This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Fovean Author (talk | contribs) at 03:02, 7 September 2007 (→Controversy). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

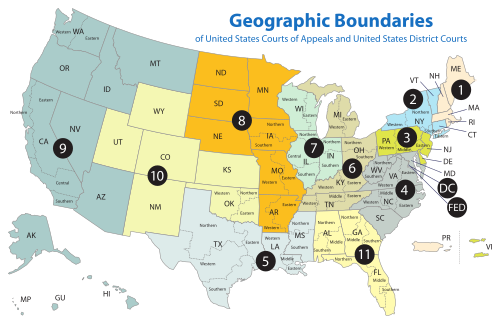

Revision as of 03:02, 7 September 2007 by Fovean Author (talk | contribs) (→Controversy)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit is a federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the district courts in the following districts:

- District of Alaska

- District of Arizona

- Central District of California

- Eastern District of California

- Northern District of California

- Southern District of California

- District of Hawaii

- District of Idaho

- District of Montana

- District of Nevada

- District of Oregon

- Eastern District of Washington

- Western District of Washington

It also has appellate jurisdiction over the following territorial courts:

Headquartered in San Francisco, the Ninth Circuit is by far the largest of the thirteen courts of appeals, with 28 active judgeships. The court's regular meeting places are Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, and Pasadena, but panels of the court occasionally travel to hear cases in other locations within its territorial jurisdiction. Although the judges travel around the circuit, the court arranges its hearings so that cases from the northern region of the circuit are heard in Seattle or Portland, cases from southern California are heard in Pasadena, and cases from northern California, Nevada, Arizona, and Hawaii are heard in San Francisco. For lawyers who must come and present their cases to the court in person, this administrative grouping of cases helps to reduce the time and cost of travel.

History and background

| Year | Jurisdiction | Total population | Pop. as % of nat'l pop. | Number of active judgeships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1891 | CA, ID, MT, NV, OR, WA | 2,087,000 | 3.3% | 2 |

| 1900 | CA, HI, ID, MT, NV, OR, WA | 2,798,000 | 3.7% | 3 |

| 1920 | AZ, CA, HI, ID, MT, NV, OR, WA | 7,415,000 | 6.7% | 3 |

| 1940 | AZ, CA, HI, ID, MT, NV, OR, WA | 11,881,000 | 9.0% | 7 |

| 1960 | AK, AZ, CA, GU, HI, ID, MT, NV, OR, WA | 22,607,000 | 12.6% | 9 |

| 1980 | AK, AZ, CA, GU, HI, ID, MT, NV, OR, WA | 37,170,000 | 16.4% | 23 |

| 2000 | AK, AZ, CA, GU, HI, ID, MT, NV, OR, WA | 54,575,000 | 19.3% | 28 |

The large size of the current court is due to the fact that both the population of the western states and the geographic jurisdiction of the Ninth Circuit have increased dramatically since Congress, in 1891, created the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The court was originally granted appellate jurisdiction over federal district courts in California, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington. As new states and territories were added to the federal judicial hierarchy in the twentieth century, many of those in the West came under control of the Ninth Circuit: the newly acquired territory of Hawaii in 1900, Arizona upon its accession to statehood in 1912, the then-territory of Alaska in 1948, Guam in 1951, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) in 1977. The adjoining chart illustrates the scope of the Ninth Circuit's jurisdiction at its inception in 1891 and at 20-year intervals since 1900.

The cultural and political jurisdiction of the Ninth Circuit is just as varied as the land within its geographical borders. In a dissenting opinion in a rights of publicity case involving Wheel of Fortune star Vanna White, Circuit Judge Alex Kozinski sardonically noted that “or better or worse, we are the Court of Appeals for the Hollywood Circuit.” Judges from more remote parts of the circuit note the contrast between legal issues confronted by populous states such as California and those confronted by rural states such as Alaska, Idaho, and Montana. Judge Andrew J. Kleinfeld, who maintains his chambers in Fairbanks, Alaska, wrote in a 1998 letter: “Much federal law is not national in scope…. It is easy to make a mistake construing these laws when unfamiliar with them, as we often are, or not interpreting them regularly, as we never do.”

