This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Acdixon (talk | contribs) at 22:42, 26 June 2007 (→Formation: expansion with cites). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:42, 26 June 2007 by Acdixon (talk | contribs) (→Formation: expansion with cites)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

The Confederate government of Kentucky was a shadow government established for the Commonwealth by Southern sympathizers during the American Civil War. While it never replaced the elected government in Frankfort, the provisional government was recognized by the Confederate States of America. Kentucky was admitted to the Confederacy on December 10, 1861.

Bowling Green was designated the Confederate capital of Kentucky, but due to the military situation in the state, the provisional government traveled with the Army of Tennessee for most of its existence. For a short time in the autumn of 1862, the Confederate Army controlled Frankfort, the only time a Union capital was captured by Confederate forces. During this occupation, General Braxton Bragg attempted to install the provisional government as the permanent authority in the Commonwealth. However, Union General Don Carlos Buell ambushed the inauguration ceremony and drove the provisional government from the state for the final time. From that point forward, the government existed primarily on paper, and was dissolved at the end of the war.

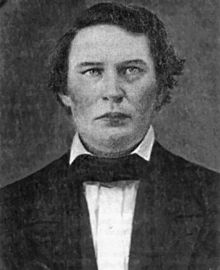

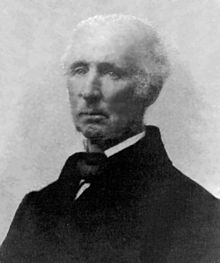

The provisional government elected two governors. George W. Johnson was elected at the Russellville Convention and served until his death at the Battle of Shiloh. Richard Hawes was elected to replace Johnson, and served through the remainder of the war.

Formation

The origins of the movement to create a Confederate government for Kentucky remains unknown. The inspiration may have been derived from the actions of Missouri Confederates in forming a shadow government for their state. Whatever the case, it is known that at the forefront of the movement were former Vice President John C. Breckinridge and Scott County farmer George W. Johnson. In his October 8, 1861 "Address to the People of Kentucky," Breckinridge declared "The United States no longer exists. The Union is dissolved."

On October 29, 1861, 63 delegates representing 34 counties met at Russellville, Kentucky to discuss the formation of a Confederate government for the Commonwealth, believing the Unionist government in Frankfort did not represent the will of the majority of Kentucky's citizens. Trigg County's Henry Burnett was elected chairman of the proceedings. George Johnson chaired the committee that authored the convention's final report, and introduced some of its key resolutions. The report called for a sovereignty convention to sever ties with the Federal government. Both Breckinridge and Johnson served on the Committee of Ten that made arrangements for the convention.

On November 18, 1861, 116 delegates from 68 counties met at the Clark House in Russellville. Burnett was again elected presiding officer, and fearing for the safety of the delegates, initially proposed postponing the proceedings until January 8, 1862. Johnson convinced the majority of the delegates to continue, working behind closed doors, but by the third day, the military situation was so tenuous that the entire convention had to be moved to a tower on the campus of Bethel College, a now-defunct institution in Russellville.

| Position | Officeholder |

|---|---|

| Governor | George W. Johnson |

| Lieutenant Governor | Horatio F. Simrall |

| Secretary of State | Robert McKee |

| Treasurer | Theodore Legrand Burnett |

| Auditor | Josiah Pillsbury |

The first item of business was the ratification of an ordinance of secession, which proceeded in short order. Next, being unable to flesh out a complete constitution and system of laws, the delegates voted that "the Constitution and laws of Kentucky, not inconsistent with the acts of this Convention, and the establishment of this Government, and the laws which may be enacted by the Governor and Council, shall be the laws of this state." The provisional government proposed by the delegates consisted of a legislative council of ten members (one from each Kentucky congressional district) and a governor, who had the power to appoint judicial and other officials, a treasurer and an auditor. The delegates designated Bowling Green (then under the control of Confederate general Albert Sidney Johnston) as the Confederate State capital, but had the foresight to provide that the government could meet anywhere deemed appropriate by the council and governor. The convention adopted a new state seal, an arm wearing mail with a star, extended from a circle of twelve other stars.

