This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Superior-wisconsin (talk | contribs) at 15:49, 21 June 2024. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 15:49, 21 June 2024 by Superior-wisconsin (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Outcome of September 11 attacks

| Part of the September 11 attacks | |

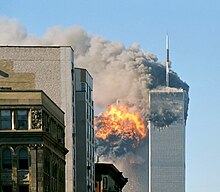

The dust cloud following the collapse of the South Tower (left), and a view of the collapse of the North Tower from the north. (right) The dust cloud following the collapse of the South Tower (left), and a view of the collapse of the North Tower from the north. (right) | |

| Date | September 11, 2001; 23 years ago (2001-09-11) |

|---|---|

| Time | 9:59 a.m. – 5:21 p.m. (EDT) |

| Location | Lower Manhattan, New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°42′42″N 74°00′45″W / 40.71167°N 74.01250°W / 40.71167; -74.01250 |

| Type | Building collapse |

| Deaths | 2,763 |

| Non-fatal injuries | c. 6,000–25,000 |

The World Trade Center in New York City collapsed on September 11, 2001, as result of the al-Qaeda attacks. Two commercial airliners hijacked by al-Qaeda terrorists were deliberately flown into the Twin Towers of the complex, resulting in a total progressive collapse that killed almost 3,000 people. It is the deadliest and costliest building collapse in history.

The North Tower (WTC 1) was the first building to be hit when American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into it at 8:46 a.m., causing it to collapse at 10:28 after burning for one hour and 42 minutes. At 9:03 a.m., the South Tower (WTC 2) was struck by United Airlines Flight 175; it collapsed at 9:59 a.m. after burning for 56 minutes.

The towers' destruction caused major devastation throughout Lower Manhattan, and more than a dozen adjacent and nearby structures were damaged or destroyed by debris from the plane impacts or the collapses. Four of the five remaining World Trade Center structures were immediately crushed or damaged beyond repair as the towers fell, while 7 World Trade Center remained standing for another six hours until fires ignited by raining debris from the North Tower brought it down at 5:21 that afternoon.

The hijackings, crashes, fires and subsequent collapses killed an initial total of 2,760 people. Toxic powder from the destroyed high-rises was dispersed throughout the city and gave rise to numerous long-term health effects that continue to plague many who were in the towers' vicinity, with at least three additional deaths reported. The 110-story towers are the tallest freestanding structures ever to be destroyed, and the death toll from the attack on the North Tower represents the deadliest terrorist act in world history.

In 2005, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) published the results of its investigation into the collapse. It found nothing substandard in the towers' design, noting that the severity of the attacks was beyond anything experienced by buildings in the past. The NIST determined the fires to be the main cause of the collapses, finding that sagging floors pulled inward on the perimeter columns, causing them to bow and then buckle. Once the upper section of the building began to move downward, a total progressive collapse was unavoidable.

The cleanup of the World Trade Center site involved round-the-clock operations and cost hundreds of millions of dollars. Some of the surrounding structures that had not been hit by the planes still sustained significant damage, requiring them to be torn down. Demolition of the surrounding damaged buildings continued even as new construction proceeded on the Twin Towers' replacement, the new One World Trade Center, which opened in 2014.

Background

When they opened in 1973, the Twin Towers were the tallest buildings in the world. At the time of the attacks only the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia and the Willis Tower (known then as the Sears Tower) in Chicago were taller. Built with a novel "framed tube" design that maximized interior space, the towers had a high strength-to-weight ratio requiring 40 percent less steel than more traditional steel framed skyscrapers. In addition, atop WTC 1 stood a 362 ft (110 m) telecommunications antenna erected in 1978, bringing that tower's total height to 1,730 ft (530 m), though as a nonstructural addition, the antenna was not officially counted.

Structural design

See also: Construction of the World Trade Center

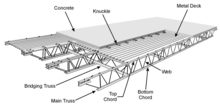

The towers were designed as framed tube structures, which provided tenants with open floor plans uninterrupted by columns or walls. The buildings were square and 207 ft (63 m) on each side but had chamfered 6 ft 11 in (2.11 m) corners, making each building's exterior roughly 210 ft (64 m) wide. One World Trade Center (WTC 1), the "North Tower", was, at 1,368 ft (417 m), six feet taller than Two World Trade Center (WTC 2), the "South Tower", which was 1,362 ft (415 m) tall. Numerous closely spaced perimeter columns provided much of the structural strength, along with gravity load shared with the steel box columns of the core. Above the tenth floor, there were 59 perimeter columns along each face of the building spaced 3 ft 4 in (1.02 m) on center. While the towers were square, the interior cores were rectangular and supported by 47 columns that ran the full height of each tower. All the elevators and stairwells were in the core, leaving a large column-free space between it and the perimeter that was bridged by prefabricated floor trusses. As the core was rectangular, this created a long and short span distance to the perimeter columns.

The floors consisted of 4 in-thick (10 cm) lightweight concrete slabs laid on a fluted steel deck. A grid of lightweight bridging trusses and main trusses supported the floors with shear connections to the concrete slab for composite action. The trusses had a span of 60 ft (18 m) in the long-span areas and 35 ft (11 m) in the short-span area. The trusses connected to the perimeter at alternate columns, and were therefore on 6.8 ft (2.1 m) centers. The top chords of the trusses were bolted to seats welded to the spandrels on the perimeter side and a channel welded to interior box columns on the core side. The floors were connected to the perimeter spandrel plates with viscoelastic dampers, which helped reduce the amount of sway felt by building occupants.

The towers also had a "hat truss" or "outrigger truss" between the 107th and 110th floors, consisting of six trusses along the long axis of core and four along the short axis. This system allowed optimized load redistribution of floor diaphragms between the perimeter and core, with improved performance between the different materials of flexible steel and rigid concrete allowing the moment frames to transfer sway into compression on the core, which also mostly supported the transmission tower. These trusses were installed in each building to support future transmission towers, but only the north tower was ultimately fitted with one.

Evaluations for aircraft impact

Though fire studies and even an analysis of the impacts of low-speed jet aircraft impacts had been undertaken before the towers' completion, the full scope of those studies no longer exists. Nevertheless, since fire had never before caused a skyscraper to collapse and aircraft impacts had been considered in their design, their destruction initially came as a surprise to some in the engineering community.

The structural engineers working on the World Trade Center considered the possibility that aircraft could crash into the building. In July 1945, a B-25 bomber that was lost in fog had crashed into the 79th floor of the Empire State Building. A year later, a C-45F Expeditor crashed into the 40 Wall Street building. Once again, fog was believed to have been the contributing factor in the collision. Leslie Robertson, one of the chief engineers working on the design of the World Trade Center, said that he considered the scenario of the impact of a Boeing 707, which might be lost in the fog and flying at relatively low speeds while seeking to land at either JFK or Newark Airports. In an interview with the BBC two months after the towers collapsed, Robertson said: "with the 707, the fuel load was not considered in the design. I don't know how it could have been considered." He also said that the main difference between the design studies and the event that caused the towers to collapse was the velocity of the impact, which greatly increased the absorbed energy, and was never considered during the construction process.

During its investigation into the collapse, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) obtained a three-page white paper that stated the buildings would survive an aircraft-impact of a Boeing 707 or DC 8 flying at 600 mph (970 km/h). In 1993, John Skilling, lead structural engineer for the WTC, said in an interview conducted after the 1993 World Trade Center bombing: "Our analysis indicated the biggest problem would be the fact that all the fuel would dump into the building. There would be a horrendous fire. A lot of people would be killed. The building structure would still be there." In its report, NIST stated that the technical ability to perform a rigorous simulation of aircraft impact and ensuing fires is a recent development, and that the technical capability for such analysis would have been quite limited in the 1960s. In its final report on the collapses, the NIST stated that it could find no documentation examining the impact of a high-speed jet or of a large-scale fire fueled by aviation fuel.

