This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Sarcelles (talk | contribs) at 20:37, 20 April 2005 (changed back to the last version of MWAK). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:37, 20 April 2005 by Sarcelles (talk | contribs) (changed back to the last version of MWAK)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between , / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters.error: ISO 639 code is required (help) Dutch is a West Germanic, Low German language spoken worldwide by around 24 million people. The varieties of Dutch spoken in Belgium are also informally called Flemish. The Dutch name for the language is Nederlands or less formal Hollands and Dutch is sometimes called Netherlandic in English. Some speakers resent the name "Dutch", because it is derived from Dietsch (or Diets in modern Dutch), which has the same derivation as Deutsch (German for 'German').

History

The West Germanic dialects can be divided according to tribe (Frisian, Saxon, Franconian, Bavarian and Swabian), and according to the extent of their participation in the Second Germanic sound shift (Low German against High German). The present Dutch standard language is largely derived from Low Franconian dialects spoken in the Low Countries that must have reached a separate identity no later than about AD 700. A process of standardization started in the Middle ages, especially under the influence of the Burgundian Ducal Court in Dijon (Brussels after 1477).

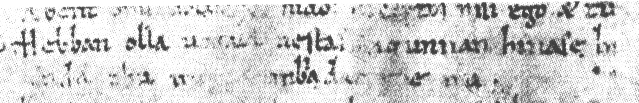

An early Dutch recorded writing is: "Hebban olla vogala nestas hagunnan, hinase hic enda tu, wat unbidan we nu" ("All birds have started making nests, except me and you, what are we waiting for"), dating around the year 1100, written by a Flemish monk in a convent in Rochester (UK). For a long time this sentence was considered to be the earliest in Dutch, but since its discovery even older fragments were found, such as "Visc flot aftar themo uuatare" ("A fish was swimming in the water") and "Gelobistu in got alamehtigan fadaer" ("Do you believe in God the almighty father"). The latter fragment was written as early as 900. Professor Luc De Grauwe from the University of Ghent disputes the language of these stretches of text, and actually believes them to be Old English, so there is still some controversy surrounding them.

The dialects of Flanders and Brabant were the most influential around this time. The process of standardization became much stronger in the 16th century, mainly based on the urban dialect of Antwerp. In 1585 Antwerp fell to the Spanish army: many fled to Holland, strongly influencing the urban dialects of that province. In 1618 a further important step was made towards a unified language, when the first major Dutch bible translation was created that people from all over the United Provinces could understand. It used elements from various (even Low Saxon) dialects, but was mostly based on the urban dialects from Holland.

The word Dutch comes from the old Germanic word theodisk, meaning 'of the people', 'vernacular' as opposed to official, i.e. Latin or later French. Theodisk in modern German has become deutsch and in Dutch has become the two forms: duits, meaning German, and diets meaning something closer to Dutch but no longer in general use (see the diets article).

The English word Dutch has also changed with time. It was only in the early 1600s, with growing cultural contacts and the rise of an independent country, that the modern meaning arose, i.e., 'designating the people of the Netherlands or their language'. Prior to this, the meaning was more general and could refer to any German-speaking area or the languages there (including the current Germany, Austria, and Switzerland as well as the Netherlands). For example:

- William Caxton (c.1422-1491) wrote in his Prologue to his Aeneids in 1490 that an old English text was more like to Dutche than English. In his notes, Professor W.F. Bolton makes clear that this word means German in general rather than Dutch.

- Peter Heylyn, Cosmography in four books containing the Chronography and History of the whole world, Vol. II (London, 1677: 154) contains "...the Dutch call Leibnitz," adding that Dutch is spoken in the parts of Hungary adjoining to Germany.

- To this day, descendants of German settlers in Pennsylvania are known as the "Pennsylvania Dutch".

Classification and related languages

Dutch is grammatically similar in many ways to standard German, but is very different in speech. A speaker of one requires some practice to effectively understand a speaker of the other. Compare, for example:

- De kleinste kameleon is maar 2 cm groot, de grootste kan wel 80 cm worden. (Dutch)

- Das kleinste Chamäleon ist ausgewachsen 2 cm groß, das größte kann gut 80 cm werden.

