This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 117.96.187.165 (talk) at 12:52, 19 June 2022 (Some false information was given.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 12:52, 19 June 2022 by 117.96.187.165 (talk) (Some false information was given.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Caste community of India For the village in Estonia, see Koeri, Estonia.Ethnic group

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Bihar | est. 7–8% of the population |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Shakya | |

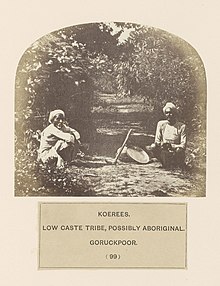

The Koeri (also known as Koiry or Koiri) are an Indian kshatriya caste, found largely in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh . Their traditional occupation was agriculture. According to Arvind they were horticulturist rather than agriculturists. Additionally, Many of koeri were recruited in army under British rule , later in Bihar regiment in independent india. Koeris have attempted Sanskritisation— as part of social resurgence.

During the British rule in India, Koeris were described as "agriculturalists" along with Kurmis and other cultivating castes. The Colonial Era writers had also praised them for being quiet, industrious ,skilled cultivators and brave warrior.

Before the land reforms, Koeris had been peasants and landholder but after the new policies of the Indian government including the land ceiling laws and communist pressure in the 1970s, upper caste landlords resorted to selling off their lands, often to groups of koeris. This allowed the Koeris themselves to aspire to be good landholders. In post-independence India, Koeris have been classified as Upper Backwards by virtue of being part of the group of four of the OBC communities in Bihar, who acquired land overtime, adopted improved agricultural technology and attained political power to become a class of rising Kulaks in the agricultural society of India.

The Koeris are found in Saran district and also live in the Samastipur district of Bihar. Outside India, the Koeris are distributed among the Bihari diaspora in Mauritius where they were taken as indentured labourers. They also have a significant population residing in Nepal.

In 1977, the government of Bihar introduced an affirmative action of quota in government jobs and universities which has benefitted the backward castes like the Koeris. They are classified as a “Backward caste” or “Other Backwards Caste” under the Indian governments system of positive discrimination.

Sanskritisation

Koeris have traditionally been classified as a “shudra“ caste and today Koeris have attempted Sanskritisation—the attempt by traditionally low castes to rise up the social ladder, often by tracing their origins to mythical characters or following the lifestyle of higher varna, such as following vegetarianism, secluding women, or wearing janeu, the sacred thread. The Sanskritising trend in castes of northern India, including that of the Koeris, was inspired by the vaishnavite tradition, as attested by their bid to seek association with avatars of Vishnu. Author William Pinch wrote:

"The nineteenth century antecedents of the Kushvaha- kshatriya movement reveal distinct cosmological associations with Shiva and his divine consort, Parvati. Kushvaha-kshatriya identity was espoused by agricultural community well known throughout the Gangetic north for an expertise in vegetable and (to an increasingly limited scale after the turn of twentieth century) poppy cultivation. Prominent among them were Kachhi and Murao agriculturalist of central Uttar Pradesh ,Kachhvahas of western Uttar Pradesh and Koiris of Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh."

Kushwaha Kshatriya Mahasabha, the caste association of Koeris, held its first session in 1922.

Some Kushwaha reformers like Ganga Prasad Gupta in Banaras argued the Koeris descended from Kusha and that they served Raja Jayachandra in their military capacity during the period of Muslim consolidation under Shuhabuddin Ghuri. He argued further that after defeat, the fear of persecution at the hands of Muslims caused the Kusvaha Kshatriya to flee into the forest in disarray and discard their sacred threads, so as not to appear as erstwhile defenders of Hinduism. The British ethnographer Herbert Hope Risley recorded various Koeri origin myths in the 1890s. According to one of them, Shiva and Parvati created Koeri and Kachhi to take care of vegetables and their flower gardens in Banaras. Writing eighty years later, Francis Buchanan-Hamilton records that Koeris of Bihar were followers of Dashanami Sampradaya while those of Gorakhpur and Ayodhya looked towards Ramanandi saints for spiritual guidance.

