This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Sohanigohal (talk | contribs) at 14:41, 30 December 2022 (we gave a brief definition of minor subjects, that include property dualism and we also gave a detailed explanation nd definition of what property dualism truly is.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 14:41, 30 December 2022 by Sohanigohal (talk | contribs) (we gave a brief definition of minor subjects, that include property dualism and we also gave a detailed explanation nd definition of what property dualism truly is.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)THE ARGUMENT FROM DOUBT

For Descartes’s research and beliefs to be certain, he had to get rid of all beliefs that were uncertain and doubtful. The philosopher is aware that there is nothing to be certain of in life, like the existence of the world around him or even of his own existence. However, for him to be deceived with reality, he himself must in contrast be real. He supports this with his famous principle cogito ergo sum, “I think, therefore I am”. This reasoning allows him to understand that he can doubt the existence of physical entities, such as his body, but he cannot doubt the existence of his consciousness.

- The cartesian description of dualism is substance dualism. It is an idea that we are mental things, and we inhabit a physical body and minds somehow interact with the physical body. Our mind, which is its own substance, tells our physical body what to do and our body transmits information to the mind.

- We do gain info from our senses, and we transmit information to our bodies.

Qualia: EX: if it feels like pain, then it pains. It is a subjective experience.

ASSESSING THE ARGUMENT FROM DOUBT

Descartes’s argument from doubt is an effective argument to support this philosophy. To further defend this argument, a method often used to distinguish two individuals or things is to find their differences. This essentially means that you must find a property that only one of the two individuals or things is in possession of, that the other lacks. The Leibniz’ Law principle, often referred to as the principle of the indiscernibility of identicals , essentially states that identical entities share the exact same properties. Furthermore, it is known that the mind and the body are not identical since they do not share the same properties. Their difference with respect to dubitability leads us to question whether their existence can be doubted. However, considering this Argument from Doubt is an observer-relative one, and both Descartes’ mind and body have nor lack the property of dubatibility, we can conclude that the Argument from Doubt has not been proven successful.

THE CONCEIVABILITY ARGUMENT

Descartes’ conceivability argument mainly revolves around the existence of God and his belief about God’s existence. His questioning of the mind and the body is done using the Sixth Meditation, a meditation that defines “The existence of material things and the real distinction between mind and body.” Descartes’ argues that for Dualism to be successful, we must assume and understand the mind apart from the body.

This concept relates to God in the sense that everything we can certainly understand can be created by God. Clearly understanding different things can be enough for us to clearly understand things or individuals being distinct and separate from one another by God.

Descartes’ standard form of the conceivability arguments assumes the following:

- Whatever is clearly and distinctly conceivable is possible.

- I can clearly and distinctly conceive the mind existing without the body.

- Thus, it is possible for the mind to exist without the body.

- If it is possible for A to exist without B, then A and B are distinct entities.

- Thus, the mind and the body are distinct entities, i.e., dualism is true.

This argument is essentially supported with the belief that claims that was is conceivable is tied to what is possible.

ASSESSING THE CONCEIVABILITY ARGUMENT

The conceivability argument can be interpreted differently from person to person. Not everyone will perceive something the same as everyone else, but like Descartes’ notes, one must perceive something clearly and distinctly as noted in premise 1. To understand all premises, the first premise must be clearly understood.

THE DIVISIBILITY ARGUMENT

The divisibility argument looks more into the nature of the body and its ties to the mind. He writes, “There is a great difference between the mind and the body, inasmuch as the body is by its very nature always divisible, while the mind is utterly indivisible.”

This argument assumes the following:

- The body is divisible.

- The mind is not divisible.

- If the mind and the body differ with respect to their properties, then the mind is a different thing from the body.

- Thus, the mind is a different thing from the body.

Just the argument from doubt, the divisibility argument uses Leibniz’ Law strategy. However, both arguments utilize different properties, the Argument From Doubt relied on Dubitability which is observer-relative, whereas the Divisibility Argument relies on the physical property of divisibility.

