This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Headbomb (talk | contribs) at 04:59, 10 July 2023 (1818021). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 04:59, 10 July 2023 by Headbomb (talk | contribs) (1818021)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Market dominated by a small number of sellers Not to be confused with oligarchy, although oligarchs can also be oligopolists.| This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. You can assist by editing it. (August 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Competition law |

|---|

|

| Basic concepts |

| Anti-competitive practices |

|

| Enforcement authorities and organizations |

| Quantity | one | two | few |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sellers | Monopoly | Duopoly | Oligopoly |

| Buyers | Monopsony | Duopsony | Oligopsony |

An oligopoly (from Ancient Greek Template:Wiktgrc (olígos) 'few' and Template:Wiktgrc (pōléō) 'to sell') is a market in which control over an industry lies in the hands of a few large sellers who own a dominant share of the market. Oligopolistic markets can be described as having homogenous products, few market participants and inelastic demand for the products in those industries. As a result of the significant market power firms tend to have in oligopolistic markets, these firms are exposed to the privilege of influencing prices through manipulating the supply function. In addition to that, these firms can be described as mutually interdependent. This is because any action by one firm is expected to affect other firms in the market and evoke a reaction or consequential action. To remedy that, firms in oligopolistic markets often resort to collusion as means of maximising profits.

Many industries have been cited as oligopolistic, including civil aviation, electricity providers, the telecommunications sector, rail freight markets, food processing, funeral services, sugar refining, beer making, pulp and paper making, and automobile manufacturing.

Many jurisdictions deem collusion to be illegal as it violates competition laws and is regarded as anti-competition behaviour. The EU competition law in Europe prohibits anti-competitive practices such as price-fixing and manipulating market supply and trade among competitors. In the US, the United States Department of Justice Antitrust Division and the Federal Trade Commission are tasked with stopping collusion. In Australia, The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission(ACCC) issued the Federal Competition and Consumer Act 2010, whose mandate is to preserve and promote market competition by prohibiting or regulating anti-competitive agreements and practices. Although aggressive, these laws can only apply when the firms engage in formal collusion such as cartels. This means that corporations can evade legal consequences through tacit collusion, as collusion can only be proven through actual and direct communication between companies.

It is possible for oligopolies to develop without collusion and in the presence of fierce competition among market participants. This is a situation similar to perfect competition, where oligopolists have their own market structure. In this situation, each company in the oligopoly has a large share in the industry and plays a pivotal, unique role. With post-socialist economies, oligopolies may be particularly pronounced. For example in Armenia, where business elites enjoy oligopoly, 19% of the whole economy is monopolized (BEEPS 2009 database), making it the most monopolized country in the region.

Types of oligopolies

The following characterizations of oligopolies broadly cover the many different types that have been considered in academic literature.

- Perfect and imperfect oligopolies

Perfect and imperfect oligopolies are often distinguished by the nature of the goods the firms in those markets produce or trade in.

A perfect (or sometimes called a 'pure') oligopoly is present where the commodities produced by the firms are homogenous (i.e., identical or materially the same in nature) and the elasticity of the substitution nears the infinite. Generally, where there are two homogenous products, a rational consumer's preference between the products will be indifferent (assuming the products share common prices), and similarly, sellers will be relatively indifferent between purchase commitments in relation to homogenous products. In the oligopolistic market of a primary industry, such as agriculture or mining, the commodities produced by such oligopolistic enterprises will have strong homogeneity, and as such are described as perfect oligopolies.

Imperfect (or 'differentiated') oligopolies, on the other hand, involve firms producing commodities which are heterogenous (i.e., diverse or different in content). The differentiation of goods in the manufacturing and service industries indicates that these firms are subject to an imperfect oligopoly. For example, different clothing companies may appeal to different demographics and thus need to produce a wide range of products, and different mobile phone brands have different functions and appearances, and as such offer a diverse range of products and services (the list goes on).

- Open and closed oligopolies

An open oligopoly market structure is considered to occur where the barriers to entry do not exist. Firms can freely enter the oligopolistic market. In contrast, a closed oligopoly is where there are prominent barriers to market entry in place which preclude other firms from entering the market so easily. Entry barriers include high investment requirements, strong consumer loyalty for existing brands, regulatory hurdles and economies of scale. These barriers allow existing firms in the oligopoly market to maintain a certain price on commodities and services which goes to the crux of their profit maximizing scheme.

- Collusive oligopoly

Collusion among firms in an oligopoly market structure occurs where there are express or tacit agreements (i.e., tacit collusion) between firms to follow a particular price structure in relation to particular products (if they are homogenous products) or particular transaction or product classes (if the products are heterogeneous). The colluding firms are able to profit maximize at a level above the normal market equilibrium in which other firms in the market typically maximize at. The concept of interdependence (discussed below) present in oligopolies is reduced when firms collude because there is a lessened need for firms to anticipate firms actions in relation to prices. Collusion closes the gap in the asymmetry of information typically present in a market of competing firms. One of its forms is a cartel, a monopolistic organization and relationship formed by the manufacturers who produce or sell a certain kind of goods in order to monopolize the market and obtain high profits by reaching an agreement on commodity price, output and market share allocation. However, the stability and effectiveness of a cartel are limited, and its members tend to break through the alliance to gain short-term benefits.

- Partial and full oligopoly

A firm which dominates an industry through saturation of the market (i.e., produces at a high percentage of total output) and has influence over market conditions, operates in such a way that it is able to price-make rather than price-take. This sort of firm is a price leader in oligopoly theory, and in markets where there is a price leader who dominates the other firms (the 'followers') for market control, this is described as a partial oligopoly.

Ipso facto, a full oligopoly is one in which a price leader is not present in the market, and the firms enjoy relatively similar market control.

- Tight and loose oligopoly

In a tight oligopoly, a few firms dominate the market, and there is limited competition. A loose oligopoly, on the other hand, has many firms but they are all interdependent and often collude to maximize their profits. They can be classified according to the four-firm concentration ratio, calculated by adding up the percentage market share of the top four firms in the industry. The higher the four-firm concentration ratio is, the less competitive the market is. When the four-firm concentration ration is higher than 60, the market can be classified as a tight oligopoly. A loose oligopoly occurs when the four-firm concentration is in the range of 40-60.

Characteristics of oligopolies

There are many characteristics of oligopolies. Some of these characteristics include:

- Profit maximization: an oligopoly will maximize its profits.

