This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Iwao24 (talk | contribs) at 23:01, 23 June 2023 (Too many wishes and unfounded hopes Too much use of "probably" See discussion for details). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 23:01, 23 June 2023 by Iwao24 (talk | contribs) (Too many wishes and unfounded hopes Too much use of "probably" See discussion for details)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article is missing information about Contemporary influence. Please expand the article to include this information. Further details may exist on the talk page. (February 2023) |

Korean influence on Japanese culture refers to the impact of continental Asian influences transmitted through or originating in the Korean Peninsula on Japanese institutions, culture, language and society. Since the Korean Peninsula was the cultural bridge between Japan and China throughout much of East Asian history, these influences have been detected in a variety of aspects of Japanese culture, including technology, philosophy, art, and artistic techniques.

Notable examples of Korean influence on Japanese culture include the prehistoric migration of Korean peninsular peoples to Japan near the end of Japan's Jōmon period and the introduction of Buddhism to Japan via the Kingdom of Baekje in 538 AD. From the mid-fifth to the late-seventh centuries, Japan benefited from the immigration of people from Baekje and Gaya who brought with them their knowledge of iron metallurgy, stoneware pottery, law, and Chinese writing. These people were known as Toraijin. The modulation of continental styles of art in Korea has also been discerned in Japanese painting and architecture, ranging from the design of Buddhist temples to smaller objects such as statues, textiles and ceramics. Late in the sixteenth century, the Japanese invasions of Korea produced considerable cross-cultural contact. Korean craftsmen who came to Japan at this time were responsible for a revolution in Japanese pottery making.

Many Korean influences on Japan originated in China, but were adapted and modified in Korea before reaching Japan. The role of ancient Korean states in the transmission of continental civilization has long been neglected, and is increasingly the object of academic study. However, Korean and Japanese nationalisms have complicated the interpretation of these influences.

Lacquerwork

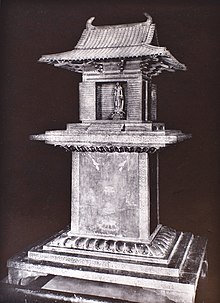

According to the historian Beatrix von Ragué, "the oldest example of the true art of lacquerwork to have survived in Japan" is Tamamushi Shrine, a miniature shrine in Horyū-ji Temple. Tamamushi Shrine was created in Korean style, and was probably made by either a Japanese artist or a Korean artist living in Japan. It is decorated with an inlay composed of the wings of tamamushi beetles that, according to von Ragué, "is evidently native to Korea." However, Tamamushi Shrine is also painted in a manner similar to Chinese paintings of the sixth century.

Japanese lacquerware teabowls, boxes, and tables of the Azuchi–Momoyama period (1568–1600) also show signs of Korean artistic influence. The mother-of-pearl inlay frequently used in this lacquerwork is of clearly Korean origin.

Painting

The immigration of Korean and Chinese painters to Japan during the Asuka period transformed Japanese art. For instance, in the year 610 Damjing, a Buddhist monk from Goguryeo, brought paints, brushes, and paper to Japan. Damjing is credited with introducing the arts of papermaking and of preparing pigments to Japan for the first time, and he is also regarded as the artist behind the wall painting in the main hall of Japan's Horyu-ji Temple which was later burned down in a fire.

However, it was during the Muromachi period (1337–1573) of Japanese history that Korean influence on Japanese painting reached its peak. Korean art and artists frequently arrived on Japan's shores, influencing both the style and theme of Japanese ink painting. The two most important Japanese ink painters of the period were Shūbun, whose art displays many of the characteristic features of Korean painting, and Sumon, who was himself an immigrant from Korea. Consequently, one Japanese historian, Sokuro Wakimoto, has even described the period between 1394 and 1486 as the "Era of Korean Style" in Japanese ink painting.

Then during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as a result of the Joseon missions to Japan, the Japanese artists who were developing nanga painting came into close contact with Korean artists. Though Japanese nanga received inspiration from many sources, the historian Burglind Jungmann concludes that Korean namjonghwa painting "may well have been the most important for creating the Nanga style". It was the Korean brush and ink techniques in particular which are known to have had a significant impact on such Japanese painters as Ike no Taiga, Gion Nankai, and Sakaki Hyakusen.