ASSESSING THE DIVISIBILITY ARGUMENT

The divisibility argument contains certain weaknesses regarding the employment of divisibility. Unlike other physical beings, the body is incapable of being divided into two separate and complete bodies. Despite this, the body is capable of being divided into separately identifiable entities. In this sense, we can affirm the first premise by concluding that the brain is divisible into different segments, such as the left and the right hemisphere. As for the second premise, Descartes’ supposes that the mind can be divided into different faculties such as the faculty of will, of understanding, of sense perception, etc. However, Descartes’ views the mind as a whole, as a unified consciousness that is immaterial. Furthermore, any part of the body could theoretically continue to exist independently, but consciousness and all its faculties need to exist as a whole to be considered existent. However, we could also consider the mind to be separated into the conscious and the unconscious mind, or even separate streams of consciousness.

INTERACTIONISM

Observations made by Descartes, which is known as interactionism, is explained as interactions and or events calculated by the mind will lead to an interaction with the body. When your mind wants something, your body will do something to make it happen. The same thing happens but vice versa, events that happen to the body will cause an interaction with the mind. When you are injured, your body sends signals to your brain, which then let your brain know that you are in pain. It will then find a solution, to go through a healing process.

ASSESSING INTERACTIONISM

Considerations were brought upon by Princess Elisabeth. The view of descartes minds being an immaterial substance which leads to the confusion of why the mind interacts with the body which is an immaterial substance. It is also mentioned that the mind cannot have physical contact with the mind. This philosophy is known as Princess Elisabeths objection.

The second objection is called causal closure. Years before, there was no scientific answer of why things happen. Now, as we advance in technologie. We now have answers of why some things happen around the world. For example, it was interpreted that they thought that God was sending thunder and rain. In reality it is caused by something more complex than just God.

It is also included that when your brain desires something your body will evidently do it. The final objection is called Epiphenomenalism. Which is the substitute of interactionism. Once the mind has no causal power, there is no longer any connection to the brain.

THE PAIRING PROBLEM

The pairing problem emphasizes that they are two types of substances. Which are the material/physical and the mental/immaterial. From a dualistic view the mind has no location since it is immaterial. Descartes believes connection is from the mind to the physical body by the pineal gland. When this observation was first addressed, it would have answered the pairing problem. Sadly for Descartes, the pineal gland has been located in the body, as a source that “ secretes melatonin and thereby regulates the body's circadian rhythms.” (Kind, 39)

Essentially leaving the pairing problem unsolved. However, Descartes denies that the pairing problem should be added as another problem since there is a much more important problem. Which is the nature of immaterial substances.

CONTEMPORARY VERSIONS OF DUALISM

In an article from Harper's Magazine, Journalist Christopher Beha argues that;

If the sciences had made no headway since Descartes in the effort to understand human consciousness, it might be possible to preserve his distinction , neurologists, psychologists, and cognitive scientist have learned more than enough to convince them that the mind is the physical brain, or at least a function of it, and that no additional mental substance or thinking thing exists. (Beha 2017)

We now comprehend which areas of the brain are in charge of specific functions. Speech, spatiotemporal coordination, and higher order cognition are all examples of basic life functions. Additionally, our knowledge of perception, memory formation, and memory retrieval has advanced significantly. Even in the twenty-first century, some people continue to hold the outdated belief in dualism. For the most of the twentieth century, dualism was rarely brought up in serious philosophical conversations; it was only brought up once again in the 1980s and 1990s. The reflection on qualia was how it began. Qualia is the phenomenal aspect of our four mental states. Science can explain many psychological processes that clarify why things happen the way they do, but it does not appear to be able to explain why things feel the way they do.

Take pain as an illustration. Science can address the difficulty of fully explaining the neural mechanisms associated with pain and the purpose that pain serves in the human system. But science does not appear to be well-suited to address the issue of explaining why these brain activities are accompanied by that specific ouchy sensation—or why they are associated with any feeling at all. Pain seems to reside outside of the world of objectivity that science can engage in.

It is preferable to interpret many of the qualia-based concerns that were expressed in the late twentieth century as arguments of against the physicalist and functionalist viewpoints that had predominated in the middle of the century. One might be persuaded to reconsider adopting a dualist perspective after observing what these beliefs omit.

PROPERTY DUALISM

Descartes and other dualists think that there is an immaterial, non-physical substance that exists. These things are typically described negatively: they are not made of matter, they don't have a physical state, they do not take up space, etc.It is a concept that is veiled in mystery as a due the fact that we are not typically given positive representations of it. Property dualists disprove the notion that there are essentially two distinct types of substances in the world in order to avoid this enigma and other issues.

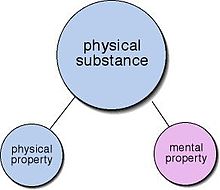

The mind and the physical brain. As an alternative, property dualists argue that there are actually two distinct categories of properties. Even if some objects, like rocks, solely have physical characteristics, other things with physical characteristics, like the human brain, can also have non-physical characteristics. These non-physical characteristics include mental states.

THE ZOMBIE ARGUMENT

The term zombie is used by philosophers. A creature that resembles a human both physically and behaviourally. The zombie and its human twin are the same microphysically. In contrast to their human counterparts, zombies are utterly devoid of perceptual consciousness.

The Zombie Argument:

- Zombies, creatures that are microphysically identical to conscious beings but that lack counsciousess entirely, are conceivable.

- If zombies are conceivable then they are possible.

- Therefore, zombies are possible.

- If zombies are possible, then consciousness is non-physical.

- Therefore, consciousness is non-physical.

When dualist philosophers argue that zombies are plausible, they are basing this assertion on the idea of logical possibility rather than physical possibility.Something needs to be compatible with the laws of physics in order to be regarded as physically conceivable. As a result, something must not only be physically possible but also consistent with the laws of logic in order to be logically possible.

ASSESSING THE ZOMBIE ARGUMENT

Non-dualist philosophers typically pursue one of three lines of objections:

- Whether zombies are actually conceivable has been questioned by some philosophers.

- Some acknowledge the conceivability of zombies but disagree that it is reasonable to advance to a claim about their likelihood.

- Others concede the existence of zombie but contest the notion that this reveals anything about the nature of consciousness.

Many philosophers focus on the first premise and adopt a similar approach to Arnauld's against Descartes. Briefly stated, they contend that we are incorrect in believing that we are truly conceiving what we perceive we are to be.

It suffices for the opponent to point out that there can be a concealed conceptual confusion present in the background when denying the possibility of zombies. According to Chalmer in his book The Conscious Mind (Chalmer 1996), the opponent must provide some context for what conceptual confusion entails. However he still adds that the opponent can support their argument in premise 1 in a number of different ways.

As was previously indicated, non-dualist philosophers have raised several types of objections against the zombie argument in addition to the denial of the conceivability of zombies. Duellist's ability to appropriately address this point does not prove that the argument is valid. However, I t is fair to say that the zombie argument is currently a controversial one that is still going on.

CONCLUSION

In 2009, a survey was done with over 900 attendees going there individual answers 27.1 were in support of the non-physicists point of view, which is dualism. Although the question was hard to answer, the belief of dualism is still appraised by people from this century.

So for instance, a property dualist might claim that a material thing like a brain can have both physical properties and mental properties, and that these two kinds of properties have very significant differences.

So according to property dualism there are different kinds of properties: there are physical properties which can be seen by the eye and there are mental properties which can’t be seen by the eye.

The definition of a property dualism is the belief that the brain can have physical and mental characteristics. The belief of the descartes is that the brain is mainly physical but they are substances in the brain that are mental and physical. Descartes’ philosophical inquiry resulted in his belief that the mind is a non-physical entity or a thing, which exists in outer space. This philosophy is called Substance dualism. They view the mind as a substance, considering it is an entity of its own capable of independent existence.

Category of positions in the philosophy of mind| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this article. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Property dualism" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Property dualism describes a category of positions in the philosophy of mind which hold that, although the world is composed of just one kind of substance—the physical kind—there exist two distinct kinds of properties: physical properties and mental properties. In other words, it is the view that non-physical, mental properties (such as thoughts, imagination and memories) exist in, or naturally supervene upon, certain physical substances (namely brains).

Substance dualism, on the other hand, is the view that there exist in the universe two fundamentally different kinds of substance: physical (matter) and non-physical (mind or consciousness), and subsequently also two kinds of properties which inhere in those respective substances. Substance dualism is thus more susceptible to the mind–body problem. Both substance and property dualism are opposed to reductive physicalism.

Non-reductive physicalism

Main article: Non-reductive physicalismNon-reductive physicalism is the predominant contemporary form of property dualism according to which mental properties are mapped to neurobiological properties, but are not reducible to them. Non-reductive physicalism asserts that mind is not ontologically reducible to matter, in that an ontological distinction lies in the differences between the properties of mind and matter. It asserts that while mental states are physical in that they are caused by physical states, they are not ontologically reducible to physical states. No mental state is the same one thing as some physical state, nor is any mental state composed merely from physical states and phenomena.

Emergent materialism

Main article: Emergent materialismEmergentism is the idea that increasingly complex structures in the world give rise to the "emergence" of novel properties that are something over and above (i.e. cannot be reduced to) their more basic constituents (see Supervenience). The concept of emergence dates back to the late 19th century. John Stuart Mill notably argued for an emergentist conception of science in his 1843 work A System of Logic.

Applied to the mind/body relation, emergent materialism is another way of describing the non-reductive physicalist conception of the mind that asserts that when matter is organized in the appropriate way (i.e., organized in the way that living human bodies are organized), mental properties emerge.

Anomalous monism

Main article: Anomalous monismMany contemporary non-reductive physicalists subscribe to a position called anomalous monism (or something very similar to it). Unlike epiphenomenalism, which renders mental properties causally redundant, anomalous monists believe that mental properties make a causal difference to the world. The position was originally put forward by Donald Davidson in his 1970 paper Mental Events, which stakes an identity claim between mental and physical tokens based on the notion of supervenience.

Biological naturalism

Main article: Biological naturalism

Another argument for non-reductive physicalism has been expressed by John Searle, who is the advocate of a distinctive form of physicalism he calls biological naturalism. His view is that although mental states are not ontologically reducible to physical states, they are causally reducible (see causality). He believes the mental will ultimately be explained through neuroscience. This worldview does not necessarily fall under property dualism, and therefore does not necessarily make him a "property dualist". He has acknowledged that "to many people" his views and those of property dualists look a lot alike. But he thinks the comparison is misleading.

Epiphenomenalism

Main article: EpiphenomenalismEpiphenomenalism is a doctrine about mental-physical causal relations which holds that one or more mental states and their properties are the by-products (or epiphenomena) of the states of a closed physical system, and are not causally reducible to physical states (do not have any influence on physical states). According to this view mental properties are as such real constituents of the world, but they are causally impotent; while physical causes give rise to mental properties like sensations, volition, ideas, etc., such mental phenomena themselves cause nothing further - they are causal dead ends.

The position is credited to English biologist Thomas Huxley (Huxley 1874), who analogised mental properties to the whistle on a steam locomotive. The position found favour amongst scientific behaviourists over the next few decades, until behaviourism itself fell to the cognitive revolution in the 1960s. Recently, epiphenomenalism has gained popularity with those struggling to reconcile non-reductive physicalism and mental causation.

Epiphenomenal qualia

Main article: Knowledge argumentIn the paper "Epiphenomenal Qualia" and later "What Mary Didn't Know" Frank Jackson made the so-called knowledge argument against physicalism. The thought experiment was originally proposed by Jackson as follows:

Mary is a brilliant scientist who is, for whatever reason, forced to investigate the world from a black and white room via a black and white television monitor. She specializes in the neurophysiology of vision and acquires, let us suppose, all the physical information there is to obtain about what goes on when we see ripe tomatoes, or the sky, and use terms like 'red', 'blue', and so on. She discovers, for example, just which wavelength combinations from the sky stimulate the retina, and exactly how this produces via the central nervous system the contraction of the vocal cords and expulsion of air from the lungs that results in the uttering of the sentence 'The sky is blue'. What will happen when Mary is released from her black and white room or is given a color television monitor? Will she learn anything or not?