Some less common phrasings and word choices have closer cognates in German:

- Der kleinste Chamäleon ist nur 2 cm groß, der größte kann wohl 80 cm werden. (less common German)

(Which translates as "The smallest Chameleons are just 2 cm big, the biggest can well achieve 80 cm.")

Above all, Dutch is spoken in a Dutch way, i.e. with its phonetic characteristics which makes it difficult for Germans to understand (and vice versa).

(The same is true for Swiss speaking German in their own way or any other German speaking their dialect)

Strikingly, the differences in the vocabulary between Dutch and German manifest themselves in the short but important structural and everyday words as shown:

| Dutch | German | Translation & Remark |

|---|---|---|

| maar | aber | but |

| slechts, alleen | nur | only |

| misschien | vielleicht | maybe, the Dutch word wellicht resembles the German vielleicht, while the German bisschen resembles the Dutch misschien. |

| graag | gerne | gladly, although see Dutch: gaarne, which means the same but is hardly used |

| gereed, klaar | fertig or bereit | ready - "bereit" is ready and gereed but difficult to discern |

| belangrijk | wichtig | important - although see German: belangreich, which means the same but is hardly used. See also Dutch: gewichtig which means the same, but is rarely used. |

If a German is taught say one or two hundred of these words and a few rules a German will be able to understand written Dutch reasonably well. However, Dutch is not on the curriculum of German schools, except in some border cities, such as Aachen. In Germany, the Low Franconian rural dialects of the Lower Rhine are much closer to Dutch than to standard German.

Even in some places, German and Dutch are spoken almost interchangeably: before mass education began to influence spoken language, on the level of dialects the state border was not a language border - there was a dialect continuum. Dutch speakers are generally able to read German, and German speakers (who can speak English) are generally able to read Dutch, even if they find the spoken language very amusing.

Dutch is (as Low Franconian) a Low German language within the West Germanic branch (see the table above). It is therefore related to other Low Saxon and East Low German languages.

Of all the major modern languages, the closest relative to English is Dutch. However, if minor languages are also considered, then the closest relative to English is Frisian, which is confined mainly within the Dutch province of Friesland.

Geographic distribution

Dutch is spoken in the Netherlands, the northern half of Belgium (Flanders, including Belgium's capital Brussels), the northernmost part of France, the Netherlands Antilles, Aruba, Suriname and amongst certain groups in Indonesia. The last two are former Dutch colonies.

Official status

Dutch is an official language of the Netherlands, Belgium, Suriname, Aruba, and the Netherlands Antilles. The Dutch, Flemish and Surinamese governments coordinate their language activities in the Dutch Language Union (Nederlandse Taalunie).

Algemeen Nederlands (meaning 'general Dutch', abbreviated to AN) is the official Dutch language, the standard language as taught in schools and used by authorities in the Netherlands, Flanders (Belgium), Suriname and the Netherlands Antilles. The Taalunie (Language Union), an association established by Dutch government and the government of Flanders, in 2004 further extended with Surinam, defines what is AN and what is not, e.g. in terms of orthography and spelling.

Prior to the use of Algemeen Nederlands, the term Algemeen Beschaafd Nederlands (general civilized Dutch, abbreviated to ABN) was commonly in use. For reasons of political correctness, the word Beschaafd (civilized) has been left out since this could mean that people who speak variants of Dutch are not civilized. Standaardnederlands (standard Dutch) is also commonly used instead of Algemeen Nederlands.

Dialects

Flemish is the collective term often used for the Dutch dialects spoken in Belgium. It is not a separate language (though the term is often also used to distinguish the standard Dutch spoken in Flanders from that of the Netherlands) nor are the dialects in Belgium more closely related to each other than to the dialects in The Netherlands. The standard form of Netherlandic Dutch differs somewhat from Belgium Dutch or Flemish: Flemish favours older words and is also perceived as "softer" in pronunciation and discourse than Netherlandic Dutch, and some Dutchmen find it quaint. In contrast, Netherlandic Dutch is perceived as harsh and guttural to Belgians, and some Belgians perceive it as overly assertive, hostile and even somewhat arrogant.