- Price setting: firms in an oligopoly market structure tend to be price setters rather than prices takers.

- High barriers to entry and exit: the most important barriers are government licenses, economies of scale, patents, access to expensive and complex technology, and strategic actions by incumbent firms designed to discourage or destroy nascent firms. Additional sources of barriers to entry often result from government regulation favoring existing firms making it difficult for new firms to enter the market.

- Few firms in the market (but more than one): there are so few firms that the actions of one firm can influence the actions of the other firms.

- Abnormal long run profits: Oligopolies retain abnormal long run profits. High barriers of entry prevent sideline firms from entering the market to capture excess profits. If the firms are colluding in the oligopoly, the firms can set the price at a high profit maximising level.

- Nature of the products: it can be homogeneous (for example steel) or heterogenous (for example automobiles).

- Perfect and imperfect knowledge: Assumptions about perfect knowledge vary, but the knowledge of various economic factors can be generally described as selective. Oligopolies have perfect knowledge of their own cost and demand functions, but their inter-firm information may be incomplete. If the firms in the oligopolies are colluding, information between the firms then may become perfect. Buyers, however, only have imperfect knowledge as to price, cost, and product quality

- Interdependence: the distinctive feature of an oligopoly is interdependence. Oligopolies are typically composed of a few large firms. Each firm is so large that its actions affect market conditions. Therefore, the competing firms will be aware of a firm's market actions and will respond appropriately. This means that in contemplating a market action, a firm must take into consideration the possible reactions of all competing firms and the firms' countermoves. It is very much like a game of chess, in which a player must anticipate a whole sequence of moves and countermoves in order to determine how to achieve his or her objectives; this is known as game theory. For example, an oligopoly considering a price reduction may wish to estimate the likelihood that competing firms would also lower their prices for retaliation and possibly trigger a ruinous price war. Or if the firm is considering a price increase, it may want to know whether other firms will also increase prices or hold existing prices constant. This anticipation leads to price rigidity, as firms will only be willing to adjust their prices and quantity of output in accordance with a "price leader" in the market. An example for this interdependence among oligopolists such that Texaco needs to take into consideration whether its own price cut will trigger Shell's incentive to match, and so that the benefit or privilege gained by low price would be eliminated. This high degree of interdependence and need to be aware of what other firms are doing or might do stands in contrast with the lack of interdependence in other market structures. Simply put, every oligopolistic company that appears in companies with strong commodity homogeneity is reluctant to raise or lower prices. For example, if company A increases its price but B does not, A will lose all the market in an instant; if A decreases its price, B will inevitably decrease its price, which will lead to a price war for both parties and ultimately lose both sides. Therefore, raising or lowering the price does not do itself any good, and the best strategy is to keep the price the same. The price rigidity caused by the mutual game between oligopolistic enterprises is called interdependence. In a perfectly competitive (PC) market there is zero interdependence because no firm is large enough to affect market price. All firms in a PC market are price takers, as the current market selling price can be followed predictably to maximize short-term profits. In a monopoly, there are no competitors to be concerned about. In a monopolistically-competitive market, each firm's effects on market conditions are so negligible as to be safely ignored by competitors.

- Non-price competition: Generally speaking, the oligopolistic enterprise with the largest scale and the lowest cost will become the price setter in this market, and the price set by it will maximize its own interests and ensure that other small-scale enterprises also benefit. Oligopolies tend to compete on terms other than price. Loyalty schemes, advertisement, and product differentiation are all examples of non-price competition, which is perceived less risky and brings less disastrous impacts to business. In other words, oligopolists are able to extract more rents (charge prices above normal competition level without losing large consumers) by offering differentiated products or initiating promotion efforts. However, collusion among oligopolists is harder to sustain along such non-price dimensions such as differentiation, marketing, product design. For fighting collusion and cartels in an oligopoly market, competition authorities have taken measures or practices to effectively discover, prosecute and penalize them. Leniency program and economic analysis (screening) are currently two popular mechanisms.

Sources of oligopoly power

Oligopolies derive their power and unique profit maximising abilities from various sources. Examples of sources of oligopoly power include:

- Economies of scale

Economies of scale occurs where a firm's average costs per unit of output decreases but the scale of the firm or output being produced by the firm increases. This inverse relationship between the costs and the scale of the firm leads to the firm being more productive and economically efficient. Firms in an oligopoly who benefit from economies of scale have a distinct advantage over firms who do not. Their marginal costs are lower and the firm's equilibrium at would be higher. Economies of scale is seen prevalently when two firms in oligopolistic market agree to a merger, as it not only allows the firm to diversify their market, but also allows the firm to increase in size and output production with negligible relative increases in output costs. These sorts of mergers are typically seen when companies expand into large business groups by appreciating and increasing capital to buy smaller companies in the same markets, which consequently increases the profit margins of the business. The fundamental reason oligopolies form is related to future retaliation and deviation.

- Collusion and price cutting

In a market with low entry barriers, price collusion between established sellers makes new sellers vulnerable to undercutting. Recognizing this vulnerability, the established sellers will reach a tacit understanding to raise entry barriers to prevent new companies from entering the market. Even if this requires cutting prices, all companies benefit because they reduce the risk of loss created by new competition. In other words, firms will lose less for deviation and thus have more incentive to undercut collusion prices (obtain short-term deviated profit) when more join the market. The rate at which firms interact with one another is also expected to affect the incentives for undercutting other firms as the short-term rewards for undercutting competitors will be short lived where interaction is frequent and a degree of 'punishment' can expected swiftly by other firms, but longer-lived where interaction is infrequent. Resultingly greater market transparency, in this case pertaining to the knowledge other firms have of prices and quantities of sales in rival firms, would decrease collusion. As oligopolistic companies would expect retaliation sooner where changes in their prices and quantity of sales are clear to their rivals.

- Barriers to enter the market

The barriers to enter into an oligopoly market have been discussed previously, but it is also a fundamental source of an oligopoly's power. The large capital investments required for entry, the intellectual property laws, certain network effects, absolute cost advantages, reputation, advertisement dominance, product differentiation, brand reliance, and others, all contribute to keeping existing firms in the market and precluding new firms from entering.

