This is the current revision of this page, as edited by OlEnglish (talk | contribs) at 07:43, 4 December 2024 (→Relevant literature: as per mos:appendix). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this version.

Revision as of 07:43, 4 December 2024 by OlEnglish (talk | contribs) (→Relevant literature: as per mos:appendix)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) 1499 book by Fernando de Rojas For other uses, see La Celestina (disambiguation).| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "La Celestina" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

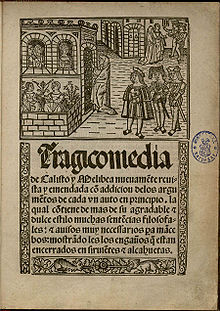

Title page Title page | |

| Author | Fernando de Rojas |

|---|---|

| Original title | Comedia de Calisto y Melibea |

| Language | Spanish |

| Genre | Medieval novel |

| Publisher | Burgos |

| Publication date | 1499 |

| Publication place | Spain |

| Media type | |

The Tragicomedy of Calisto and Melibea (Spanish: Tragicomedia de Calisto y Melibea), known in Spain as La Celestina is a work entirely in dialogue published in 1499. Sometimes called in English The Spanish Bawd, it is attributed to Fernando de Rojas, a descendant of converted Jews, who practiced law and, later in life, served as an alderman of Talavera de la Reina, an important commercial center near Toledo.

The book is considered to be one of the greatest works of all Spanish literature and is even the single topic of a Spanish literary journal, Celestinesca. La Celestina is usually regarded as marking the end of the medieval period and the beginning of the renaissance in Spanish literature. Although usually regarded as a novel, it is written as a continuous series of dialogues and can be taken as a play, having been staged as such and filmed.

The story tells of a bachelor, Calisto, who uses the old procuress and bawd Celestina to start an affair with Melibea, an unmarried girl kept in seclusion by her parents. Though the two use the rhetoric of courtly love, sex — not marriage — is their aim. When he dies in an accident, she commits suicide. The name Celestina has become synonymous with "procuress" in Spanish, especially an older woman used to further an illicit affair, and is a literary archetype of this character, the masculine counterpart being Pandarus.

Plot summary

While chasing his falcon through the fields, a rich young bachelor named Calisto enters a garden where he meets Melibea, the daughter of the house, and is immediately taken with her. Unable to see her again privately, he broods until his servant Sempronio suggests using the old procuress Celestina. She is the owner of a brothel and in charge of her two young employees, Elicia and Areúsa.

When Calisto agrees, Sempronio plots with Celestina to make as much money out of his master as they can. Another servant of Calisto's, Pármeno, mistrusts Celestina because he used to work for her when he was a child. Pármeno warns his master not to use her. However Celestina convinces Pármeno to join her and Sempronio in taking advantage of Calisto. His reward is Areúsa.

As a seller of feminine knick-knacks and quack medicines, Celestina is permitted entrance into the home of Alisa and Melibea by pretending to sell thread. Upon being left alone with Melibea, Celestina tells her of a man in pain who could be cured by the touch of her girdle. When she mentions Calisto's name, Melibea becomes angry and tells her to go. But the crafty Celestina persuades her that Calisto has a horrible toothache that requires her aid, and manages to get the girdle off her and to fix another meeting.

On her second visit, Celestina persuades the now willing Melibea to a rendezvous with Calisto. Upon hearing of the meeting set by Celestina, Calisto rewards the procuress with a valuable gold chain. The lovers arrange to meet in Melibea's garden the following night, while Sempronio and Pármeno keep watch.

When the weary Calisto returns home at dawn to sleep, his two servants go round to Celestina's house to get their share of the gold. She tries to cheat them and in rage they kill her in front of Elicia. After jumping out of the window in an attempt to escape the Night Guard, Sempronio and Pármeno are caught and are beheaded later that day in the town square. Elicia, who knows what happened to Celestina, Sempronio, and Pármeno, tells Areúsa of the deaths. Areúsa and Elicia come up with a plan to punish Calisto and Melibea for being the cause of Celestina, Sempronio, and Pármeno's downfall.

After a month of Calisto sneaking around and seeing Melibea at night in her garden, Areúsa and Elicia enact their plan of revenge. Calisto returns to the garden for another night with Melibea; while hastily leaving because of a ruckus he heard in the street, he falls from the ladder used to scale the high garden wall and dies. After confessing to her father the recent events of her love affair and Calisto's death, Melibea jumps from the tower of the house and dies too.

Historical and social context

La Celestina was written during the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, whose marriage took place in 1469 and lasted until 1504, the year of Isabella's death, which occupies the last phase of the Pre-Renaissance for Spain. Three major events in the history of Spain took place during the union of the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon in 1492. These events were the discovery of the Americas, the conquest of Granada and the expulsion of the Jews. It is also the year that Antonio de Nebrija published the first grammar of the Spanish language, together with Nebrija's own teachings at the University of Salamanca, where Fernando de Rojas studied, favoring the emergence of Renaissance humanism in Spain. Thus, 1492 began the transition between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. It is precisely in the 1490s when the first editions of Comedy of Calisto and Melibea began to appear.