In Flanders, there are roughly four dialect groups: West Flemish, East Flemish, Brabantic and Limburgish. They have all incorporated French loanwords in everyday language. An example is fourchette in various forms (originally a French word meaning fork), instead of vork. Brussels, especially, is heavily influenced by French because roughly 75% of the inhabitants of Brussels speak French. The Limburgish in Belgium is closely related to Dutch Limburgish. An oddity of West-Flemish (and to a lesser extent, East-Flemish) is that the pronunciation of the "soft g" sound (the voiced velar fricative) is almost identical to that of the "h" sound (the voiced glottal fricative). Some Flemish dialects are so distinct that they might be considered as separate language variants. West Flemish in particular has sometimes been considered as such. It should also be noted that the dialect borders of these dialects do not correspond to present geopolitical boundaries. They reflect much older medieval divisions. The Brabantic dialect group, for instance, also extends to much of the south of the Netherlands and even into Germany, and so do the dialects of Limburg. West-Flemish is also spoken in the Dutch province of Zeeland and even in a small part of northern France bordering on Belgium near Dunkirk.

The Netherlands also has different dialect regions. In the east there is an extensive Low Saxon dialect area: the provinces of Groningen, Drenthe and Overijssel are almost exclusively Low Saxon. Dutch Limburgish (Limburg (Netherlands)) and Brabantic (Noord-Brabant) fade into the dialects spoken in the adjoining provinces of Belgium. The Zeeuws of most of Zeeland is a form of West Flemish, with the exception of the eastern part of Zeeuws-Vlaanderen where East Flemish is spoken. In Holland proper, Hollandic is spoken, though the original forms of this dialect, heavily influenced by a Frisian substrate, are now rare; the urban dialects of the Randstad, most closely related to Brabantic, do not diverge from standard Dutch very much. Some dialects such as Limburgs and several Low Saxon dialects have been elevated by the European Union to the legal status of streektaal (regional language), which causes some native speakers to consider them separate languages. Some dialects are unintelligible to some speakers of Standard Dutch.

Dutch dialects are not spoken as often as they used to be. Nowadays in The Netherlands only older people speak these dialects in the smaller villages, with the exception of the Low Saxon and Limburgish streektalen, which are actively promoted by some provinces and still in common use. Most towns and cities stick to standard Dutch - although many cities have their own city dialect, which continues to prosper. In Belgium dialects are very much alive however; many senior citizens there are unable to speak standard Dutch. In both the Netherlands and Belgium, many larger cities also have several distinct smaller dialects.

By many native speakers of Dutch, both in Belgium and the Netherlands, Afrikaans and Frisian are often assumed to be very deviant dialects of Dutch. In fact, they are two different languages, Afrikaans having evolved mainly from Dutch. There is no dialect continuum between the Frisian and adjoining Low Saxon dialects. A Frisian standard language has been developed.

Until the early 20th century, variants of Dutch were still spoken by some decendants of Dutch colonies in the United States. New Jersey in particular had an active Dutch community with a highly divergent dialect that was spoken as recently as the 1950s. See Jersey Dutch for more on this dialect.

Accents

In addition to the many dialects of the Dutch language many provinces and larger cities have their own accents, which sometimes are also called dialects. Naturalized migrants also tend to have similar accents: for example many people from the Dutch Antilles or Suriname (regardless of race) speak with a thick "Surinaams" accent, and the Moroccan and Turkish youth have also developed their own accents, which in some cases are enhanced by a debased Dutch slang with Arabic or Turkish words thrown in, which serves in making their speech nearly unintelligible to the Dutch people.