Modeling oligopolies

There is no single model describing the operation of an oligopolistic market. The variety and complexity of the models exist because two to 10 firms can compete on the basis of price, quantity, technological innovations, marketing, and reputation. However, there are a series of simplified models that attempt to describe market behavior by considering certain circumstances. Some of the better-known models are the dominant firm model, the Cournot–Nash model, the Bertrand model and the kinked demand model. As different industries have different characteristics, it is important to know which oligopoly model is more applicable for each industry.

Game theory models

With few sellers, each oligopolist is likely to be aware of the actions of their competition. According to game theory, the decisions of one firm influence and are influenced by the decisions of other firms. Strategic planning by oligopolists needs to take into account the likely responses of the other market participants. Oligopoly theory makes heavy use of game theory to model the behavior of oligopolies:

- Stackelberg's duopoly. In this model, the firms move sequentially to determine their quantities(see Stackelberg competition).

- Cournot's duopoly. In this model, the firms simultaneously choose quantities (see Cournot competition).

- Bertrand's oligopoly. In this model, the firms simultaneously choose prices (see Bertrand competition).

One main difference between industries is the capacity constraints. As both Cournot model and Bertrand model consist of the two-stage game, the Cournot model is more suitable for firms in industry that face capacity constraints, where firms set their quantity of production first, then set their prices. The Bertrand model is more applicable for industries with low capacity constraints, such as banking and insurance.

Game theory

The Nash Equilibrium in game theory is the strategy at which no player, by changing their strategy choice, can obtain higher utility if they deviate. In a standard game, one approach to determine the Nash Equilibrium, is to assess each outcome and payoff maximizing strategy for each player, and whether at least one player could benefit from deviating. If the players do not deviate from a specific strategy, the Nash Equilibrium is ascertained. The Nash Equilibrium assumes players are utility maximizing individuals and assumes a level of rational thinking.

A pareto efficient or optimal outcome occurs in a game where there is no alternative outcome that makes every player at least as well of and no other player that is strictly better off. In relation to the Nash Equilibrium, pareto optimal strategies can be classified as a subset of Nash Equilibrium strategies, where pareto optimal strategies deliver the maximum payoffs to all players. It is possible for there to be more than one Nash Equilibrium in a game, but this may not be considered the optimal situation.

Cournot-Nash model

Main article: Cournot competitionThe Cournot–Nash model is the simplest oligopoly model. The model assumes that there are two "equally positioned firms"; the firms compete on the basis of quantity rather than price and each firm makes an "output of decision assuming that the other firm's behavior is fixed." The market demand curve is assumed to be linear and marginal costs are constant. To find the Nash equilibrium one determines how each firm reacts to a change in the output of the other firm. The path to equilibrium is a series of actions and reactions. The pattern continues until a point is reached where neither firm desires "to change what it is doing, given how it believes the other firm will react to any change". The equilibrium is the intersection of the two firm's reaction functions. The reaction function shows how one firm reacts to the quantity choice of the other firm. The reaction function can be derived by calculating the first-order condition (FOC) of firm1's and firm2's optimal profits. To calculate the FOC is to set the first derivative of the objective function to zero. For example, assume that the firm 's demand function is where is the quantity produced by the other firm and is the amount produced by firm , and is the market. Assume that marginal cost is . Firm wants to know its maximizing quantity and price. Firm begins the process by following the profit maximization rule of equating marginal revenue to marginal costs. Firm 's total revenue function is . The marginal revenue function is .

Equation 1.1 is the reaction function for firm . Equation 1.2 is the reaction function for firm .

To determine the Nash equilibrium you can solve the equations simultaneously. The equilibrium quantities can also be determined graphically. The equilibrium solution would be at the intersection of the two reaction functions. Note that if you graph the functions the axes represent quantities. The reaction functions are not necessarily symmetric. The firms may face differing cost functions in which case the reaction functions would not be identical nor would the equilibrium quantities.

Bertrand Model

Main article: Cournot competitionThe Bertrand model is essentially the Cournot–Nash model, except the strategic variable is price rather than quantity.

Bertrand's Model can be used to explain oligopoly. Bertrand's Model thinks competition as two firms compete in the market, such as firm one and your competitors(=the rest of the market as another firm). The model assumes that firms are selling homogeneous products and therefore have the same marginal production costs, and firms will focus on competing in prices simultaneously. The idea is that after competing in prices for a while, they would eventually reach an equilibrium where the price both charge would be the same as their marginal cost of production. The mechanism behind this model is that even by undercutting just a small increment of its price, a firm would be able to capture the entire market share. The attempetion is very high and firms will have strong incentives to undercut their competitors in prices to grab the whole market profits. Even though empirical studies suggest that firms can easily make much higher profits by agreeing on charging a price that is higher than marginal costs, highly rational selfish firms would still not be able to stay at a price higher than marginal cost. It is worth noting that, Bertrand price competition is a useful abstraction of markets in many settings. Amongst many different prediction approaches, the Nash equilibrium approach has been recognised by some studies as an relatively efficient analytic tool. However, due to its lack of ability to capture human behavioural patterns, the approach has been criticised for being inaccurate in predicting prices. The model assumptions are:

- There are two firms in the market

- They produce a homogeneous product

- They produce at a constant marginal cost

- Firms choose prices and simultaneously

- Firms outputs are perfect substitutes

- Sales are split evenly if

The only Nash equilibrium is .Neither firm has any reason to change strategy. If the firm raises prices, it will lose all its customers. If the firm lowers price then it will be losing money on every unit sold.

The Bertrand equilibrium is the same as the competitive result. Each firm will produce where and there will be zero profits. A generalization of the Bertrand model is the Bertrand–Edgeworth model that allows for capacity constraints and a more general cost function.

Cournot-Bertrand model

The Cournot model and Bertrand model are the most well-known models in oligopoly theory, and have been studied and reviewed by numerous economists. The Cournot-Bertrand model is a hybrid of these two models and was first developed by Bylka and Komar in 1976. This model allows the market to be split into two groups of firms. The first groups' aim is to optimally adjust their output to maximise profits while the second groups' aim is to optimally adjust their prices. This model is not accepted by some economists who believe that firms in the same industry cannot compete with different strategic variables. However, this model has been applied and observed in both real-world examples and theoretical contexts.