Fireproofing

Until the mid-1970s, the use of asbestos for fireproofing was widespread in the construction industry. But in April 1970, the New York City Department of Air Resources ordered contractors building the World Trade Center to stop the spraying of asbestos as an insulating material and vermiculite plaster was used instead.

After the 1993 bombing, inspections found fireproofing to be deficient. Before the collapses, the towers' owner, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, was in the process of adding fireproofing, but had completed only 18 floors in WTC 1, including all the floors affected by the aircraft impact and fires, and 13 floors in WTC 2, although none were directly affected by the aircraft impact.

NIST concluded that the aircraft impact sheared off a significant portion of the fireproofing, contributing to the buildings' collapse. In WTC 1, the impact stripped the insulation off most core columns (43 of 47) on more than one floor, as well as floor trusses over a space of 60,000 sq ft (5,600 m). In WTC 2 the impact knocked off insulation from 39 of the 47 columns on multiple floors, and also from floor trusses spanning an area of 80,000 sq ft (7,400 m).

After the collapses, Leslie E. Robertson said: "To the best of our knowledge, little was known about the effects of a fire from such an aircraft, and no designs were prepared for that circumstance. Indeed, at that time, no fireproofing systems were available to control the effects of such fires."

The two crashes

Aircraft impacts and resultant fires

During the September 11 attacks, four teams of al-Qaeda terrorists hijacked four different jetliners. Two of these jetliners, American Airlines Flight 11 and United Airlines Flight 175, both Boeing 767s, were hijacked after takeoff from Boston's Logan International Airport. In its final moments, American Airlines Flight 11 flew south over Manhattan and crashed at roughly 440 mph (710 km/h) into the northern facade of the North Tower (WTC 1) at 8:46 a.m., hitting the 93rd through 99th floors. Seventeen minutes later, United Airlines Flight 175 flew northeast, over New York Harbor, and crashed into the southern facade of the South Tower (WTC 2) at 9:03 a.m., striking between the 77th through 85th floors at 540 mph (870 km/h).

The impacts failed the exterior columns in the regions hit by the fuselage, engines, and fuel-filled wing section (34 columns in the North Tower and 26 in the South Tower). Damage also extended to the tips of the wings and tailfin. In addition, several core columns were either severed or heavily damaged, especially in the path of the fuselage.

About one third of the fuel was consumed in the initial impact and resulting fireball. Some fuel from the impact traveled down at least one elevator shaft and exploded on the 78th floor of the North Tower, as well as in the main lobby. The towers' light construction and hollowness allowed the jet fuel to penetrate far inside them, igniting many large fires simultaneously over a wide area of the impacted floors. The fuel burned for at most a few minutes, but the buildings' contents burned over the next hour or hour and a half.

As Flight 175 struck the South Tower, the shockwave shattered glass on the east face of the North Tower adjacent to the fireball, which aggravated the fires already burning in the North Tower and released plumes of smoke from the newly opened windows. It is unknown whether Flight 11's impact did the same to windows on the South Tower. In any case, the major debris from Flight 11 flew past the South Tower, while the more significant pieces of wreckage from Flight 175 similarly missed the already burning North Tower. In both instances, some of these parts landed on other nearby buildings, resulting in further destruction.

The fires in each building had different attributes, as was evident in the responses and behavior of people trapped in each. Countless windows in the North Tower were smashed by occupants seeking relief from the hellish conditions inside. While some windows were broken in the South Tower, it was relatively uncommon by comparison. Victims were only occasionally spotted inside open windows, and no crowds were present outside of the tower, as in the Impending Death photograph of the North Tower burning.

Numerous people fell or jumped to their deaths from the burning towers. Three were spotted from an east-facing window on the south side of the 79th floor, while the 100–200 people who fell or jumped from the four faces of the North Tower had no other means of escape from the insufferable heat, smoke and fire consuming its top 18 stories.

Such differences imply that conditions did not deteriorate as rapidly, or become as inhospitable, in the South Tower as in the North. The damage to the North Tower by Flight 11's centered impact severed all escape routes above the 91st floor and left the stranded workers in an insufferable inferno from which jumping was their only means of escape; Flight 175 struck the South Tower through the southeast corner of the skyscraper's southern facade and left the northwesternmost stairwell undamaged from top to bottom. The intact stairway meant people in the South Tower were not completely trapped, which may have influenced their decision to jump.

The fireballs resulting from each impact were likely very similar, but appeared vastly different in size despite the planes carrying similar amounts of combustibles. This is because a substantial portion of the jet fuel was channelled into the North Tower instead of being sprayed out into the open. Flight 11 crashed almost midway into the North Tower's central core, causing the ignited jet fuel to shoot through elevator shafts down as far as the basement and concourse levels, with a flash fire exploding from elevators in the ground floor lobby, more than 90 floors below the impact. Flight 175's impact into the South Tower's south face was offset to the east rather than being centralized like Flight 11, leaving the sides of the tower as the only real direction in which the fuel could travel, producing a visibly larger fireball on the outside.

Emergency response and evacuation

See also: Casualties of the September 11 attacks

Almost all the deaths in the Twin Towers occurred in the zones above the points of aircraft impact. As the North Tower had been struck almost directly midway into the structure, the three main stairways (A, B, and C) in the tower core were all damaged or blocked by debris preventing escape to lower floors. In the South Tower, the impact was east of center to the central section of the tower and close to the southeast corner, resulting in stairway A in the northwest portion of the central core being intact and only partially blocked, and 18 civilians managed to escape from the point of aircraft impact and the floors above that. The exact numbers of who perished and where in some cases is not precisely known; however the National Institute of Standards and Technology report indicated that a total of 1,402 civilians perished at or above the impact point in the North Tower with hundreds estimated to have been killed at the moment of impact. In the South Tower, 614 civilians perished at the impacted floors and the floors above that. Fewer than 200 of the civilian fatalities occurred in the floors below the impact points but all 147 civilian passengers and crew on the two aircraft as well as all 10 terrorists perished, along with at least 18 people on the ground and in adjacent structures.

All told, emergency personnel killed as a result of the collapse included 342 members of the New York City Fire Department (FDNY), 71 law enforcement officers including 23 members of the New York City Police Department (NYPD), 37 members of the Port Authority Police Department (PAPD), five members of the New York State Office of Tax Enforcement (OTE), three officers of the New York State Office of Court Administration (OCA), one fire marshal of the New York City Fire Department (FDNY) who had sworn law enforcement powers (and was also among the 343 FDNY members killed), one member of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and one member of the United States Secret Service (USSS). The total death toll for civilian and non-civilians is estimated to be 2,606 persons.

Collapse of the Towers

The destruction of the Twin Towers has been called "the most infamous paradigm" of progressive collapse. Each collapse began with the local failure of the vertical load-bearing components of the floors that were hit by the planes and progressed to encompass the whole of the structure. Structural components were severed, releasing gravitational energy that transferred loads downwards by way of serially propagating impact forces. Excepting the top floors of the building, which would not have released sufficient gravitational energy to bring about a total collapse, the collapses could have begun with the failure of any story.

The towers collapsed symmetrically and more or less straight down, though there was some tilting of the tops of the towers and a significant amount of fallout to the sides. As the collapse progressed, dust and debris could be seen shooting out of the windows several floors below the advancing destruction, caused by the sudden rush of air compressed under the descending upper levels.