The unification of all the territories of the Iberian Peninsula, except Portugal and the Kingdom of Navarre, under one king and one religion, Catholic Christianity, took place in this period. Claudio Sánchez Albornoz highlighted the importance of being Christian in a society that has warned against members of other religions, such as Jews and Muslims, and even came to outright rejection. Society was suspicious of converts, such as Christians who had been Jews before or had Jewish ancestry, and those who had to hide their conditions. Finally, those of other religions were expelled from the kingdom and the Inquisition would enforce orthodoxy among those who professed the Catholic faith.

Editions

There are two versions of the play. One is called a Comedy and has 16 acts; the other is considered a Tragic Comedy and has 21 acts.

Although most scholars admit that an earlier version by an unknown author already existed, the first known edition is credited to be the Comedy published in Burgos by printer Fadrique de Basilea in 1499. The first page is missing and consequently there is no indication of title or author. It is preserved in the Hispanic Society of New York City. On the first page of the 1500 edition of Toledo, which is for the first time entitled Comedia de Calisto y Melibea, it states: nuevamente revista y enmendada con la adición de los argumentos de cada un auto en principio ("newly reviewed and amended with the addition of the synopses of each act at its beginning"), alluding to a princeps edition prior to 1499.

Some scholars wish to explain this discrepancy about the 1499 date, considering the version published in 1500 in Toledo to be the first edition; however, there is no positive proof of this, and there are some contradictions:

- 1. Acrostic verses are not in themselves proof enough that the 16th century edition is the "Prínceps Edition".

- 2. If the 1499 version was published after the Toledo version, it should contain as stated, additional material, whereas some of the verses are actually omitted.

- 3. The phrase "fernando de royas acabo la comedia" means that a previous version existed and that Fernando de Rojas completed it by adding additional material.

The Toledo 1500 edition contains 16 acts, and also some stanzas with acrostic verses such as "el bachjller fernando de royas acabo la comedia de calysto y melybea y fve nascjdo en la puebla de montalvan", which means "the graduate Fernando de Rojas finished the Comedy of Calisto and Melibea and was born in La Puebla de Montalbán." (This is the reason it is believed that Rojas was the original author of the play.)

A similar edition appeared with minor changes "Comedia de Calisto y Melibea", Sevilla, 1501

A new edition entitled Tragicomedia de Calisto y Melibea (Tragic Comedy of Calisto and Melibea) (Seville: Jacobo Cromberger) appeared in 1502. This version contained 5 additional acts, bringing the total to 21.

Another edition with the title Tragicomedia de Calisto y Melibea (Tragic Comedy of Calisto and Melibea) (Valencia: ) appeared in 1514. This version contained those 5 additional acts, with the total of 21.

In 1526 a version was published in Toledo that included an extra act called the Acto de Traso, named after one of the characters who appears in that act. It became Act XIX of the work, bring the total number of acts to 22. According to the 1965 edition of the play edited by M. Criado de Val and G. D. Trotter, "Its literary value does not have the intensity necessary to grant it a permanent place in the structure of the book, although various ancient editions of the play include it."

The first translation of the work into another language was that by Alfonso Ordoñez into Italian, appearing in 1506. An anonymous translation into French first appeared in 1527 and went through many editions. In 1631, an English translation by James Mabbe, a Fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford, was published under the title The Spanish Bawd.

Characters

Rojas makes a powerful impression with his characters, who appear before the reader full of life and psychological depth; they are human beings with an exceptional indirect characterization, which moves away from the usual archetypes of medieval literature.

Some critics see them as allegories. The literary critic Stephen Gilman has come to deny the possibility of analyzing them as characters, based on the belief that Rojas limited dialogue in which interlocutors respond to a given situation, so that the sociological depth can thus be argued only on extratextual elements.

Lida de Malkiel, another critic, speaks of objectivity, whereby different characters are judged in different manners. Thus, the contradictory behavior of characters would be a result of Rojas humanizing his characters.

One common feature of all of the characters (in the world of nobles as well as servants) is their individualism, their egoism, and their lack of altruism. The theme of greed is explained by Francisco José Herrera in an article about envy in La Celestina and related literature (meaning imitations, continuations, etc.), where he explained the motive of the gossipers and servants to be "greed and robbery", respectively, in the face of the motives of the nobles, which are raging lust and the defense of social and family honor. The private benefit of the lower-class characters forms a substitute for the love/lust present for the upper class.

Fernando de Rojas liked to create characters in pairs, to help build character development through relationships between complementary or opposing characters. In the play in general there are two opposite groups of characters, the servants and the nobles, and within each group are characters divided into pairs: Pármeno and Sempronio, Tristán and Sosia, Elicia and Areúsa, in the group of servants, and Calisto and Melibea, Pleberio and Alisa, in the group of nobles. Only Celestina and Lucrecia do not have a corresponding character, but this is because they perform opposite roles in the plot: Celestina is the element that catalyzes the tragedy, and represents a life lived with wild abandon, while Lucrecia, Melibea's personal servant, represents the other extreme, total oppression. In this sense, the character of the rascal Centurio added in the second version is an addition with little function, although he has something to do with the disorder that calls the attention of Calisto and causes his death.

