This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Janizary (talk | contribs) at 20:45, 16 February 2007. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:45, 16 February 2007 by Janizary (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can submit an edit request, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

Siddhārtha Gautama (Sanskrit सिद्धार्थ गौतम, Pali Gotama Buddha) was a spiritual teacher from ancient India and the historical founder of Buddhism. He is universally recognized by Buddhists as the Supreme Buddha of our age. The time of his birth and death are uncertain; most modern historians date his lifetime from 563 BCE to 483 BCE, though some have suggested a date about a century later than this..

Gautama, also known as Sakyamuni or Shakyamuni (“sage of the Shakyas”), is the key figure in Buddhism, and accounts of his life, discourses, and monastic rules were summarized after his death and memorized by the saṅgha. Passed down by oral tradition, the Tripiṭaka, the collection of discourses attributed to Gautama, was committed to writing about 400 years later.

Buddha's life

As few of the details of the Buddha's life can be independently verified, it is difficult to gauge the historical accuracy of these accounts. The main sources of information on Siddhārtha Gautama's life are the earliest available Buddhist texts. The following is a summary of those narratives.

Conception and birth

According to tradition, Siddhārtha was born more than 200 years before the reign of the Maurya king Aśoka (273–232 BCE).

Siddhartha was born in Lumbini in modern day Nepal. His father was Suddhodana, the chief of the Shakya nation, one of several ancient tribes in the growing state of Kosala; Gautama was the family name. His mother was Queen Maya (Māyādevī), King Sudhodhana's wife, who was a Koliyan princess. On the night Siddhartha was conceived, Queen Maya dreamt that a white elephant entered her right side, and ten lunar months later Siddhartha was born from her right side (see image right). As was the Shakya tradition, when his mother Queen Maya fell pregnant, she returned to her father's kingdom to give birth, but after leaving Kapilavastu (which can be located in north part of Siddharthnagar district of Uttar Pradesh in India), she gave birth along the way at Lumbini in a garden beneath a sal tree.

The day of the Buddha's birth is widely celebrated in Buddhist countries as Vesak. Various sources hold that the Buddha's mother died at his birth, a few days or seven days later. The infant was given the name Siddhartha (Pāli: Siddhatta), meaning “he who achieves his aim”. During the birth celebrations, the hermit seer Asita journeyed from his mountain abode and announced that this baby would either become a great king (chakravartin) or a great holy man. This occurred after Siddhartha placed his feet in Asita's hair and Asita examined the birthmarks. Suddhodarna held a naming ceremony on the fifth day, and invited eight brahmin scholars to read the future. All gave a dual prediction that the baby would either become a great king or a great holy man. Kondanna, the youngest, and later to be the first arahant, was the only one who unequivocally predicted that Siddhartha would become a Buddha.

While later tradition and legend characterized Śuddhodana as a hereditary monarch, the descendant of the Solar Dynasty of Ikṣvāku (Pāli: Okkāka), many scholars believe that Śuddhodana was the elected chief of a tribal confederacy.

Early life and Marriage

Siddhartha, destined to a luxurious life as a prince, had three palaces (one for each season) especially built for him. His father, King Śuddhodana, wishing for Siddhartha to be a great king, shielded his son from religious teachings or knowledge of human suffering. Siddhartha was brought up by his mother's younger sister, Maha Pajapati.

As the boy reached the age of 16, his father arranged his marriage to Yaśodharā (Pāli: Yasodharā), a cousin of the same age. In time, she gave birth to a son, Rahula. Siddhartha spent 29 years as a Prince in Kapilavastu, a place now situated in Nepal. Although his father ensured that Siddhartha was provided with everything he could want or need, Siddhartha felt that material wealth was not the ultimate goal of life.

The Great Departure

At the age of 29, however, the young prince left his palace for a short excursion. While venturing outside of his palace, and despite his father's effort to remove the sick, aged and suffering, Siddhartha was said to have seen an old man. Disturbed by this, and the fact that all people would eventually grow old, the prince went on further trips where he encountered, variously, a crippled man, a diseased man, a decaying corpse, and an ascetic. Deeply depressed by these sights, he sought to overcome old age, illness, and death by living the life of an ascetic. Siddhartha soon left his palace, his possessions, and his entire family at age 29, to take up the lonely life of a wandering monk.