During each collapse, large portions of the perimeter columns and the cores were left without any lateral support, causing them to fall laterally towards the outside, pushed by the increasing pile of rubble. Consequently, the walls peeled off and separated from the buildings by a large distance – about 500 ft (150 m) in some cases – hitting neighboring buildings and starting fires that would later lead to the collapse of Building 7. Some connections broke as the bolts snapped, leaving many panels randomly scattered. The first fragments of the outer walls of the collapsed North Tower struck the ground 11 seconds after the collapse started, and parts of the South Tower after 9 seconds. The lower portions of both buildings' cores (60 stories of WTC 1 and 40 stories of WTC 2) remained standing for up to 25 seconds after the start of the initial collapse before they too collapsed.

Collapse initiation

In both towers, the section of the building that had been damaged by the airplanes failed. Aside from the structural damage, the impacts had removed fireproofing from a large part of the impact zone allowing the structural steel to heat rapidly. As a result, the core columns were weakened and began to shorten due to creep. The hat truss resisted this by shifting loads to the perimeter columns. Meanwhile, web diagonals of the 60 foot trusses supporting the long-span tenant floor area began to buckle, causing the floors to sag by more than 2 feet. This pulled in the perimeter walls, which buckled. The floors above the impact zone now fell freely onto the undamaged structure below.

The North Tower lasted around 46 minutes longer than its twin, having been struck 17 minutes before the South Tower was attacked and standing another half-hour after the South Tower collapsed. This was because Flight 11 struck more or less in the center, causing more symmetrical impact damage to the North Tower's core and leaving more of its structural support intact. The fires also took more than an hour to spread to the south side of the building, where there was fireproofing damage. Traveling at 440 miles per hour, Flight 11 crashed through Floors 93 and 99, leaving only 10 floors' worth of structural weight pressing down on the damaged, burning section of the North Tower.

Flight 175's much higher impact speed inflicted structural damage even more catastrophic than Flight 11's, which was compounded by the plane slicing through the southeastern corner rather than the center, unbalancing the South Tower on one side. The uneven weight distribution was significantly aggravated by Flight 175 crashing much lower down, between Floors 77 and 85, resulting in more pressure on both the perimeter wall columns and core columns than in the North Tower and causing them to snap more quickly. The difference in the impacts was such that a senior FDNY chief reportedly expressed strong disbelief that the North Tower would collapse even after witnessing the collapse of the South Tower, because the North had not been struck at a corner.

Total progressive collapse

When the columns failed, the entire building above fell onto the first intact floor beneath impact. The vertical capacity of the connections supporting an intact floor below the level of collapse was adequate to carry the load of 11 additional floors if the load were applied gradually, but of only 6 additional floors if the load were applied suddenly— as was the case. Since the number of floors above the approximate floor of collapse initiation exceeded six in each WTC tower (12 floors in WTC 1 and 29 floors in WTC 2), the floors below the level of collapse initiation were unable to resist the suddenly applied gravitational load from the upper floors of the buildings.

From there collapse proceeded through two phases. During the crush-down phase, the upper block destroyed the structure below in a progressive series of floor failures roughly one story at a time. Each failure began with the impact of the upper block on the floor plate of the lower section, mediated by a growing layer of rubble consisting mainly of concrete from the floor slabs. The energy from each impact was "reintroduced into the structure in subsequent impact, ... concentrate in the load-bearing elements directly affected by the impact." This overloaded the floor connections of the story immediately beneath the advancing destruction, causing them to detach from the perimeter and core columns. The perimeter columns peeled away and the cores were left without lateral support.

This continued until the upper block reached the ground and the crush-up phase began. Here, it was the columns that buckled one story at a time, now starting from the bottom. As each story failed, the remaining block fell through the height of the story, onto the next one, which it also crushed, until the roof finally hit the ground. The process accelerated throughout, and by the end each story was being crushed in less than a tenth of a second.

South Tower collapse

As the fires continued to burn, occupants trapped in the upper floors of the South Tower provided information about conditions to 9-1-1 dispatchers. At 9:37 a.m., an occupant on the 105th floor of the South Tower reported that floors beneath him "in the 90-something floor" had collapsed. The New York City Police Department aviation unit also relayed information about the deteriorating condition of the buildings to police commanders. At 9:51 a.m., seven minutes before the collapse, the NYPD aviation unit reported that large pieces of debris were hanging or falling from the South Tower. The implied threat of an imminent collapse was sufficient for the NYPD to order its officers to evacuate, although none of the helicopter pilots specifically predicted that either tower would fall. During the emergency response, there was little communication between the NYPD and the FDNY, and overwhelmed 9-1-1 dispatchers did not pass along information to FDNY commanders at the scene. At 9:59 a.m., the South Tower collapsed, 56 minutes after Flight 175 crashed into it.

Before the South Tower collapsed, 18 people escaped from the impact zone and the floors above, including Stanley Praimnath, who had seen the plane coming at him. They made it out via Stairwell A, the only stairway left intact after the crash. There may have been other previously trapped occupants who were descending from the impact zone when the tower collapsed. Numerous police hotline operators who received calls from people in the South Tower were not well informed of the situation as it rapidly unfolded. Many operators told callers not to descend on their own, even though it is now believed that Stairwell A was probably passable at and above the point of impact.

North Tower collapse

The South Tower's collapse shattered windows and damaged other exterior elements along the North Tower's southern and eastern facades, although this was insufficient to cause its subsequent collapse. After the South Tower fell, NYPD helicopters relayed information about the deteriorating conditions of the North Tower, while FDNY commanders issued orders for firefighters in the North Tower to evacuate. Poor radio reception meant firefighters inside the North Tower did not hear the evacuation order from their supervisors on the scene, and most were unaware that the other tower had collapsed. An NYPD officer said at 10:06 a.m. that the North Tower was not going to last much longer and recommended that emergency vehicles be pulled away from the complex. At 10:20 a.m., the NYPD aviation unit reported that "the top of the tower might be leaning", and a minute later confirmed that the North Tower was buckling on the southwest corner and leaning to the south, prompting an officer to begin urging all NYPD personnel in the building's vicinity to retreat at least three blocks in every direction. The aviation unit declared at 10:27 "the roof is going to come down very shortly"; this proved correct less than a minute later, when the North Tower collapsed at 10:28 a.m., one hour and 42 minutes after being struck.

Because all escape routes from the impact zone, above it, and immediately below it were severed when Flight 11 crashed, no one above the 91st floor survived. The collapsing towers generated enormous clouds of dust and debris, which enveloped lower Manhattan; light dust reached as far as the Empire State Building, 2.93 mi (4.72 km) away. The debris cloud from the North Tower collapse was also larger and more widespread than that of the South Tower, because the collapse of the North also kicked up dust from the South Tower.

Building 7 collapse

Main article: 7 World Trade Center (1987–2001)

As the North Tower collapsed, heavy debris hit 7 World Trade Center, causing damage to the south face of the building and starting fires that continued to burn throughout the afternoon. Structural damage occurred to the southwest corner between Floors 7 and 17 and on the south facade between Floor 44 and the roof; other possible structural damage includes a large vertical gash near the center of the south facade between Floors 24 and 41. The building was equipped with a sprinkler system, but had many single-point vulnerabilities for failure: the sprinkler system required manual initiation of the electrical fire pumps, rather than being a fully automatic system; the floor-level controls had a single connection to the sprinkler water riser; and the sprinkler system required some power for the fire pump to deliver water. Also, water pressure was low, with little or no water to feed sprinklers.