Music and dance

In ancient times the imperial court of Japan imported all its music from abroad, though it was Korean music that reached Japan first. The first Korean music may have infiltrated Japan as early as the third century. Korean court music in ancient Japan was at first called "sankangaku" in Japanese, referring to music from all the states of the Korean peninsula, but it was later termed "komagaku" in reference specifically to the court music of the Korean kingdom of Guguryeo.

Musicians from various Korean states often went to work in Japan. Mimaji, a Korean entertainer from Baekje, introduced Chinese dance and Chinese gigaku music to Japan in 612. By the time of the Nara period (710–794), every musician in Japan's imperial court was either Korean or Chinese. Korean musical instruments which became popular in Japan during this period include the flute known as the komabue, the zither known as the gayageum, and the harp known as the shiragikoto.

Though much has been written about Korean influence on early Japanese court music, Taeko Kusano has stated that Korean influence on Japanese folk music during the Edo period (1603–1868) represents a very important but neglected field of study. According to Taeko Kusano, each of the Joseon missions to Japan included about fifty Korean musicians and left their mark on Japanese folk music. Most notably, the "tojin procession", which was practiced in Nagasaki, the "tojin dance", which arose in modern-day Mie Prefecture, and the "karako dance", which exists in modern-day Okayama Prefecture, all have Korean roots and utilize Korean-based music.

Silk weaving

Further information: SericultureAccording to William Wayne Farris, citing a leading Japanese expert on ancient cloth, the production of high-quality silk twill took off in Japan from the fifth century onward as a result of new technology brought from Korea. Farris argues that Japan's Hata clan, who are believed to have been specialists in the art of silk weaving and silk tapestry, immigrated to Japan from the region of the Korean peninsula. By contrast, historian Cho-yun Hsu believes that the Hata clan were of Chinese descent.

Jewelry

Japan at first imported jewelry made of glass, gold, and silver from Korea, but in the fifth century the techniques of gold and silver metallurgy also entered Japan from Korea, possibly from the Korean states of Baekje and Gaya. Korean immigrants established important sites of jewelry manufacturing in Katsuragi, Gunma, and other places in Japan, allowing Japan to domestically produce its first gold and silver earrings, crowns, and beads.

Sculpture

Along with Buddhism, the art of Buddhist sculpture also spread to Japan from Korea. At first almost all Japanese Buddhist sculptures were imported from Korea, and these imports demonstrate an artistic style which would dominate Japanese sculpture during the Asuka period (538–710). In the years 577 and 588 the Korean state of Baekje dispatched to Japan expert statue sculptors.

One of the most notable examples of Korean influence on Japanese sculpture is the Buddha statue in the Koryu-ji Temple, sometimes referred to as the "Crown-Coiffed Maitreya". This statue was directly copied from a Korean prototype around the seventh century. Likewise, the Great Buddha sculpture of Todai-ji Temple, as well as both the Baekje Kannon and the Guze Kannon sculptures of Japan's Horyu-ji Temple, are believed to have been sculpted by Koreans. The Guze Kannon was described as "the greatest perfect monument of Corean art" by Ernest Fenollosa.

Literature

Concerning literature, Roy Andrew Miller has stated that, "Japanese scholars have made important progress in identifying the seminal contributions of Korean immigrants, and of Korean literary culture as brought to Japan by the early Korean diaspora from the Old Korean kingdoms, to the formative stages of early Japanese poetic art". Susumu Nakanishi has argued that Okura was born in the Korean kingdom of Baekje to a high court doctor and came with his émigré family to Yamato at the age of 3 after the collapse of that kingdom. It has been noted that the Korean genre of hyangga (郷歌), of which only 25 examples survive from the Silla kingdom's Samdaemok (三代目), compiled in 888 CE, differ greatly in both form and theme from the Man'yōshū poems, with the single exception of some of Yamanoue no Okura's poetry which shares their Buddhist-philosophical thematics. Roy Andrew Miller, arguing that Okura's "Korean ethnicity" is an established fact though one disliked by the Japanese literary establishment, speaks of his "unique binational background and multilingual heritage".