Derived languages

Afrikaans, a language spoken in South Africa and Namibia, is derived primarily from 17th century Dutch dialects, and a great deal of mutual intelligibility still exists.

Sounds

This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between , / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters.Vowels

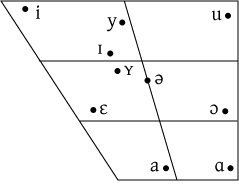

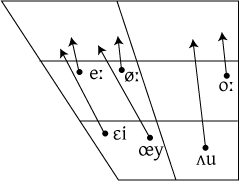

The vowel inventory of Dutch is large, with 13 simple vowels and three diphthongs.

Dutch monophthongs:

Dutch diphthongs:

/eː/, /øː/, /oː/ are included on the diphthong chart because they are actually produced as narrow closing diphthongs in some dialects, but behave phonologically like the other simple vowels.

| Symbol | Example | ||

| IPA | IPA | orthography | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| ] | bɪt | bit | 'bit' |

| i | bit | biet | 'beetroot' |

| ] | hʏt | hut | 'cabin' |

| y | fyt | fuut | 'grebe' |

| ] | bɛt | bed | 'bed' |

| ] | beːt | beet | 'bite' |

| ] | də | de | 'the' |

| ] | nøːs | neus | 'nose' |

| ] | bɑt | bad | 'bath' |

| ] | zaːt | zaad | 'seed' |

| ] | bɔt | bot | 'bone' |

| ] | boːt | boot | 'boat' |

| u | hut | hoed | 'hat' |

| ɛi | ɛi | ei | 'egg' |

| œy | œy | ui | 'onion' |

| ʌu | zʌut | zout | 'salt' |

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

| Plosive | p b | t d | k g | ʔ | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||

| Fricative | f v | s z | ʃ ʒ | x ɣ | ʁ | ɦ | ||

| Approximant | ʋ | j | ||||||

| Lateral | l |

Where symbols for consonants occur in pairs, the left represents the voiceless consonant and the right represents the voiced consonant.

Notes:

1) is not a native phoneme of Dutch and only occurs in borrowed words, like goal.

2) is not a separate phoneme in Dutch, but is inserted before vowel-initial syllables within words after /a/ and /ə/.

3) In some dialects, the voiced fricatives have almost completely merged with the voiceless ones, and is usually realized as , is usually realized as , and is usually realized as .

4) and are not native phonemes of Dutch, and usually occur in borrowed words, like show and bagage (baggage). However, /s/ + /j/ phoneme sequences in Dutch are often realized as , like in the word huisje (='little house'). often is realized as .

5) The realization of the /r/ phoneme varies considerably from dialect to dialect. In the so-called "standard" Dutch of Amsterdam, /r/ is realized as indicated here—as the voiced uvular fricative . In other dialects, however, it is realized as the uvular trill or as the alveolar trill .

6) The "standard" Dutch as spoken in Amsterdam is not the Amsterdams dialect. Amsterdams dialect is different from standard Dutch in that is replaced by in nearly all cases. The standard Dutch is more accurately described as the Dutch that is spoken by most people in Amsterdam, and is the dominating accent used on television.

| Symbol | Example | |||

| IPA | IPA | orthography | English | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | pɛn | pen | 'pen' | |

| b | bit | biet | 'beetroot' | |

| t | tɑk | tak | 'branch' | |

| d | dɑk | dak | 'roof' | |

| k | kɑt | kat | 'cat' | |

| g | gol | goal | 'goal' | |

| m | mɛns | mens | 'human being' | |

| n | nɛk | nek | 'neck' | |

| ] | ɛŋ | eng | 'scary' | |

| f | fits | fiets | 'bicycle' | |

| v | ovən | oven | 'oven' | |

| s | sɔk | sok | 'sock' | |

| z | zep | zeep | 'soap' | |

| ] | ʃɛf | chef | 'boss, chief' | |

| ] | ʒyʁi | jury | 'jury' | |

| x | ɑxt | acht | 'eight' | |

| ] | ɣaːn | gaan | 'to go' | |

| ] | ʁɑt | rat | 'rat' | |

| ] | ɦut | hoed | 'hat' | |

| ] | ʋɑŋ | wang | 'cheek' | |

| j | jɑs | jas | 'coat' | |

| l | lɑnt | land | 'land' | |

| ] | bəʔɑmə | beamen | 'confirm' | |

Phonology

Dutch devoices all consonants at the ends of words (e.g. a final d sound becomes a t sound; to become 'ents of worts'), which presents a problem for Dutch speakers when learning English.