Some firefighters entered 7 World Trade Center to search the building. They attempted to extinguish small pockets of fire, but low water pressure hindered their efforts. Fires burned into the afternoon on the 11th and 12th floors of 7 World Trade Center, the flames visible on the east side of the building. During the afternoon, fire was also seen on floors 6–10, 13–14, 19–22, and 29–30. In particular, the fires on floors 7 through 9 and 11 through 13 continued to burn out of control during the afternoon. At approximately 2:00 pm, firefighters noticed a bulge in the southwest corner of 7 World Trade Center between the 10th and 13th floors, a sign that the building was unstable and might cave to one side or "collapse". During the afternoon, firefighters also heard creaking sounds coming from the building and issued uncertain reports about damage in the basement. Around 3:30 pm FDNY Chief Daniel A. Nigro decided to halt rescue operations, surface removal, and searches along the surface of the debris near 7 World Trade Center and evacuate the area due to concerns for the safety of personnel. At 5:20:33 pm EDT on September 11, 2001, 7 World Trade Center started to collapse, with the crumble of the east mechanical penthouse, while at 5:21:10 pm EDT the entire building collapsed completely. There were no casualties associated with the collapse.

When 7 World Trade Center collapsed, debris caused substantial damage and contamination to the Borough of Manhattan Community College's Fiterman Hall building, located adjacent at 30 West Broadway, to the extent that the building was not salvageable. In August 2007, Fiterman Hall was scheduled for dismantling. A revised plan called for demolition in 2009 and completion of the new Fiterman Hall in 2012, at a cost of $325 million. The building was finally demolished in November 2009 and construction of its replacement began on December 1, 2009. The adjacent Verizon Building, an Art Deco building constructed in 1926, had extensive damage to its east facade from the collapse of 7 World Trade Center, though it was successfully restored at a cost of US$1.4 billion.

Other buildings

Many of the surrounding buildings were also either damaged or destroyed as the towers fell. 5 WTC endured a large fire and a partial collapse of its steel structure and was torn down. Other buildings destroyed include St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church, Marriott World Trade Center (Marriott Hotel 3 WTC), South Plaza (4 WTC), and U.S. Customs (6 WTC). The World Financial Center buildings, 90 West Street, and 130 Cedar Street suffered fires. The Deutsche Bank Building, the Verizon Building, and World Financial Center 3 had impact damage from the towers' collapse, as did 90 West Street. One Liberty Plaza survived structurally intact but sustained surface damage including shattered windows. 30 West Broadway was damaged by the collapse of 7 WTC. The Deutsche Bank Building, which was covered in a large black "shroud" after September 11 to cover the building's damage, was deconstructed because of water, mold, and other severe damage caused by the neighboring towers' collapse. In addition to this, many works of art were destroyed in the collapse.

Investigations

Initial opinions and analysis

In the immediate aftermath of the attacks, numerous structural engineers and experts spoke to the media, describing what they thought caused the towers to collapse. Abolhassan Astaneh-Asl, a structural engineering professor at the University of California at Berkeley, explained that the high temperatures in the fires weakened the steel beams and columns, causing them to become "soft and mushy", and eventually they were unable to support the structure above. Astaneh-Asl also suggested that the fireproofing became dislodged during the initial aircraft impacts. He also explained that, once the initial structural failure occurred, progressive collapse of the entire structure was inevitable. César Pelli, who designed the Petronas Towers in Malaysia and the World Financial Center in New York, remarked, "no building is prepared for this kind of stress."

On September 13, 2001, Zdeněk P. Bažant, professor of civil engineering and materials science at Northwestern University, circulated a draft paper with results of a simple analysis of the World Trade Center collapse. Bažant suggested that heat from the fires was a key factor, causing steel columns in both the core and the perimeter to weaken and experience deformation before losing their carrying capacity and buckling. Once more than half of the columns on a particular floor buckled, the overhead structure could no longer be supported and complete collapse of the structures occurred. Bažant later published an expanded version of this analysis. Other analyses were conducted by MIT civil engineers Oral Buyukozturk and Franz-Josef Ulm, who also described a collapse mechanism on September 21, 2001. They later contributed to an MIT collection of papers on the WTC collapses edited by Eduardo Kausel called The Towers Lost and Beyond.

Immediately following the collapses, there was some confusion about who had the authority to carry out an official investigation. While there are clear procedures for the investigation of aircraft accidents, no agency had been appointed in advance to investigate building collapses. A team was quickly assembled by the Structural Engineers Institute of the American Society of Civil Engineers, led by W. Gene Corley, Senior Vice President of CTLGroup. It also involved the American Institute of Steel Construction, the American Concrete Institute, the National Fire Protection Association, and the Society of Fire Protection Engineers. ASCE ultimately invited FEMA to join the investigation, which was completed under the auspices of the latter.

The investigation was criticized by some engineers and lawmakers in the U.S. It had little funding, no authority to demand evidence, and limited access to the WTC site. One major point of contention at the time was that the cleanup of the WTC site was resulting in the destruction of the majority of the buildings' steel components. Indeed, when NIST published its final report, it noted "the scarcity of physical evidence" that it had had at its disposal to investigate the collapses. Only a fraction of a percent of the buildings remained for analysis after the cleanup was completed: some 236 individual pieces of steel, although 95% of structural beams and plates and 50% of the reinforcement bars were recovered.

FEMA published its report in May 2002. While NIST had already announced its intention to investigate the collapses in August of the same year, by September 11, 2002 (a year after the disaster), there was growing public pressure for a more thorough investigation. Congress passed the National Construction Safety Team bill in October 2002, giving NIST the authority to conduct an investigation of the World Trade Center collapses.

FEMA building performance study

FEMA suggested that fires in conjunction with damage resulting from the aircraft impacts were the key to the collapse of the towers. Thomas Eagar, Professor of Materials Engineering and Engineering Systems at MIT, described the fires as "the most misunderstood part of the WTC collapse". This is because the fires were originally said to have "melted" the floors and columns. Jet fuel is essentially kerosene and would have served mainly to ignite very large, but not unusually hot, hydrocarbon fires. As Eagar said, "The temperature of the fire at the WTC was not unusual, and it was most definitely not capable of melting steel." This led Eagar, FEMA and others to focus on what appeared to be the weakest point of the structures, namely, the points at which the floors were attached to the building frame.

The large quantity of jet fuel carried by each aircraft ignited upon impact into each building. A significant portion of this fuel was consumed immediately in the ensuing fireballs. The remaining fuel is believed either to have flowed down through the buildings or to have burned off within a few minutes of the aircraft impact. The heat produced by this burning jet fuel does not by itself appear to have been sufficient to initiate the structural collapses. However, as the burning jet fuel spread across several floors of the buildings, it ignited much of the buildings' contents, causing simultaneous fires across several floors of both buildings. The heat output from these fires is estimated to have been comparable to the power produced by a large commercial power generating station. Over a period of many minutes, this heat induced additional stresses into the damaged structural frames while simultaneously softening and weakening these frames. This additional loading and the resulting damage were sufficient to induce the collapse of both structures.

NIST report

Main article: NIST World Trade Center Disaster Investigation

After the FEMA report had been published, and following pressure from technical experts, industry leaders and families of victims, the Commerce Department's National Institute of Standards and Technology conducted a three-year, $16 million investigation into the structural failure and progressive collapse of several WTC complex structures. The study included in-house technical expertise, along with assistance from several outside private institutions, including the Structural Engineering Institute of the American Society of Civil Engineers, Society of Fire Protection Engineers, National Fire Protection Association, American Institute of Steel Construction, Simpson Gumpertz & Heger Inc., Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, and the Structural Engineers Association of New York.

The scope of the NIST investigation was focused on identifying "the sequence of events" that triggered the collapse, and did not include detailed analysis of the collapse mechanism itself (after the point at which events made the collapse inevitable). In line with the concerns of most engineers, NIST focused on the airplane impacts and the spread and effects of the fires, modeling these using Fire Dynamics Simulator software. NIST developed several highly detailed structural models for specific sub-systems such as the floor trusses as well as a global model of the towers as a whole which is less detailed. These models were static or quasi-static, including deformation but not the motion of structural elements after rupture.