Architecture

William Wayne Farris has noted that "Architecture was one art that changed forever with the importation of Buddhism" from Korea. In 587 the Buddhist Soga clan took control of the Japanese government, and the very next year in 588 the kingdom of Baekje sent Japan two architects, one carpenter, four roof tilers, and one painter who were assigned the task of constructing Japan's first full-fledged Buddhist temple. This temple was Asuka Temple, completed in 596, and it was only the first of many such temples put together on the Baekje model. According to the historian Jonathan W. Best "virtually all of the numerous complete temples built in Japan between the last decade of the sixth and the middle of the seventh centuries" were designed off Korean models. Among such early Japanese temples designed and built with Korean aid are Shitennō-ji Temple and Hōryū-ji Temple.

Many of the temple bells were also of Korean design and origin. As late as the early eleventh century Korean bells were being delivered to many Japanese temples including Enjō-ji Temple. In the year 1921, eighteen Korean temple bells were designated as national treasures of Japan.

In addition to temples, starting from the sixth century advanced stonecutting technology entered Japan from Korea and as a result Japanese tomb construction also began to change in favor of Korean models. Around this time the horizontal tomb chambers prevalent in Baekje began to be constructed in Japan.

Cultural transfers during Hideyoshi's invasions of Korea

The invasions of Korea by Japanese leader Toyotomi Hideyoshi between 1592 and 1598 were an extremely vigorous period of two-way cross-cultural transfer between Korea and Japan. Although Japan ultimately lost the war, Hideyoshi and his generals used the opportunity to loot valuable commodities from Korea and to kidnap skilled Korean craftsmen and take them back to Japan. Tokutomi Sohō summed up the conflict by saying that, "While neither Japan nor Choson gained any advantages from this war, Japan gained cultural benefits from the importation of moveable type printing, technological benefits from ceramics, and diplomatic benefits from its contact with Ming China."

Printing technology and books

Moveable type printing was invented in China in the eleventh century, and the technology was further refined in Korea. According to the historian Lawrence Marceau, during the late-sixteenth century, dramatic changes in Japanese printing technology were sparked by "two overseas sources". The first was the movable type printing-press established by the Jesuits in Kyushu in 1590. The second was the looting of Korean books and book printing technology after the invasion of Korea. Before 1590, Buddhist monasteries handled virtually all book printing in Japan, and, according to historian Donald Shively, books and moveable type transported from Korea "helped bring about the end of the monastic monopoly on printing." At the start of the invasion in 1592, Korean books and book printing technology were one of Japan's top priorities for looting, especially metal moveable type. One commander alone, Ukita Hideie, is said to have had 200,000 printing types and books removed from Korea's Gyeongbokgung Palace. In 1593, a Korean printing press with movable type was sent as a present for the Japanese Emperor Go-Yōzei. The emperor commanded that it be used to print an edition of the Confucian Classic of Filial Piety. Four years later in 1597, apparently due to difficulties encountered in casting metal, a Japanese version of the Korean printing press was built with wooden instead of metal type. In 1599, this press was used to print the first part of the Nihon Shoki. Eighty percent of Japan's book production was printed using moveable type between 1593 and 1625, but ultimately moveable type printing was supplanted by woodblock printing and was rarely used after 1650.

Ceramics

Prior to the invasion, Korea's high-quality ceramic pottery was prized in Japan, particularly the Korean teabowls used in the Japanese tea ceremony. Because of this, Japanese soldiers made great efforts to find skilled Korean potters and transfer them to Japan. For this reason, the Japanese invasion of Korea is sometimes referred to as the "Teabowl War" or the "Pottery War".

Hundreds of Korean potters were taken by the Japanese Army back to Japan with them, either being forcibly kidnapped or else being persuaded to leave. Once settled in Japan, the Korean potters were put to work making ceramics. Historian Andrew Maske has concluded that, "Without a doubt the single most important development in Japanese ceramics in the past five hundred years was the importation of Korean ceramic technology as a result of the invasions of Korea by the Japanese under Toyotomi Hideyoshi." Imari porcelain, Satsuma ware, Hagi ware, Karatsu ware, and Takatori ware were all pioneered by Koreans who came to Japan at this time.

Construction

Among the skilled craftsmen removed from Korea by Japanese forces were roof tilers, who would go on to make important contributions to tiling Japanese houses and castles. For example, one Korean tiler participated in the expansion of Kumamoto Castle. Furthermore, the Japanese daimyo Katō Kiyomasa had Nagoya Castle constructed using stonework techniques that he had learned during his time in Korea.