The convention unanimously elected Johnson as governor. There is also some indication that Horatio F. Simrall was elected lieutenant governor, but soon fled to Mississippi to escape Federal authorities. Robert McKee, who had served as secretary of both conventions, was elected secretary of state. Theodore Legrand Burnett was elected treasurer, but resigned on December 17 to accept a position in the Confederate Congress. He was replaced by Warren County native John Quincy Burnham. The position of auditor was first offered to former Congressman Richard Hawes, but Hawes declined in order to continue his military service under Humphrey Marshall. In his stead, the convention elected Josiah Pillsbury, also of Warren County.

On November 21, the day following the convention, Johnson wrote Confederate president Jefferson Davis to request Kentucky's admission to the Confederacy. Burnett, William Preston, and William E. Simms were chosen as the state's commissioners to the Confederacy. For reasons unexplained by the delegates, Dr. Luke P. Blackburn, a native Kentuckian living in Mississippi, was invited to accompany the commissioners to Richmond. Though Davis had some reservation about the circumvention of the elected General Assembly in forming the Confederate government, he concluded that Johnson's request had merit. Kentucky was admitted to the Confederacy on December 10, 1861.

Activity

On November 26, 1861, Governor Johnson issued an address to the citizens of the Commonwealth blaming abolitionists for the breakup of the United States. He asserted his belief that the Union and Confederacy were forces of equal strength, and that the only solution to the war was a free trade agreement between the two sovereign nations. He further announced his willingness to resign as provisional governor if the Kentucky General Assembly, which was overwhelmingly Unionist, would agree to cooperate with elected governor Beriah Magoffin, a Southern sympathizer. Magoffin himself denounced the Russellville Convention and the provisional government, stressing the need to abide by the will of the majority of the Commonwealth's citizens.

During the winter of 1861, Johnson tried mightily to assert the legitimacy of the fledgling government, but to no avail. Its jurisdiction extended only as far as the area controlled by the Confederate Army. Johnson came woefully short of raising the 46,000 troops requested by the Confederate Congress in Richmond. Efforts to levy taxes and to compel citizens to turn over their guns to the government were similarly unsuccessful. On January 3, 1862, Johnson requested a sum of $3 million from the Confederate Congress to meet the provisional government's operating expenses. The Congress instead approved a sum of $2 million, the expenditure of which required approval of Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin and President Davis. Much of the provisional government's operating capital was probably provided by Kentucky congressman Eli Metcalfe Bruce, who made a fortune from varied economic activities throughout the war.

Governor Johnson and the legislative council set election day for Confederate Kentucky on January 22, 1862. In this election, the provisional ten-man legislative council was to be replaced by a permanent congress. Under the rules determined by the Confederate Congress, Kentucky was entitled to two senators and 12 representatives. Voters were allowed to vote in whichever county they occupied on election day, and could cast a general ballot for all positions. In an election that saw military votes outnumber civilian ones, only four of the original legislative council members were elected to seats in the Confederate House of Representatives. One of the original council, Burnett, was elected to the Confederate Senate. Local officials were appointed in areas controlled by Confederate forces, including many justices of the peace. When the Confederate government was disbanded, the legality of marriages performed by these justices was questioned, but eventually upheld.

Withdrawal from Kentucky and death of Governor Johnson

Following Ulysses S. Grant's victory at the Battle of Fort Henry, General Johnston withdrew from Bowling Green into Tennessee on February 7, 1862. A week later, Governor Johnson and the provisional government followed. On March 12, a New Orleans newspaper reported that "the capital of Kentucky now being located in a Sibley tent."

Governor Johnson, despite his age (50) and a crippled arm, volunteered to serve under General John C. Breckinridge and Colonel Robert P. Trabue at the Battle of Shiloh. On April 7, 1862, Johnson was severely wounded in the thigh and abdomen, and lay on the battlefield until the following day. Johnson was recognized by acquaintance and fellow Freemason, Alexander McDowell McCook, a Union general. Despite the ministrations of several physicians, Johnson died aboard the Union hospital ship Hannibal, and the provisional government of Kentucky was left leaderless.

Richard Hawes as governor

Prior to the abandonment of Bowling Green, Governor Johnson had requested that Richard Hawes come to the city and help with the administration of the government, but Hawes was delayed due to a bout with typhoid fever. Following Johnson's death, the provisional government elected Hawes, who was still recovering from his illness, as governor. He joined the government in Tennessee in the spring of 1862, and took the oath of office on May 31.