Abandoning his inheritance, he is then said to have dedicated his life to learning how to overcome suffering. He meditated with two hermits, and, although he achieved high levels of meditative consciousness, he was still not satisfied with his path.

Siddhartha then chose the robes of a mendicant monk and headed to Magadha in what is today Bihar in India. He began his training in the ascetic life and practicing vigorous techniques of physical and mental austerity. Gautama proved quite adept at these practices, and surpassed even his teachers.

However, he found no answer to his questions regarding freedom from sufferings. Leaving behind his caring teachers, he and a small group of close companions set out to take their austerities even further. Gautama tried to find enlightenment through near total deprivation of worldly goods, including food, practicing self-mortification. After nearly starving himself to death by restricting his food intake to around a leaf or nut per day (some sources claim that he nearly drowned), Gautama began to reconsider his path. Then, he remembered a moment in childhood in which he had been watching his father start the season's plowing, and he had fallen into a naturally concentrated and focused state that was blissful and refreshing.

The Great Enlightenment

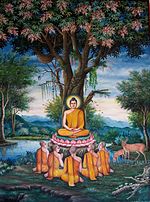

After asceticism and concentrating on meditation or Anapana-sati (awareness of breathing in and out), Gautama is said to have discovered what Buddhists call the Middle Way—a path of moderation away from the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification. He accepted a little milk rice pudding from a village girl named Sujata. Then, sitting under a pipal tree, now known as the Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya, he vowed never to arise until he had found the Truth. Kaundinya and the other five companions, believing that he had abandoned his search and become indisciplined, left. At the age of 35, he attained Enlightenment; according to some traditions, this occurred approximately in May, and according to others in December. Gautama, from then on, was known as the Buddha or "Awakened One". Oftentimes, he is referred to in Buddhism as Shakyamuni Buddha or "The Awakened One of the Shakya Clan."

At this point, he is believed to have stated that he had realized complete awakening and insight into the nature and cause of human suffering which was ignorance, along with steps necessary to eliminate it. These truths were then categorized into the Four Noble Truths; the state of supreme liberation—possible for any being—was called Nirvana. He then came to possess the Nine Characteristics, which are said to belong to every Buddha.

According to one of the stories in the Āyācana Sutta (Samyutta Nikaya VI.1), a scripture found in the Pāli and other canons, immediately after his Enlightenment, the Buddha was wondering whether or not he should teach the Dharma to human beings. He was concerned that, as human beings were overpowered by greed, hatred and delusion, they would not be able to see the true dharma, which was subtle, deep and hard to understand. However, a divine spirit, Brahmā Sahampati, interceded and asked that he teach the dharma to the world, as "there will be those who will understand the Dharma". With his great compassion to all beings in the universe, the Buddha agreed to become a teacher.

At the Deer Park near Vārāṇasī (Benares) in northern India, he set in motion the Wheel of Dharma by delivering his first sermon to the group of five companions with whom he had previously sought enlightenment. They, together with the Buddha, formed the first saṅgha, the company of Buddhist monks, and hence, the first formation of Triple Gem (Buddha, Dharma and Sangha) was completed, with Kaundinya becoming the first arahant.

According to tradition, the Buddha emphasized ethics and correct understanding. He questioned the average person's notions of divinity and salvation. He stated that there is no intermediary between mankind and the divine; distant gods are subjected to karma themselves in decaying heavens; and the Buddha is solely a guide and teacher for the sentient beings who must tread the path of Nirvāṇa (Pāli: Nibbāna) themselves to attain the spiritual awakening called bodhi and see truth and reality as it is. The Buddhist system of insight, thought, and meditation practice is not believed to have been revealed divinely, but by the understanding of the true nature of the mind, which could be discovered by anybody.