Neo-Confucianism

Kang Hang, a Korean neo-Confucian scholar, was kidnapped in Korea by Japanese soldiers and taken to Japan. He lived in Japan until the year 1600 during which time he formed an acquaintance with the scholar Fujiwara Seika and instructed him in neo-Confucian philosophy. Some historians believe that other Korean neo-Confucianists such as Yi Toe-gye also had a major impact on Japanese neo-Confucianism at this time. The idea was developed in particular by Abe Yoshio (阿部吉雄).

By contrast, Willem van Boot called this theory in question in his 1982 doctoral thesis and later works. Historian Jurgis Elisonas stated the following about the controversy:

"A similar great transformation in Japanese intellectual history has also been traced to Korean sources, for it has been asserted that the vogue for neo-Confucianism, a school of thought that would remain prominent throughout the Edo period (1600–1868), arose in Japan as a result of the Korean war, whether on account of the putative influence that the captive scholar-official Kang Hang exerted on Fujiwara Seika (1561–1619), the soi-disant discoverer of the true Confucian tradition for Japan, or because Korean books from looted libraries provided the new pattern and much new matter for a redefinition of Confucianism. This assertion, however is questionable and indeed has been rebutted convincingly in recent Western scholarship."

Contemporary cultural influence

Yakiniku is seen as having a Korean origin and became popular in the 20th century.

While traditionally Japan has been seen as more of an influence on Korean pop culture and as having laid the foundations of kpop, the rise and success of kpop has increasingly come back to influence jpop in many ways such as choreography.

See also

- Japanese influence on Korean culture

- Chinese influence on Korean culture

- Chinese influence on Japanese culture

- Culture of Japan

- Culture of Korea

Notes

- Cartwright, Mark (November 25, 2016). "Ancient Korean & Japanese Relations". World History Encyclopedia.

- 渡来人. www.asuka-tobira.com (in Japanese). Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- 第2版,世界大百科事典内言及, 日本大百科全書(ニッポニカ),ブリタニカ国際大百科事典 小項目事典,旺文社日本史事典 三訂版,百科事典マイペディア,デジタル大辞泉,精選版 日本国語大辞典,世界大百科事典. "渡来人(とらいじん)とは? 意味や使い方". コトバンク (in Japanese). Retrieved 2023-02-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ von Ragué, pp. 5–7.

- von Ragué, pp. 176–179.

- ^ Akiyama, pp. 19–20, 26.

- ^ Lee (October 1970), pp. 18, 33.

- Needham and Tsien, p. 331.

- Needham and Wang, p. 401.

- Pak, p. 41.

- Ahn, pp. 195–201.

- Jungmann, pp. 205–211.

- ^ Malm, pp. 33, 98–100, 109.

- Banham, p. 559.

- ^ Lee (August 1970), pp. 12, 29.

- Kusano, pp. 31–36.

- ^ (Farris 1998, p. 97)

- Hsu, p. 248.

- (Farris 1998, pp. 96, 118)

- Rhee, Aikens, Choi, and Ro, pp. 441, 443.

- ^ McCallum (1982), pp. 22, 26, 28.

- (Farris 1998, pp. 102–103)

- ^ Jung, pp. 113–114, 119.

- Pak, pp. 42–45.

- McBride, 90.

- ^ Fenollosa, pp. 49–50.

- Portal, 52.

- Miller (1980), p. 776.

- Lee and Ramsey, pp. 2, 84: "Simplified kugyŏl looks like the Japanese katakana. Some of the resemblances are superficial ... ut many other symbols are identical in form and value ... We do not know just what the historical connections were between these two transcription systems. The origins of kugyŏl have still not been accurately dated or documented. But many in Japan as well as Korea believe that the beginnings of katakana and the orthographic principles they represent, derive at least in part from earlier practices on the Korean peninsular."

- Levy, pp.42–43.

- Miller (1997), pp. 85–86, p.104.

- ^ (Farris 1998, p. 103)

- Inoue, pp. 170–172.

- Mori Ikuo, p. 356.

- Korean Buddhist Research Institute, p. 52.

- Best, pp. 31–34.

- Lee (September 1970), pp. 20, 31.

- Farris, pp. 92–93.

- Pratt and Rutt, 190.

- Ha, p. 335.

- ^ Keene, p. 3.

- Marceau, p. 120.

- ^ Shively, p. 726.

- Ha, pp. 328–329.

