This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Kline (talk | contribs) at 00:36, 1 April 2023 (verifying). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:36, 1 April 2023 by Kline (talk | contribs) (verifying)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Equine medication Pharmaceutical compound | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Rompun, Anased, Sedazine, Chanazine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, inhalation, or injection (intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous) |

| ATCvet code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

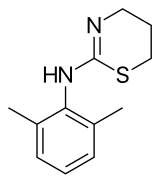

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.093 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H16N2S |

| Molar mass | 220.33 g·mol |

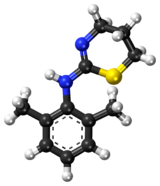

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (what is this?) (verify) | |

Xylazine is a pharmaceutical drug used for sedation, anesthesia, muscle relaxation, and analgesia in animals such as horses, cattle, and other non-human mammals. Veterinarians also use xylazine as an emetic, especially in cats. It is an analog of clonidine and an agonist at the α2 class of adrenergic receptor.

In veterinary anesthesia, xylazine is often used in combination with ketamine. It is sold under many brand names worldwide, most notably the Bayer brand name Rompun. It is also marketed as Anased, Sedazine, and Chanazine. The drug interactions vary with different animals.

Xylazine has become a drug of abuse in the United States, where it is known by the street name "tranq", and particularly in Puerto Rico. The drug is being diverted from stocks used by equine veterinarians and used as a cutting agent for heroin, causing skin sores and infections at injection sites, as well as other health issues.

History

Xylazine was discovered as an antihypertensive agent in 1962 by Farbenfabriken Bayer in Leverkusen, Germany. Results from early human clinical studies confirmed that xylazine has several central nervous system depressant effects. Xylazine administration is used for sedation, anesthesia, muscle relaxation, and analgesia. It causes a significant reduction in blood pressure and heart rate in healthy volunteers. Due to hazardous side effects, including hypotension and bradycardia, xylazine was not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for human use. As a result, xylazine's mechanism of action in humans remains unknown.

Xylazine was approved by the FDA for veterinary use and is now used as an animal tranquilizer. In the United States, xylazine was only approved by the FDA for veterinary use as a sedative, analgesic, and muscle relaxant in dogs, cats, horses, elk, fallow deer, mule deer, sika deer, and white-tailed deer. The sedative and analgesic effects of xylazine are related to central nervous system depression. Xylazine's muscle relaxant effect inhibits the transmission of neural impulses in the central nervous system.

In scientific research, xylazine is a component of the most common anesthetic, ketamine-xylazine (see rodent cocktail), which is used in rats, mice, hamster, and guinea pigs. The accounts of the actions and uses of xylazine in animals were reported as early as the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Medical uses

Xylazine is widely used in veterinary medicine as a sedative, muscle relaxant, and analgesic. It is frequently used in the treatment of tetanus. However it is rarely if ever used in human medical treatment. Xylazine is similar to drugs such as phenothiazine, tricyclic antidepressants, and clonidine. As an anesthetic, it is typically used in conjunction with ketamine.

Veterinary use

In animals, xylazine may be administered intramuscularly or intravenously. As a veterinary anesthetic, xylazine is typically only administered once for intended effect before or during surgical procedures. Alpha-2 antagonists such as atipamezole and yohimbine may be used to reverse the effects of xylazine in animals.

Side effects

Side effects in animals include transient hypertension, hypotension, and respiratory depression. Further, the decrease of tissue sensitivity to insulin leads to xylazine-induced hyperglycemia and a reduction of tissue glucose uptake and utilization. The duration of effects in animals lasts up to 4 hours.

Pharmacokinetics

In dogs, sheep, horses, and cattle, the half-life is very short: only 1.21–5.97 minutes. Complete elimination of the drug can take up to 23.11 minutes in sheep and up to 49.51 minutes in horses. In young rats, the half life is one hour. Xylazine has a large volume of distribution (Vd). The Vd = 1.9–2.5 for horses, cattle, sheep, and dogs. Though the peak plasma concentrations are reached in 12–14 minutes in all species, the bioavailability varies between species. The half life depends on the age of the animal, as age is related to prolonged duration of anesthesia and recovery time. Toxicity occurs with repeated administration, given that the metabolic clearance of the drug is usually calculated as 7–9 times the half-life, which is 4 to 5 days for the clearance of xylazine.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Xylazine is a potent α2 adrenergic agonist. When xylazine and other α2 adrenergic receptor agonists are administered, they distribute throughout the body within 30–40 minutes. Due to xylazine's highly lipophilic nature, xylazine directly stimulates central α2 receptors as well as peripheral α-adrenoceptors in a variety of tissues. As an agonist, xylazine leads to a decrease in neurotransmission of norepinephrine and dopamine in the central nervous system. It does so by mimicking norepinephrine in binding to presynaptic surface autoreceptors, which leads to feedback inhibition of norepinephrine.

Xylazine also serves as a transport inhibitor by suppressing norepinephrine transport function through competitive inhibition of substrate transport. Accordingly, xylazine significantly increases Km and does not affect Vmax. This likely occurs by direct interaction on an area that overlaps with the antidepressant binding site. For example, xylazine and clonidine suppress uptake of MIBG, a norepinephrine analog, in neuroblastoma cells. Xylazine has varying affinities for cholinergic, serotonergic, dopaminergic, α1 adrenergic, H2-histaminergic and opiate receptors. Its chemical structure closely resembles the phenothiazines, tricyclic antidepressants, and clonidine.

Pharmacokinetics in humans

Xylazine is absorbed, metabolized, and eliminated rapidly. Xylazine can be inhaled or administered intravenously, intramuscularly, subcutaneously, or orally either by itself or in conjunction with other anesthetics, such as ketamine, barbiturates, chloral hydrate, and halothane in order to provide reliable anesthesia effects. The most common route of administration is injection. The drug is used as a veterinary anesthetic and the recommended dose varies between species.

Xylazine's action can be seen usually 15–30 minutes after administration and the sedative effect may continue for 1–2 hours and last up to 4 hours. Once xylazine gains access to the vascular system, it is distributed within the blood, allowing xylazine to perfuse target organs including the heart, lungs, liver, and kidney. In nonfatal cases, the blood plasma concentrations range from 0.03–4.6 mg/L. Xylazine diffuses extensively and penetrates the blood–brain barrier, as might be expected due to the uncharged, lipophilic nature of the compound.

Xylazine is metabolized by liver cytochrome P450 enzymes. When it reaches the liver, xylazine is metabolized and proceeds to the kidneys to be excreted as urine. Around 70% of a dose is excreted by urine. Thus, urine can be used in detecting xylazine administration because it contains many metabolites, which are the main targets and products in urine. Within a few hours, xylazine decreases to undetectable levels. Other factors can also significantly impact the pharmacokinetics of xylazine, including sex, nutrition, environmental conditions, and prior diseases.

Xylazine Metabolites Xylazine-M (2,6 dimethylaniline) Xylazine-M (N-thiourea-2,6-dimethylaniline) Xylazine-M (sulfone-HO-) isomer 2 Xylazine-M (HO-2,6-dimethylaniline isomer 1) Xylazine-M (HO-2,6-dimethylaniline isomer 2) Xylazine M (oxo-) Xylazine-M (HO-) isomer 1 Xylazine-M (HO-) isomer 1 glucuronide Xylazine-M (HO-) isomer 2 Xylazine-M (HO-) isomer 2 glucuronide Xylazine-M (HO-oxo-) isomer 1 Xylazine-M (HO-oxo-) isomer 1 glucuronide Xylazine-M (HO-oxo-) isomer 2 Xylazine-M (HO-oxo-) isomer 2 glucuronide Xylazine-M (sulfone) Xylazine-M (sulfone-HO-) isomer 1

Recreational use

Since the early 2000s, xylazine has become popular as a drug of abuse in the United States and Puerto Rico. Xylazine's street name in Puerto Rico is anestesia de caballo, which translates to "horse anesthetic". Xylazine's street name in United States is "tranq", "tranq dope", and "zombie drug". While xylazine is almost invariably combined with opioids when used recreationally, it can produce a characteristic withdrawal syndrome in its own right which can complicate treatment of addicted users.

Xylazine users in Puerto Rico are more likely to be male, under age 30, living in a rural area, and injecting versus inhaling xylazine. Xylazine has similar behavioral consequences as heroin, thus it is commonly used as an adulterant. Xylazine is also frequently found in "speedball" (a mixture of several abused drugs – usually cocaine, heroin or morphine, and fentanyl). The combination of heroin and xylazine produces a potentially more deadly high than administration of heroin alone. Use of xylazine in combination with "speedball" may potentiate or prolong the effects of the other drugs, which can lead to adverse consequences.

In 1979, the first case of xylazine toxicity was reported, in a 34-year-old male who had self-medicated for insomnia with injection of 1 g of xylazine. Intentional intoxication from ingesting, inhaling, or injecting xylazine has been reported. The intravenous route is the most common route of administration for those who abuse heroin or xylazine recreationally. In Puerto Rico, xylazine has increased in popularity. Its use was associated with a high number of inmate deaths at the Guerrero Correctional Institution in Aguadilla, Puerto Rico, from 2002 to 2008.

When abused by humans, frequency of xylazine use depends on social or economic factors, as well as each user's subjective response to the drug's addictive properties. Naloxone can reverse the effect of opioid overdose, but has no effect on xylazine. As of November 2022, its detection in the bloodstream requires a spectrophotometer-based test.

Causal factors underlying xylazine's increasing popularity are still unknown. Further research is needed to gain more information on the distribution of xylazine in the body, physical symptoms, potential treatments, and factors predictive of chronic use.

Side effects

Xylazine overdose is often fatal in humans. Because it is used as a drug adulterant, the symptoms caused by the drugs accompanying xylazine administration vary between individuals.

The most common side effects in humans associated with xylazine administration include bradycardia, respiratory depression, hypotension, transient hypertension secondary to alpha-1 stimulation, and other central and hemodynamic changes. Xylazine significantly decreases heart rate in animals that are not premedicated with medications that have anticholinergic effects.

Xylazine administration can lead to diabetes mellitus and hyperglycemia. Other possible side effects that can occur are areflexia, asthenia, ataxia, blurred vision, disorientation, dizziness, drowsiness, dysarthria, dysmetria, fainting, hyporeflexia, slurred speech, somnolence, staggering, coma, apnea, shallow breathing, sleepiness, premature ventricular contraction, tachycardia, miosis, and dry mouth. Rarely, hypotonia, dry mouth, urinary incontinence and nonspecific electrocardiographic ST segment changes occur. It has been reported that the duration of symptoms after human overdose is 8–72 hours. Further research is necessary to categorize the side effects that occur when xylazine is used in conjunction with heroin and cocaine.

Chronic intravenous use of xylazine in combination with opioids is reported to be associated with physical deterioration, dependence, abscesses, and skin ulceration, sometimes progressing to necrosis with eschar formation, which can be physically debilitating and painful. Hypertension followed by hypotension, bradycardia, and respiratory depression lower tissue oxygenation in the skin. Thus, chronic use of xylazine can progress the skin oxygenation deficit, leading to severe skin ulceration. Lower skin oxygenation is associated with impaired healing of wounds and a higher chance of infection. The ulcers may ooze pus and have a characteristic odor. In severe cases, amputations must be performed on the affected extremities.

Overdose

The known doses of xylazine that produce toxicity and fatality in humans vary from 40 to 2400 mg. Small doses may produce toxicity and larger doses may be survived with medical assistance. Non-fatal blood or plasma concentration ranges from 0.03 to 4.6 mg/L. In fatalities, the blood concentration of xylazine ranges from trace to 16 mg/L. It is reported that there is no defined safe or fatal concentration of xylazine because of the significant overlap between the non-fatal and postmortem blood concentrations of xylazine.

Currently, there is no specific antidote to treat humans who overdose on xylazine. Hemodialysis has been suggested as a form of treatment, but is usually unfavorable due to the large volume of distribution of xylazine. In addition, due to lack of research in humans, there are no standardized screenings to determine if an overdose has occurred. The detection of xylazine in biological fluids in humans involves various screening methods, such as urine screenings, thin layer chromatography (TLC), gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS). In veterinary medicine, the alpha-2 antagonist atipamezole is used to reverse the effects of xylazine or the related drug dexmedetomidine, but while this has been tested in humans in Phase I trials, it is not an approved medical treatment for xylazine overdose.

Multiple drugs have been used as supportive therapeutic intervention such as lidocaine, naloxone, thiamine, lorazepam, vecuronium, etomidate, propofol, tolazoline, yohimbine, atropine, orciprenaline, metoclopramide, ranitidine, metoprolol, enoxaparin, flucloxacillin, insulin, and irrigation of both eyes with saline. Effects of xylazine are also reversed by the analeptics 4-aminopyridine, doxapram, and caffeine, which are physiological antagonists to central nervous system depressants. Research initiatives may be necessary in order to standardize treatment and determine effective measures for identifying chronic xylazine usage and intoxication.

The treatment after xylazine overdose should primarily involve maintaining respiratory function and blood pressure. In cases of intoxication, physicians recommend intravenous fluid infusion, atropine, and hospital observation. Severe cases may require endotracheal intubation, mechanical ventilation, gastric lavage, activated charcoal, bladder catheterization, electrocardiographic (ECG) and hyperglycemia monitoring. Physicians typically recommend which detoxification treatment should be used to manage possible dysfunction involving highly perfused organs, such as the liver and kidney.

References

- ^ "Xylazine". techynewsblogs.com.

- Dowling PM (June 2016) . "Drugs to control or stimulate vomiting (monogastric)". Merck Veterinary Manual (professional ed.). Rahway, NJ: Merck & Co.

- ^ Greene SA, Thurmon JC (December 1988). "Xylazine—a review of its pharmacology and use in veterinary medicine". Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 11 (4): 295–313. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2885.1988.tb00189.x. PMID 3062194.

- ^ Ruiz-Colón K, Chavez-Arias C, Díaz-Alcalá JE, Martínez MA (July 2014). "Xylazine intoxication in humans and its importance as an emerging adulterant in abused drugs: A comprehensive review of the literature". Forensic Science International. 240: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.03.015. PMID 24769343.

- Haskins SC, Patz JD, Farver TB (March 1986). "Xylazine and xylazine-ketamine in dogs". American Journal of Veterinary Research. 47 (3): 636–641. PMID 3963565.

- Muir WW, Skarda RT, Milne DW (February 1977). "Evaluation of xylazine and ketamine hydrochloride for anesthesia in horses". American Journal of Veterinary Research. 38 (2): 195–201. PMID 842917.

- Aithal HP, Pratap AK, Singh GR (1997). "Clinical effects of epidurally administered ketamine and xylazine in goats". Small Ruminant Research. 24 (1): 55–64. doi:10.1016/s0921-4488(96)00919-4.

- ^ Torruella RA (April 2011). "Xylazine (veterinary sedative) use in Puerto Rico". Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 6: 7. doi:10.1186/1747-597x-6-7. PMC 3080818. PMID 21481268.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Reyes JC, Negrón JL, Colón HM, Padilla AM, Millán MY, Matos TD, Robles RR (June 2012). "The emerging of xylazine as a new drug of abuse and its health consequences among drug users in Puerto Rico". Journal of Urban Health. 89 (3): 519–526. doi:10.1007/s11524-011-9662-6. PMC 3368046. PMID 22391983.

- ^ Xiao YF, Wang B, Wang X, Du F, Benzinou M, Wang YX (October 2013). "Xylazine-induced reduction of tissue sensitivity to insulin leads to acute hyperglycemia in diabetic and normoglycemic monkeys". BMC Anesthesiology. 13 (1): 33. doi:10.1186/1471-2253-13-33. PMC 4016475. PMID 24138083.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Delehant TM, Denhart JW, Lloyd WE, Powell JD (2003). "Pharmacokinetics of xylazine, 2,6-dimethylaniline, and tolazoline in tissues from yearling cattle and milk from mature dairy cows after sedation with xylazine hydrochloride and reversal with tolazoline hydrochloride". Veterinary Therapeutics. 4 (2): 128–134. PMID 14506588.

- ^ Veilleux-Lemieux D, Castel A, Carrier D, Beaudry F, Vachon P (September 2013). "Pharmacokinetics of ketamine and xylazine in young and old Sprague-Dawley rats". Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science. 52 (5): 567–570. PMC 3784662. PMID 24041212.

- Kollias-Baker CA, Court MH, Williams LL. Influence of yohimbine and tolazoline on the cardiovascular, respiratory, and sedative effects of xylazine in the horse. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 1993 Sep;16(3):350-8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2885.1993.tb00182.x PMID 8230406

- Murahata Y, Miki Y, Hikasa Y. Antagonistic effects of atipamezole, yohimbine, and prazosin on xylazine-induced diuresis in clinically normal cats. Can J Vet Res. 2014 Oct;78(4):304-15. PMID 25356000

- Janssen CF, Maiello P, Wright MJ Jr, Kracinovsky KB, Newsome JT. Comparison of Atipamezole with Yohimbine for Antagonism of Xylazine in Mice Anesthetized with Ketamine and Xylazine. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2017 Mar 1;56(2):142-147. PMID 28315642

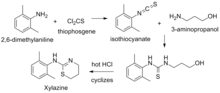

- US expired 4614798A, Elliott, Richard L. & Ruehle, Paul H., "Process for the production of xylazine", issued 30 September 1986, assigned to Vetamix (expired 9 April 2005).

- ^ Park JW, Chung HW, Lee EJ, Jung KH, Paik JY, Lee KH (April 2013). "α2-Adrenergic agonists including xylazine and dexmedetomidine inhibit norepinephrine transporter function in SK-N-SH cells". Neuroscience Letters. 541: 184–189. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2013.02.022. PMID 23485735. S2CID 46338840.

- ^ Silva-Torres L, Veléz C, Alvarez L, Zayas B (2014). "Xylazine as a drug of abuse and its effects on the generation of reactive species and DNA damage on human umbilical vein endothelial cells". Journal of Toxicology. 2014: 492609. doi:10.1155/2014/492609. PMC 4243599. PMID 25435874.

- Barroso M, Gallardo E, Margalho C, Devesa N, Pimentel J, Vieira DN (April 2007). "Solid-phase extraction and gas chromatographic–mass spectrometric determination of the veterinary drug xylazine in human blood". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 31 (3): 165–169. doi:10.1093/jat/31.3.165. PMID 17579964.

- ^ Meyer GM, Maurer HH (December 2013). "Qualitative metabolism assessment and toxicological detection of xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer and drug of abuse, in rat and human urine using GC-MS, LC-MSn, and LC-HR-MSn". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 405 (30): 9779–9789. doi:10.1007/s00216-013-7419-7. PMID 24141317. S2CID 23164588.

- "Opioid Epidemic Updates: "Frankenstein Opioids" and Xylazine-Induced Skin Ulcers". aafp.org. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- Johnson J, Pizzicato L, Johnson C, Viner K (August 2021). "Increasing presence of xylazine in heroin and/or fentanyl deaths, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2010-2019". Injury Prevention. 27 (4): 395–398. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2020-043968. PMID 33536231.

- ^ Hoffman J (7 January 2023). "Tranq Dope: Animal Sedative Mixed With Fentanyl Brings Fresh Horror to U.S. Drug Zones". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- Friedman J, Montero F, Bourgois P, Wahbi R, Dye D, Goodman-Meza D, Shover C. Xylazine spreads across the US: A growing component of the increasingly synthetic and polysubstance overdose crisis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022 Apr 1;233:109380. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109380 PMID 35247724

- Ehrman-Dupre R, Kaigh C, Salzman M, Haroz R, Peterson LK, Schmidt R. Management of Xylazine Withdrawal in a Hospitalized Patient: A Case Report. J Addict Med. 2022 Sep-Oct 01;16(5):595-598. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000955 PMID 35020700

- Carruthers SG, Nelson M, Wexler HR, Stiller CR (October 1979). "Xylazine hydrochloridine (Rompun) overdose in man". Clinical Toxicology. 15 (3): 281–285. doi:10.3109/15563657908989878. PMID 509891.

- "Research Topics - Xylazine". National Institute on Drug Abuse. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- "Xylazine Public Health Advisory, November 2022" (PDF). Boston Public Health Commission. City of Boston. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- Ball NS, Knable BM, Relich TA, Smathers AN, Gionfriddo MR, Nemecek BD, Montepara CA, Guarascio AJ, Covvey JR, Zimmerman DE. Xylazine poisoning: a systematic review. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2022 Aug;60(8):892-901. doi:10.1080/15563650.2022.2063135 PMID 35442125

- Scheinin H, Aantaa R, Anttila M, Hakola P, Helminen A, Karhuvaara S. Reversal of the sedative and sympatholytic effects of dexmedetomidine with a specific alpha2-adrenoceptor antagonist atipamezole: a pharmacodynamic and kinetic study in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology. 1998 Sep;89(3):574-84. doi:10.1097/00000542-199809000-00005 PMID 9743392

- Pertovaara A, Haapalinna A, Sirviö J, Virtanen R. Pharmacological properties, central nervous system effects, and potential therapeutic applications of atipamezole, a selective alpha2-adrenoceptor antagonist. CNS Drug Rev. 2005 Autumn;11(3):273-88. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2005.tb00047.x PMID 16389294

- Ndeereh DR, Mbithi PM, Kihurani DO (June 2001). "The reversal of xylazine hydrochloride by yohimbine and 4-aminopyridine in goats". Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 72 (2): 64–67. doi:10.4102/jsava.v72i2.618. PMID 11513261.

Further reading

- McCurnin DM, Bassert JM (2002). Clinical Textbook for Veterinary Technicians (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders.

- "Rompun Homepage". Bayer Healthcare. 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-03-02.

- Wright B (2000). "Human health concerns when working with medications around horses". Agdex# 460. Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA).

| Adrenergic receptor modulators | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 |

| ||||

| α2 |

| ||||

| β |

| ||||