This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 216.85.191.26 (talk) at 16:25, 31 August 2007 (→Biography). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:25, 31 August 2007 by 216.85.191.26 (talk) (→Biography)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Leo Tolstoy | |

|---|---|

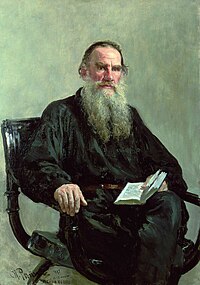

Leo Tolstoy, late in life. Leo Tolstoy, late in life. | |

| Born | (1828-08-28)August 28, 1828 Yasnaya Polyana, |

| Died | (1910-11-20)November 20, 1910 Astapovo, |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Genre | Realist |

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy(Lyof, Lyoff) (September 9 [O.S. August 28] 1828 – November 20 [O.S. November 7] 1910) (Template:Lang-ru, IPA: listen), commonly referred to in English as Leo Tolstoy, was a Russian writer – novelist, essayist, dramatist and philosopher – as well as pacifist Christian anarchist and educational reformer. He is perhaps the most influential member of the aristocratic Tolstoy family.

As a fiction writer Tolstoy is widely regarded as one of the greatest of all novelists, particularly noted for his masterpieces War and Peace and Anna Karenina. In their scope, breadth and realistic depiction of 19th-century Russian life, the two books stand at the peak of realist fiction. As a moral philosopher Tolstoy was notable for his ideas on nonviolent resistance through works such as The Kingdom of God is Within You, which in turn influenced such twentieth-century figures as Mohandas K. Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr.

\

Novels and fictional works

Tolstoy's fiction consistently attempts to convey realistically the Russian society in which he lived. Matthew Arnold commented that Tolstoy's work is not art, but a piece of life. Arnold's assessment was echoed by Isaak Babel who said that, "if the world could write by itself, it would write like Tolstoy".

His first publications were three autobiographical novels, Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth (1852 – 1856). They tell of a rich landowner's son and his slow realization of the differences between him and his peasants. Although in later life Tolstoy rejected these books as sentimental, a great deal of his own life is revealed, and the books still have relevance for their telling of the universal story of growing up.

Tolstoy served as a second lieutenant in an artillery regiment during the Crimean War, recounted in his Sevastapol Sketches. His experiences in battle helped develop his pacifism, and gave him material for realistic depiction of the horrors of war in his later work.

The Cossacks (1863) is an unfinished novel which describes the Cossack life and people through a story of Dmitri Olenin, a Russian aristocrat in love with a Cossack girl. This text was acclaimed by Ivan Bunin as one of the finest in the language. The magic of Tolstoy's language is naturally lost in translation, but the following excerpt may give some idea as to the lush, sensuous, pulsing texture of the original:

Along the surface of the water floated black shadows, in which the experienced eyes of the Cossack detected trees carried down by the current. Only very rarely sheet-lightning, mirrored in the water as in a black glass, disclosed the sloping bank opposite. The rhythmic sounds of night — the rustling of the reeds, the snoring of the Cossacks, the hum of mosquitoes, and the rushing water, were every now and then broken by a shot fired in the distance, or by the gurgling of water when a piece of bank slipped down, the splash of a big fish, or the crashing of an animal breaking through the thick undergrowth in the wood. Once an owl flew past along the Terek, flapping one wing against the other rhythmically at every second beat.

War and Peace is generally thought to be one of the greatest novels ever written, remarkable for its breadth and unity. Its vast canvas includes 580 characters, many historical, others fictional. The story moves from family life to the headquarters of Napoleon, from the court of Alexander I of Russia to the battlefields of Austerlitz and Borodino. The novel explores Tolstoy's theory of history, and in particular the insignificance of individuals such as Napoleon and Alexander. But more importantly, Tolstoy's imagination created a world that seems to be so believable, so real, that it is not easy to realize that Tolstoy never actually witnessed the epoch described in the novel.