James Quintiere, professor of fire protection engineering at the University of Maryland, called the fact that only a small portion of the building's steel was preserved for study "a gross error" that NIST should have openly criticized. He also noted that the report lacked a timeline and physical evidence to support its conclusions. Some engineers have suggested that understanding of the collapse mechanism could be improved by developing an animated sequence of the collapses based on a global dynamic model, and comparing it with the video evidence of the actual collapses. The NIST report for WTC 7 concluded that no blast sounds were heard on audio and video footage, or were reported by witnesses.

7 World Trade Center

In May 2002, FEMA issued a report on the collapse based on a preliminary investigation conducted jointly with the Structural Engineering Institute of the American Society of Civil Engineers under leadership of Dr. W. Gene Corley, P.E. FEMA made preliminary findings that the collapse was not primarily caused by actual impact damage from the collapse of 1 WTC and 2 WTC but by fires on multiple stories ignited by debris from the other two towers that continued unabated due to lack of water for sprinklers or manual firefighting. The report did not reach conclusions about the cause of the collapse and called for further investigation.

In response to FEMA's concerns, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) was authorized to lead an investigation into the structural failure and collapse of the World Trade Center twin towers and 7 World Trade Center. The investigation, led by Dr S. Shyam Sunder, drew not only upon in-house technical expertise, but also upon the knowledge of several outside private institutions, including the Structural Engineering Institute of the American Society of Civil Engineers (SEI/ASCE), the Society of Fire Protection Engineers (SFPE), the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), the American Institute of Steel Construction (AISC), the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH), and the Structural Engineers Association of New York (SEAoNY).

The bulk of the investigation of 7 World Trade Center was delayed until after reports were completed on the collapse of the World Trade Center twin towers. In the meantime, NIST provided a preliminary report about 7 World Trade Center in June 2004, and thereafter released occasional updates on the investigation. According to NIST, the investigation of 7 World Trade Center was delayed for a number of reasons, including that NIST staff who had been working on 7 World Trade Center were assigned full-time from June 2004 to September 2005 to work on the investigation of the collapse of the twin towers. In June 2007, Shyam Sunder explained, "We are proceeding as quickly as possible while rigorously testing and evaluating a wide range of scenarios to reach the most definitive conclusion possible. The 7 WTC investigation is in some respects just as challenging, if not more so, than the study of the towers. However, the current study does benefit greatly from the significant technological advances achieved and lessons learned from our work on the towers."

In November 2008, NIST released its final report on the causes of the collapse of 7 World Trade Center. This followed their August 21, 2008 draft report which included a period for public comments. In its investigation, NIST utilized ANSYS to model events leading up to collapse initiation and LS-DYNA models to simulate the global response to the initiating events. NIST determined that diesel fuel did not play an important role, nor did the structural damage from the collapse of the twin towers, nor did the transfer elements (trusses, girders, and cantilever overhangs), but the lack of water to fight the fire was an important factor. The fires burned out of control during the afternoon, causing floor beams near Column 79 to expand and push a key girder off its seat, triggering the floors to fail around column 79 on Floors 8 to 14. With a loss of lateral support across nine floors, Column 79 soon buckled – pulling the East penthouse and nearby columns down with it. With the buckling of these critical columns, the collapse then progressed east-to-west across the core, ultimately overloading the perimeter support, which buckled between Floors 7 and 17, causing the entire building above to fall downward as a single unit. From collapse timing measurements taken from a video of the north face of the building, NIST observed that the building's exterior facade fell at free fall acceleration through a distance of approximately 8 stories (32 meters, or 105 feet), noting "the collapse time was approximately 40 percent longer than that of free fall for the first 18 stories of descent." The fires, fueled by office contents, along with the lack of water, were the key reasons for the collapse.

The collapse of the old 7 World Trade Center is remarkable because it was the first known instance of a tall building collapsing primarily as a result of uncontrolled fires. Based on its investigation, NIST reiterated several recommendations it had made in its earlier report on the collapse of the twin towers, and urged immediate action on a further recommendation: that fire resistance should be evaluated under the assumption that sprinklers are unavailable; and that the effects of thermal expansion on floor support systems be considered. Recognizing that current building codes are drawn to prevent loss of life rather than building collapse, the main point of NIST's recommendations is that buildings should not collapse from fire even if sprinklers are unavailable.

Other investigations

In 2003, Asif Usmani, Professor of Structural Engineering at University of Edinburgh, published a paper with two colleagues. They provisionally concluded the fires alone, without any damage from the airplanes, could have been enough to bring down the buildings. In their view, the towers were uniquely vulnerable to the effects of large fires on several floors at the same time. When the NIST report was published, Barbara Lane, with the UK engineering firm Arup, criticized its conclusion that the loss of fire proofing was a necessary factor in causing the collapses; "We have carried out computer simulations which show that the towers would have collapsed after a major fire on three floors at once, even with fireproofing in place and without any damage from plane impact." Jose L. Torero, formerly of the BRE Centre for Fire Safety Engineering at the University of Edinburgh, pursued further research into the potentially catastrophic effects of fire on real-scale buildings.

Aftermath

Main article: Aftermath of the September 11 attacksCleanup

The cleanup was a massive operation coordinated by the City of New York Department of Design and Construction. On September 22, a preliminary cleanup plan was delivered by Controlled Demolition, Inc. (CDI) of Phoenix, Maryland. Costing hundreds of millions of dollars, it involved round-the-clock operations with many contractors and subcontractors. By early November, with a third of the debris removed, officials began to reduce the number of firefighters and police officers assigned to recovering the remains of victims, in order to prioritize the removal of debris. This caused confrontations with firefighters. Despite efforts to extinguish the blaze, the large pile of debris burned for three months, until the majority of the rubble was finally removed from the site. In 2007, the demolition of the surrounding damaged buildings was still ongoing as new construction proceeded on the World Trade Center's replacement, One World Trade Center.

Health effects

Main articles: Health effects arising from the September 11 attacks and United States Environmental Protection Agency September 11 attacks pollution controversyThe collapse of the World Trade Center produced enormous clouds of dust that covered Manhattan for days. On September 18, 2001, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) assured the public that the air in Manhattan was "safe to breathe". In 2003 the EPA's inspector general found that the agency did not at that time have sufficient data to make such a statement. Dust from the collapse seriously reduced air quality and is likely the cause of many respiratory illnesses in lower Manhattan. Asbestosis is such an illness, and asbestos would have been present in the dust. Significant long term medical and psychological effects have been found among first responders including elevated levels of asthma, sinusitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Health effects also extended to residents, students, and office workers of Lower Manhattan and nearby Chinatown. Several deaths have been linked to the toxic dust, and the victims' names will be included in the World Trade Center memorial. More than 18,000 people have suffered from illnesses from the dust.

References

Explanatory notes

- ^ The exact time is disputed. The 9/11 Commission Report states that Flight 11 struck the North Tower at 8:46:40 a.m., while NIST reports 8:46:30 a.m.

- The first plane crash at 8:46:40 a.m. in the North Tower, marked the beginnings of the process leading to the collapse, but the first actual collapse initiated at 9:58:59 a.m. in the South Tower, which is rounded to 9:59 a.m.

- This total includes those killed in the hijackings, crashes, fires, collapses and subsequent health effects.

- Sources vary regarding the number of injuries suffered in the September 11 attacks―some say 6,000 while others go as high as 25,000, but it is a given that almost all of the injuries on 9/11 would have come from the crashes, fires and subsequent collapses at the World Trade Center site.