Many scholars and jurists, like Judge Kleinfeld, cite regional differences between states in the circuit, as well as the practical, procedural, and substantive difficulties in administering a court of this size, as reasons why Congress should split the Ninth Circuit into two or more smaller circuit courts. Opponents of such a move claim that the court is functioning smoothly from an administrative standpoint, and that the real problem is not that the circuit is too large, but that Congress has not created enough judgeships to handle the court's workload. Moreover, many who advocate the preservation of the current Ninth Circuit see politics as a motivating factor in the split movement. They claim that by implementing a scheme that isolates California from the other states in the circuit, the effect of a split will be to dilute the power of judges who have handed down rulings that have angered social conservatives.

Controversy

Most criticism of the Ninth Circuit can be summarized by the following two claims:

- The Ninth Circuit is politically liberal and out of step with Supreme Court precedent.

- The large size of the court prevents it from maintaining a coherent body of case law.

Political liberalism

| This article possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

According to the most current count, the Ninth Circuit has the highest percentage of active judges appointed by Democratic presidents, with 59%. Until 2003, this percentage was much higher; a political stalemate over judicial nominations subsequently kept several vacancies on the court for several years.

Critics point to this preponderance of appointees of Democratic presidents as evidence that the court has a liberal bias. Such critics often point to 2002's Newdow v. U.S. Congress, in which the court declared that a public school district in Elk Grove, California could not force students to recite the Pledge of Allegiance; the pledge's inclusion of the words "under God," the court held, violated the Establishment Clause. The case was brought by Michael Newdow, an atheist who felt that the daily recitation of the Pledge in his daughter's school violated her First Amendment right to be free from government establishment of religion. In a 2-1 decision, a Ninth Circuit panel held for Newdow, stating that “he text of the official Pledge, codified in federal law, impermissibly takes a position with respect to the purely religious question of the existence and identity of God.” The majority opinion was written by Alfred T. Goodwin, who was appointed to the court by Richard M. Nixon, a Republican.

In 2004, the United States Supreme Court reversed the Ninth Circuit's decision. However, the majority opinion did not reach the substantive issue of whether the Pledge violated the Establishment Clause, instead holding that Newdow, who did not have primary custody of his daughter (the child's mother, whom Newdow never married, had custody), did not have standing to litigate the claim in federal court. Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justices Sandra Day O'Connor and Clarence Thomas disagreed with the majority's opinion of Newdow's standing, but concurred in the judgment, making this a unanimous decision reversing the Ninth Circuit. Thomas wrote that the Ninth Circuit's opinion was “a persuasive reading of (Supreme Court) precedent,” but then attacked the precedent, particularly Lee v. Weisman. Rehnquist and O'Connor disagreed with the Ninth Circuit's interpretation of the precedent.

Indeed, while the Ninth Circuit had long been instrumental in striking new legal ground, particularly in the areas of immigration law and prisoner rights, it was the Newdow decision that galvanized criticism against what conservatives saw as “judicial activism.” Reaction to the decision by prominent political leaders, especially those in the House and Senate, was passionate. President George W. Bush, through his spokesman Ari Fleischer, called the ruling “ridiculous,” while Senator Charles Grassley called it “crazy and outrageous.” Even mainstream Democrats attacked the decision, with House minority leader Richard Gephardt calling it “poorly thought out.” Criticisms of the Newdow decision were not limited to the substantive law considered by the judges who heard the case; they also attacked the legitimacy and political independence of the court itself. The result was a renewed focus on the Ninth Circuit's caseload and a targeted effort by congressional Republicans to minimize the impact of such decisions.

Another hotly contested case considered by the Ninth Circuit arose from the enactment of a California law permitting the cultivation and use of marijuana for medicinal purposes. In Raich v. Ashcroft, 352 F.3d 1222 (9th Cir. 2003), rev'd sub nom. Gonzales v. Raich, 545 U.S. 1 (2005), a cancer patient sued the federal government, seeking to prevent it from seizing her supply of medical marijuana under the federal Controlled Substances Act. The United States argued that it had the right to enforce its drug laws against Raich notwithstanding the California statute. Raich argued that since the marijuana was grown within California, had never left the state's borders, and was not part of any economic transaction, Congress had no constitutional authority to regulate her cultivation and use of marijuana. In holding for Raich, the Ninth Circuit adhered to two landmark Supreme Court cases, United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549 (1995), and United States v. Morrison, 529 U.S. 598 (2000), which had substantially restricted Congress's authority to regulate “noneconomic” activity under the guise of the Commerce Clause to the United States Constitution. In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court disagreed with this analysis, adhering instead to a 1942 case, Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U.S. 111 (1942), in which the Court held that cultivation of wheat for personal consumption could be subject to a federal production quota even though the crop never entered the stream of commerce. Interestingly, the three dissenters—voting to uphold the Ninth Circuit—were Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist and Justice Clarence Thomas, considered to be two of the most conservative members of the Court, as well as Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, considered to be a moderate. The Raich litigation illustrates that although the result of the Ninth Circuit's decision pleased political liberals opposed to tough federal drug laws, the legal analysis employed by the court was faithful to the principles of federalism and thus wholly “conservative” from a legal perspective.