According to Christophe Jaffrelot, the caste associations were formed with the basic objective of unifying individual castes. The All India Kushwaha Kshatriya Mahasabha was formed to bring the horticulturist and market gardener communities like the Koeri, the Kachhi and the Murao under one umbrella. The Koeris also attempted to forge a caste coalition called Raghav Samaj, backed by kurmis which was named after one of Rama's names. This was done to justify the communities' claims of descent from Lava and Kusha, respectively. In 1928, the Mahasabha also petitioned the Simon Commission on behalf of various subcastes of the Koeri community to seek recognition as Kshatriya.

The terminology Lav-Kush for the Koeri-Kurmi community became more important in politics than in culture; in Bihar, it came to represent the political solidarity of the Koeri and Kurmi castes.

In context of the communal riots related to cow protectionism, some writers are also of the opinion that low castes groups like Koeri, Ahirs also took to cow protection for asserting higher social status since cow already had symbolic importance in Hinduism. This particular view of cow protection was different from the UP's urban elites.

Economy

The community was at the heart of the Indian opium trade, which had its main base in Bihar. For many years the British East India Company via an agency in Patna regulated and exploited it. Carl Trocki believes that. "Opium cultivators were not free agents" and describes the coercion and financial arrangements that were involved to achieve production, which included restricting land to that product even when the people needed grain because of famine. Although profitable for the company, it was often not so for the peasant producer, and, "Only one particular caste, the Koeris, managed to carry on the cultivation with some degree of efficiency. They were able to do this because they could employ their wives and children to help out with the tasks of opium production."

Other groups involved in opium production had to hire labour, but the Koeris cut costs by utilising that available within their own family. Describing the industrious nature of the Koeri people, Susan Bayly wrote:

"By the mid-nineteenth century, influential revenue specialists were reporting that they could tell the caste of a landed man by simply glancing at his crops. In the north, these observers claimed, a field of 'second-rate barley' would belong to a Rajput or Brahman who took pride in shunning the plough and secluding his womenfolk. Such a man was to be blamed for his own decline, fecklessly mortgaging and then selling off his lands to maintain his unproductive dependents. By the same logic, a flourishing field of wheat would belong to a non-twice-born tiller, wheat being a crop requiring skill and enterprise on the part of the cultivator. These, said such commentators as Denzil Ibbetson and E. A. H. Blunt, were the qualities of the non-patrician 'peasant' – the thrifty Jat or canny Kurmi in upper India, .... Similar virtues would be found among the smaller market-gardening populations, these being the people known as Koeris in Hindustan"

A Report from 1879 pertaining to the Zamindari areas of Hathwa and nearby areas indicates that some of the branches of the koeri community like "Oudhia Koiri" and "Gomta Koiri" were notorious for desertion of their villages. An opinion behind this widespread desertion and frequent mobility was fear of falling in rank from an "independent pleasant", cultivating their own field to "landless labourers", working in the field of others. An observation by Dr. Hunter in some districts of Bihar identified Koiris and Oudhia Kurmis as most respectable of all cultivating castes.

In 1877, there was an attempt by colonial Government of Bengal to prepare an account of Indian society and it culminated into the process of all india social classification of various castes and tribes beginning with the first census of 1871. In 1901, Herbert Hope Risley applied anthropometrical methods to develop a racial taxonomy of Indian society leading to a problematic attempt to classify people of India. The Koeris were classified as "agricultural caste" along with the Kurmis. An official report of 1941 described them as being the "most advanced" cultivators in Bihar and said, "Simple in habits, thrifty to a degree and a master in the art of market-gardening, the Koeri is amongst the best of the tillers of the soil to be found anywhere in India." During the colonial period, in the provinces such as Bengal, although majority of rural population was having a living from the agriculture, only a few of them deserved classification as "agriculturists". The Koeris along with the Kachhis and the Kurmis were not only the major "agricultural caste", but were also reputed as most skilled cultivators. As per the description of William Crooke of the contemporary agrarian society, the Koeris were 'quiet, industrious and well-behaved people'.

In post independence India, Koeris have been classified as upper strata of Backward Castes by virtue of being part of the group of four of the OBC communities in Bihar, who acquired land overtime, adopted improved agricultural technology and attained political power to become a class of rising Kulaks in the agricultural society of India.