In the Cournot model and Bertrand model, it is assumed that all the firms are competing with the same choice variable, either output or price. However, this does not always apply in real world contexts. If each firm is able to choose their own strategic variable, there would be a total of four modes of competition. The possibility of firms competing with different strategic variables is important to consider when assessing all potential market outcomes. Economists Kreps and Scheinkman's research demonstrates that varying economic environments are required in order for firms to compete in the same industry while using different strategic variables. An example of the Cournot-Bertrand model in real life can be seen in the market of alcoholic beverages. The production times of alcoholic beverages differ greatly creating different economic environments within the market. The fermentation of distilled spirits takes a significant amount of time; therefore, output is set by producers, leaving the market conditions to determine price. Whereas, the production of brandy requires minimal time to age, thus the price is set by the producers and the supply is determined by the quantity demanded at that price.

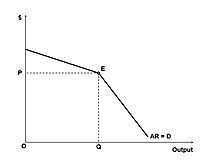

Kinked demand curve model

Main article: Kinked demandIn an oligopoly, firms operate under imperfect competition. With the fierce price competitiveness created by this sticky-upward demand curve, firms use non-price competition in order to accrue greater revenue and market share.

"Kinked" demand curves are similar to traditional demand curves, as they are downward-sloping. They are distinguished by a hypothesized convex bend

with a discontinuity at the bend–"kink". Thus, the first derivative at that point is undefined and leads to a jump discontinuity in the marginal revenue curve.

Classical economic theory assumes that a profit-maximizing producer with some market power (either due to oligopoly or monopolistic competition) will set marginal costs equal to marginal revenue. This idea can be envisioned graphically by the intersection of an upward-sloping marginal cost curve and a downward-sloping marginal revenue curve (because the more one sells, the lower the price must be, so the less a producer earns per unit). In classical theory, any change in the marginal cost structure (how much it costs to make each additional unit) or the marginal revenue structure (how much people will pay for each additional unit) will be immediately reflected in a new price and/or quantity sold of the item. This result does not occur if a "kink" exists. Because of this jump discontinuity in the marginal revenue curve, marginal cost, s could change without necessarily changing the price or quantity.

The motivation behind this kink is the idea that in an oligopolistic or monopolistic competitive market, firms will not raise their prices because even a small price increase will lose many customers. This is because competitors will generally ignore price increases, with the hope of gaining a larger market share as a result of now having comparatively lower prices (price rigidity). However, even a large price decrease will gain only a few customers because such an action will begin a price war with other firms. The curve is, therefore, more price-elastic for price increases and less so for price decreases. Theory predicts that firms will enter the industry in the long run since market price for oligopolists is more stable or 'focal' in the long run under this kinked demand curve situation.

Assumptions

According to the kinked-demand model, each firm faces a demand curve kinked at the existing price. The conjectural assumptions of the model are; if the firm raises its price above the current existing price, competitors will not follow and the acting firm will lose market share and second, if a firm lowers prices below the existing price then their competitors will follow to retain their market share and the firm's output will increase only marginally. In other words, oligopolist's pricing logic is that competitors will match and respond to any price cut - retaliating to obtain more market share, while they will stick with the current or initial price for any price rising among competitors.

If the assumptions hold, then:

- The firm's marginal revenue curve is discontinuous (or rather, not differentiable), and has a gap at the kink

- For prices above the prevailing price the curve is relatively elastic

- For prices below the point the curve is relatively inelastic

The gap in the marginal revenue curve means that marginal costs can fluctuate without changing equilibrium price and quantity, thus, prices tend to be rigid.

Other descriptions

As a quantitative description of oligopoly, the four-firm concentration ratio is often utilized and is the most preferable ratio for analyzing market concentration. This measure expresses, as a percentage, the market share of the four largest firms in any particular industry. For example, as of fourth quarter 2008, if we combine the total market share of Verizon Wireless, AT&T, Sprint, and T-Mobile, we see that these firms, together, control 97% of the U.S. cellular telephone market. These four cellular telephone firms have become the top-tier in US carriers and were protected by the US government that acted as an intervention for other firms entering the market.

Oligopolies in countries with competition laws

Oligopolies are assumed to be aware of competition laws as well as the repercussions that they could face if caught engaging in anti-competition behaviour. In lieu of being explicit, firms may be observed as engaging in coordinated interactions such as price leadership. Due to their mutually interdependent nature, firms can display parallel behaviour such as charging similar prices without it being considered as collusion.

Oligopolistic markets achieve maturity when players in the market learn that they realise more profits through joint efforts designed to maximize price control by minimizing the influence of competition. As a result of operating in countries with enforced antitrust laws, oligopolists will operate under tacit collusion, which is collusion through a mutual understanding among the competitors of a market without any direct communication or contact that by collectively raising prices, each participating competitor can achieve economic profits comparable to those achieved by a monopolist while avoiding the explicit breach of market regulations. Hence, the kinked demand curve for a joint profit-maximizing oligopoly industry can model the behaviors of oligopolists' pricing decisions other than that of the price leader (the price leader being the entity that all other entities follow in terms of pricing decisions). This is because if an entity unilaterally raises the prices of their good/service and competing entities do not follow, the entity that raised their price will lose a significant market as they face the elastic upper segment of the demand curve.

As the joint profit-maximizing efforts achieve greater economic profits for all participating entities, there is an incentive for an individual entity to "cheat" by expanding output to gain greater market share and profit. In the case of oligopolist cheating, when the incumbent entity discovers this breach in collusion, competitors in the market will retaliate by matching or dropping prices lower than the original drop. Hence, the market share originally gained by having dropped the price will be minimized or eliminated. This is why on the kinked demand curve model the lower segment of the demand curve is inelastic. As a result, in such markets price rigidity prevails.

Countries' attempt to police anticompetitive behaviour

For fighting collusion and cartels in an oligopoly market, competition authorities have taken measures or practices to effectively discover, prosecute and penalize them. Leniency program and economic analysis (screening) are currently two popular mechanisms.

Leniency program

Competition authorities prominently have roles and responsibilities on prosecuting and penalizing existing cartels and desisting new ones. Thus, authorities have created an effective tool called the leniency program, which makes antitrust firms to be more proactive participants in confessing their collusion behaviors in that they will be granted immunity from fines and still have a right to plea bargaining if not receive a full reduction. Nowadays, leniency program has been implemented by several countries like US, Japan and Canada. However, it causes negative impacts to competition authorities themselves in the wake of abusing of leniency program that there are still many cartels in society and the expected sanctions for colluded firms will experience a sharp drop. As a result, the total effect of the leniency program is ambiguous and an optimal leniency program is required.