On the other hand, not every Supreme Court reversal of a Ninth Circuit decision has come in a case where the appellate judges ruled in favor of a group championed by political liberals. In Kyllo v. United States, 533 U.S. 27 (2001), the Supreme Court reversed a decision of the Ninth Circuit in favor of the government. The Ninth Circuit had ruled that evidence of a marijuana-growing operation obtained without a warrant by means of a thermal imaging device could be introduced at a criminal trial because the Fourth Amendment did not recognize an expectation of privacy in radiation emanating from a private home. The Supreme Court reversed because a person's home is a place where he has always had an expectation of privacy, such that the search at issue required a warrant.

Size of the court

In addition to concerns over its legal doctrine, critics of the Ninth Circuit point out several adverse consequences of its large size. Chief among these is the Ninth Circuit's unique rules concerning the composition of an en banc court. In other circuits, en banc courts are composed of all active circuit judges, plus (depending on the rules of the particular court) any senior judges who took part in the original panel decision. By contrast, in the Ninth Circuit it is impractical for twenty-eight or more judges to take part in a single oral argument and deliberate on a decision en masse. The court thus provides for a “limited en banc” review of a randomly-selected 15 judge panel. This means that en banc reviews may not actually reflect the views of the majority of the court, and indeed may not include any of the three judges involved in the decision being reviewed in the first place. The result, according to detractors, is a high risk of intracircuit conflicts of law where different groupings of judges end up delivering contradictory opinions. This is said to cause uncertainty in the district courts and within the bar. Supporters of the existing court, however, point out that en banc review is a relatively rare occurrence and that court rules provide for full en banc review in limited circumstances. Supporters also point out that all currently proposed splits would leave at least one circuit with 21 judges, only two fewer than the 23 that the Ninth Circuit had when the limited en banc procedure was first adopted; in other words, after a split at least one of the circuits would still be utilizing limited en banc courts.

In March 2007, Justices Anthony Kennedy and Clarence Thomas testified before a House Appropriations subcommittee that the consensus among the justices of the Supreme Court of the United States was that the Ninth Circuit was too large and unwieldy and should be split.

Most overturned court in the United States

Of the 80 cases the Supreme Court decided this past term through opinions, 56 cases arose from the federal appellate courts, three from the federal district courts, and 21 from the state courts. The court reversed or vacated the judgment of the lower court in 59 of these cases. Specifically, the justices overturned 40 of the 56 judgments arising from the federal appellate courts (or 71%), two of the three judgments coming from the federal district courts (or 67%), and 17 of the 21 judgments issued by state courts (or 81%).

Notably, the 9th Circuit accounted for both 30 percent of the cases (24 of 80) and 30 percent of the reversals (18 of 59) the Supreme Court decided by full written opinions this term. In addition, the 9th Circuit was responsible for more than a third (35%, or 8 of 23) of the High Court’s unanimous reversals that were issued by published opinions. Thus, on the whole, the 9th Circuit’s rulings accounted for more reversals this past term than all the state courts across the country combined and represented nearly half of the overturned judgments (45%) of the federal appellate courts.

Ninth Circuit split proposals

The following are the most prominent of the several existing or former proposals that have been considered by congressional leaders, legislative commissions, and interest groups.

- Commission on Structural Alternatives for the Federal Courts of Appeals, Final Report, Dec. 18, 1998

- The Commission found that splitting the Ninth Circuit would be “impractical and … unnecessary.” However, it recommended that the circuit be divided into three “adjudicative divisions” each of which would hear appeals from specific regions. A fourth at-large “circuit division” would be invoked solely to resolve conflicts of law arising within a particular division. This proposal would also abolish circuit-wide en banc or limited en banc circuit panels, instead creating en banc panels from each of the three regions as necessary.

- Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals of Reorganization Act of 2003, S. 562

- This proposal would split the Ninth Circuit into two, with California and Nevada being retained by the new Ninth Circuit and the remaining Ninth Circuit jurisdictions being assigned to a new Twelfth Circuit. The bill would create ten new judgeships, with 25 being retained by the Ninth Circuit and 13 being assigned to the Twelfth Circuit. Each current Ninth Circuit judge would be assigned to a new circuit based on the location of his or her duty station. This proposal was co-sponsored seven by Republican Senators from Alaska, Montana, Idaho, Oklahoma, and Oregon. After a hearing by the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Administrative Oversight and the Courts on April 7, 2004, no vote was held.

- Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Judgeship and Reorganization Act of 2003, H.R. 2723

- This proposal would split the Ninth Circuit into two, with Arizona, California and Nevada being retained by the new Ninth Circuit and the remaining Ninth Circuit jurisdictions being assigned to a new Twelfth Circuit. The bill would create five permanent and two temporary judgeships, all to be retained by the new Ninth Circuit. The temporary judgeships would terminate upon the existence of a vacancy ten years or more after passage of the act. Each current Ninth Circuit judge would be assigned to a new circuit based on the location of his or her duty station. This proposal was co-sponsored by Republican congressmen from Washington, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. After a hearing by the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Courts, the Internet, and Intellectual Property on October 21, 2003, no vote was held. This bill was reintroduced in the 109th Congress as H.R. 212, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Judgeship and Reorganization Act of 2005. It is pending before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Courts, the Internet, and Intellectual Property.

- Ninth Circuit Judgeship and Reorganization Act of 2004, S. 878

- This proposal would create two new circuits, the Twelfth and Thirteenth. The Ninth Circuit would retain California, Hawaii, Guam, and the CNMI. The Twelfth Circuit would contain Arizona, Nevada, Idaho, and Montana. The Thirteenth Circuit would contain Alaska, Oregon, and Washington. The Act would provide that existing judges be assigned to new circuits based on the location of their duty stations, after which the number of active judgeships in the new Ninth Circuit would be increased to nineteen. This bill was reintroduced in the 109th Congress as the Ninth Circuit Judgeship and Reorganization Act of 2005, H.R. 211, co-sponsored by House Majority Leader Tom DeLay and the same Republican Congressmen who had sponsored the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Judgeship and Reorganization Act of 2003.

- The Circuit Court of Appeals Restructuring and Modernization Act of 2005, S. 1845

- This proposal would split the Ninth Circuit into two, with California, Hawaii, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands being retained by the Ninth Circuit, and the remaining Ninth Circuit jurisdictions being assigned to new Twelfth Circuit. It would create five permanent and two temporary judgeships, all retained by the new Ninth Circuit. The temporary judgeships would terminate upon the existence of a vacancy ten years or more after passage of the act. Each current Ninth Circuit judge would be assigned to a new circuit based on the location of his or her duty station. The proposal was co-sponsored by nine Republican senators from Alaska, Arizona, Montana, Nevada, Idaho, Oklahoma, and Oregon, including the same group of senators that had sponsored S. 562 in the previous Congress. It is pending before the Judiciary Subcommittee on Administrative Oversight and the Courts, and hearings have been held on it. It would seem to supersede S. 1296, which is similar in the states assigned to each new circuit and the number of judgeships in each new circuit; every sponsor of S. 1296 also sponsors S. 1845.