Post land reforms

Peasants in middle castes like the Koeris benefitted the most from the land reform policies of the Indian government. Faced with the land ceiling laws and communist pressure in the 1970s, upper caste landlords resorted to selling off their lands. In most cases the buyer would be from the Koeri, the Kurmi, or the Yadav castes. These peasants worked skillfully on their land and made their holdings more productive. In contrast, the upper castes were unable to do so, and they seemed to be satisfied with the price they got for their land. The increased urbanisation among forward castes created a category of new landlords in the countryside as these three middle castes seldom sold their land, rather they looked on reforms as an opportunity to buy more.

This phenomenon promoted the upward mobility of middle peasant castes. While this mobility in the Yadavas consolidated them as both big peasants and landlords, in the Koeris, the vertical mobility was exclusively towards them becoming landlords. The rise of castes like the Koeri, the Kurmi, and the Yadav, and the fall from power of the forward castes was characterised by growing assertiveness among these middle peasants who now acted as the zamindars (rulers) they once condemned.

In 1989, Frankel observed that 95% of the upper castes and 36% of the middle peasant castes like the Koeri and the Yadav belonged to a rich peasant-cum-landlord class. An aversion to manual labour characterised this class. However, some Koeris and Yadavas who held comparatively less land to provide them with subsistence also worked as agricultural labourers, though the bulk of agricultural labourers belonged to the Dalit caste. According to Frankel, the bulk of middle and poor peasantry belonged to castes like the Koeris and the Yadavas; this class worked in their own fields but considered it beneath their dignity to work in others' fields. However, the socio-economic progress and transition towards the upper edge of the social hierarchy was not unabated. The Koeris, like the other middle level castes in north India, were facing a double-edged confrontation from the upper castes who were supporters of the status quo as well as from the Dalits and the lowest castes who now became assertive for their own rights. All this made the middle castes aggressive. Sanjay Kumar associates the political mobilisation of the middle peasant castes, also called upper-OBCs with this gradual process of land reforms undertaken in Bihar in the decades preceding the period of 1970-90. According to Kumar:

Despite all their limitations, the land reform laws since 1948 have transferred ownership right in vast areas of land to upper-OBCs mainly Yadav and Koeri-Kurmi. This gave them strength to ask for a larger share in political power and by the late 1960s, they seemed to have started asserting themselves politically, which is reflected in slow but gradual rise of their representation in Vidhan Sabha (legislative assembly)

The conflict with upper caste landlords led to an attraction towards far-left naxalism. This was witnessed in Ekwari, a village, in the Bhojpur district where Jagdish Mahto, a Koeri teacher, began leading the Maoists and organised the murders of upper caste landlords after he was beaten up by Bhumihars for supporting the Communist Party of India (CPI) in the 1967 elections. Mahto also set up a newspaper in Arrah called Harijanistan. After Mahto was killed in 1971, the communist uprising in Bhojpur subsided.

Later, a section of the upper strata of the Koeris and other middle peasant castes voiced their support for the militant organisation Ranvir Sena. This group had benefitted the most from land reforms and became ruthless towards the Dalits.

Affirmative Action

Koeris are classified as a “Backward caste” or “Other Backwards Caste” under the Indian governments system of positive discrimination, so they are entitled to OBC reservations in govt jobs.

Distribution

Between 1872 and 1921 the Koeris represented approximately seven per cent of the population in Saran district, according to tabulated data prepared by Anand Yang. Yang also notes their involvement in tenanted landholdings around the period 1893–1901: the Koeris worked around nine per cent of the total cultivated area of the district which was one per cent less than the Ahirs, although they represented around five per cent more of the population. According to Christopher Bayly :

"Eighteenth-century settlement of Kurmi, Kacchi and Koeri cultivators were also numerous in northern and western Awadh. On the fringes of cultivation, these castes were given special rental rates for bringing areas of jungle under plough. In the first five years, for instance the rent might be only half of what was common for soil of the same type. The revenue benefits to the entrepreneur or official who planted the colony were very great."