Because of assimilation, often the initial consonant of the next word is also devoiced, e.g. het vee (the cattle) is /hətfe/. This process of devoicing is taken to an extreme in some regions (Amsterdam, Friesland) with almost complete loss of /v/,/z/ and /ɣ/. Further south these phonemes are certainly present in the middle of a word. Compare e.g. logen and loochen /loɣə/ vs. /loxə/. In Flanders the contrast is even greater because the g becomes a palatal. ('soft g').

The final 'n' of the plural ending -en is often not pronounced (as in Afrikaans), except in the North East and the South West where the ending becomes a syllabic n sound.

Historical sound changes

Dutch (with the exception of the Limburg dialects) did not participate in the second (High German) sound shifting - compare German machen /-x-/ Dutch maken, English make,

German Pfanne /pf-/, Dutch pan, English pan, German zwei /ts-/, Dutch twee, English two.

It also underwent a few changes of its own. For example, words in -old or -olt lost the l in favor of a diphthong. Compare English old, German alt, Dutch oud. A word like hus with /u/ (English "house") first changed to huus with /y/, then finally to huis with a diphthong that resembles the one in French l'oeil. The phoneme /g/ was lost in favor of a (voiced) velar fricative /ɣ/, or a voiced palatal fricative (in the South: Flanders, Limburg).

Grammar

- Main article: Dutch grammar

Like all other continental West Germanic languages, Dutch has a rather complicated word order that is markedly different from English, which presents a problem for Anglophones learning Dutch. Dutch, like German and Norwegian, is also known for its ability to glue words together to form very long words. Examples of this are de randjongerenhangplekkenbeleidsambtenarensalarisbesprekingsafspraken listen (the agreements for the negotiations concerning the salary of public servants who decide on the policy for areas where unemployed youth is allowed to hang out), hottentottententententoonstellingsmakersopleidingsprogramma listen (the curriculum of an education teaching the makers of exhibitions about the tents of the Hottentots), and a number with dozens of digits can be written out as one word. Though grammatically correct, it is never done to this extent; at most two or three words are glued together.

The Dutch written grammar has simplified a lot over the past 100 years: cases are now only used for the pronouns (for example: ik = I, me = me, mij = me, mijn = my, wie = who, wiens = whose, wier = whose). Nouns and adjectives are not case inflected (except for the genitive of nouns: -(')s or -'). In the spoken language cases and case inflections had already gradually disappeared from a much earlier date on (probably the 15th century) as in all continental West Germanic dialects.

Inflection of adjectives is a little more complicated: nothing with indefinite (een "a", "an"...), neuter nouns in singular and -e in all other cases.

- een mooi huis (a beautiful house)

- het mooie huis (the beautiful house)

- mooie huizen (beautiful houses)

- de mooie huizen (the beautiful houses)

- een mooie vrouw (a beautiful woman)

More complex inflection is still used in certain expressions like de heer des huizes (litt.: the man of the house), ter hulp komen (to come to help), etc. These are usually remnants of cases and other inflections no longer in general use today.