On August 27, Hawes was dispatched to Richmond, Virginia to favorably recommend Braxton Bragg's planned invasion of Kentucky to President Davis, but Davis was non-committal. Bragg proceeded, nonetheless, while the leaders of Kentucky's Confederate government remained in Chattanooga, awaiting Hawes' return. They departed on September 18, and caught up with Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith in Lexington, Kentucky on October 2.

Bragg, desiring to enforce the Confederate Conscription Act in the Commonwealth, decided to install the provisional government in the recently-captured state capital of Frankfort. On October 4, 1862, Hawes was inaugurated as governor by the Confederate legislative council. In the celebratory atmosphere of the inauguration ceremony, the Confederate forces let their guard down, and were ambushed and forced to retreat by Union General Don Carlos Buell.

Decline and dissolution

Following the drawn Battle of Perryville, the provisional government left Kentucky for the final time. Continuing to travel with the Army of Tennessee, Hawes and the other Confederate officials futilely attempted to carry out the duties of their respective offices and unsuccessfully lobbied President Davis to attempt another foray into the Commonwealth. Another major blow was Davis' decision not to allow Hawes to spend $1 million that had been secretly appropriated in August of 1861 to help Kentucky maintain its neutrality. Davis reasoned that the money could not be spent for its intended purpose, since Kentucky was now a part of the Confederacy.

Late in the war, the provisional government existed mostly on paper. However, in the summer of 1864, Colonel R. A. Alston of the Ninth Tennessee Cavalry requested Governor Hawes' assistance in investigating crimes allegedly committed by General John Hunt Morgan during his unauthorized raid into Kentucky. Hawes never had to act on the request, however, as Morgan was suspended from command on August 10 and killed by Union troops on September 4, 1864.

There is no documentation detailing exactly when Kentucky's provisional government ceased operation. It is assumed to have dissolved upon the conclusion of the Civil War.

See also

References

- ^ Kent Masterson Brown, ed. (2000). "The Government of Confederate Kentucky". The Civil War in Kentucky: Battle for the Bluegrass. Mason City, Iowa: Savas Publishing Company. pp. pp. 69–98. ISBN 1882810473.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Lowell H. Harrison, ed. (2004). "George W. Johnson". Kentucky's Governors. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. pp. pp. 82–84. ISBN 0813123267.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Kleber, John E., ed. (1992). "Confederate State Government". The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. pp. p. 222. ISBN 0813117720.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Cantrell, Doug (2005). "George W. Johnson and Richard Hawes: The Governors of Confederate Kentucky". Kentucky Through the Centuries: A Collection of Documents & Essays. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. pp. pp. 159–184. ISBN 075752012X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Powell, Robert A. (1976). "Confederate State of Kentucky: Provisional Governors". Kentucky Governors. Frankfort, Kentucky: Kentucky Images. pp. p. 114. ISBN B0006CPOVM.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) Cite error: The named reference "powell-simrall" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - Per The Kentucky Encyclopedia, this position was first offered to Richard Hawes, who declined it.

- Kleber, John E., ed. (1992). "Hawes, Richard". The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. pp. p. 418–419. ISBN 0813117720.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Jerlene Rose, ed. (2005). "George W. Johnson, Governor of Confederate Kentucky". Kentucky's Civil War 1861 – 1865. Clay City, Kentucky: Back Home in Kentucky, Inc. pp. pp. 63–65. ISBN 0976923122.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Kleber, John E., ed. (1992). "Johnson, George W.". The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. pp. p. 473. ISBN 0813117720.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Jerlene Rose, ed. (2005). "Richard Hawes, 1797–1877: Our Cause is Steadily on the Increase". Kentucky's Civil War 1861 – 1865. Clay City, Kentucky: Back Home in Kentucky, Inc. pp. pp. 90–91. ISBN 0976923122.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Lowell H. Harrison, ed. (2004). "Richard Hawes". Kentucky's Governors. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. pp. pp. 85–88. ISBN 0813123267.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Powell, Robert A. (1976). "Richard Hawes". Kentucky Governors. Danville, Kentucky: Bluegrass Printing Company. pp. p. 115. ISBN B0006CPOVM.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help)

External links

- Text of Kentucky's ordinance of secession

- Secession and the Union in Tennessee and Kentucky: A Comparitive Analysis James Copeland, Walters State Community College