Somewhat surprisingly, Tolstoy did not consider War and Peace to be a novel (nor did he consider many of the great Russian fictions written at that time to be novels). It was to him an epic in prose. Anna Karenina (1877), which Tolstoy regarded as his first true novel, was one of his most impeccably constructed and compositionally sophisticated works. It tells parallel stories of an adulterous woman trapped by the conventions and falsities of society and of a philosophical landowner (much like Tolstoy) who works alongside the peasants in the fields and seeks to reform their lives. His last novel was Resurrection, published in 1899, which told the story of a nobleman seeking redemption for a sin committed years earlier and incorporated many of Tolstoy's refashioned views on life. An additional short novel, Hadji Murat, was published posthumously in 1912.

Tolstoy's later work is often criticised as being overly didactic and patchily written, but derives a passion and verve from the depth of his austere moral views. His short story Family Happiness explores the feelings of arranged marriage. Gorky relates how Tolstoy once read a passage from Father Sergius before himself and Chekhov and that Tolstoy was moved to tears by the end of the reading. Other later passages of rare power include the crises of self faced by the protagonists of After the Ball and Master and Man, where the main character (in After the Ball) or the reader (in Master and Man) is made aware of the foolishness of the protagonists' lives. The Death of Ivan Ilyich is perhaps the greatest fictional meditation on death ever written.

Tolstoy had an abiding interest in children and children's literature and wrote tales and fables. Some of his fables are free adaptations of fables from Aesop and from Hindu tradition.

Reputation

Tolstoy's contemporaries paid him lofty tributes: Fyodor Dostoyevsky thought him the greatest of all living writers and Gustave Flaubert, on reading War and Peace for the first time in translation, compared him to Shakespeare and gushed: "What an artist and what a psychologist!". Ivan Turgenev called Tolstoy a "great writer of the Russian land" and implored him not to abandon literature on his deathbed. Anton Chekhov, who often visited Tolstoy at his country estate, wrote: "When literature possesses a Tolstoy, it is easy and pleasant to be a writer; even when you know you have achieved nothing yourself and are still achieving nothing, this is not as terrible as it might otherwise be, because Tolstoy achieves for everyone. What he does serves to justify all the hopes and aspirations invested in literature."

Later critics and novelists continue to bear testaments to his art: Virginia Woolf went on to declare him "greatest of all novelists", and James Joyce, defending him from criticism, noted: "He is never dull, never stupid, never tired, never pedantic, never theatrical". Thomas Mann wrote of his seemingly guileless artistry — "Seldom did art work so much like nature" — sentiments shared in part by many others, including Marcel Proust and William Faulkner. Vladimir Nabokov, himself a Russian and an infamously harsh critic, placed him above all other Russian fiction writers, even Gogol, and equalled him with Pushkin among Russian writers.

Religious and political beliefs

At approximately the age of 50, Tolstoy experienced a spiritual crisis, at which point he was so agonized about discovering life's meaning as to seriously contemplate ending his life. He relates the story of this spiritual crisis in A Confession, and the conclusions of his studies in My Religion, The Kingdom of God is Within You and The Gospels in Brief.

After reading Schopenhauer's The World as Will and Representation, Tolstoy gradually became converted to the ascetic morality that was praised in that book.

Do you know what this summer has meant for me? Constant raptures over Schopenhauer and a whole series of spiritual delights which I've never experienced before. ... no student has ever studied so much on his course, and learned so much, as I have this summer.

— Tolstoy's Letter to A.A. Fet, August 30, 1869

In Chapter VI of A Confession, Tolstoy quoted the final paragraph of Schopenhauer's work. In this paragraph, the German philosopher explained how the nothingness that results from complete denial of self is only a relative nothingness and not to be feared. Tolstoy was struck by the description of Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu ascetic renunciation as being the path to holiness. After reading passages such as the following, which abound in Schopenhauer's ethical chapters, Tolstoy, the Russian nobleman, chose poverty and denial of the will.

But this very necessity of involuntary suffering (by poor people) for eternal salvation is also expressed by that utterance of the Savior (Matthew 19:24): "It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God." Therefore those who were greatly in earnest about their eternal salvation, chose voluntary poverty when fate had denied this to them and they had been born in wealth. Thus Buddha Sakyamuni was born a prince, but voluntarily took to the mendicant's staff; and Francis of Assisi, the founder of the mendicant orders who, as a youngster at a ball, where the daughters of all the notabilities were sitting together, was asked: "Now Francis, will you not soon make your choice from these beauties?" and who replied: "I have made a far more beautiful choice!" "Whom?" "La poverta (poverty)": whereupon he abandoned every thing shortly afterwards and wandered through the land as a mendicant.

— Schopenhauer, Parerga and Paralipomena, Vol. II, §170

The teaching of mature Tolstoy is a rationalized "Christianity", stripped of all tradition and all positive mysticism. He rejected personal immortality and concentrated exclusively on the moral teaching of the Gospels. Tolstoy's Christian beliefs were based on the Sermon on the Mount, and particularly on the phrase "turn the other cheek", which he saw as a justification for pacifism, nonviolence and nonresistance. Of the moral teaching of Christ, the words "Resist not evil" were taken to be the principle out of which all the rest follows. He condemned the State, which sanctioned violence and corruption, and rejected the authority of the Church, which sanctioned the State. His condemnation of every form of compulsion authorizes many to classify Tolstoy's later teachings, in its political aspect, as Christian anarchism.

Sources

Tolstoy's conversion from a dissolute and privileged society author to the non-violent and spiritual anarchist of his latter days was brought about by two trips around Europe in 1857 and 1860-61, a period when many liberal-leaning Russian aristocrats escaped the stifling political repression in Russia; others who followed the same path were Alexander Herzen, Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin. During his 1857 visit, Tolstoy witnessed a public execution in Paris, a traumatic experience that would mark the rest of his life. Writing in a letter to his friend V. P. Botkin:

The truth is that the State is a conspiracy designed not only to exploit, but above all to corrupt its citizens ... Henceforth, I shall never serve any government anywhere.

Tolstoy's political philosophy was also influenced by a March 1861 visit to French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, then living in exile under an assumed name in Brussels. Apart from reviewing Proudhon's forthcoming publication, "La Guerre et la Paix", whose title Tolstoy would borrow for his masterpiece, the two men discussed education, as Tolstoy wrote in his educational notebooks:

If I recount this conversation with Proudhon, it is to show that, in my personal experience, he was the only man who understood the significance of education and of the printing press in our time.

Tolstoy's belief in non-violence has been strongly influenced by 15th century Czech rebelious scholar Petr Chelčický .

Christian anarchism

Although he did not call himself an anarchist because he applied the term to those who wanted to change society through violence, Tolstoy is commonly regarded as an anarchist. Tolstoy believed being a Christian made him a pacifist and, due to the military force used by government, being a pacifist made him an anarchist.

Tolstoy's doctrine of nonresistance (nonviolence) when faced by conflict is another distinct attribute of his philosophy based on Christ's teachings. By directly influencing Mahatma Gandhi with this idea through his work The Kingdom of God is Within You, Tolstoy has had a huge influence on the nonviolent resistance movement to this day. He opposed private property and the institution of marriage and valued the ideals of chastity and sexual abstinence (as discussed in Father Sergius and his preface to The Kreutzer Sonata), ideals also held by the young Gandhi.

In hundreds of essays over the last twenty years of his life, Tolstoy reiterated the anarchist critique of the State and recommended books by Kropotkin and Proudhon to his readers, whilst rejecting anarchism's espousal of violent revolutionary means, writing in the 1900 essay, "On Anarchy":

The Anarchists are right in everything; in the negation of the existing order, and in the assertion that, without Authority, there could not be worse violence than that of Authority under existing conditions. They are mistaken only in thinking that Anarchy can be instituted by a revolution. But it will be instituted only by there being more and more people who do not require the protection of governmental power ... There can be only one permanent revolution - a moral one: the regeneration of the inner man.

Pacifism

Despite his misgivings about anarchist violence, Tolstoy took risks to circulate the prohibited publications of anarchist thinkers in Russia, and corrected the proofs of Peter Kropotkin's "Words of a Rebel", illegally published in St Petersburg in 1906. Two years earlier, during the Russo-Japanese War, Tolstoy publicly condemned the war and wrote to the Japanese Buddhist priest Soyen Shaku in a failed attempt to make a joint pacifist statement.

A letter Tolstoy wrote in 1908 to an Indian newspaper entitled "Letter to a Hindu" resulted in intense correspondence with Mohandas Gandhi, who was in South Africa at the time and was beginning to become an activist. Reading "The Kingdom of God is Within You" had convinced Gandhi to abandon violence and espouse nonviolent resistance, a debt Gandhi acknowledged in his autobiography, calling Tolstoy "the greatest apostle of non-violence that the present age has produced". The correspondence between Tolstoy and Gandhi would only last a year, from October 1909 until Tolstoy's death in November 1910, but led Gandhi to give the name the Tolstoy Colony to his second ashram in South Africa. Besides non-violent resistance, the two men shared a common belief in the merits of vegetarianism, the subject of several of Tolstoy's essays (see Christian vegetarianism). According to V.S. Naipaul Tolstoy had also criticised Gandhi for his politics by saying that "...his Hindu nationalism destroys everything"

Along with his growing idealism, Tolstoy also became a major supporter of the Esperanto movement. Tolstoy was impressed by the pacifist beliefs of the Doukhobors and brought their persecution to the attention of the international community, after they burned their weapons in peaceful protest in 1895. He aided the Doukhobors in migrating to Canada.

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates text from D.S. Mirsky's "A History of Russian Literature" (1926-27), a publication now in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from D.S. Mirsky's "A History of Russian Literature" (1926-27), a publication now in the public domain.

- Martin E. Hellman, Resist Not Evil in World Without Violence (Arun Gandhi ed.), M.K. Gandhi Institute, 1994, retrieved on 14 December 2006]

- Victor Terras ed., Handbook of Russian Literature, p. 476-480, Yale University Press, 1985 (retrieved on 14 December 2006 from this website)

- Woodcock, George. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements, Broadview Press, 2004, p. 185

Media

Template:Multi-video start Template:Multi-video item Template:Multi-video end

External links

| This article's use of external links may not follow Misplaced Pages's policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links, and converting useful links where appropriate into footnote references. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Leo Tolstoy dedicated websites

Biographies and critiques

- Illustrated Biography online at University of Virginia

- Tolstoy and Popular Literature - Several scientific papers from the University of Minnesota

- Brief bio

- Leo Tolstoy's Life - Tolstoy's personal, professional and world event timeline, and synopsis of his life from Masterpiece Theatre.

- The Last Days of Leo Tolstoy

- Aleksandra Tolstaya, "Tragedy of Tolstoy"

- Template:Ru icon The ancestors Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy

- Template:Ru icon The World of Leo Tolstoy

- Information and Critique on Leo Tolstoy

- Leo Tolstoy Chronicle by Erik Lindgren

- Tolstoy's Legacy for Mankind: A Manifesto for Nonviolence, Part 1

- Tolstoy's Legacy for Mankind: A Manifesto for Nonviolence, Part 2

- Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool an essay by George Orwell

- article written on Tolstoy's 80th birthday by Leon Trotsky

- Simon Farrow, Leo Tolstoy: Sinner, Novelist, Prophet, Proceedings of the Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution, Vol. 9, 18 January 2005

- S.F. Yegorov, Leo Tolstoy, in PROSPECTS: the quarterly review of comparative education, Vol XXIV, no 3/4, June 1994, UNESCO, p. 647-660 (about Tolstoy's writings on education)

Sources

- Works by Leo Tolstoy at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Leo Tolstoy at Internet Archive

- Works by Leo Tolstoy at University of Virginia

- Tolstoy Library

- Leo Tolstoy at Great Books Online

- Walk in the Light: And Twenty-Three Tales (Free ebook)

- Free to read on a cell phone Tolstoy works.

Leo Tolstoy in the media

- Leo Tolstoy at IMDb

- ALEXANDER II AND HIS TIMES: A Narrative History of Russia in the Age of Alexander II, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky

- Anarchists

- Christian pacifists

- Christian vegetarians

- Leo Tolstoy

- Tolstoy family

- Russian novelists

- Russian essayists

- Russian short story writers

- Russian spiritual writers

- Russian philosophers

- Russian fabulists

- Russian anarchists

- Russian pacifists

- Russian anti-war activists

- Russian vegetarians

- Aphorists

- Christian writers

- Founders of religions

- Russian adoptees

- Esperantists

- 1828 births

- 1910 deaths