Current composition of the court

As of Randy Smith's confirmation on February 15, 2007, the judges on the court are:

| # | Title | Judge | Duty station | Born | Term of service | Appointed by | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active | Chief | Senior | ||||||

| 46 | Chief Judge | Mary M. Schroeder | Phoenix, AZ | 1940 | 1979–present | 2000–present | — | Carter |

| 50 | Circuit Judge | Harry Pregerson | Woodland Hills, CA | 1923 | 1979–present | — | — | Carter |

| 57 | Circuit Judge | Stephen Reinhardt | Los Angeles, CA | 1931 | 1980–present | — | — | Carter |

| 62 | Circuit Judge | Alex Kozinski | Pasadena, CA | 1950 | 1985–present | — | — | Reagan |

| 65 | Circuit Judge | Diarmuid Fionntain O'Scannlain | Portland, OR | 1937 | 1986–present | — | — | Reagan |

| 69 | Circuit Judge | Pamela Ann Rymer | Pasadena, CA | 1941 | 1989–present | — | — | G.H.W. Bush |

| 71 | Circuit Judge | Andrew Jay Kleinfeld | Fairbanks, AK | 1945 | 1991–present | — | — | G.H.W. Bush |

| 72 | Circuit Judge | Michael Daly Hawkins | Phoenix, AZ | 1945 | 1994–present | — | — | Clinton |

| 74 | Circuit Judge | Sidney Runyan Thomas | Billings, MT | 1953 | 1996–present | — | — | Clinton |

| 75 | Circuit Judge | Barry G. Silverman | Phoenix, AZ | 1951 | 1998–present | — | — | Clinton |

| 76 | Circuit Judge | Susan P. Graber | Portland, OR | 1949 | 1998–present | — | — | Clinton |

| 77 | Circuit Judge | M. Margaret McKeown | San Diego, CA | 1951 | 1998–present | — | — | Clinton |

| 78 | Circuit Judge | Kim McLane Wardlaw | Pasadena, CA | 1954 | 1998–present | — | — | Clinton |

| 79 | Circuit Judge | William A. Fletcher | San Francisco, CA | 1945 | 1998–present | — | — | Clinton |

| 80 | Circuit Judge | Raymond C. Fisher | Pasadena, CA | 1939 | 1999–present | — | — | Clinton |

| 81 | Circuit Judge | Ronald M. Gould | Seattle, WA | 1946 | 1999–present | — | — | Clinton |

| 82 | Circuit Judge | Richard A. Paez | Pasadena, CA | 1947 | 2000–present | — | — | Clinton |

| 83 | Circuit Judge | Marsha L. Berzon | San Francisco, CA | 1945 | 2000–present | — | — | Clinton |

| 84 | Circuit Judge | Richard C. Tallman | Seattle, WA | 1953 | 2000–present | — | — | Clinton |

| 85 | Circuit Judge | Johnnie B. Rawlinson | Las Vegas, NV | 1952 | 2000–present | — | — | Clinton |

| 86 | Circuit Judge | Richard R. Clifton | Honolulu, HI | 1950 | 2002–present | — | — | G.W. Bush |

| 87 | Circuit Judge | Jay Bybee | Las Vegas, NV | 1953 | 2003–present | — | — | G.W. Bush |

| 88 | Circuit Judge | Consuelo Maria Callahan | Sacramento, CA | 1950 | 2003–present | — | — | G.W. Bush |

| 89 | Circuit Judge | Carlos T. Bea | San Francisco, CA | 1934 | 2003–present | — | — | G.W. Bush |

| 90 | Circuit Judge | Milan D. Smith, Jr. | Pasadena, CA | 1942 | 2006–present | — | — | G.W. Bush |

| 91 | Circuit Judge | Sandra Segal Ikuta | Pasadena, CA | 1954 | 2006–present | — | — | G.W. Bush |

| 92 | Circuit Judge | N. Randy Smith | Pocatello, Idaho | 1949 | 2007–present | – | – | G.W. Bush |

| — | Circuit Judge | (vacant - seat 5) | (n/a) | (n/a) | (n/a) | (n/a) | (n/a) | (n/a) |

| 29 | Senior Circuit Judge | James R. Browning | San Francisco, CA | 1918 | 1961–2000 | 1976–1988 | 2000–present | Kennedy |

| 38 | Senior Circuit Judge | Alfred Theodore Goodwin | Pasadena, CA | 1923 | 1971–1991 | 1988–1991 | 1991–present | Nixon |

| 39 | Senior Circuit Judge | J. Clifford Wallace | San Diego, CA | 1928 | 1972–1996 | 1991–1996 | 1996–present | Nixon |

| 40 | Senior Circuit Judge | Joseph Tyree Sneed III | San Francisco, CA | 1920 | 1973–1987 | (none) | 1987–present | Nixon |

| 43 | Senior Circuit Judge | Procter Ralph Hug, Jr. | Reno, NV | 1931 | 1977–2002 | 1996–2000 | 2002–present | Carter |