Celestina

Celestina is the most suggestive character in the work, to the point that she gives it its title. She is a colorful and vivid character, hedonistic, miserly, and yet full of life. She has such a deep understanding of the psychology of the other characters that she can convince even those who do not agree with her plans to accede to them. She uses people's greed, sexual appetite (which she helps create, then provides means to satisfy), and love to control them. She also represents a subversive element in the society, by spreading and facilitating sexual pleasure. She stands apart for her use of magic. Her character is inspired by the meddling characters of the comedies of Plautus and in works of the Middle Ages such as the Libro de Buen Amor (The Book of Good Love) by Juan Ruiz and Italian works like The Tale of Two Lovers by Enea Silvio Piccolomini and Elegía de madonna Fiammeta by Giovanni Boccaccio. She was once a prostitute, and now she dedicates her time to arranging discreet meetings between illicit lovers, and at the same time uses her house as a brothel for the prostitutes Elicia and Areusa.

Melibea

Melibea is a strong-willed girl, in whom repression appears as forced and unnatural; she feels like a slave to the hypocrisy that has existed in her house since her childhood. In the play she appears to be the victim of a strong passion induced by Celestina's spell. She is really bound by her social conscience. She worries about her honor, not modesty, not her concept of what is moral. Her love is more real and less "literary" than that of Calisto: her love motivates her actions, and Celestina's "spell" allows her to retain her honor.

Calisto

A young nobleman who falls madly in love with Melibea. He is shown to be quite egotistical and full of passion as the entire first act is about his love for her. Even going as far as to 'create a new religion' worshipping her (Act 1 pg 92-93). He is also quite insecure as, after he gets rejected, he is easily convinced to go to the witch Celestina for assistance. In the 16-act version, Calisto dies as he falls while climbing down a ladder after a sexual encounter with Melibea.

Sempronio

Servant to Calisto. Sempronio is the one who suggests to Calisto to ask Celestina for help with wooing Melibea; he is also the one who suggests to Celestina that by working together they could swindle money and other items of luxury from Calisto. Sempronio is in love with one of Celestina's prostitutes, Elicia. Through him, we can also see the sexism of how this work represents its day and age. After all, after he and Pármeno kill Celestina he cannot begin to even fathom being betrayed by the women, for the women are now their property.

Pármeno

Servant to Calisto. Son of a prostitute who was friends with Celestina many years ago. As a child, Pármeno worked for Celestina in her brothel doing odd-jobs around the house and the town. Pármeno is in love with the prostitute Areúsa.

Elicia

A prostitute who lives with and works for Celestina. Cousin to Areúsa. Both she and her cousin deeply respect their mistress as they use words such as "Señora" to describe her. It is for this reason that after Sempronio and Pármeno kill Celestina she plots Calisto's death as revenge (and succeeds several months later).

Areúsa

Prostitute who periodically works with Celestina but lives independently. Cousin to Elicia. Both she and her cousin deeply respect their mistress as they use words such as "Señora" to describe her. It is for this reason that after Sempronio and Pármeno kill Celestina she plots Calisto's death as revenge (and succeeds several months later).

Lucrecia

Personal servant to Melibea.

Pleberio

Melibea's father.

Alisa

Melibea's mother.

References

- Lacarra, María Eugenia. "La parodia de la ficción sentimental en la" Celestina"." Celestinesca 13, no. 1 (1989): 11-29.

- Snow, Joseph; Jane Schneider; Cecilia Lee (1976). "Un Cuarto de Siglo de Interes en La Celestina, 1949-75: Documento Bibliografico". Hispania. 59: 610–60. JSTOR 340648.

- celestina in the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- M. Criado de Val y G. D. Trotter, Tragicomedia de Calixto y Melibea, Libro también llamado La Celestina, Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1965 (translation of text on page viii).

- José María Pérez Fernández, ed., James Mabbe, The Spanish Bawd (Modern Humanities Research Association, 2013), "Introduction", pp. 1–66

- In Memoriam: Stephen Gilman (1917–1986), by Constance Rose

Further reading

- Călin, Alin Titi. "Proverbele din La Celestina. De la original la traducere." Philologica Jassyensia 12, no. 2 (34) (2021): 125-133. (English summary)

- Fothergill-Payne, Louise (1988). Seneca and Celestina. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shipley, George A. (1985). "Authority and Experience in La Celestina". Bulettin of Hispanic Studies2 (1): 95-111.

- Webber, Edwin (1957). «The Celestina as an "arte de amores"». Modern Philology (55): 145-153.

External links

- La Celestina -Edition 2008

- La Celestina at Project Gutenberg

- La Celestina in English on Internet Archive