- ^ The exact time of the North Tower's collapse initiation is disputed, with NIST dubbing the moment it began to collapse as being 10:28:22 a.m. and the 9/11 Commission recording the time as 10:28:25.

- ^ While NIST and the 9/11 Commission give differing estimates on the exact second of collapse initiation, with NIST placing it at 10:28:22 a.m. and the commission at 10:28:25 a.m., it is generally accepted that Flight 11 struck the tower no sooner than 8:46:30 a.m., so the time it took for the North Tower to collapse was just shy of 102 minutes either way.

- ^ The exact time is disputed. The 9/11 Commission report states that Flight 175 struck the South Tower at 9:03:11 a.m., NIST reports 9:02:59 a.m., and some other sources suggest 9:03:02.

- ^ NIST and the 9/11 Commission both state that the collapse initiated at 9:58:59 a.m., which is rounded to 9:59 a.m. for simplicity. If the commission's claim that the South Tower was struck at 9:03:11 is to be believed, then it collapsed after 55 minutes and 48 seconds, not 56 minutes.

- The massacre at Camp Speicher―often described as the second deadliest act of terrorism after 9/11―is said to have killed between 1,095 and 1,700 people. The upper estimate would tie it with the attack on the World Trade Center's North Tower, but until the true death toll of the massacre becomes known, then the hijacking and crash of Flight 11 was the deadliest terrorist attack on record.

- The three-page white paper titled Salient points with regard to the structural design of The World Trade Center towers described an analysis of a Boeing 707 weighing 336,000 lb (152 t) and carrying 23,000 US gal (87 m) of fuel striking the 80th floor of the buildings at 600 mph (970 km/h). It is unclear whether the effect of jet fuel and aircraft contents was a consideration in the original building design, but this study is in line with remarks Archived April 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine made by John Skilling following the 1993 WTC bombing. Without original documentation for either study, NIST said any further comments would amount to speculation. NIST 2005. pp. 305–307.

- According to National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) estimates, Flight 11 was carrying 10,000 US gal (38,000 L) of jet fuel when it hit the North Tower. 1,500 US gal (5,700 L) were consumed in the initial impact when the aircraft hit and a similar amount was consumed in the fireball outside the building. Approximately 7,000 US gal (26,000 L) burnt inside the office spaces igniting combustibles. Similarly, Flight 175 was carrying around 9,100 US gal (34,000 L) of jet fuel when it hit the South Tower. Up to 1,500 US gal (5,700 L) was instantly consumed in the initial fireball and up to 2,275 US gal (8,610 L) was consumed in the fireball outside the building. More than 5,325 US gal (20,160 L) was burnt in the office spaces. NIST estimated that each floor of both buildings contained around four pounds per square foot (60 tons per floor) of combustibles.

- In total, 343 firefighters were killed at the World Trade Center, but one of them was not killed in the collapse but had been struck by a civilian falling from the South Tower.

Citations

- ^ National Institute of Standards and Technology (2005). Final Reports from the NIST World Trade Center Disaster Investigation (PDF). p. 84.

- ^ The 9/11 Commission Report (PDF). 2004. p. 305.

- "A Day of Remembrance". U.S. Embassy in Georgia. September 11, 2022. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- Stempel, Jonathan (July 29, 2019). "Accused 9/11 mastermind open to role in victims' lawsuit if not executed". Reuters. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- The 9/11 Commission Report (PDF). 2004. p. 24.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (2005). "Final report on the collapse of the World Trade Center" (PDF). NIST: 69.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (2005). Final report on the collapse of the World Trade Center (PDF).

- The 9/11 Commission Report (PDF). 2004.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (2005). "Final report on the collapse of the World Trade Center" (PDF). NIST: 69.

- ^ 9/11 Commission 2004a, pp. 7–8.

- Staff Report of the 9/11 Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States (PDF) (Report). National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. September 2005 . p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- Building and Fire Research Laboratory (September 2005). Visual Evidence, Damage Estimates, and Timeline Analysis (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology (Report). United States Department of Commerce. p. 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 11, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- "Timeline for United Airlines Flight 175". NPR. June 17, 2004. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (2005). Final Reports from the NIST World Trade Center Disaster Investigation (PDF). p. 80.

- The 9/11 Commission Report (PDF). 2004. p. 305.

- Staff Report of the 9/11 Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States (PDF) (Report). National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. September 2005 . p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- Evans, Heidi (September 8, 2013). "1,140 WTC 9/11 responders have cancer – and doctors say that number will grow". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- "1095 soldiers still missing since the Speicher massacre by ISIS". CNN Arabic (in Arabic). 18 September 2014. Archived from the original on September 20, 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- "One World Trade Center officially opens in New York City, on the site of the Twin Towers". History.com. A&E Television Networks. July 24, 2019. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- Swanson, Ana (March 11, 2015). "Charted: The tallest buildings in the world for any year in history". Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- American Iron and Steel Institute (1964). "The World Trade Center – New York City". Contemporary Steel Design. 1 (4). American Iron and Steel Institute.

- ^ McAllister, Therese; Sadak, Fahim; Gross, John; Averill, Jason; Gann, Richard (June 2008). Overview of the Structural Design of World Trade Center 1, 2, and 7 Buildings. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ Lew, H.S.; Bukowski, Richard; Carino, Nicholas (September 2005). Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster (pdf). National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on May 24, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ Bažant, Zdeněk P.; Verdure, Mathieu (March 2007). "Mechanics of Progressive Collapse: Learning from World Trade Center and Building Demolitions" (PDF). Journal of Engineering Mechanics. 133 (3): 308–319. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.121.4166. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9399(2007)133:3(308). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 2, 2008. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "Plane Crashes into Empire State Building". A&E Television Networks, LLC. Archived from the original on January 5, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Long, Adam (May 21, 1946). "Pilot Lost in Fog". The New York Times. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ Robertson, Leslie (March 1, 2002). "Reflections on the World Trade Center". National Academy of Engineering. 32 (1). Archived from the original on July 2, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "The Man who built the Twin Towers". British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Sadek, Fahim (September 1, 2005). "Baseline Structural Performance and Aircraft Impact Damage Analysis of the World Trade Center Towers. Appendices A-E. Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Nalder, Eric (February 27, 1993). "Twin Towers Engineered to Withstand Jet Collision". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on April 14, 2008. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ "Answers to Frequently Asked Questions". NIST. National Institute of Standards and Technology. August 2006. Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ^ Shyam-Sunder, Sivaraj; others (December 5, 2005). "Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster: Final Report of the National Construction Safety Team on the Collapses of the World Trade Center Towers (NIST NCSTAR 1)". NIST. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on May 8, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- "City Bars Builder's Use Of Asbestos at 7th Ave. Site". The New York Times. April 28, 1970. p. 83. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 19, 2019. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- "NIST NCSTAR 1: Final Report on the Collapse of the World Trade Center Towers" (PDF). 2009-11-08 . Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2009. Retrieved 2022-09-06.

- Morse, Roger (October 1, 2002). "Fireproofing at the WTC Towers". Fire Engineering. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- Gross, John; McAllister, Therese. "Structural Fire Response and Probable Collapse Sequence of the World Trade Center Towers (NIST NCSTAR 1-6)". National Institute of Standards and Technology. p. lxxi. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- National Transportation Safety Board, Office of Research and Engineering, https://www.ntsb.gov/about/Documents/Flight_Path_Study_AA11.pdf Archived November 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Access Date, July 31, 2021

- September 11 Attack Timeline, 9/11 Memorial and Museum, https://timeline.911memorial.org/#Timeline/2 Archived February 27, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Access Date, July 31, 2021

- National Transportation Safety Board, Office of Research and Engineering, https://www.ntsb.gov/about/Documents/Flight_Path_Study_UA175.pdf Archived June 29, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Access Date, July 31, 2021

- Sadek, Fahim (2005-12-01). "Baseline Structural Performance and Aircraft Impact Damage Analysis of the World Trade Center Towers. Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster (NIST NCSTAR 1-2)". NIST: 302–304.

- McAllister, T.; Barnett, J.; Gross, J.; Hamburger, R.; Magnusson, J. (2002), "Chapter 1 - Introduction" (PDF), in McAllister, T. (ed.), World Trade Center Building Performance Study: Data Collection, Preliminary Observations, and Recommendations, ASCE/FEMA, archived (PDF) from the original on July 28, 2014, retrieved June 17, 2013

- Ronald Hamburger; William Baker; Jonathan Barnett; Christopher Marrion; James Milke; Harold "Bud" Nelson. "2". World Trade Center Building Performance Study - Chapter 2: WTC 1 and WTC 2 (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2021.

- NCSTAR 1-5A, p 80

- Field, Andy (2004). "A Look Inside a Radical New Theory of the WTC Collapse". Fire/Rescue News. Archived from the original on June 19, 2006. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- "Initial Model for Fires in the World Trade Center Towers" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. p. 17. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ National Institute of Standards and Technology (2005). Final Reports from the NIST World Trade Center Disaster Investigation (PDF).

- "Recovery — Aircraft - Exhibitions". New York State Museum. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- ^ Federal Emergency Management Agency (2002). WTC1 and WTC2 (PDF).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (2005). Final Reports from the NIST World Trade Center Disaster Investigation (PDF). p. 86.

- Cauchon, Dennis and Martha Moore (September 2, 2002). "Desperation forced a horrific decision". USAToday. Archived from the original on September 1, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- 9/11 Commission 2004a, p. 293.

- ^ "2 Planes Hit Twin Towers at Exactly the Worst Spot". September 12, 2001. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (2005). Final report on the collapse of the World Trade Center towers (PDF). p. 73.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (2005). Final report on the collapse of the World Trade Center towers (PDF). p. 74.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (2005). Final report on the collapse of the World Trade Center towers (PDF). p. 75.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (2005). Final report on the collapse of the World Trade Center towers (PDF). p. 88.

- "Accused 9/11 plotter Khalid Sheikh Mohammed faces New York trial". Cabne News Network. November 13, 2009. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- Starossek, Uwe (2009). Progressive Collapse of Structures. Thomas Telford Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7277-3610-9.

- ^ Starossek, Uwe (2009). Progressive Collapse of Structures. Thomas Telford Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7277-3610-9.

- Starossek, Uwe (2009). Progressive Collapse of Structures. Thomas Telford Publishing. pp. 101–2. ISBN 978-0-7277-3610-9.

- Hamburger, Ronald; et al. "World Trade Center Building Performance Study" (PDF). Federal Emergency Management Agency. pp. 2–27 & 2–35. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 27, 2008. Retrieved July 27, 2006.

- ^ Lalkovski, Nikolay; Starossek, Uwe (2022). "The Total Collapse of the Twin Towers: What It Would Have Taken to Prevent It Once Collapse Was Initiated". Journal of Structural Engineering. 148 (2). doi:10.1061/(ASCE)ST.1943-541X.0003244. hdl:11420/11260.

- Gross, John L.; McAllister, Therese P. (2005-12-01). "Structural Fire Response and Probable Collapse Sequence of the World Trade Center Towers. Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster (NIST NCSTAR 1-6)". NIST: 335–336.

- Gross, John L.; McAllister, Therese P. (2005-12-01). "Structural Fire Response and Probable Collapse Sequence of the World Trade Center Towers. Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster (NIST NCSTAR 1-6)". NIST: 237, 254, 338.

- "A NATION CHALLENGED: THE TRADE CENTER CRASHES; First Tower to Fall Was Hit At Higher Speed, Study Finds". The New York Times. February 23, 2002. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- 9/11 Commission 2004a, p. 327.

- kristy.thompson@nist.gov (2011-09-14). "FAQs - NIST WTC Towers Investigation". NIST. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- Bažant, Z. K. P.; Le, J. L.; Greening, F. R.; Benson, D. B. (2008). "What Did and Did Not Cause Collapse of World Trade Center Twin Towers in New York?" (PDF). Journal of Engineering Mechanics. 134 (10): 892. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9399(2008)134:10(892). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ Lawson, J. Randall; Vettori, Robert L. (September 2005). "NIST NCSTAR 1–8 – The Emergency Response Operations" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. p. 37. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- "McKinsey Report – Increasing FDNY's Preparedness". August 19, 2002. Archived from the original on June 8, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ^ The 9/11 Commission Report (PDF). 2004. p. 305.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (2005). Final Reports from the NIST World Trade Center Disaster (PDF).

- 9/11 Commission 2004a, p. 314.

- National Commission on Terrorist Attacks (July 22, 2004). The 9/11 Commission Report (first ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 294. ISBN 978-0-393-32671-0. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- Dwyer, Jim; Flynn, Kevin; Fessenden, Ford (July 7, 2002). "9/11 Exposed Deadly Flaws in Rescue Plan". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ Lawson, J. Randall; Vettori, Robert L. (September 2005). "NIST NCSTAR 1–8 – The Emergency Response Operations" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. p. 91. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- "Final Report on the Collapse of World Trade Center Building 7" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- Stairwell sign from the World Trade Center Archived June 30, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, 2002

- ^ "Interim Report on WTC 7" (PDF). Appendix L. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2007. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ^ NIST NCSTAR1-A: Final Report on the Collapse of World Trade Center Building 7 (PDF). NIST. November 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- Grosshandler, William. "Active Fire Protection Systems Issues" (PDF). NIST. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2007. Retrieved September 11, 2007.

- Evans, David D. (September 2005). "Active Fire Protection Systems" (PDF). NIST. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- "Oral Histories From Sept. 11 – Interview with Captain Anthony Varriale" (PDF). The New York Times. December 12, 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2007. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- Spak, Steve (September 11, 2001). WTC 9-11-01 Day of Disaster (Video). New York City: Spak, Steve. Archived from the original on October 6, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- Scheuerman, Arthur (December 8, 2006). "The Collapse of Building 7" (PDF). NIST. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 29, 2009. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ "Questions and Answers about the NIST WTC 7 Investigation". NIST. May 24, 2010. Archived from the original on August 27, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- "WTC: This Is Their Story, Interview with Chief Peter Hayden". Firehouse.com. September 9, 2002. Archived from the original on January 9, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- "WTC: This Is Their Story, Interview with Captain Chris Boyle". Firehouse.com. August 2002. Archived from the original on January 9, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- "Oral Histories From Sept. 11 – Interview with Chief Daniel Nigro". The New York Times. October 24, 2001. Archived from the original on March 4, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- Gilsanz, Ramon; DePaola, Edward M.; Marrion, Christopher; Nelson, Harold "Bud" (May 2002). "WTC7 (Chapter 5)" (PDF). World Trade Center Building Performance Study. FEMA. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 5, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- CBS News (September 11, 2001). CBS Sept. 11, 2001 4:51 pm – 5:33 pm (September 11, 2001) (Television). WUSA, CBS 9, Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved March 16, 2016. – View footage Archived February 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine of the collapse captured by CBS

- "Fiterman Hall — Project Updates". Lower Manhattan Construction Command Center/LMDC. Archived from the original on September 12, 2007. Retrieved August 23, 2007.

- Fiterman is Funded Archived December 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine BMCC News, November 17, 2008

- Agovino T Ground Zero building to be razed Archived October 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Crain's New York Business November 13, 2008

- "Lower Manhattan: Fiterman Hall". LowerManhattan.info. Lower Manhattan Construction Command Center. Archived from the original on September 12, 2007. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- "Verizon Building Restoration". New York Construction (McGraw Hill). Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- "Rescuing the Buildings Beyond Ground Zero". The New York Times. February 12, 2002. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- Collins, Glenn (March 5, 2004). "9/11's Miracle Survivor Sheds Bandages; A 1907 Landmark Will Be Restored for Residential Use". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 15, 2009. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- Varchaver, Nicholas (March 20, 2008). "The tombstone at Ground Zero". CNN. Archived from the original on May 3, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- "130 Liberty Street: Project Updates". Lower Manhattan Construction Command Center. March 25, 2011. Archived from the original on March 28, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- Perlman, David (September 12, 2001). "Jets hit towers in most vulnerable spots". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- Gugliotta, Guy (September 12, 2001). "'Magnitude Beyond Anything We'd Seen Before'; Towers Built to Last But Unprepared For Such an Attack". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- Bažant, Zdeněk P.; Yong Zhou (January 2002). "Why Did the World Trade Center Collapse?—Simple Analysis" (PDF). Journal of Engineering Mechanics. 128 (1): 2–6. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9399(2002)128:1(2). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2019. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- Buyukozturk, Oral (2001). "How safe are our skyscrapers?: The World Trade Center collapse". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on September 7, 2005. Retrieved June 26, 2006.

- Kausel, Eduardo (2002). "The Towers Lost and Beyond". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on December 6, 2006. Retrieved June 26, 2006.

- Snell, Jack. "The Proposed National Construction Safety Team Act." NIST Building and Fire Research Laboratory. 2002. NIST.gov Archived November 7, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Experts Debate Future of the Skyscraper in Wake of Disaster". Engineering News-Record. September 24, 2001.

- Glanz, James; Lipton, Eric (December 25, 2001). "Experts Urging Broader Inquiry In Towers' Fall". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 19, 2020. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- Sylvie Boulanger and Sylvain Boulanger "Steel and sustainability 2: Recovery strategies" Canadian Institute of Construction. March 17, 2004. CISC-ICCA.ca Archived September 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Dwyer, Jim (September 11, 2002). "Investigating 9/11: An Unimaginable Calamity, Still Largely Unexamined". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- "NIST's Responsibilities Under the National Construction Safety Team Act". Archived from the original on April 19, 2010. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- Eagar & Musso 2001, p. 8: "The fire is the most misunderstood part of the WTC collapse. Even today, the media report (and many scientists believe) that the steel melted."

- Eagar & Musso 2001, p. 10: "The maximum flame temperature increase for burning hydrocarbons (jet fuel) in air is, thus, about 1,000 °C—hardly sufficient to melt steel at 1,500 °C."

- Eagar & Musso 2001, p. 9: "The temperature of the fire at the WTC was not unusual, and it was most definitely not capable of melting steel."

- Eagar & Musso 2001, p. 11: "It survived the loss of several exterior columns due to aircraft impact, but the ensuing fire led to other steel failures. Many structural engineers believe that the weak points—the limiting factors on design allowables—were the angle clips that held the floor joists between the columns on the perimeter wall and the core structure."

- FEMA(403) Executive Summary, p. 2.

- Newman, Michael E. (2002). "Commerce's NIST Details Federal Investigation of World Trade Center Collapse". National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- "Reports of the Federal Building and Fire Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster". NIST. March 23, 2011. Archived from the original on May 29, 2009. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- Bazant (2007), p. 2

- NIST final report (2005). NCSTAR 1, p. xxxvii.

- Committee on Science (October 26, 2005). "The investigation of the World Trade Center collapse: findings, recommendations, and next steps". commdocs.house.gov. p. 259. Archived from the original on September 23, 2007. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- Quintiere, James (December 2004). "2004 Report to Congress of the National Construction Safety Team Advisory Committee" (PDF). NIST. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- Parker, Dave (October 6, 2005). "WTC investigators resist call for collapse visualisation". New Civil Engineer. England & Wales: EMAP Publishing.

- "Questions and Answers about the NIST WTC 7 Investigation". NIST. 2012. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- "NIST's World Trade Center Investigation". NIST. May 27, 2010. Archived from the original on July 27, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- "Final Report on the Collapse of the World Trade Center Towers" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). September 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Newman, Michael (June 29, 2007). "NIST Status Update on World Trade Center 7 Investigation" (Press release). National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on August 29, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- McAllister, Therese (December 12, 2006). "WTC 7 Technical Approach and Status Summary" (PDF). NIST. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 5, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- "NIST NCSTAR 1A: Final Report on the Collapse of World Trade Center Building 7" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. November 2008. pp. 44–46. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- Usmani, A.S.; Y. C. Chung; J. L. Torero (2003). "How did the WTC towers collapse: a new theory" (PDF). Fire Safety Journal. 38 (6): 501–533. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.490.2176. doi:10.1016/S0379-7112(03)00069-9. hdl:1842/1216. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2007.

- "Row erupts over why twin towers collapsed". New Civil Engineer. 2005. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- BRE Centre for Fire Safety Engineering, University of Edinburgh (2006). "Dalmarnock Full-Scale Experiments 25 & 26 July 2006". BRE Centre for Fire Safety Engineering, University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- Christian, Nicholas (2006). "Glasgow tower block to shed light on 9/11 fire". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- "Skyscraper Fire Fighters". BBC Horizon. 2007. Archived from the original on April 5, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- Post, Nadine M. and Debra K. Rubin. "Debris Mountain Starts to Shrink." Engineering News Record, 10/1/01. Construction.com Archived February 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Kugler, Sara (October 23, 2006). "Officials Wanted More Searching at WTC". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- Rubin, Debra K.; Janice L. Tuchman (November 8, 2001). "WTC Cleanup Agency Begins Ramping Up Operations". Engineering News Record. McGraw-Hill. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- "WTC Fire Extinguished". People's Daily Online. December 20, 2001. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- "CBS News – WTC Fires All But Defeated – December 19, 2001 23:22:25". CBS News. December 19, 2001. Archived from the original on April 3, 2002. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- "EPA Response to September 11". Archived from the original on March 6, 2008. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency Office of Inspector General. "EPA's Response to the World Trade Center Collapse." Report No. 2003-P-00012. August 21, 2003. EPA.gov Archived September 15, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- "First Long-term Study of WTC Workers Shows Widespread Health Problems 10 Years After Sept. 11". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- "Updated Ground Zero Report Examines Failure of Government to Protect Citizens". Sierra Club. 2006. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- Smith, Stephen (April 28, 2008). "9/11 "Wall of Heroes" To Include Sick Cops". CBS News. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- Shukman, David (September 1, 2011). "Toxic dust legacy of 9/11 plagues thousands of people". BBC News. Archived from the original on September 11, 2011. Retrieved September 11, 2011.

Bibliography

- Dwyer, Jim; Flynn, Kevin (2004). 102 Minutes: The Untold Story of the Fight to Survive Inside the Twin Towers. Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-7682-0. OCLC 156884550.

- Corley, G.; Hamburger, R.; McAllister, T. (2002), "Executive Summary", World Trade Center Building Performance Study: Data Collection, Preliminary Observations and Recommendations, Federal Emergency Management Agency, FEMA Report 403, archived from the original on 2013-04-08, retrieved November 25, 2012

- National Institute of Standards and Technology, Technology Administration (2006). "NIST and the World Trade Center". NIST building and fire safety investigation. U.S. Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on January 2, 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2006.