| 45 | Senior Circuit Judge | Betty Binns Fletcher | Seattle, WA | 1923 | 1979–1998 | (none) | 1998–present | Carter |

| 47 | Senior Circuit Judge | Otto Richard Skopil, Jr. | Portland, OR | 1919 | 1979–1986 | (none) | 1986–present | Carter |

| 48 | Senior Circuit Judge | Joseph Jerome Farris | Seattle, WA | 1930 | 1979–1995 | (none) | 1995–present | Carter |

| 49 | Senior Circuit Judge | Arthur Lawrence Alarcon | Los Angeles, CA | 1925 | 1979–1992 | (none) | 1992–present | Carter |

| 51 | Senior Circuit Judge | Warren John Ferguson | Santa Ana, CA | 1920 | 1979–1986 | (none) | 1986–present | Carter |

| 53 | Senior Circuit Judge | Dorothy Wright Nelson | Pasadena, CA | 1928 | 1979–1995 | (none) | 1995–present | Carter |

| 54 | Senior Circuit Judge | William Cameron Canby, Jr. | Phoenix, AZ | 1931 | 1980–1996 | (none) | 1996–present | Carter |

| 55 | Senior Circuit Judge | Robert Boochever | Pasadena, CA | 1917 | 1980–1986 | (none) | 1986–present | Carter |

| 58 | Senior Circuit Judge | Robert R. Beezer | Seattle, WA | 1928 | 1984–1996 | (none) | 1996–present | Reagan |

| 59 | Senior Circuit Judge | Cynthia Holcomb Hall | Pasadena, CA | 1929 | 1984–1997 | (none) | 1997–present | Reagan |

| 61 | Senior Circuit Judge | Melvin T. Brunetti | Reno, NV | 1933 | 1985–1999 | (none) | 1999–present | Reagan |

| 63 | Senior Circuit Judge | John T. Noonan, Jr. | San Francisco, CA | 1926 | 1985–1996 | (none) | 1996–present | Reagan |

| 64 | Senior Circuit Judge | David R. Thompson | San Diego, CA | 1930 | 1985–1998 | (none) | 1998–present | Reagan |

| 66 | Senior Circuit Judge | Edward Leavy | Portland, OR | 1929 | 1987–1997 | (none) | 1997–present | Reagan |

| 67 | Senior Circuit Judge | Stephen S. Trott | Boise, ID | 1939 | 1988–2004 | (none) | 2005–present | Reagan |

| 68 | Senior Circuit Judge | Ferdinand Francis Fernandez | Pasadena, CA | 1937 | 1989–2002 | (none) | 2002–present | G.H.W. Bush |

| 70 | Senior Circuit Judge | Thomas G. Nelson | Boise, ID | 1936 | 1990–2003 | (none) | 2003–present | G.H.W. Bush |

| 73 | Senior Circuit Judge | Atsushi Wallace Tashima | Pasadena, CA | 1934 | 1996–2004 | (none) | 2004–present | Clinton |

Pending nominations

- There are no pending nominations at this time.

List of former judges

| # | Judge | State | Born–died | Active service | Chief Judge | Senior status | Appointed by | Reason for termination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lorenzo Sawyer | CA | 1820–1891 | 1891–1891 | (none) | (none) | death | |

| 2 | Joseph McKenna | CA | 1843–1926 | 1892–1897 | (none) | (none) | B. Harrison | resignation |

| 3 | William Ball Gilbert | OR | 1847–1931 | 1892–1931 | (none) | (none) | B. Harrison | death |

| 4 | Erskine Mayo Ross | CA | 1845–1928 | 1895–1925 | (none) | 1925–1928 | Cleveland | death |

| 5 | William W. Morrow | CA | 1843–1929 | 1897–1923 | (none) | (none) | McKinley | resignation |

| — | William Henry Hunt | MT | 1857–1949 | 1911–1928 | (none) | 1928–1928 | resignation | |

| 6 | Frank H. Rudkin | WA | 1864–1931 | 1923–1931 | (none) | (none) | Harding | death |

| 7 | Wallace McCamant | OR | 1867–1944 | 1925–1926 | (none) | (none) | Coolidge | recess appointment not confirmed by the Senate |