They are also distributed in the Samastipur district of Bihar. In this district the Koeri caste is notorious for their criminal affairs and represent most of the ten legislative assembly seats in this district. In a fieldwork study, where data was collected in 2008-11 by Gaurang R Sahay, the details of 13 villages of Unwas panchayat in the Buxar of South western Bihar which were in close proximity to each other concluded that Koeris had the largest population and were one of the main landholding castes in ten of those villages but the average landholding by the households in the surveyed villages were found to be just 2.12 acres per household. The limited landholding was also found to be unequally distributed in caste and class. Further, another study conducted in some select villages of rural Bihar revealed the Koeris perform the function of a purohit (family priest) and a significant number of houses were seen availing themselves of the services of the purohits of the Koeri caste. During the colonial period, in the provinces such as Bengal, although majority of rural population was having a living from the agriculture, only a few of them deserved classification as "agriculturists". The Koeris along with the Kachhis and the Kurmis were not only the major "agricultural caste", but were also reputed as most skilled cultivators. As per the description of William Crooke of the contemporary agrarian society, the Koeris were 'quiet, industrious and well-behaved people'.

Distribution outside India

Outside India, Koeris are distributed among the Bihari diaspora in Mauritius. Though the island is divided along ethnic and religious lines, 'Hindu' Mauritians follow a number of original customs and traditions, quite different from those seen on the Indian subcontinent. Some castes in Mauritius in particular are unrecognisable from a subcontinental Indian perspective, and may incorporate mutually antagonistic castes into a single group. The 'vaish', which includes the Koeris, is the largest and most influential caste group on the island. The former Brahmin elites together with former Kshatriya are called 'Babuji' and enjoy the prestige conferred by high caste status, though politically they are marginalised.

The Koeris also have a significant population residing in Nepal. The 1991 census conducted there included estimates of their population estimates but these were not included in the 2001 census.

Subdivisions, classification and culture

Castes similar to the Koeri in North India include the Maurya, the Kushwaha, the Mahto, the Kachhi, the Shakya and the Saini have come closer and began intermarrying while developing the all India network to strengthen their caste solidarity. In 1811, the physician Francis Buchanan-Hamilton classified the producer castes of Bihar and Patna - the Koeri, the Gwala, the Kurmi, the Sonar (goldsmith) and even the Kayasthas (a scribe caste) as "pure Shudra". However, due to the advancements in their level of education, the Kayastha community was first among them to challenge their Shudra status and claimed a higher Varna. They were followed by the rest of these communities.

In Mubarakpur, Shivcharan Bhagat —a Koiri (vegetable gardener) and a local Ramanandi had an early influence on Bhagvan Prasad’s religious education. He was also addressed as scribe because of his good command over the Persian language. In the households of the cultivator castes like the Koeris, there was no major segregation of family duties based on gender. Here, both male and female members of the family participated in cultivation- related operations, thus paving the way for egalitarianism and a lack of gender-related discrimination and seclusion. The view of the Koeris regarding their women is portrayed through their (Jati) Caste pamphlet, where Koeri women are described as being loyal to their husbands and having all the qualities of a true Kshatriya woman, who faces the enemy with courage and fights along with her husband rather than being defeated outrightly.

The Kshatriya reform movement in the middle peasant castes which took place during 1890s turned rural Bihar into an arena of conflict. William Pinch claims that castes like the Koeris, the Kurmi, and the Yadav joined the British Indian Army as soldiers. The kshatriyatva or "essence of being kshatriya", was characterised by aggressiveness among these castes, which led to the formation of many caste armies resulting in intercaste conflict.

Organisation

In the interwar years, during a period when there was a general movement among various castes seeking to uplift their status, there was also at least one journal being published for the Koeri community, the Kashbala Kshatriya Mitra, while other interests of the Koeri community is taken care of by the Kushwaha Kshatriya Mahasabha.

Politics

In the heyday of British Raj, the Koeris aligned with the Kurmis and the Yadavs to form a caste coalition-cum-political party called Triveni Sangh. The actual date of the formation of Triveni Sangh is disputed among scholars. This caste coalition fared badly against the Congress party and faced a considerable challenge from Congress's backward class federation. Though politically it was not able to make a significant mark, it remained successful in eradicating the practice of begar (forced labour).

