Guardian Australia. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- "Reconciliation can start on Australia Day". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. 29 January 2007. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- "Invasion Day marked by thousands of protesters calling for equal rights, change of date". ABC News. 27 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- "Australia Day 2018: Thousands turn out for protest in Melbourne CBD". Herald Sun. 26 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Knaus, Christopher; Wahlquist, Calla (26 January 2018). "'Abolish Australia Day': Invasion Day marches draw tens of thousands of protesters". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- "Invasion Day rally 2019: where to find marches and protests across Australia". The Guardian. 25 January 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- "Significant Aboriginal Events in Sydney". Sydney City Council website. Archived from the original on 4 February 2007. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- "Australia Day, Invasion Day, Survival Day: What's in a name?".

- "Young and free gather to rejoice – National". www.smh.com.au. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Melbourne's Yarra council votes unanimously to move Australia Day citizenship ceremonies". Sydney Morning Herald. 16 August 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- Cowie, Tom (16 August 2017). "Yarra council stripped of citizenship power after cancelling Australia Day celebrations". The Age. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- Wahlquist, Calla (16 August 2017). "Yarra council stripped of citizenship ceremony powers after Australia Day changes". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- Daley, Paul (16 August 2017). "Turnbull is wrong – Australia Day and its history aren't 'complex' for Indigenous people". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "Darebin council stripped of citizenship ceremony after controversial Australia Day vote". ABC News. 22 August 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Wahlquist, Calla (24 September 2018). "Scott Morrison calls for new national day to recognise Indigenous people". Guardian Australia. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- Zhou, Naaman (13 January 2019). "Scott Morrison to force councils to hold citizenship ceremonies on Australia Day". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- Truu, Maani (26 January 2019). "Tens of thousands attend 'Invasion Day' rallies across Australia". SBS News. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- McNab, Heather (13 November 2019). "'The right thing to do': Sydney council drops Australia Day celebrations". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- "'Mitcham Council backs mayor's push to join 'change the date of Australia Day' movement". The Advertiser. 3 March 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ Ballantine, Derek (5 December 1999). "Australia Day 'should be changed'". Sunday Tasmanian. Hobart. p. 6.

- ^ Nicholson, Rod (25 January 2009). "Ron Barassi wants an Australia Day we can all enjoy". Herald Sun. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 3 July 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- "Dodson wants debate on Australia Day date change". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 26 January 2009. Archived from the original on 14 December 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- ^ Day, Mark (9 December 1999). "Time for a birthday with real meaning". Daily Telegraph. Sydney. p. 11.

- Rodda, Rachel (27 January 2001). "Nation's birthday debate rekindled". Daily Telegraph. Sydney. p. 7.

- "Rudd says 'no' to Australia Day date change". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 26 January 2009. Archived from the original on 13 December 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- "Local councils across country push for Australia Day date change". The Guardian. 21 June 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- "Newspoll" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- "?". Herald Sun. Archived from the original on 30 December 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- Murphy, Katherine (5 September 2017). "Most voters want Australia Day to stay on 26 January – Guardian Essential poll". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ Taylor, Josh. "Should Australia #ChangeTheDate? Polls Vary Depending On What Is Asked". BuzzFeed. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- Borys, Stephanie (18 January 2018). "Australia Day: Most Australians don't mind what date it's held, according to new poll". ABC. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- "Australia Day poll: While many believe date shouldn't offend, many ignore significance of Jan 26". NITV. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ "Barbeques and black armbands | Social Research Centre". www.srcentre.com.au. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- Foster, Ally (20 January 2021). "Australia Day poll shows how attitudes to changing the date have shifted". NewsComAu. Nationwide News Pty Limited. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- Topsfield, Jewel (24 January 2021). "Almost half oppose campaign to change Australia Day: poll". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- "*Ø* Wilson's Almanac free daily ezine". Wilson's Almanac. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- ^ Hirst, John (26 January 2008). "Australia Day in question". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- Macfarlane, Ian (26 January 2017). "Australia Day: let's shift it for a truly national celebration". The Australian. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- "We only became independent of Britain on this day in 1986". The Australian. 3 March 2011.

- Ballantyne, Derek (5 December 2009). "DUMP IT! – Australia Day boss says date divides the nation". The Sunday Mail. Brisbane. p. 1.

- Stewart, Cameron (14 April 2001). "Anzac rethink enrages diggers". Weekend Australian. Sydney. p. 1.

- "Anzac Day merger idea gets shot down". Hobart Mercury. Hobart. 26 April 2001. p. 1.

- "Change the date: When should Australia Day be held?". News.com.au. 26 January 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- Williams, Emma (12 January 2017). "Comedian has most Aussie solution for controversial Australia Day date". The Courier-Mail. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- "May8 – The New Australia Day Mate!". Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ "Day for all Australians". The Sydney Morning Herald. 26 January 2002.

- Hudson, Fiona (10 May 2001). "Call to shift Australia Day". Hobart Mercury.

- ^ Turner, Jeff (26 January 2000). "Divided on our national day". The Advertiser. Adelaide. p. 19.

- Robin, Libby (2007). How a Continent Created a Nation. University of New South Wales Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-86840-891-0.

- Searle, Suzette. "Australia Day – our day needs a new date" (PDF). wattleday.asn.au. Wattle Association Inc. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Williams, Warwick. "October 24 significant". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018.

- Hirst, John (26 January 2008). "Australia Day in question". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- ^ Macgregor, Duncan; Leigh, Andrew; Madden, David; Tynan, Peter (29 November 2004). "Time to reclaim this legend as our driving force". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 15.

- "Our day 'parochial'". Daily Telegraph. Sydney. 6 December 1999. p. 15.