| 8 | Frank Sigel Dietrich | ID | 1863–1930 | 1927–1930 | (none) | (none) | Coolidge | death |

| 9 | Curtis D. Wilbur | CA | 1867–1954 | 1929–1945 | (none) | 1945–1954 | Hoover | death |

| 10 | William Henry Sawtelle | AZ | 1868–1934 | 1931–1934 | (none) | (none) | Hoover | death |

| 11 | Francis Arthur Garrecht | WA | 1870–1948 | 1933–1948 | (none) | (none) | F. Roosevelt | death |

| 12 | William Denman | CA | 1872–1959 | 1935–1957 | 1948–1957 | 1957–1959 | F. Roosevelt | death |

| 13 | Clifton Mathews | AZ | 1880–1962 | 1935–1953 | (none) | 1953–1962 | F. Roosevelt | death |

| 14 | Bert Emory Haney | OR | 1879–1943 | 1935–1943 | (none) | (none) | F. Roosevelt | death |

| 15 | Albert Lee Stephens, Sr. | CA | 1874–1965 | 1937–1961 | 1957–1959 | 1961–1965 | F. Roosevelt | death |

| 16 | William Healy | ID | 1881–1962 | 1937–1958 | (none) | 1958–1962 | F. Roosevelt | death |

| 17 | Homer Bone | WA | 1883–1970 | 1944–1956 | (none) | 1956–1970 | F. Roosevelt | death |

| 18 | William Edwin Orr | NV | 1881–1965 | 1945–1956 | (none) | 1956–1965 | Truman | death |

| 19 | Walter Lyndon Pope | MT | 1889–1969 | 1949–1961 | 1959–1959 | 1961–1969 | Truman | death |

| 20 | Dal Millington Lemmon | CA | 1887–1958 | 1954–1958 | (none) | (none) | Eisenhower | death |

| 21 | Richard Harvey Chambers | AZ | 1906–1994 | 1954–1976 | 1959–1976 | 1976–1994 | Eisenhower | death |

| 22 | James Alger Fee | OR | 1888–1959 | 1954–1959 | (none) | (none) | Eisenhower | death |

| 23 | Stanley Nelson Barnes | CA | 1900–1990 | 1956–1970 | (none) | 1970–1990 | Eisenhower | death |

| 24 | Frederick George Hamley | WA | 1903–1975 | 1956–1971 | (none) | 1971–1975 | Eisenhower | death |

| 25 | Oliver Deveta Hamlin, Jr. | CA | 1892–1973 | 1958–1963 | (none) | 1963–1973 | Eisenhower | death |

| 26 | Gilbert H. Jertberg | CA | 1897–1973 | 1958–1967 | (none) | 1967–1973 | Eisenhower | death |

| 27 | Charles Merton Merrill | NV | 1907–1996 | 1959–1974 | (none) | 1974–1996 | Eisenhower | death |

| 28 | Montgomery Oliver Koelsch | ID | 1912–1992 | 1959–1976 | (none) | 1976–1992 | Eisenhower | death |

| 30 | Benjamin Cushing Duniway | CA | 1907–1986 | 1961–1976 | (none) | 1976–1986 | Kennedy | death |

| 31 | Walter Raleigh Ely, Jr. | CA | 1913–1979 | 1964–1979 | (none) | 1979–1984 | L. Johnson | death |

| 32 | James Marshall Carter | CA | 1904–1979 | 1967–1971 | (none) | 1971–1979 | L. Johnson | death |

| 33 | Shirley Hufstedler | CA | 1925– | 1968–1979 | (none) | (none) | L. Johnson | Appointed U.S. Secretary of Education |

| 34 | Eugene Allen Wright | WA | 1913–2002 | 1969–1983 | (none) | 1983–2002 | Nixon | death |

| 35 | John Francis Kilkenny | OR | 1901–1995 | 1969–1971 | (none) | 1971–1995 | Nixon | death |

| 36 | Ozell Miller Trask | AZ | 1909–1984 | 1971–1984 | (none) | (none) | Nixon | death |

| 37 | Herbert Choy | HI | 1916–2004 | 1971–1984 | (none) | 1984–2004 | Nixon | death |

| 41 | Anthony Kennedy | CA | 1936– | 1975–1988 | (none) | (none) | Ford | elevation to Supreme Court |