Jackson continued:

It seems just obvious that she will learn something about the world and our visual experience of it. But then it is inescapable that her previous knowledge was incomplete. But she had all the physical information. Ergo there is more to have than that, and Physicalism is false.

Panpsychist property dualism

Main article: PanpsychismPanpsychism is the view that all matter has a mental aspect, or, alternatively, all objects have a unified center of experience or point of view. Superficially, it seems to be a form of property dualism, since it regards everything as having both mental and physical properties. However, some panpsychists say that mechanical behaviour is derived from the primitive mentality of atoms and molecules — as are sophisticated mentality and organic behaviour, the difference being attributed to the presence or absence of complex structure in a compound object. So long as the reduction of non-mental properties to mental ones is in place, panpsychism is not strictly a form of property dualism; otherwise it is.

David Chalmers has expressed sympathy for panpsychism (or a modified variant, panprotopsychism) as a possible resolution to the hard problem of consciousness, though he regards the combination problem as an important obstacle for the theory. Other philosophers who have taken interest in the view include Thomas Nagel, Galen Strawson, Timothy Sprigge, William Seager, and Philip Goff.

Other proponents

Saul Kripke

Kripke has a well-known argument for some kind of property dualism. Using the concept of rigid designators, he states that if dualism is logically possible, then it is the case.

Let 'Descartes' be a name, or rigid designator, of a certain person, and let 'B' be a rigid designator of his body. Then if Descartes were indeed identical to B, the supposed identity, being an identity between two rigid designators, would be necessary.

Subjective idealism

Subjective idealism, proposed in the eighteenth century by George Berkeley, is an ontic doctrine that directly opposes materialism or physicalism. It does not admit ontic property dualism, but does admit epistemic property dualism. It is rarely advocated by philosophers nowadays.

See also

- Physicalism

- Functionalism (philosophy of mind)

- Qualia

- "What Is It Like to Be a Bat?"

- Explanatory gap

- Chinese room

Notes

- Searle, John (1983) "Why I Am Not a Property Dualist", "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-12-10. Retrieved 2007-03-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). - Churchland 1984, p. 11

- ^ Jackson 1982, p. 130 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFJackson1982 (help)

- Chalmers, David J. (2003). "Consciousness and its Place in Nature" (PDF). In Stich, Stephen P.; Warfield, Ted A. (eds.). The Blackwell Guide to Philosophy of Mind (1st ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0631217756. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ Goff, Philip; Seager, William; Allen-Hermanson, Sean (2017). "Panpsychism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- Strawson, Galen (2006). "Realistic monism: Why physicalism entails panpsychism" (PDF). Journal of Consciousness Studies. 13 (10/11): 3–31. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- Seager, William (2006). "The Intrinsic Nature Argument for Panpsychism" (PDF). Journal of Consciousness Studies. 13 (10–11): 129–145. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- Goff, Philip (2017). "The Case for Panpsychism". Philosophy Now. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

References

- Churchland, Paul (1984). Matter and Consciousness.

- Davidson, D. (1970) "Mental Events", in Actions and Events, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980

- Huxley, Thomas. (1874) "On the Hypothesis that Animals are Automata, and its History", The Fortnightly Review, n.s. 16, pp. 555–580. Reprinted in Method and Results: Essays by Thomas H. Huxley (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1898)

- Jackson, F. (1982) "Epiphenomenal Qualia", The Philosophical Quarterly 32: 127-136.

- Kim, Jaegwon. (1993) "Supervenience and Mind", Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- MacLaughlin, B. (1992) "The Rise and Fall of British Emergentism", in Beckerman, et al. (eds), Emergence or Reduction?, Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Mill, John Stuart (1843). "System of Logic". London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer. .

External links

- M. D. Robertson: Dualism vs. Materialism: A Response to Paul Churchland

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Dualism

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Epiphenomenalism

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Physicalism

- The Argument from Physical Minds