Economic analysis (screening)

There are two screening methods that are currently available for competition authorities: structural and behavioral. In terms of structural screening, it refers to identify industry traits or characteristics, such as homogeneous goods, stable demand, less existing participants, which are prone to cartel formation. While regarding behavioral one, is mainly implemented when a cartel formation or agreement has reached and subsequently authorities start to look into firms' data and figure out whether their price variance is low or has a significant price increase or decrease.

Oligopolies in international trade

International trade has increased from $5 trillion USD in 1994 to $24 trillion USD in 2014. Following current trends, this number will only increase in the future as an increasing of firms are now competing internationally. Different from domestic oligopolies, international oligopolies have to consider importing and exporting tariffs as countries have different international policies. This is described as "strategic trade policy" and uses both the Bertrand and Cournot models as examples of interdependence.

Game theory is used when theorizing international trade theory. The added features are "That oligopolistic firms would treat markets in each country as segmented tegrated and the second, that countries had a motive to raise domestic welfare by shifting rents from foreign firms to the domestic economy in the form of higher domestic profits, increased government revenue or above-normal wages." (Head & Spencer, 2017).

Possible outcomes of oligopoly market structures

Formation of cartels

Oligopolistic competition can give rise to a wide range of outcomes. In some situations, particular companies may employ restrictive trade practices (collusion, market sharing etc.) in order to inflate prices and restrict production in much the same way that a monopoly does. Whenever there is a formal agreement for such collusion between companies that usually compete with one another, this practice is known as a cartel. A prime example of such a cartel is OPEC, where oligopolistic countries manipulate the worldwide oil supply and ultimately leaves a profound influence on the international price of oil.

There are legal restrictions on such collusion in most countries and relevant regulations or enforcements against cartels (anti-competitive behaviours) enacted since the late of 1990s. For example, EU competition law has prohibited some unreasonable anti-competitive practises such as directly or indirectly fix selling prices, manipulate market supply or control trade among competitors etc., either by means of formal contracts or oral agreements. In the US, the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department and Federal Trade Commission was created to fight collusion among cartels. However, a formal agreement is not a requirement for collusion to take place, as tacit collusion can be achieved through mutual understanding among firms. For the collusion to be prosecuted as a crime there must be actual and direct communication between companies. For example, in some industries there may be an acknowledged market leader that informally sets prices to which other producers respond, (known as price leadership). Tacit collusion is becoming a more popular topic in the development of anti-trust law in most countries.

Possibility of efficient outcomes

In other situations, competition between sellers in an oligopoly can be fierce, with relatively low prices and high production. Hypothetically, this could lead to an efficient outcome approaching perfect competition. The competition in an oligopoly can be greater when there are more competitors in an industry. Theoretically, it is harder to sustain cartels (anti-competitive behaviors) in an industry with a larger number of firms in that it will yield less collusive profit for each firm. Consequently, existing firms may have more incentive to deviate. However, this conclusion is a bit more intuitive and empirical evidence has shown this conclusion or relationship is a bit more ambiguous and mixed.

Thus the welfare analysis of oligopolies is sensitive to the parameter values used to define the market's structure. In particular, the level of dead weight loss is hard to measure. The study of product differentiation indicates that oligopolies might also create excessive levels of differentiation in order to stifle competition, as they could gain certain marker power by offering somewhat differentiated products.

Results from kinked-demand model

One possible outcome of oligopoly is the maintaining of a steady price as a result of a kinked demand curve. Firms in this situation concentrate their efforts on non-price competition. The kinked demand curve model suggests that prices would be relatively stable, and that firms will have little motivation to adjust their pricing in the near future. As a result, firms compete using strategies other than price competition. The firms participating in this market system are motivated by the desire to maximize their profits. Profit would be maximized at . Firms would earn a significant rise in market share if they reduced their prices. Although it is possible, it is doubtful that firms will accept this. As a result, other firms follow suit and reduce their prices as well. Because of this, demand will only grow by a marginal amount. As a result, demand for a price reduction is inelastic. It is likely that they will lose a significant portion of the market if they raise the price, since they would become uncompetitive when compared to other firms. As a result, demand is very elastic in response to price increases. Rather than assuming price rigidity, kinked demand strategies serve as a mechanism for enforcing compliance with a collusive price leadership strategy.

Price wars

Another possible outcome of oligopoly is the price war. However, despite suggestions that pricing wars might be unproductive for the business, Schendel and Balestra contend that at least some players in a price war can profit from their participation. Oligopolies can nevertheless have fierce pricing competition among their members, especially if they want to expand their market share. Oligopolies exist when firms compete with one another to reduce costs and gain market share. A common aspect of oligopolies is the ability to engage in price competition selectively. When it comes to bread and special offers, supermarkets often fight on price, but when it comes to product such as yogurt, they charge a premium.

Examples

Many industries have been cited as oligopolistic, including civil aviation, agricultural pesticides, electricity, and platinum group metal mining. In most countries, the telecommunications sector is characterized by an oligopolistic market structure. Rail freight markets in the European Union have an oligopolistic structure. In the United States, industries that have identified as oligopolistic include food processing, funeral services, sugar refining, beer making, pulp and paper making, and automobile manufacturing. Market power and market concentration can be estimated or quantified using several different tools and measurements, including the Lerner index, stochastic frontier analysis, and New Empirical Industrial Organization (NEIO) modeling, as well as the Herfindahl-Hirschman index.

See also

- Big business

- Conjectural variation

- Market failure

- Monopoly

- Monopsony

- Oligopolistic reaction

- Oligopsony

- Perfect competition

- Planned obsolescence

- Prisoner's dilemma

- Simulations and games in economics education

- Swing producer

- Unfair competition

Notes

- . can be restated as .

References

- "Archived copy". homework.study.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Archived copy". homework.study.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Hayden, Raymond (14 November 2022). "Oligopoly In The Beer Industry - Total Revenue". Hayden Economics. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- Falter, Ricardo (2010). The effects of oligopoly in the US Automobile sector on pricing and development.

- Opentextbc.ca. n.d. 10.2 Oligopoly. Available at: https://opentextbc.ca/principlesofeconomics/chapter/10-2-oligopoly/ .