The Indian National Congress continued it's policy of not giving due importance to the demand of upper-OBCs for more political representation and the Koeris along with other OBCs remained unsatisfied in the post independence period as well, when the question of political representation for greater part of society was gaining ground. The Congress's reliance on it's "Coalition Of Extremes", referring to the alliance of Upper Castes, Dalits and Muslims became the prime reason behind the upper-OBC's drive for alternative route to gain political ascendency. The "Coalition Of Extremes" was also favourable for the "Upper Caste" lobby within the Congress as they knew that Dalits being a weak socio-economic group could hardly pose any challenge to their position in the socio-economic sphere unlike the Upper-Backwards.

The period of the 1960s witnessed an improvement in the fortunes of the backward castes in politics, with a significant growth seen in the number of backward caste MLAs in the Bihar legislative assembly. In the 1970s, with the defining slogan of social justice, Koeris rose to prominence in the politics of Bihar under the leadership of Jagdeo Prasad. However, this achievement was short-lived and their representation was gradually lost to other backward castes after Prasad's death. This period also witnessed Satish Prasad Singh, a lesser known Koeri leader, become the chief minister of Bihar merely a week after the fall of Mahamaya Prasad Sinha government. He led a coalition of the Shoshit Samaj Dal party of Jagdeo Prasad and the Congress.

In 1977, the Karpoori Thakur government of Bihar introduced an affirmative action of quota in government jobs and universities. While the lower backward castes were assigned 12% of the quota, only eight percent was earmarked for landowning castes like the Koeri, the Kurmi and the Yadavs. Being a Nai by caste, Thakur was aware of the robust economic position and aggressiveness of these castes who were many times seen bullying the Harijans and lower backwards castes.

In later years, the Koeris remained in a muted position for a long period in politics or played a secondary role, while the Yadav-centric politics of Laloo Yadav flourished in Bihar. However, after the formation of the Samta Party (now Janata Dal (United)) by Nitish Kumar, they voted en masse for Samta. Its alliance showed that political parties in Bihar are identified with caste and the Samta Party was considered the party of Koeri-Kurmi community.

The parting of the ways between the Koeris and the Kurmis and the movement of the Koeris away from Janata Dal (United) (JD(U)) was witnessed after the formation of the Rashtriya Lok Samta Party by Upendra Kushwaha, who commanded huge support among members of the Koeri castes. The Bharatiya Janata Party appealed to the kushwaha in the 2014 elections in hopes of getting the support of the Koeri caste who had earlier voted for Nitish Kumar and the JD(U). However, the quitting of BJP and alliance by Upendra Kushwaha left Koeri politics in Bihar in a dilemma. This rift between the Koeris and the Kurmis was orchestrated by the rise of influential Koeri leaders like Mahendra Singh and Shakuni Choudhury, while Kushwaha remained the strongest leader of the community in Bihar.

In 2010s, attempts to trace the community's lineage to Mauryan king Ashoka were supported by Bharatiya Janata Party and Janata Dal (United) with an apparent eye towards the electoral benefits, particularly in North Indian states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

See also

References

- "उत्तर प्रदेश चुनावः कितने ताक़तवर हैं स्वामी प्रसाद मौर्य?". BBC News हिंदी (in Hindi). Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- Das, Arvind N. (1992). The Republic of Bihar. Penguin Books. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-14-012351-7.

- Raman, Vasanthi (2012). The Warp and the Weft: Community and Gender Identity Among the Weavers of Banaras. Routledge. p. 109. ISBN 9781136518003.

The fact that weavers in Banaras are still predominantly Muslim (particularly in the highly skilled silk weaving domain) and the traders and buyers still predominantly Hindu constitutes the basis for interdependence between the two communities. However, many Hindu lower-caste groups (particularly Koeris, Mallahs, Mauryas, and even Yadavs) and some Dalit groups have also taken to the occupation of weaving. The large majority of Momin Ansaris are still ordinary weavers, trying to eke out a livelihood in very straitened circumstances.

- Uttar Pradesh District Gazetteers: Bijnor. Government of Uttar Pradesh. 1989. p. 56.

- Claveyrolas, Mathieu (2013). "The 'Land of the Vaish'? Caste Structure and Ideology in Mauritius". Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions: 191–216. doi:10.4000/samaj.3886.

- Sharma, Shalendra (1999). Development and Democracy in India. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 157. ISBN 9781555878108.

Upper of forward caste(brahmin thakur bania kayastha), cultivating or middle castes(jat bhumihar tyagi), lower shudra or backward caste(yadav, kurmi, lodh koeri gujar kahar gadaria teli harhai nai kachi others), scheduled castes(chamar pasis dhobi bhangi)

- Omvedt, Gail (18 June 1993). Reinventing Revolution: New Social Movements and the Socialist Tradition in India. M.E. Sharpe. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-7656-3176-3.

But in eastern U.P. and Bihar, marked much more by landlordism and within this the domination of the "twice-born" upper castes (brahmans, bhumihars, and rajputs), even the "shudra" peasant castes (kurmis, koeris, and yadavas) were cruelly subordinated, and there had been little of a broad anticaste movement.

- N. Jayapalan (2001). Indian society and social institutions. Atlantic Publishers & Distri. p. 428. ISBN 978-81-7156-925-0. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. p. 91,92. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- ^ Kumar, Ashwani (2008). Community Warriors: State, Peasants and Caste Armies in Bihar. Anthem Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-84331-709-8.

The Koiris are known as great horticulturists and engage primarily in agricultural operations in the capacity of small landowners and poor peasants. Unlike Kurmis and Yadavs, they are generally considered non aggressive and disinterested in caste riots. They also attempted to attain higher social status by claiming to be descendants of Lord Ram's son Kush. They formed the Kushwaha Kshatriya Mahasabha as their nodal caste association and held the first session of the association in March 1922.

- Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. London: C. Hurst & Co. pp. 197–199. ISBN 978-1-85065-670-8. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- Banerjee, Mukulika (2017). Why India Votes? :Exploring the Political in South Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317341666. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Gould, William (2012). Religion and Conflict in Modern South Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-521-87949-1.

Gyan Pandey's detailed research on the cow protection riots in eastern UP and Bihar in 1893 and 1917 relates the conflict to specific registers of caste difference and status assertion, in a context where the popular view of cow protection from the point of view of low-caste Ahirs, Koeris and Kurmis was quite different to that of UP's urban elites. For both Freitag and Pandey, cow protection became a means for relatively low-status communities to assert higher status via association with something of symbolic importance to Hinduism as a whole: in this case, the cow.

- ^ Trocki, Carl A. (1999). Opium, empire and the global political economy: a study of the Asian opium trade, 1750–1950. Routledge. pp. 64–67. ISBN 978-0-415-19918-6. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521798426. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Anand A. Yang (2021). The Limited Raj Agrarian Relations in Colonial India. University of California Press. p. 187-188. ISBN 978-0520369108. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ Rolf Bauer (2019). The Peasant Production of Opium in Nineteenth Century India. BRILL. p. 143. ISBN 978-9004385184. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. London: C. Hurst & Co. p. 197. ISBN 978-1-85065-670-8. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- Carolyn Brown Heinz (3 June 2013). Peter Berger; Frank Heidemann (eds.). The Modern Anthropology of India: Ethnography, Themes and Theory. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-06118-1.

The four dominant high caste groups (the forward castes)-Brahman, Bhumihar, Rajput, Kayastha-together constitute about 12 percent of the population. These are the old elite, from whose numbers came the major zamindars and land owning castes. The so-called Backward castes consisting of about half the population of Bihar, were further classified soon after independence into Upper Backward and Lower Backwards(Blair 1980). The upper backwards - Bania , Yadav, Kurmi and Koiri - constitute about 19 percent of the population, and now include most of the rising Kulak class of successful peasants who have acquired land, adopted improved agricultural technology, and become a powerful force in Bihar politics. This is true, above all, of the Yadavas. The lower backwards are shudra castes such as Barhi, Dhanuk, Kahar, Kumhar, Lohar, Mallah, Teli etc, about 32 percent of the population. The largest components of the scheduled castes(14 percent) are the Dusadh, Chamar, and Musahar, the Dalit groups who are in many parts of the statelocked in struggles for land and living wages and living wages with the rich peasants and landlords of the forward and upper backward castes

- Sinha, A. (2011). Nitish Kumar and the Rise of Bihar. Viking. p. 80,81. ISBN 978-0-670-08459-3. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- Reddy, D. Narasimha (2009). Agrarian Reforms, Land Markets, and Rural Poor. Concept Publishing Company. p. 279. ISBN 978-8180696046. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Sinha, A. (2011). Nitish Kumar and the Rise of Bihar. Viking. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-670-08459-3. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- Kunnath, George (2018). Rebels From the Mud Houses: Dalits and the Making of the Maoist Revolution ... New York: Taylor and Francis Group. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-138-09955-5. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Ram, Nandu (2009). Beyond Ambedkar: Essays on Dalits in India. Har Anand Publications. p. 32. ISBN 978-8124114193. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Kumar, Sanjay (27 May 2022). Post mandal politics in Bihar:Changing electoral patterns. SAGE publication. p. 31. ISBN 978-93-528-0585-3.