- Portal, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Ha, pp. 330–331.

- ^ Maske, p. 43.

- ^ Koo Tae-hoon (2008). "Flowering of Korean Ceramic Culture in Japan". Korea Focus.

- ^ Ha, pp. 324–325.

- Chung, p. 22.

- Jansen, p. 70.

- Sato, p. 293.

- Tucker, p. 68.

- Lewis, p. 252.

- Elisonas, p. 293.

- Modern Japanese cuisine: food, power and national identity, Katarzyna Joanna Cwiertka

- Lie, John (2001). Multiethnic Japan. Harvard University Press, 77 ISBN 0-674-01358-1

- japan-guide.com "Yakiniku-ya specialize in Korean style barbecue, where small pieces of meat are cooked on a grill at the table. Other popular Korean dishes such as bibimba are also usually available at a yakiniku-ya."

- Chantal Garcia Japanese BBQ a best kept L.A. secret, Daily Trojan, 11/10/04

- Noelle Chun Yakiniku lets you cook and choose, The Honolulu Advertiser, August 20, 2004

- Yakiniku and Bulgogi: Japanese, Korean, and Global Foodways 中國飲食文化 Vol.6 No.2 (2010/07)

- "Why The Blueprint For K-Pop Actually Came From Japan". NPR. 8 January 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- "Netizens see K-pop's influence on J-pop as more Japanese idols benchmark K-pop idol content on YouTube". allkpop. Retrieved 2023-02-10.

Bibliography

- Ahn Hwi-Joon, "Korean Influence on Japanese Ink Paintings of the Muromachi Period", Korea Journal, Winter 1997.

- Akiyama, Terukazu, Japanese Painting. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1977.

- Banham, Martin, The Cambridge Guide to World Theatre. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Barnes, Gina, State Formation in Japan: Emergence of a 4th-Century Ruling Elite. New York: Routledge, 2007.

- Barnes, Gina, Archaeology of East Asia: The Rise of Civilization in China, Korea and Japan. Philadelphia: Oxbow Books, 2015.

- Batten, Bruce, Gateway to Japan: Hakata in War And Peace, 500–1300. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2006.

- Bentley, John R., A Descriptive Grammar of Early Old Japanese Prose. Boston: BRILL, 2001.

- Best, Jonathan W., "Paekche and the Incipiency of Buddhism in Japan", in Currents and Countercurrents: Korean Influences on the East Asian Buddhist Traditions, ed. Robert Buswell. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2005.

- Bowman, John, Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000.

- Buswell Jr., Robert, "Patterns of Influence in East Asian Buddhism: The Korean Case", in Currents and Countercurrents: Korean Influences on the East Asian Buddhist Traditions, ed. Robert Buswell. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2005.

- Chung, Edward, The Korean Neo-Confucianism of Yi T'oegye and Yi Yulgok. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995.

- Cho, Insoo, "Painters as Envoys: Korean Inspiration in Eighteenth Century Japanese Nanga (Review)", Journal of Korean Studies, Fall 2007.

- Cho, Youngjoo, "The Small but Magnificent Counter-Piracy Operations of the republic of Korea", in Freedom of Navigation and Globalization, eds. Myron H. Nordquist, John Norton Moore, Robert Beckman, and Ronan Long. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff Publishers, 2014.

- Ch'on Kwan-u, "A New Interpretation of the Problems of Mimana (I)". Korea Journal, February 1974.

- Como, Michael, Shotoku: Ethnicity, Ritual, and Violence in the Japanese Buddhist Tradition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Como, Michael, "Weaving and Binding: Immigrant Gods and Female Immortals in Ancient Japan". Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2009

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley and Walthall, Anne, East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Cengage Learning, 2013.

- Elisonas, Jurgis, "The Inseparable Trinity: Japan's Relations with China and Korea", in The Cambridge History of Japan Volume Four, ed. John Whitney Hall. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Em, Henry, The Great Enterprise: Sovereignty and Historiography in Modern Korea, Part 2. London: Duke University Press, 2013.

- Farris, William Wayne (1998). Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824820305.

- Farris, William Wayne, Japan to 1600: A Social and Economic History. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009.

- Fenollosa, Ernest, Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art Volume One. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1912.

- Frellesvig, Bjarke, A History of the Japanese Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Grayson, James H., Korea – A Religious History. New York: Routledge, 2013.

- Ha Woo Bong, "War and Cultural Exchange", in The East Asian War, 1592–1598, eds. James B. Lewis. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Habu, Junko, Ancient Jomon of Japan. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Hane, Mikiso, Premodern Japan: A Historical Survey. Boulder: Westview Press, 1991.

- Henshall, Kenneth G, A History of Japan: From Stone Age to Superpower. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999.

- Hsu, Cho-yun, China: A New Cultural History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

- Inoue Mitsusada, "The Century of Reform", in The Cambridge History of Japan Volume One, ed. Delmer M. Brown. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Jansen, Marius, The Making of Modern Japan. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 2000.

- Jung Hyoun, "Who Made Japan's National Treasure No. 1", in The Foreseen and the Unforeseen in Historical Relations Between Korea and Japan, eds. Northeast Asian History Foundation. Seoul: Northeast Asian History Foundation, 2009.

- Jungmann, Burglind, Painters as Envoys: Korean Inspiration in Eighteenth-Century Japanese Nanga. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Kamada Motokazu, "王権をめぐる戦い", in 大君による国土の統一, ed. Toshio Kishi. Tokyo: Chuo Koronsha, 1988.

- Kamata Shigeo, "The Transmission of Paekche Buddhism to Japan", in Introduction of Buddhism to Japan: New Cultural Patterns, eds. Lewis R. Lancaster and CS Yu. Berkeley, California: Asian Humanities Press, 1989.

- Kamstra, Jacques H., Encounter Or Syncretism: The Initial Growth of Japanese Buddhism. Leiden: Brill, 1967.

- Keene, Donald, World Within Walls: Japanese Literature of the Pre-Modern Era, 1600-1867 Volume One. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976.

- Keller, Agathe, and Volkov, Alexei, "Mathematics Education in Oriental Antiquity and Medieval Ages", in Handbook on the History of Mathematics Education, eds. Alexander Karp and Gert Schubring. New York: Springer, 2014.

- Kim, Eun Mee and Ryoo, Jiwon, "South Korean Culture Goes Global: K-Pop and the Korean Wave," Korean Social Science Journal, 2007.

- Kim, Jinwung, A History of Korea: From 'Land of the Morning Calm' to States in Conflict. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012.

- Korean Buddhist Research Institute, The History and Culture of Buddhism in Korea. Seoul, Korea: Dongguk University Press, 1993.

- Kusano, Taeko, "Unknown Aspects of Korean Influence on Japanese Folk Music", Yearbook for Traditional Music, 1983.

- Lee, Hyoun-jun, "Korean Influence on Japanese Culture (1)", Korean Frontier, August 1970.

- Lee, Hyoun-jun, "Korean Influence on Japanese Culture (2)", Korean Frontier, September 1970.

- Lee, Hyoun-jun, "Korean Influence on Japanese Culture (3)", Korean Frontier, October 1970.

- Lee, Ki-Moon, and Ramsey, S. Robert, A History of the Korean Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Levy, Ian Hideo, Hitomaro and the Birth of Japanese Lyricism. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Lewis, James B., Frontier Contact Between Choson Korea and Tokugawa Japan. New York: Routledge, 2005.

- Lu, Gwei-djen, and Needham, Joseph, Celestial Lancets: A History and Rationale of Acupuncture and Moxa. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

- Malm, William P., Traditional Japanese Music and Musical Instruments. New York: Kodansha International, 1959.

- Marceau, Lawrence, "Cultural Developments in Tokugawa Japan", in A Companion to Japanese History, ed. William M. Tsutsui. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

- Maske, Andrew, "The Continental Origins of Takatori Ware: The Introduction of Korean Potters and Technology to Japan Through the Invasions of 1592–1598", Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, 1994.

- McBride, Richard D., Domesticating the Dharma: Buddhist Cults and the Hwaom Synthesis in Silla Korea. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

- McCallum, Donald, "Korean Influence on Early Japanese Buddhist Sculpture," Korean Culture, March 1982.

- McCallum, Donald, The Four Great Temples: Buddhist Archaeology, Architecture, and Icons of Seventh-Century Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009.

- Miller, Roy Andrew, "Uri Famëba", in Wasser-Spuren: Festschrift für Wolfram Naumann zum 65. Geburtstag, ed. Stanca Scholz-Cionca. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1997.

- Miller, Roy Andrew, "Plus Ça Change...", The Journal of Asian Studies, August 1980.

- Miyake, Marc Hideo, Old Japanese: A Phonetic Reconstruction. New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003.

- Mori Koichi, "継体王朝と百済", in 古代の河内と百済, ed. Hirakata Rekishi Forum Jikko Iinkai. Hirakata: Daikoro Co., 2001.

- Mori Ikuo, "Korean Influence and Japanese Innovation in Tiles of the Asuka-Hakuho Period", in Transmitting the Forms of Divinity: Early Buddhist Art from Korea and Japan, eds. Washizuka Hiromitsu, et al. New York: Japan Society, 2003.

- Nakamura, Shintaro, 日本と中国の二千年. Tokyo: Toho Shuppan, 1981.

- Nakazono, Satoru, "The Role of Long-Distance Interaction in the Socio-Cultural Change in Yayoi Period, Japan ", in Coexistence and Cultural Transformation in East Asia, eds. Naoko Matsumoto, et al. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press, 2011.

- Needham, Joseph, and Tsien Tsuen-hsuin, Science and Civilisation in China: Volume Five, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- Needham, Joseph, and Wang Ling, Science and Civilisation in China: Volume Four, Physics and Physical Technology, Part Two, Mechanical Engineering. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965.

- Pai, Hyung Il, Constructing "Korean" Origins: A Critical Review of Archaeology, Historiography, and Racial Myth in Korean State-formation Theories. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2000.

- Pak, Song-nae, Science and Technology in Korean History: Excursions, Innovations, and Issues. Fremont, California: Jain, 2005.

- Portal, Jane, Korea: Art and Archaeology. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

- Pratt, Keith and Rutt, Richard, Korea: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press, 1999.

- Reischauer, Edwin O., Ennin's travels in Tʻang China. Ronald Press Company, 1955

- Rhee, Song-Nai, Aikens, C. Melvin, Choi, Sung-Rak, and Ro, Hyuk-Jin, "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan". Asian Perspectives, Fall 2007. JSTOR 42928724

- Rosner, Erhard, Medizingeschichte Japans. Leiden: BRILL, 1988.

- Sansom, George. A History of Japan Volume One. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1958.

- Sato, Seizaburo, "Response to the West: The Korean and Japanese Patterns", in Japan: A Comparative View, ed. Albert M Craig. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979.

- Seeley, Christopher, A History of Writing in Japan. New York: EJ Brill, 1991.

- Shin, Gi-Wook, Ethnic Nationalism in Korea: Genealogy, Politics, and Legacy. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006.

- Shively, Donald, "Popular Culture", in The Cambridge History of Japan Volume Four, ed. John Whitney Hall. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Tokyo National Museum, Pageant of Japanese Art: Textiles and Lacquer. Tokyo: Toto Bunka, 1952.

- Totman, Conrad, Japan: An Environmental History. London: IB Tauris, 2014.

- Tucker, Mary Evelyn, Moral and Spiritual Cultivation in Japanese Neo-Confucianism: The Life and Thought of Kaibara Ekken (1630–1714). Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989.

- von Ragué, Beatrix, A History of Japanese Lacquerwork. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1976.

- Wang Zhenping, Ambassadors from the Islands of Immortals: China-Japan Relations in the Han-Tang period. University of Hawaii Press, 2005.

- Williams, Yoko, Tsumi - Offence and Retribution in Early Japan. New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003.

- Xu, Stella, Reconstructing Ancient Korean History: The Formation of Korean-ness in the Shadow of History. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2016.

External links

- Purple Tigress. "Review: Brighter than Gold – A Japanese Ceramic Tradition Formed by Foreign Aesthetics". BC Culture. Archived from the original on January 18, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Japan, 1400–1600 A.D." Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2002. Archived from the original on March 18, 2008. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Yayoi Culture (ca. 4th century B.C.–3rd century A.D.)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

- "Yayoi Era". Mankato, MN, U.S.A.: E-museum, Minnesota State University. Archived from the original on February 26, 2011. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Japanese History: Jomon, Yayoi, Kofun: Early Japan (until 710)". japan-guide.com. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

- "Japan and Korean Influences". New York Times, The. 1901-07-07. Magazine supplement. (first paragraph only. PDF scan of full article here: )