For the remaining 45 years of his life, the Buddha is said to have traveled in the Gangetic Plain of Northeastern India and Southern Nepal, teaching his doctrine and discipline to an extremely diverse range of people— from nobles to outcaste street sweepers, including many adherents of rival philosophies and religions. The Buddha founded the community of Buddhist monks and nuns (the Sangha) to continue the dispensation after his Parinirvāna (Pāli: Parinibbāna) or "complete Nirvāna", and made thousands of converts. His religion was open to all races and classes and had no caste structure. On the other hand, Buddhist texts record that he was reluctant to ordain women as nuns: he eventually accepted them on the grounds that their capacity for enlightenment was equal to that of men (and the Lotus Sutra, in Chapter 12, contains a description of the dragon king's daughter attaining enlightenment in her present body), but he gave them certain additional rules (Vinaya) to follow.

The Great Passing

According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta of the Pali canon, at the age of 80, the Buddha announced that he would soon enter Parinirvana or the final deathless state abandoning the earthly body. After this, the Buddha ate his last meal, which, according to different translations, was either a mushroom delicacy or soft pork, which he had received as an offering from a blacksmith named Cunda. Falling violently ill, Buddha instructed his attendant Ānanda to convince Cunda that the meal eaten at his place had nothing to do with his passing and that his meal would be a source of the greatest merit as it provided the much-needed energy for the Buddha.

Ananda protested Buddha's decision to enter Parinirvana in the abandoned jungles of Kuśināra (Pāli: Kusināra) of the Mallas. Buddha, however, reminded Ananda how Kushinara was a land once ruled by a righteous king that resounded with joy:

44. Kusavati, Ananda, resounded unceasingly day and night with ten sounds -- the trumpeting of elephants, the neighing of horses, the rattling of chariots, the beating of drums and tabours, music and song, cheers, the clapping of hands, and cries of "Eat, drink, and be merry!"

Buddha then asked all the attendant Bhikshus to clarify any doubts or questions they had. They had none. He then finally entered Parinirvana. The Buddha's final words were, "All composite things pass away. Strive for your own salvation with diligence." The Buddha's body was cremated and the relics were placed in monuments or stupas, some of which are believed to have survived until the present. For example, The Temple of the Tooth or "Dalada Maligawa" in Sri Lanka is the place where the right tooth relic of Buddha is kept at present.

According to the Pāli historical chronicles of Sri Lanka, the Dīpavaṃsa and Mahāvaṃsa, the coronation of Aśoka (Pāli: Asoka) is 218 years after the death of Buddha. According to one Mahayana record in Chinese (十八部論 and 部執異論), the coronation of Aśoka is 116 years after the death of Buddha. Therefore, the time of Buddha's passing is either 486 BCE according to Theravāda record or 383 BCE according to Mahayana record. However, the actual date traditionally accepted as the date of the Buddha's death in Theravāda countries is 544 or 543 BCE, because the reign of Aśoka was traditionally reckoned to be about 60 years earlier than current estimates (based on Aśoka's own inscriptions, and therefore among the soundest dates in early Indian history).

Physical characteristics

Main article: Physical characteristics of the BuddhaBuddha is perhaps one of the few sages for whom we have mention of his rather impressive physical characteristics. He was at least six feet tall and had a strong enough body to be noticed by one of the kings and was asked to join his army as a general. He is also believed by Buddhists to have "the 32 Signs of the Great Man".

Although the Buddha was not represented in human form until around the 1st century CE (see Buddhist art), his physical characteristics are described in one of the central texts of the traditional Pali canon, the Digha Nikaya. They help define the global aspect of the historical Buddha, his physical appearance is described by Prince Siddhartha's wife to his son Rahula upon Buddha's return in the scripture of the "Lion of Men".

Based on descriptions of him having been a Kshatriya, he was probably of Indo-Aryan ethnic heritage and had the physical characteristics most common to the Aryan warrior castes of south-central Asia, typically found among the Vedic Aryans, Scythians and Persians.

Teachings

Main article: Buddhist philosophyWhile there is disagreement amongst various Buddhist sects over more esoteric aspects of Buddha's teachings and over disciplinary rules for monks, there is generally agreement over these points:

- The Four Noble Truths: that suffering is an inherent part of existence; that the origin of suffering is ignorance and the main symptoms of that ignorance are attachment and craving; that attachment and craving can be ceased; and that following the Noble Eightfold Path will lead to the cessation of attachment and craving and therefore suffering.

- The Noble Eightfold Path: right understanding, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration.

- The concept of dependent origination: that any phenomenon 'exists' only because of the ‘existence’ of other phenomena in a complex web of cause and effect covering time past, present and future. Because all things are thus conditioned and transient (anicca), they have no real independent identity (anatta).

- Rejection of the infallibility of accepted scripture: Teachings should not be accepted unless they are borne out by our experience and are praised by the wise. See the Kalama Sutta for details.

- Anicca (Sanskrit: anitya): That all things are impermanent.

- Anatta (Sanskrit: anātman): That the perception of a constant "self" is an illusion.

- Dukkha (Sanskrit: duḥkha): That all beings suffer from all situations due to unclear mind.

Language

It is unknown what language the Buddha spoke, and no conclusive documentation has been made at this point. However, modern scholars, primarily philologists, believe it is most likely that the Buddha spoke an East-Indian popular language, Mâgadhî Prakrit.

Buddha as viewed by other religions

Hinduism

Buddhism is a dharmic religion. The systems of Buddhism and Hinduism, some say, must not be considered to be either contradictory to one another or completely self contained. Coomaraswamy wrote:

- "The more superficially one studies Buddhism, the more it seems to differ from Brahmanism in which it originated; the more profound our study, the more difficult it becomes to distinguish Buddhism from Brahmanism, or to say in what respects, if any, Buddhism is really unorthodox."

Buddhist scholar Rahula Vipola wrote that the Buddha was trying to shed the true meaning of the Vedas. Buddha is said to be a knower of the Veda (vedajña) or of the Vedanta (vedântajña) (Sa.myutta, i. 168) and (Sutta Nipâta, 463).

Hinduism and Buddhism share many common features including Sanskrit, yoga, karma and dharma.

Taoism, Confucianism and Shintoism

Main article: Buddhism and Eastern teachingThe arrival of Buddhism caused Taoism to renew and restructure itself and address existential questions raised by Buddhism. Buddhism was seen as a kind of foreign Taoism and its scriptures were translated into Chinese with Taoist vocabulary. Chan (Seon, Thien, or Zen) Buddhism in particular holds many beliefs in common with philosophical Taoism. Some early Chinese Taoist-Buddhists thought Buddha to be a reincarnation of Lao Tzu born in the land of barbarians.

Buddhism shares many commonalities with Neo-Confucianism , which is Confucianism with more religious elements. In fact, the ritual of ancestor worship normally practiced by Confucianists, has been adapted to Chinese Buddhist beliefs.

In the Japanese religion of Shinto, the long coexistence of Buddhism and Shintoism resulted in the merging of Shintoism and Buddhism. Gods in Shintoism were given a position similar to the Hindu gods in Buddhism. Moreover, because one of Mahayana Buddha's (Dainichi Nyorai) symbols was the sun, many equated Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess, as the previous reincarnation (bodhisattva) of Dainichi Nyorai. However, the Tokugawa Shogunate era saw a revival movement within Shinto. Some Shinto scholars started to argue that Buddhas were previous incarnations of Shinto gods, thus turning the position of Shintoism and Buddhism upside down. Shinto and Buddhism were officially separated after the Meiji Restoration.

Islam

If you desire to see the most noble of mankind, look at the king in beggar's clothing; it is he whose sanctity is great among men.

— Abdul Atahiya, Arab Poet.

The Buddhist monastic class flowed into what came to be called Islamic monasticism — Sufism — which has given many poets and scientists to both Islam and the world. The Qalandariyah Sufi Order, a Muslim mystical movement, attracted many Buddhist monks. This order arose in 9th century as a result of the Malamatiyya, and became established in Khorasan (Eastern Persia) as early in the 11th century.

Ascetic practices within the Sufi philosophy are associated with Buddhism. The notion of purification (cleaning one' s soul from all evil things and trying to reach Nirvana and to become immortal in Nirvana) plays an important role in Buddhism. The same idea shows itself in the belief of vuslat (communion with God) in Sufi philosophy.

The mission of the Buddha was quite unique in its character, and therefore it stands quite apart from the many other religions of the world. His mission was to bring the birds of idealism flying in the air nearer to the earth, because the food for their bodies belonged to the earth.

— Hazrat Inayat Khan.

The Indian scholar Maulana Abul Kalam Azad proposed in a commentary on the Qur'an that Siddhartha Gautama is the prophet of Islam Dhū'l-Kifl referred to in Sura 21 and Sura 38 of the Qur'an together with the Biblical characters Ishmael, Idris (Enoch), and Elisha. Azad suggested that the Kifl in Dhū'l-Kifl (Ar: "possessor of a double portion") is an Arabic pronunciation of Kapilavastu, where the Buddha spent his early life. Azad did not, however, provide direct historical evidence to support his speculation. According to other ancient Muslim scholars Dhū'l-Kifl was either a righteous man and not a prophet, or he was the prophet called Ezekiel in the Bible.

In Afghanistan, the Islamic theocratic Taliban government persecuted Buddhists and destroyed a number of ancient Buddhist relics.

Christianity and Judaism

The Greek legend of "Barlaam and Ioasaph", sometimes mistakenly attributed to the 7th century John of Damascus but actually written by the Georgian monk Euthymios in the 11th century, was ultimately derived, through a variety of intermediate versions (Arabic and Georgian) from the life story of the Buddha. The king-turned-monk Ioasaph (Georgian Iodasaph, Arabic Yūdhasaf or Būdhasaf) ultimately derives his name from the Sanskrit Bodhisattva, the name used in Buddhist accounts for Gautama before he became a Buddha. Barlaam and Ioasaph were placed in the Greek Orthodox calendar of saints on 26 August, and in the West they were entered as "Barlaam and Josaphat" in the Roman Martyrology on the date of 27 November.

The story was translated into Hebrew in the Middle Ages as "Ben-Hamelekh Vehanazir" ("The Prince and the Nazirite"), and is widely read by Jews to this day.

See also

- Iconography of the Buddha

- Buddha as an Avatar of Vishnu

- Buddha

- List of the 28 Buddhas

- Maitreya Buddha (Future Buddha)

- Physical characteristics of the Buddha

Notes

- The Dating of the Historical Buddha: A Review Article

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2006. Lumbini, the birthplace of the Lord Buddha. Available from: http://whc.unesco.org/pg.cfm?cid=31&id_site=666. Accessed 17 November 2006.

- Turpie, D. 2001. Wesak And The Re-Creation of Buddhist Tradition. Master's Thesis. Montreal, Quebec: McGill University. (p. 3). Available from: http://www.mrsp.mcgill.ca/reports/pdfs/Wesak.pdf. Accessed 17 November 2006.

- Narada (1992), p11-12

- Narada (1992), p14

- Narada (1992), p14

- Narada (1992), p15-16

- Narada (1992), p19-20

- Ellora Concept and Style by Carmel Berkson

- The Cambridge History of China, Vol.1, (The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BCE- 220 CE) ISBN 0-521-24327-0 hardback

- K. Sri Dhammananda, Buddhism in the Eyes of Intellectuals

- Gabriel Mandel Khan, "Buddha", Great Biographies. Reader's Digest Association, 1989, ISBN 0-89577-298-1.

- Kamuran Godelek, The Neoplatonist Roots of Sufi Philosophy

- Hazrat Inayat Khan, The Sufi Message. Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass, 2003, ISBN 81-208-0609-3.

- Introduction to Buddhism from an Islamic Viewpoint

Further reading

- Bechert, Heinz (ed.) (1996) When Did the Buddha Live? The Controversy on the Dating of the Historical Buddha. Delhi: Sri Satguru.

- Sathe, Shriram: Dates of the Buddha. Bharatiya Itihasa Sankalana Samiti, Hyderabad 1987.

External links

- Life of the Buddha

- A sketch of the Buddha's Life

- Critical Resources: Buddha & Buddhism

- The Emaciated Gandharan Buddha Images: Asceticism, Health, and the Body

- The Lalitavistara

- Life of Gautama Buddha - Free Audio Books

| Avatars of Vishnu | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dashavatara (for example) |  | |

| Other avatars | ||

| The list of the "ten avatars" varies regionally. Two substitutions involve Balarama, Krishna, and Buddha. Krishna is almost always included; in exceptions, he is considered the source of all avatars. | ||

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: