This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 72.89.212.50 (talk) at 03:05, 28 February 2007 (←Undid revision 111047173 by Jfdwolff (talk) Let's talk about it b4 you make such a brash move). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 03:05, 28 February 2007 by 72.89.212.50 (talk) (←Undid revision 111047173 by Jfdwolff (talk) Let's talk about it b4 you make such a brash move)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Hasidic Philosophy or Chassidic philosophy (also Hasidism or Hassidism, Chassidus or Chassidut or Chasidut) is the teachings and philosophy underlying Hasidic Judaism.

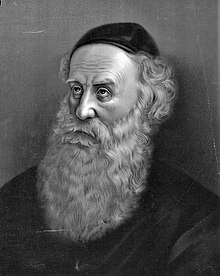

Rabbi Yisroel ben Eliezer (The Baal Shem Tov), introduced these teachings and founded the Hasidic movement. His disciples, most notably Rabbi Dovber of Mezeritch, spread and developed the philosophy. Of all Hasidic groups, the leaders of Chabad (Lubavitch) developed these teachings with explanations far more lengthy and elaborate than those found in the texts of other groups, and stressed the constant, in-depth study of these teachings the most (one example of where this is reflected is in the practice of Chabad yeshivot to study Chassidic philosophy for 3 hours a day, unlike the yeshivot of any other Chassidic group). According to Chabad, understanding these concepts is the only way to truly achieve the goals of Hasidism.

Hasidic Philosophy teaches a method of contemplating on God and His greatness (see Jewish meditation), as well as the inner significance of the Mitzvos (commandments and rituals of Torah law). It is a highly contemplative approach to Torah. This understanding is meant to refine one's character, improve one's interpersonal relations, and add life, vigor and joy to one's religious observance. Ultimately, these claim to be a preparation for the Messianic Era.

Goals of Hasidic Philosophy

Hasidic Philosophy has four main goals:

1. Revival: At the time when Rabbi Yisrael Ba'al Shem Tov founded Hasidism, the Jews were physically crushed by massacres (in particular, those of the Cossack leader Chmelnitzki in 1648-1649) and poverty, and spiritually crushed by the disappointment engendered by the false messiahs. This unfortunate combination caused religious observance to seriously wane. This was especially true in Eastern Europe, where Hasidism began. Hasidism came to revive the Jews physically and spiritually. It focused on helping Jews establish themselves financially, and then lifting their moral and religious observance through its teachings.

2. Piety: A Hasid, in classic Torah literature, refers to one of piety beyond the letter of the law. Hasidism demands and aims at cultivating this extra degree of piety.

3. Refinement: Hasidism teaches that one should not merely strive to improve one's character by learning new habits and manners. Rather a person should completely change the quality, depth and maturity of one's nature. This change is accomplished by internalizing and integrating the perspective of Hasidic Philosophy.

4. Demystification: In Hasidism, it is believed that the esoteric teachings of Kabbalah can be made understandable to everyone. This understanding is meant to help refine a person, as well as adding depth and vigor to one's ritual observance.

In general, Hasidism claims to prepare the world for Moshiach, the Jewish Messiah, through these four achievements.

In a letter, the Ba'al Shem Tov describes how one Rosh Hashana his soul ascended to the chamber of Moshiach, where he asked Moshiach, "when will the master (Moshiach) come." Moshiach answered him, "when the wellsprings of your teachings, which I have taught you, will be spread out."

Essentials of Hasidic Philosophy

Hasidic Philosophy is the knowledge of God, which Hasidic philosophy maintains is the essence of the Torah and of everything in the world. Hassidic Philosophy (along with Kabbalah) is also known as Pnimiyut HaTorah, the Inner Dimension of the Torah. The first premise of Hasidic Philosophy is God and His unity: That God transcends everything and, yet, is found in everything. God transcends all forms and limitations, even the most sublime. To God all forms are equal, and so His intents can be discovered in all of them equally. All existence is an expression of His Being. In the Baal Shem Tov's words, "God is everything and everything is God."

(This is a very subtle and difficult subject, based on the idea of Tzimtzum, and different from both pantheism and panentheism.)

This premise means that everything is an infinite revelation of God, even the smallest and most trivial thing. This basic axiom leads to four points which are the pillars of the Ba'al Shem Tov's approach:

1. Torah: According to the Ba'al Shem Tov the Torah is all God's "names." This means that every detail of the Torah is an infinite revelation of God, and there is no end to what we can discover from it. Just as God is infinite so is the meaning of the Torah infinite.

The Ba'al Shem Tov often explains a verse or word in unconventional, and sometimes contradictory ways, only to show how all of these interpretations connect and are one. The Baal Shem Tov would even explain how all of the combinations of a word's letters connect.

2. Divine Providence:

- a.) According to the Ba'al Shem Tov every event is guided by Divine Providence. Even the way a leaf blows in the wind, is part of the Divine plan.

“b.) Every detail is essential to the perfection of the entire world. If things weren't exactly this way, the entire Divine plan would not be fulfilled.

- c.) This Divine purpose is what creates and gives life to this thing. Thus, its entire existence is Divine.

Based on this, the Ba'al Shem Tov preached that one must learn a Godly lesson in everything one encounters. Ignoring His presence in every factor of existence is seen as a spiritual loss.

3. Inherent Value: The Ba'al Shem Tov teaches that even a simple Jew is inherently as valuable as a great sage. For all Jews are "God's children" (Deuteronomy 14:1), and a child mirrors his father's image and nature. And, just as God is eternal and his Torah and Commandments are eternal, so are his people eternal. Even the least Jew is seen as a crown that glorifies God.

4. Brotherly Love: The command to love another, according to the Baal Shem Tov, does not mean simply being nice. Rather, one must constantly strive to banish negative traits and cultivate good ones. This command encompasses one's entire life.

Other aspects of the Ba'al Shem Tov's approach: One should strive to permanently rectify negativity and not just suppress it. The effort in one's divine service is most important. If God wanted perfection, He would not have created us with faults and struggles. Rather, God desires our effort and struggle and challenges.

Hasidic Philosophy and the other levels of Torah

Classic Jewish teachings interpret the Torah (and sometimes, all other Jewish Scriptures) on four levels. They are:

-Pshat: Plain meaning of the text

-Remez: Hinted Meaning, how something in Torah relates to something larger in the world

-Drush: The Mitvos and moral lessons. From the word Doresh-what the Torah demands morally

-Sod: Kabbalah; Deep and mystical secrets of the Torah

Hasidism does not consider itself the 5th level of learning the Torah, but rather brings out the "essence" of all those 4 levels, appreciating the Godliness in each level and how all the levels connect. This means that even someone at a low level of appreciation of the Torah (e.g. he is on the level of Pshat) can still have an appreciation of Hasidism because it reveals the inherent essence in all the levels. Hasidism also provides the tools for the intellectual and theoretical understanding to be applied to practical life.

Chassidus seeks Godliness in everything.

Hasidism vs. Musar

Musar helps a person to appreciate the intellectual and spiritual and Godly matters to decrease attachment to the bodily and physical things. Hasidism responds that as much as one will run from physical things, one can never truly succeed in this because we are found in a physical world. Hasidism teaches that, ultimately, one must have both the spiritual and the physical together to prosper in one's service of God. This is a two step process. First one must be able to appreciate the spiritual and Godly, but then one must connect this inspiration back to seeing Godliness in the mundane world. Therefore, physicality is not suppressed, but transformed, such that it is not differentiated from divinity but is filled with it, as it serves it.

The key to all wisdom

Hasidism offers an analogy to explain the difference between learning Hasidism and other parts of the Torah. It was once asked: What is the difference between Rambam and Aristotle? Torah vs. Wisdom. Both are philosophers and scientists. The answer was that Aristotle is like a person trying to draw a circle and find its center. This is a difficult job. The Torah, by contrast, starts with the center then goes and can make a circle of any size around it, and it will always be in the center. Likewise, once one grasps Hasidism, it is believed that he will have the key to all the other aspects of the Torah because he will understand its underlying message. Once the inner point of the Torah is grasped (the middle of the circle) the only job is then to learn how to put it into practice in daily life which is what the other levels teach a person to do.

Connection to the Jewish Messiah

Hasidism tries to find the good in everything. It does not say that the bad becomes good, but rather that in the bad itself - in the struggle - we find Godliness.

This is synonymous with the concept of Moshiach which is an era in which even things we saw as being bad we will see as being good. Life before the times of the Jewish Messiah and redemption are compared to characters living within the story. But with Moshiach we will see things from outside of the story and see how we are all like actors and God is directing the show. Outside the story, even the bad is good because the struggle is what makes the story worth reading.

We are like actors, can express freely, not trapped by the particular character we are playing. Really one can act freely with the mask. We make this self-image, thinking that we have our certain qualities and self-imposed limitations, and this stops us from expressing our true selves.

Hasidism wants us to get in touch with that essence so we are able to act in the world with whatever character is best at the time. In this way a person can come in touch with his real self and be free to choose how to act.

Hasidism tries to give us a taste of Moshiach-and bring this type of awareness into the world which itself will bring Moshiach by bringing a personal redemption to each person.

The Ba'al Shem Tov maintained that God is everything and everything is God. Torah is considered all the names of HaShem (God), not anything definite just the way you call them. So too Torah is considered infinite; one can always see more and more revealing an infinite God.

Hasidic philosophy also reemphasizes and expands upon the Jewish belief in Divine Providence. Before the Ba'al Shem Tov there was the general idea that God is watching over us. The Ba'al Shem Tov said that not only is God watching over everything, but even a feather in the wind and other seemingly minute details have infinite importance and are essential to the entire existence of creation.

Since, according to Hasidism, God is choosing everything that happens in the world without any external influences that he wants exactly like that, therefore everything that goes on is a unique expression of Him.

The purpose of Torah and Mitzvos is seen as only a revealing of that connection, not creating it (like father and son-the son may walk more or less in his father's footsteps, but this will never change the fact that he is his son. This is an essential connection).

Hasidic philosophy also stresses the concept of love of the fellow Jew. According to Hasidic philosophy, loving another fellow Jew is not just a good character trait but rather it should be one's whole life’s work to cultivate good character traits.

Various Schools of Hasidic Philosophy

There is Chabad philosophy which traces its roots back to Maggid of Mezeritch (disciple of the Baal Shem Tov) through the dynasty of the seven Hasidic masters of Chabad which began with Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi. However, there were other disciples of the Maggid, and there are other hasidic sects which have their own way of learning hasidic philosophy such as Breslov hasidim who follow the teachings of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov. Generally, hasidic philosophy is categorized as either Chabad (an acrostic which refers to the intellectual faculties of the soul) or Chagas (an acrostic which refers to the emotional attributes of the soul). These classifications represent a difference in opinion as to how Hasidic philosophy should be learned. Those of the Chabad school of thought believe that hasidic philosophy is to be learned in an in-depth and intellectual way, while those of the Chagas school of thought believe that the main thing is to achieve emotional excitement which will come mainly through our attachment to the Tzaddik (righteous individual) and not so much through our own efforts. This difference in approach may account for the fact that Chabad philosophy has published a greater volume of texts in hasidic philosophy as compared to the other hasidic groups, and why Chabad is the only of the hasidic groups that has made study of hasidic philosophy a mandatory and substantial part of their yeshiva curriculum.

The most popular work of Chabad hasidic philosophy is the Tanya. Some popular works of other Hasidic philosophies include Noam Elimelech, Kedushas Levi, Bnei Yisoschor, Shem MiShmuel, Ma’or V’Shemesh, Be’er Mayim Chayim, and Likutei Moharan. Chabad philosophy was more commonly found in Russia, while Chagas philosophy was more prevalent in Poland, which is why it is sometimes referred to as "Polish Hasidism".

See also

See Glenn Dynner, "Men of Silk: The Hasidic Conquest of Polish Jewish Society" (NY: Oxford University Press, 2006)

External links

Source: On the Essence of Chassidus by Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Kehot Publications Brooklyn 1998

Categories: