This is the current revision of this page, as edited by Citation bot (talk | contribs) at 01:34, 2 December 2024 (Added issue. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | #UCB_CommandLine). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this version.

Revision as of 01:34, 2 December 2024 by Citation bot (talk | contribs) (Added issue. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | #UCB_CommandLine)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Form of L-carnitine Pharmaceutical compound | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | >10% |

| Elimination half-life | 28.9 - 35.9 hours |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.130.594 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H17NO4 |

| Molar mass | 203.238 g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (what is this?) (verify) | |

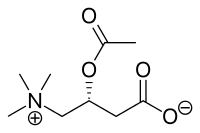

Acetyl-L-carnitine, ALCAR or ALC, is an acetylated form of L-carnitine. It is naturally produced by the human body, and it is available as a dietary supplement. Acetylcarnitine is broken down in the blood by plasma esterases to carnitine which is used by the body to transport fatty acids into the mitochondria for breakdown and energy production.

Biochemical production and action

Carnitine is both a nutrient and made by the body as needed; it serves as a substrate for important reactions in which it accepts and gives up an acyl group. Acetylcarnitine is the most abundant naturally occurring derivative and is formed in the reaction:

- acetyl-CoA + carnitine ⇌ CoA + acetylcarnitine

where the acetyl group displaces the hydrogen atom in the central hydroxyl group of carnitine. Coenzyme A (CoA) plays a key role in the Krebs cycle in mitochondria, which is essential for the production of ATP, which powers many reactions in cells; acetyl-CoA is the primary substrate for the Krebs cycle, once it is de-acetylated, it must be re-charged with an acetyl-group in order for the Krebs cycle to keep working.

Most cell types appear to have transporters to import carnitine and export acyl-carnitines, which seems to be a mechanism to dispose of longer-chain moieties; however many cell types can also import ALCAR.

Within cells, carnitine plays a key role in importing acyl-CoA into mitochondria; the acyl-group of the acyl-CoA is transferred to carnitine, and the acyl-carnitine is imported through both mitochondrial membranes before being transferred to a CoA molecule, which is then beta oxidized to acetyl-CoA. A separate set of enzymes and transporters also plays a buffering role by eliminating acetyl-CoA from inside mitochondria created by the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex that is in excess of its utilization by the Krebs cycle; carnitine accepts the acetyl moiety and becomes ALCAR, which is then transported out of the mitochondria and into the cytosol, leaving free CoA inside the mitochondria ready to accept new import of fatty acid chains. ALCAR in the cytosol can also form a pool of acetyl-groups for CoA, should the cell need it.

Excess acetyl-CoA causes more carbohydrates to be used for energy at the expense of fatty acids. This occurs by different mechanisms inside and outside the mitochondria. ALCAR transport decreases acetyl-CoA inside the mitochondria, but increases it outside.

Health effects

Carnitine and ALCAR supplements carry warnings of a risk that they promote seizures in people with epilepsy, but a 2016 review found this risk to be based only on animal trials.

Research

Reviews

- Peripheral neuropathy: Meta-analyses from 2015 and 2017 both conclude that the current evidence suggests ALC reduces pain from peripheral neuropathy with few adverse effects. The 2017 review also suggested ALC improved electromyographic parameters. Both called for more randomized controlled trials. An updated Cochrane review in 2019 of four studies with 907 participants was very uncertain as to if ALC caused a pain reduction after 6 to 12 months of treatment.

- Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN): A review of two studies concluded that ALC may be a treatment option for paclitaxel- and cisplatin-induced CIPN, while a clinical trial showed it did not prevent CIPN and appeared to worsen the conditions in taxane therapy.

- Male infertility: Scientific reviews from 2016 and 2014 showed mixed results, with some studies showing a positive relationship between ALC and sperm motility, and others showing no relationship.

- Dementia: A 2003 Cochrane review sought to determine the safety and efficacy of ALCAR in dementia but the reviewers found only clinical trials studies on Alzheimer's disease; the review found that the pharmacology of ALCAR was poorly understood and that based on the lack of efficacy, ALCAR was unlikely to be an important treatment for AD.

- Depression: One 2014 review assessed the use of ALCAR in fourteen clinical trials for various conditions with depressive symptoms; the trials were small (ranging from 20 to 193 subjects) and their design was so different that results could not be generalized; most studies showed positive results and a lack of adverse effects. The mechanism of action by which ALCAR could treat depression is not known. A meta-analysis from 2014 concluded that ALCAR could only be recommended for the treatment of persistent depressive disorder if publication bias was deemed improbable. A 2018 systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials found "supplementation significantly decreases depressive symptoms compared with placebo/no intervention, while offering a comparable effect with that of established antidepressant agents with fewer adverse effects." The review also indicates that "the effect of ALC in younger subjects was not more effective than placebo in improving these symptoms." indicating a need for more research explaining the age/effect relation.

- Fragile X syndrome: A 2015 Cochrane review of ALCAR in fragile X syndrome found only two placebo-controlled trials, each of low quality, and concluded that ALCAR is unlikely to improve intellectual functioning or hyperactive behavior in children with this condition.

- Hepatic encephalopathy: ALCAR has been studied in hepatic encephalopathy, a complication of cirrhosis involving neuropsychiatric impairment; ALCAR improves blood ammonia levels and generates a modest improvement in psychometric scores but does not resolve the condition – it may play a minor role in managing the condition.

Studies

- In a small clinical study, when ALCAR was administered intravenously and insulin levels were held steady and a meal low in carnitine but high in carbohydrates was taken by healthy young men, ALCAR appeared to decrease glucose consumption in favor of fat oxidation.

- Mitochondrial decay and oxidative damage to RNA/DNA increases with age in the rat hippocampus, a region of the brain associated with memory. Memory performance declines with age. These increases in decay and damage, and memory loss itself, can be partially reversed in old rats by feeding acetyl-L-carnitine.

References

- Cao Y, Wang YX, Liu CJ, Wang LX, Han ZW, Wang CB (February 2009). "Comparison of pharmacokinetics of L-carnitine, acetyl-L-carnitine and propionyl-L-carnitine after single oral administration of L-carnitine in healthy volunteers". Clinical and Investigative Medicine. 32 (1): E13–E19. doi:10.25011/cim.v32i1.5082. PMID 19178874.

- ^ Bieber LL (1988). "Carnitine". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 57 (1): 261–283. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.001401. PMID 3052273.

- ^ Stephens FB, Constantin-Teodosiu D, Greenhaff PL (June 2007). "New insights concerning the role of carnitine in the regulation of fuel metabolism in skeletal muscle". The Journal of Physiology. 581 (Pt 2): 431–444. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2006.125799. PMC 2075186. PMID 17331998.

- Kiens B (January 2006). "Skeletal muscle lipid metabolism in exercise and insulin resistance". Physiological Reviews. 86 (1): 205–243. doi:10.1152/physrev.00023.2004. PMID 16371598.

- Lopaschuk GD, Gamble J (October 1994). "The 1993 Merck Frosst Award. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase: an important regulator of fatty acid oxidation in the heart". Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 72 (10): 1101–1109. doi:10.1139/y94-156. PMID 7882173.

- Zeiler FA, Sader N, Gillman LM, West M (March 2016). "Levocarnitine induced seizures in patients on valproic acid: A negative systematic review". Seizure. 36: 36–39. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2016.01.020. PMID 26889779.

- Li S, Li Q, Li Y, Li L, Tian H, Sun X (2015-01-01). "Acetyl-L-carnitine in the treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0119479. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019479L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119479. PMC 4353712. PMID 25751285.

- Veronese N (2017). "Effect of acetyl-l-carnitine in the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis". European Geriatric Medicine. 8 (2): 117–122. doi:10.1016/j.eurger.2017.01.002. hdl:10138/235591. S2CID 56342481.

- Rolim LC, da Silva EM, Flumignan RL, Abreu MM, Dib SA (June 2019). "Acetyl-L-carnitine for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (6): CD011265. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011265.pub2. PMC 6953387. PMID 31201734.

- Schloss JM, Colosimo M, Airey C, Masci PP, Linnane AW, Vitetta L (December 2013). "Nutraceuticals and chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN): a systematic review". Clinical Nutrition. 32 (6): 888–893. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2013.04.007. PMID 23647723.

- Brami C, Bao T, Deng G (February 2016). "Natural products and complementary therapies for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 98: 325–334. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.11.014. PMC 4727999. PMID 26652982.

- Ahmadi S, Bashiri R, Ghadiri-Anari A, Nadjarzadeh A (December 2016). "Antioxidant supplements and semen parameters: An evidence based review". International Journal of Reproductive Biomedicine. 14 (12): 729–736. doi:10.29252/ijrm.14.12.729 (inactive 1 November 2024). PMC 5203687. PMID 28066832.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Arcaniolo D, Favilla V, Tiscione D, Pisano F, Bozzini G, Creta M, et al. (September 2014). "Is there a place for nutritional supplements in the treatment of idiopathic male infertility?". Archivio Italiano di Urologia, Andrologia. 86 (3): 164–170. doi:10.4081/aiua.2014.3.164. PMID 25308577.

- Hudson S, Tabet N (2003). "Acetyl-L-carnitine for dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic review). 2003 (2): CD003158. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003158. PMC 6991156. PMID 12804452.

- Wang SM, Han C, Lee SJ, Patkar AA, Masand PS, Pae CU (June 2014). "A review of current evidence for acetyl-l-carnitine in the treatment of depression". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 53: 30–37. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.02.005. PMID 24607292.

- Kriston L, von Wolff A, Westphal A, Hölzel LP, Härter M (August 2014). "Efficacy and acceptability of acute treatments for persistent depressive disorder: a network meta-analysis". Depression and Anxiety. 31 (8): 621–630. doi:10.1002/da.22236. PMID 24448972. S2CID 41163109.

- Veronese N, Stubbs B, Solmi M, Ajnakina O, Carvalho AF, Maggi S (Feb–Mar 2018). "Acetyl-L-Carnitine Supplementation and the Treatment of Depressive Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Psychosomatic Medicine. 80 (2): 154–159. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000537. PMID 29076953. S2CID 7649619.

- Rueda JR, Guillén V, Ballesteros J, Tejada MI, Solà I (May 2015). "L-acetylcarnitine for treating fragile X syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 19 (5): CD010012. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010012.pub2. PMC 10849109. PMID 25985235.

- Jawaro T, Yang A, Dixit D, Bridgeman MB (July 2016). "Management of Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Primer". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 50 (7): 569–577. doi:10.1177/1060028016645826. PMC 1503997. PMID 27126547. S2CID 32765158.

- ^ Liu J, Head E, Gharib AM, Yuan W, Ingersoll RT, Hagen TM, et al. (February 2002). "Memory loss in old rats is associated with brain mitochondrial decay and RNA/DNA oxidation: Partial reversal by feeding acetyl-L-carnitine and/or R -α-lipoic acid". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (4): 2356–2361. doi:10.1073/pnas.261709299. PMC 122369. PMID 11854529.

Further reading

- Jane Higdon, "L-Carnitine", Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University

- Carnitine (L-carnitine), University of Maryland Medical Center

| Antioxidants | |

|---|---|

| Food antioxidants |

|

| Fuel antioxidants | |

| Measurements | |