Dutch nouns are, however, inflected for size: -je for singular diminuitive and -jes for plural diminuitive. Between these suffixes and the radical can come extra letters depending on the ending of the word:

- boom (tree) - boompje

- ring (ring) - ringetje

- koning (king) - koninkje

- tien (ten) - tientje

Vocabulary

- See the list of Dutch words and list of words of Dutch origin at Wiktionary, the free dictionary and Misplaced Pages's sibling project

Dutch has more French loanwords than German, but fewer than English. The number of English loanwords in Dutch is quite large, and is growing rapidly. In fact, when a speaker uses too many words or expressions of English origin, he is said to be suffering from the 'English disease' (Engelse ziekte). New loanwords are almost never pronounced as the original English word, or are spelled differently. Dutch also has a lot of Greek and Latin loanwords. There are also some German loanwords, like überhaupt and sowieso. Even though few true loanwords are present, German has had a profound effect upon the lexicon of the language, done mainly by taking German words and just changing them into words that seem Dutch (so called germanisme), a process probably to be ascribed to the likeness of the two languages. Some of these forms have become so integral to Dutch that few Dutch notice it; they include words like opname (from German Aufname), aanstalten (Anstalten) and many more.

Writing system

Dutch is written using the Latin alphabet, see Dutch alphabet. The diaeresis is used to mark vowels that are pronounced separately, and called trema. In the most recent spelling reform, a hyphen has replaced the trema in a few words where it had been previously used: zeeëend (seaduck) is now spelled zee-eend. The acute accent (accent aigu) occurs mainly on loanwords like café, but can also be used for emphasis or to differentiate between two forms. Its most common use is to differentiate between the indefinite article 'een' (a, an) and the numeral 'één' (one). The grave accent (accent grave) is used to clarify pronunciation ('hè' (what?, what the ...?), 'appèl' (call for), 'bèta') and in loanwords ('caissière' (cashier), 'après-ski'). In the recent spelling reform, the accent grave was dropped as stress sign on short vowels in favour of the accent aigu (e.g. 'wèl' was changed to 'wél'). Other diacritical marks such as the circumflex only occur on a few words, most of them loanwords from French.

The most important dictionary of the modern Dutch language is the Van Dale groot woordenboek der Nederlandse taal, more commonly referred to as the Dikke van Dale ("dik" is Dutch for "fat" or "thick"), or as linguists nicknamed it: De Vandaal (the vandal). However, it is dwarfed by the "Woordenboek der Nederlandsche taal", a scholarly endeavour that took 147 years from initial idea to first edition, resulting in over 45,000 pages.

The semi-official spelling is given by the Woordenlijst Nederlandse taal, more commonly known as "het groene boekje" (i.e. "the green booklet", because of its colour.)

See also

- Bargoens

- Common phrases in different languages

- Dutch grammar

- Dutchism - Dutch loanwords in English

- Gezellig -- One of the ten non-English words that were voted "words hardest to translate" in June 2004 by a British translation company.

- Limburgian dialect

- List of languages

Dutch literature

see Dutch literature

External links

- A Dutch course at Wikibooks

- Online Nederlands leren

- History of the Dutch Language

- Nederlandse Taalunie (Dutch Language Union -- in Dutch)

- Dutch for Beginners (Introduction to Dutch grammar and vocabulary)

- Algemene Nederlandse Spraakkunst (General Dutch Grammar -- in Dutch)

- Online Dutch Grammar Course (Dutch Grammar -- in English)

- Free online resources for learners

- Dutch Course in 8 Chapters

- Ethnologue report for Dutch

- Euromosaic - Flemish in France - The status of Dutch in France

- Sampa for Dutch

- List of online Dutch-related resources

Dictionaries

- All Dutch free dictionaries

- Online Nederlands Woordenboek

- Majstro Dutch-English-Dutch Online Dictionary

- Lookwayup English-Dutch-English dictionary

- Freedict English-Dutch-English dictionary

- Travlang Dutch-English dictionary

- Euroglot dictionary

- Van Dale (Dictionary -- in Dutch)

- http://www.notam02.no/~hcholm/altlang/ht/Dutch.html - The Alternative Dutch Dictionary

- Flemish - English Dictionary: from Webster's Online Dictionary - the Rosetta Edition.

- Dutch - English Dictionary: from Webster's Online Dictionary - the Rosetta Edition.

- A dictionary of Organic Chemistry (in Dutch)