- "Competition Counts". 11 June 2013. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- Dubey, Pradeep; Sondermann, Dieter (2009). "Perfect competition in an oligopoly (Including bilateral monopoly)". Games and Economic Behavior. 65: 124–141. doi:10.1016/j.geb.2008.10.009.

- Mikaelian, Hrant (2015). "Informal Economy of Armenia Reconsiered". Caucasus Analytical Digest (75): 2–6. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2022 – via Academia.edu.

- Dickson, Alex; Tonin, Simone (2021). "An introduction to perfect and imperfect competition via bilateral oligopoly". Journal of Economics. 133 (2): 103–128. doi:10.1007/s00712-020-00727-3. S2CID 233366478.

- Bain, Joe S. (May 1950). "Workable Competition in Oligopoly: Theoretical Considerations and Some Empirical Evidence". The American Economic Review. 40 (2): 35–47. JSTOR 1818021 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Stigler, George J. (February 1964). "A Theory of Oligopoly". Journal of Political Economy. 72 (1): 44–61. doi:10.1086/258853. JSTOR 1828791. S2CID 56253880.

- Saitone, Tina L.; Sexton, Richard J. (2010). "Product differentiation and Quality in Food Markets: Industrial Organization Implications". Annual Review of Resource Economics. 2 (1): 341–368. doi:10.1146/annurev.resource.050708.144154 – via ResearchGate.

- Sashi, C.M.; Stern, Louis W. (1995). "Product differentiation and market performance in producer goods industries". Journal of Business Research. 33 (2): 115–127. doi:10.1016/0148-2963(94)00062-J.

- Carter, Colin A; MacLaren, Donald (1997). "Price or Quantity Competition? Oligopolistic Structures in International Commodity Markets". Review of International Economics. 5 (3): 373–385. doi:10.1111/1467-9396.00063.

- ^ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Competition law & policy roundtable OECD - Oligopoly (1999) https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/1920526.pdf Archived 23 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- Osborne, Dale K. (August 1964). "The Role of Entry in Oligopoly Theory". The University of Chicago Press Journals. 72 (4): 396–402 – via JSTOR.

- Koutsoyiannis, Anna (1979). "Chapter 10 Collusive Oligopoly". Modern Microeconomics. Macmillian Education. pp. 237–254.

- Laffont, Jean-Jacques; Martimort, David (1997). "Collusion Under Asymmetric Information" (PDF). Econometrica. 65 (4): 875–911. doi:10.2307/2171943. JSTOR 2171943 – via JSTOR.

- "What Is a Cartel? Definition, Examples, and Legality". www.investopedia.com. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- Markham, Jesse W. (December 1951). "The Nature and Significance of Price Leadership". The American Economic Review. 41 (5): 891–905 – via JSTOR.

- "Concentration Ratio Definition, How to Calculate With Formula". www.investopedia.com. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- "Oligopoly". xplaind.com. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- Perloff, J. Microeconomics Theory & Applications with Calculus. page 445. Pearson 2008.

- ^ Hirschey, M. Managerial Economics. Rev. Ed, page 451. Dryden 2000.

- ^ Negbennebor, A: Microeconomics, The Freedom to Choose CAT 2001

- Negbennebor, A: Microeconomics, The Freedom to Choose page 291. CAT 2001

- Melvin & Boyes, Microeconomics 5th ed. page 267. Houghton Mifflin 2002

- ^ Colander, David C. Microeconomics 7th ed. Page 288 McGraw-Hill 2008.

- "Oligopoly - characteristics". 20 January 2020. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- Montez, Joao; Schutz, Nicolas (2021). "All-Pay Oligopolies: Price Competition with Unobservable Inventory Choices". The Review of Economic Studies. 88 (5): 2407–2438. doi:10.1093/restud/rdaa085.

- Oligopolistic Price Leadership and Mergers: The United States Beer Industry

- "Non-Price Competition in Oligopoly | Microeconomics". Micro Economics Notes. 7 March 2018. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- Kaplow, Louis; Shapiro, Carl (2007). Chapter 15 Antitrust. Handbook of Law and Economics. Vol. 2. pp. 1073–1225. doi:10.1016/S1574-0730(07)02015-4. ISBN 9780444531209.

- ^ Harrington, J. E. (2006). Behavioral screening and the detection of cartels. European Competition Law Annual, 51-68.

- Khemani, R.S and Shapiro, D.M, Glossary of Industrial Organisation Economics and Competition Law, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and development (OECD), 1990 at page 39.

- Applebaum, Elie (December 1981). "The Estimation of the Degree of Oligopoly Power". Journal of Econometrics. 19 (2–3): 287–299. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(82)90006-9. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- Khemani, R.S and Shapiro, D.M, Glossary of Industrial Organisation Economics and Competition Law, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and development (OECD), 1990 at page 37, 44, 57-58.

- Chaves, Vera Lúcia Jacob (2010). "Expansão da privatização/Mercantilização do ensino superior Brasileiro: A formação dos oligopólios". Educação & Sociedade. 31 (111): 481–500. doi:10.1590/S0101-73302010000200010.

- Explicit vs. tacit collusion—The impact of communication in oligopoly experiments

- ^ Ivaldi, M., Jullien, B., Rey, P., Seabright, P., & Tirole, J. (2003). The economics of tacit collusion.

- Cabral, Luís (May 2012). "Oligopoly Dynamics". International Journal of Industrial Organization. 30 (3): 278–282. doi:10.1016/j.ijindorg.2011.12.009 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- Bain, Joe S. (1956). "Chapter 5 Absolute cost advantages of Established Firms as Barriers to Entry". Barriers to New Competition. Harvard University Press.

- Khemani, R.S and Shapiro, D.M, Glossary of Industrial Organisation Economics and Competition Law, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and development (OECD), 1990 at page 10.

- Khemani, R.S and Shapiro, D.M, Glossary of Industrial Organisation Economics and Competition Law, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and development (OECD), 1990 at page 14.

- Motta, Massimo (2004). Competition Policy. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511804038. ISBN 9780521816632.

- Kreps, David M. (1989). Nash Equilibrium. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 167–168.

- Maskin, Eric (2011). "Commentary: Nash equilibrium and mechanism design". Games and Economic Behavior. 71: 9–11. doi:10.1016/j.geb.2008.12.008. S2CID 18860942 – via Elsevier.

- Nakamara, G.M.; Contesini, G.S.; Martinez, A.S. (2019). "Cooperation risk and Nash equilibirum: Quantitative description for realistic players". Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications. 515: 102–111. arXiv:1801.06505. Bibcode:2019PhyA..515..102N. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2018.09.194. S2CID 9376777.

- Aumann, Yonatan; Dombb, Yair (2010). "Pareto Efficiency and Approximate Pareto Efficiency in Routing and Load Balancing Games". International Symposium on Algorithmic Game Theory. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 6386: 66–77. Bibcode:2010LNCS.6386...66A. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-16170-4_7. ISBN 978-3-642-16169-8 – via SpringerLink.

- Das, Rohini; Goswami, Sayan; Konar, Amit (2019). "Relationship between Nash Equilibria and Pareto Optimal Solutions for Games of Pure Coordination". International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies.

- Maskin, Eric (2011). "Commentary: Nash equilibrium and mechanism design". Games and Economic Behaviour. 71: 9–11 – via Elsevier.

- This statement is the Cournot conjectures. Kreps, D.: A Course in Microeconomic Theory page 326. Princeton 1990.

- Kreps, D. A Course in Microeconomic Theory. page 326. Princeton 1990.

- Kreps, D. A Course in Microeconomic Theory. Princeton 1990.

- Samuelson, W & Marks, S. Managerial Economics. 4th ed. Wiley 2003

- Pindyck, R & Rubinfeld, D: Microeconomics 5th ed. Prentice-Hall 2001

- Pindyck, R & Rubinfeld, D: Microeconomics 5th ed. Prentice-Hall 2001

- ^ Samuelson, W. & Marks, S. Managerial Economics. 4th ed. page 415 Wiley 2003.

- Fatas, Enrique; Haruvy, Ernan; Morales, Antonio J. (2014). "A Psychological Reexamination of the Bertrand Paradox". Southern Economic Journal. 80 (4): 948–967. doi:10.4284/0038-4038-2012.264.

- There is nothing to guarantee an even split. Kreps, D.: A Course in Microeconomic Theory page 331. Princeton 1990.

- This assumes that there is no capacity restriction. Binger, B & Hoffman, E, 284–85. Microeconomics with Calculus, 2nd ed. Addison-Wesley, 1998.

- Pindyck, R & Rubinfeld, D: Microeconomics 5th ed.page 438 Prentice-Hall 2001.

- ^ Ma, Junhai; Wang, Hongwu (2013). "Complexity Analysis of a Cournot-Bertrand Duopoly Game Model with Limited Information". Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society. 2013: 6. doi:10.1155/2013/287371.

- ^ Horton Tremblay, Carol; Tremblay, Victor J. (2019). "Oligopoly Games and The Cournot–Bertrand Model: A Survey". Journal of Economic Surveys. 33 (5): 1555–1577. doi:10.1111/joes.12336. S2CID 202322675.

- ^ Maskin, Eric; Tirole, Jean (1988). "A Theory of Dynamic Oligopoly, II: Price Competition, Kinked Demand Curves, and Edgeworth Cycles". Econometrica. 56 (3): 571–599. doi:10.2307/1911701. JSTOR 1911701.

- ^ Pindyck, R. & Rubinfeld, D. Microeconomics 5th ed. page 446. Prentice-Hall 2001.

- Simply stated the rule is that competitors will ignore price increases and follow price decreases. Negbennebor, A: Microeconomics, The Freedom to Choose page 299. CAT 2001

- Kalai, Ehud; Satterthwaite, Mark A. (1994), Gilles, Robert P.; Ruys, Pieter H. M. (eds.), "The Kinked Demand Curve, Facilitating Practices, and Oligopolistic Coordination", Imperfections and Behavior in Economic Organizations, vol. 11, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 15–38, doi:10.1007/978-94-011-1370-0_2, ISBN 978-94-010-4599-5, retrieved 25 April 2021

- ^ Negbennebor, A. Microeconomics: The Freedom to Choose. page 299. CAT 2001

- Sys, C. (2009). Is the container liner shipping industry an oligopoly?. Transport Policy, 16(5), 259-270.

- Chitkara, Hirsh. "US Cellular and Charter are challenging the Big Four's dominance in the US wireless market". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- "The case for Huawei in America Archived 9 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine" ResearchGate. Retrieved 25 April 2021

- Green, E. J., Marshall, R. C., & Marx, L. M. (2014). Tacit collusion in oligopoly. The Oxford handbook of international antitrust economics, 2, 464-497.

- Green, E. J., Marshall, R. C., & Marx, L. M. (2014). Tacit collusion in oligopoly. The Oxford handbook of international antitrust economics, 2, 464-497.

- Harrington, J. (2006). Corporate leniency programs and the role of the antitrust authority in detecting collusion. Competition Policy Research Center Discussion Paper, CPDP-18-E.

- Marvão, C., & Spagnolo, G. (2015). Pros and Cons of Leniency, Damages and Screens. CLPD, 1, 47.

- ^ Choi, J. P., & Gerlach, H. Forthcoming. Cartels and Collusion: Economic Theory and Experimental Economics. Oxford Handbook on International Antitrust Economics (Oxford University Press, Oxford, England).

- Head, K., & Spencer, B. J. (2017, August). OLIGOPOLY IN INTERNATIONAL TRADE: RISE, FALL AND RESURGENCE. NBER. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.nber.org/papers/w23720 Archived 3 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine Nations, U. (2015, September). Evolution of the international trading system and its trends ... - UNCTAD. United Nations. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/tdb62d2_en.pdf Archived 30 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- "OPEC (cartel) - Energy Education". energyeducation.ca. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- Evenett, S. J., Levenstein, M. C., & Suslow, V. Y. (2001). International cartel enforcement: lessons from the 1990s. The World Bank.

- "Competition policy | Fact Sheets on the European Union | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- "Reading: Collusion or Competition? | Microeconomics". courses.lumenlearning.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- Harrington, J. E. (2012). A theory of tacit collusion (No. 588). Working Paper.

- Fonseca, M. A., & Normann, H. T. (2014). Endogenous cartel formation: Experimental evidence. Economics Letters, 125(2), 223-225.

- "Prerequisites of Oligopoly". www.coursesidekick.com. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- Bhaskar, V. (1988). "The kinked demand curve". International Journal of Industrial Organization. 6 (3): 373–384. doi:10.1016/S0167-7187(88)80018-3.

- Schendel D., P. Balestra. Rational Behavior and Gasoline Price Wars, Applied Economics, 1969. vol 1. – pp. 89-101

- ^ Gama, Adriana (2019). "Regulating the Polluters: Markets and Strategies for Protecting the Global Environment. Ovodenko, Alexander. 2017. New York, NY: Oxford University Press". Global Environmental Politics. 19 (3): 143–145. doi:10.1162/glep_r_00522. S2CID 211331231.

- Mousavian, Seyedamirabbas; Conejo, Antonio J.; Sioshansi, Ramteen (2020). "Equilibria in investment and spot electricity markets: A conjectural-variations approach". European Journal of Operational Research. 281: 129–140. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2019.07.054. S2CID 201247793.

- ^ Woohyung Lee, Tohru Naito & Ki-Dong Lee, Effects of Mixed Oligopoly and Emission Taxes on the Market and Environment Archived 5 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Korean Economic Review, Vol. 33, No. 2, Winter 2017, pp. 267-294: "we have witnessed mixed oligopolistic markets in a broad range of industries, such as oil, electricity, telecommunications, and power plants that emit pollutants during their respective production processes".

- ^ Ericsson, Magnus; Tegen, Andreas (2016). "Global PGM mining during 40 years—a stable corporate landscape of oligopolistic control". Mineral Economics. 29: 29–36. doi:10.1007/s13563-015-0076-x. S2CID 256205135.

- Borodin, Alex; Zholamanova, Makpal; Panaedova, Galina; Frumina, Svetlana (2020). "Efficiency of price competition in the telecommunications market". E3S Web of Conferences. 159: 03003. Bibcode:2020E3SWC.15903003B. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202015903003. S2CID 216529663.

It is considered that the telecommunications market has an oligopolistic structure in most countries.

- Jain, Anuradha; Bruckmann, Dirk (2017). "Application of the Principles of Energy Exchanges to the Rail Freight Sector". Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 2609: 28–35. doi:10.3141/2609-04. S2CID 115709002.

most of the rail freight markets still have an oligopolistic structure...

- ^ Lopez, Rigoberto A.; He, Xi; Azzam, Azzeddine (2018). "Stochastic Frontier Estimation of Market Power in the Food Industries". Journal of Agricultural Economics. 69: 3–17. doi:10.1111/1477-9552.12219.

- Lares, Jennifer DiCamillo; Lehenbauer, Kruti (21 November 2019). "Funeral Services: The Silent Oligopoly: An Exploration of the Funeral Industry in the United States". RAIS Journal for Social Sciences. 3 (2): 18–28.

- Alfred S. Eichner, The Emergence of Oligopoly: Sugar Refining as a Case Study (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019).

- Nathan H. Miller, Gloria Sheu & Matthew C. Weinberg, Oligopolistic Price Leadership and Mergers: The United States Beer Industry Archived 21 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine (14 June 2019).

- Eddie Watkins, The Dynamic Effects of Recycling on Oligopoly Competition: Evidence from the US Paper Industry Archived 5 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine (29 Oct 2018).

- GRIN - The effects of oligopoly in the US Automobile sector on pricing and development. 19 July 2011. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Bayer, R. C. (2010). Intertemporal price discrimination and competition. Journal of economic behavior & organization, 73(2), 273–293.

- Harrington, J. (2006). Corporate leniency programs and the role of the antitrust authority in detecting collusion. Competition Policy Research Center Discussion Paper, CPDP-18-E.

- Ivaldi, M., Jullien, B., Rey, P., Seabright, P., & Tirole, J. (2003). The economics of tacit collusion.

- Fonseca, Miguel A.; Normann, Hans-Theo (2012). "Explicit vs. Tacit collusion—The impact of communication in oligopoly experiments". European Economic Review. 56 (8): 1759–1772. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2012.09.002. hdl:10871/14991.

- Bhaskar, V. (1988). "The kinked demand curve". International Journal of Industrial Organization. 6 (3): 373–384. doi:10.1016/S0167-7187(88)80018-3.

- Gerlach, H. (2022). Section 2 - Basic Concepts. Lecture, Brisbane; University Queensland.

would be higher. Economies of scale is seen prevalently when two firms in oligopolistic market agree to a

would be higher. Economies of scale is seen prevalently when two firms in oligopolistic market agree to a  's demand function is

's demand function is  where

where  is the quantity produced by the other firm and

is the quantity produced by the other firm and  is the amount produced by firm

is the amount produced by firm  is the market. Assume that marginal cost is

is the market. Assume that marginal cost is  . Firm

. Firm  . The marginal revenue function is

. The marginal revenue function is  .

.

.

.

and

and  simultaneously

simultaneously

.Neither firm has any reason to change strategy. If the firm raises prices, it will lose all its customers. If the firm lowers price

.Neither firm has any reason to change strategy. If the firm raises prices, it will lose all its customers. If the firm lowers price  then it will be losing money on every unit sold.

then it will be losing money on every unit sold.

and there will be zero profits. A generalization of the Bertrand model is the

and there will be zero profits. A generalization of the Bertrand model is the  which is the equilibrium point and the kink point. This is a theoretical model proposed in 1947, which has failed to receive conclusive evidence for support.

which is the equilibrium point and the kink point. This is a theoretical model proposed in 1947, which has failed to receive conclusive evidence for support. . Firms would earn a significant rise in market share if they reduced their prices. Although it is possible, it is doubtful that firms will accept this. As a result, other firms follow suit and reduce their prices as well. Because of this, demand will only grow by a marginal amount. As a result, demand for a price reduction is inelastic. It is likely that they will lose a significant portion of the market if they raise the price, since they would become uncompetitive when compared to other firms. As a result, demand is very elastic in response to price increases. Rather than assuming price rigidity, kinked demand strategies serve as a mechanism for enforcing compliance with a collusive price leadership strategy.

. Firms would earn a significant rise in market share if they reduced their prices. Although it is possible, it is doubtful that firms will accept this. As a result, other firms follow suit and reduce their prices as well. Because of this, demand will only grow by a marginal amount. As a result, demand for a price reduction is inelastic. It is likely that they will lose a significant portion of the market if they raise the price, since they would become uncompetitive when compared to other firms. As a result, demand is very elastic in response to price increases. Rather than assuming price rigidity, kinked demand strategies serve as a mechanism for enforcing compliance with a collusive price leadership strategy.

. can be restated as

. can be restated as  .

.