| 42 | J. Blaine Anderson | ID | 1922–1988 | 1976–1988 | (none) | (none) | Ford | death |

| 44 | Thomas Tang | AZ | 1922–1995 | 1977–1993 | (none) | 1993–1995 | Carter | death |

| 52 | Cecil F. Poole | CA | 1914–1997 | 1979–1996 | (none) | 1996–1997 | Carter | death |

| 56 | William Albert Norris | CA | 1927– | 1980–1994 | (none) | 1994–1997 | Carter | retirement |

| 60 | Charles Edward Wiggins | CA | 1927–2000 | 1984–1996 | (none) | 1996–2000 | Reagan | death |

Chief judges

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Chief judges have administrative responsibilities with respect to their circuits, and preside over any panel on which they serve, unless the circuit justice (the Supreme Court justice responsible for the circuit) is also on the panel. Unlike the Supreme Court, where one justice is specifically nominated to be chief, the office of chief judge rotates among the circuit judges.

To be chief, a judge must have been in active service on the court for at least one year, be under the age of 65, and have not previously served as chief judge. A vacancy is filled by the judge highest in seniority among the group of qualified judges, with seniority determined first by commission date, then by age. The chief judge serves for a term of seven years, or until age 70, whichever occurs first. If no judge qualifies to be chief, the youngest judge over the age of 65 who has served on the court for at least one year shall act as chief until another judge qualifies. If no judge has served on the court for more than a year, the most senior judge shall act as chief. Judges can forfeit or resign their chief judgeship or acting chief judgeship while retaining their active status as a circuit judge.

When the office was created in 1948, the chief judge was the longest-serving judge who had not elected to retire, on what has since 1958 been known as senior status, or declined to serve as chief judge. After August 6, 1959, judges could not become or remain chief after turning 70 years old. The current rules have been in operation since October 1, 1982.

Succession of seats

The court has 28 seats for active judges, numbered in the order in which they were initially filled. Judges who assume senior status enter a kind of retirement in which they remain on the bench but vacate their seats, thus allowing the U.S. President to appoint new judges to fill their seats.

See also

Notes

- Kleinfeld, Andrew J. (1998-05-22). Memo to the Commission on Structural Alternatives for the Federal Courts of Appeals. URL accessed on June 21, 2005.

- O'Scannlain, Diarmuid (2005). "Ten Reasons Why the Ninth Circuit Should Be Split" (PDF). Engage. 6 (2): 58–64. Retrieved 2006-05-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Statement of Circuit Judge Alex Kozinski to the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Courts" (PDF). The Federal Bar Association. 2003-10-21. Retrieved 2006-06-06.

- Schroeder, Mary M. (2006). "A Court United: A Statement of a Number of Ninth Circuit Judges" (PDF). Engage. 7 (1): 63–66. Retrieved 2006-06-06.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - C-SPAN America and the Courts, (03/17/2007).

- Sawyer was appointed as a circuit judge for the Ninth Circuit in 1869 by Ulysses S. Grant. The Judiciary Act of 1891 reassigned his seat to what is now the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

- Hunt did not have a permanent seat on this court. Instead, he was appointed to the ill-fated United States Commerce Court in 1911 by William Howard Taft. Aside from their duties on the Commerce Court, the judges of the Commerce Court also acted as at-large appellate judges, able to be assigned by the Chief Justice of the United States to whichever circuit most needed help. Hunt was assigned to the Ninth Circuit upon his commission.

- Recess appointment.

- 28 U.S.C. § 45

- 62 Stat. 871, 72 Stat. 497, 96 Stat. 51

External links

- United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

- This website includes links to the court's published and unpublished opinions, court-specific rules of appellate procedure, and general operating procedures.

- Recent opinions from FindLaw

- Federal Judicial Center

- “The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals: To Split Or Not To Split?” (article in WSJ)

- Disposition of Supreme Court decisions on certiorari or appeal from state and territory supreme courts, and from federal courts of appeals, 1950-2006

Navigation

| United States federal courts | |

|---|---|

| |

| Courts of appeals | |

| District courts |

|

| Specialty courts | |

| Territorial courts | |

| Extinct courts | |

| Note | American Samoa does not have a district court or federal territorial court; federal matters there go to the District of Columbia, Hawaii, or its own Supreme Court. |