- Omvedt, Gail (1993). Reinventing Revolution: New Social Movements and the Socialist Tradition in India. M.E.Sharpe. p. 59. ISBN 0765631768. Retrieved 16 June 2020. "Its first mass leader was Jagdish Mahto, a Koeri teacher who had read Ambedkar before he discovered Marx and started a paper in the town of Hrrah called Harijanistan("dalit land")..

- Samaddar, Ranbir (2019). From popular movement to rebellion:The Naxalite dacade. New york: Routledge. p. 317,318. ISBN 978-0-367-13466-2. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Kalpana, Nira-Yuval-Davis (2006). The situated politics of belonging. london: Sage Publications. p. 135,136. ISBN 1-4129-2101-5. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Mukherji, Partha Nath (2019). Understanding Social Dynamics in South Asia: Essays in Memory of Ramkrishna Mukherjee. Springer. p. 28. ISBN 9789811303876.

- Yang, Anand A. (1989). The limited Raj: agrarian relations in colonial India, Saran District, 1793–1920. University of California Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-520-05711-1. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- Bayly, C. A. (1988). Rulers, Townsmen and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion. Cambridge University Press. p. 101. ISBN 0521310547. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Thakur, Minni (2010). Women Empowerment Through Panchayati Raj Institutions. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-8180696800. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- N. Jayaram, Partha Nath Mukherji (2019). Understanding Social Dynamics in South Asia. Springer Publishing. p. 88-99. ISBN 978-9811303876. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Sharma, K. L. (2013). Readings in Indian Sociology: Volume II. India: SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-8132118725. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Bates, Crispin (2016). Community, Empire and Migration: South Asians in Diaspora. Springer. p. 14. ISBN 978-0333977293. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Mandal, Monika (2013). Social Inclusion of Ethnic Communities in Contemporary Nepal. KW Publishers. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-93-81904-58-9.

- Patel, Mahendra Lal (1997). Awareness in Weaker Section: Perspective Development and Prospects. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 37. ISBN 8175330295.

- ^ Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. pp. 73–75. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

Buchanan, in the early nineteenth century, had included in the term "pure shudra" the well-known designations of Kayasth, Koiri, Kurmi, Kahar, Goala, Dhanuk (archers, cultivators, palanquin bearers), Halwai (sweets vendor), Mali (flower gardener), Barai (cultivator and vendor of betel-leaf), Sonar (goldsmith), Kandu (grain parcher), and Gareri (blanket weavers and shepherds).108. Buchanan, Bihar and Patna, 1811–1812, 1:329–39; Martin, Eastern India, 2:466–70

- Jassal, Smita Tewari (2001). Daughters of the Earth: Women and Land in Uttar Pradesh. Manohar. p. 71,53. ISBN 8173043752. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- kunnath, George (2018). Rebels From the Mud Houses: Dalits and the Making of the Maoist Revolution ... New york: Taylor and Francis group. p. 209,210. ISBN 978-1-138-09955-5. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Gould, William (2004). Hindu nationalism and the language of politics in late colonial India. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-521-83061-4. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

In the inter-war period religious community was rendered an important site of public political contestation in periodicals and journals. Newspaper publicity, and the symbolism it employed, created and re-created communal stereotypes. 'Communal' controversy, as the early journalistic career of Muhammad Ali who publicised the Kanpur mosque dispute of 1913 demonstrates, was sensational and sold newspapers, causing periodicals to rise and fall. For example, Arti, a Hindi daily from Lucknow, which reached a high circulation of 3,000, was started specifically in response to communal disputes centred around Aminabad Park in the city. The Arya Mitra, a Hindi weekly published from Agra, served as the organ of the Arya Pratinidhi Sabha, which sought to promote shuddhi and the uplifting of the depressed class. The Bharat Bhol was supported by the Rishikesh fund to further agitation over a temple in Dehra Dun. Caste-based journals were also common, such as the Kshattriya, set up to support social reform amongst the Jats of Meerut, the Kashbala Kshattriya Mitra, which promoted the interests of the Koeri community and the Jatava of Agra, which supported the interests of 'untouchables'.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India (Reprinted ed.). C. Hurst & Co. pp. 197–198. ISBN 978-1-85065-670-8.

- Kumar, Ashwani (2008). Community Warriors: State, Peasants and Caste Armies in Bihar. Anthem Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-84331-709-8.

- Kumar, Sanjay (27 May 2022). Post mandal politics in Bihar:Changing electoral patterns. SAGE publication. p. 53. ISBN 978-93-528-0585-3.

If any (class/caste) could compete with the upper castes in terms of the social, economic, and political muscle, it was these three upper backward castes—Yadavs, Kurmis, and Koeris. The social coalition of the 1980s was much more politically oiled than the coalition of 1930, during the days of "Triveni Sangh".

- Vardhan, Anand. "Caste, land and quotas: A history of the plotting of social coalitions in Bihar till 2005". Newslaundry.com. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- Kumar, Sanjay (5 June 2018). Post mandal politics in Bihar:Changing electoral patterns. SAGE Publication. ISBN 978-93-528-0585-3.

- Political Science Association, Delhi University (1981). Teaching Politics, Volume 6 - Volume 7, Issue 4. Delhi University Political Science Association(Original from the University of Michigan). Retrieved 22 June 2020. In 1969, Bindeshwar Prasad Mandal, a rich landlord Yadav of Saharsa district in manipulating some M . L . A ' s to defect from U . F . Parties to cause the fall of Mahamaya Ministry, asked Satish Prasad Singh a lesser known Koeri leader to head the ministry for a day to facilitate his nomination in the Council.

- Bijender Kumar Sharma (1989). Political Instability in India. Mittal Publications. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-81-7099-184-7. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- Thakur, Baleshwar (2007). City, Society, and Planning: Society. University of Akron. Department of Geography & Planning, Association of American Geographers: Concept Publishing Company. p. 397 ,398. ISBN 978-8180694608. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Thakur, Baleshwar (2007). City, Society, and Planning: Society. University of Akron. Department of Geography & Planning, Association of American Geographers: Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-8180694608. Retrieved 16 June 2020. While Samta with its leader Nitish is considered to be the party of Koeri-Kurmi, Bihar people's party led by Anand Mohan is perceived to be a party having sympathy and support of Rajputs.

- Shah, Ghanshyam (2004). Caste and Democratic Politics in India. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 8178240955. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Wallace, Paul (2015). India's 2014 Elections: A Modi-led BJP Sweep. India: SAGE Publications. p. 127,129. ISBN 978-9351505174. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- KAUSHIKA, PRAGYA (10 December 2018). "Upendra Kushwaha's exit could undo BJP's carefully planned Bihar caste coalition". theprint.in. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Ramesh, P. R. (15 October 2015). "The Liberation Struggle of Bihar". Open Magazine. Retrieved 30 April 2020. The real migraine for the JD-U led alliance is the emergence of strong leaders within the NDA who command Kushwaha loyalties as effectively as Ashok Mahto once did for the fight against Bhumihars in the past. Rocking the Grand Alliance's prospects are Kushwaha leaders such as Upendra Kushwaha, Shakuni Chaudhury and Mahendra Singh.

- Tewary, Amarnath (22 April 2022). "BJP celebrates emperor Ashoka's birth anniversary in Bihar". The Hindu.

- Singh, Abhay. "BJP banking on votes of Koeris". The Times of India. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- Vij, Shivam. "Caste groups are burning Rajnath Singh's effigies as he called Chandragupta Maurya shepherd". theprint.in. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

Further reading

- Sanjay Kumar, Christophe Jaffrelot (2012). Rise of the Plebeians?: The Changing Face of the Indian Legislative Assemblies. Routledge. ISBN 978-1136516610. Retrieved 30 June 2020.