This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Evilphoenix (talk | contribs) at 02:00, 31 May 2005 (copyediting introduction). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 02:00, 31 May 2005 by Evilphoenix (talk | contribs) (copyediting introduction)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

Korean Buddhism is distinguished from other forms of Buddhism by its attempt to resolve what it sees as inconsistencies in Chinese Mahayana Buddhism. Early Korean monks believed that the traditions they received from China were internally inconsistent. To address this, they developed a new holistic approach to Buddhism. This approach is characteristic of virtually all major Korean thinkers, and has resulted in a distinct variation of Buddhism, which Weonhyo (617–686) called the Tongbulgyo ("interpenetrated Buddhism"). Korean Buddhist thinkers refined their Chinese predecessors' ideas into a distinct form. Korean Buddhism then went on to have strong effects on Buddhism in Japan and the West. Several Buddhist lineages in Japan trace their roots through Korean teachers.

As it now stands, Korean Buddhism consists mostly of the Seon lineage. Seon has a strong relationship with other Mahayana traditions that bear the imprint of Chinese Ch'an teachings, as well as the closely related Japanese Zen. Other sects, such as the Taego, and the newly formed Won, have also attracted sizable followings.

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

| History |

| Buddhist texts |

| Practices |

| Nirvāṇa |

| Traditions |

| Buddhism by country |

Historical overview of the development of Korean Buddhism

Buddhism was originally introduced to Korea from China between 200 and 300 BCE, or about 800 years after the death of the historical Buddha. Though it initially enjoyed wide acceptance, even being supported as the state ideology during the Goryeo period, Buddhism in Korea suffered extreme repression during the Joseon dynasty, which lasted for several hundred years. During this period, Neo-Confucian ideology overcame the prior dominance of Buddhism.

Only after Buddhist monks helped repel a Japanese invasion at the end of the 16th century (see Seven-Year War) did the persecution of Buddhism and Buddhist practitioners stop. Buddhism in Korea remained subdued until the end of the Joseon period, when its position was strengthened somewhat by the Japanese occupation, which lasted from 1910 to 1945. After World War II, the Seon school of Korean Buddhism once again gained acceptance.

As Christianity has become increasingly influential in Korea, it is estimated that the declining Buddhist community in South Korea now accounts for about 40% of the country's population. In officially atheist North Korea, Buddhists make up 2% of the population.

Buddhism in the Three Kingdoms

The exact date of Buddhism's introduction to Korea is unknown, but is thought to be between the 3rd and 4th century CE. At that time, the Korean peninsula was politically subdivided into three kingdoms:

In 372 the Chinese monk Sundo (順道, or Shundao in Chinese) was sent by the Qin ruler Fujian (符堅) to the court of the king Sosurim (小獸林) of Goguryeo. In 384, the Serindian monk Maranant'a arrived in Baekje. Buddhism did not enter the kingdom of Silla until the 5th century.

Many Korean Buddhist monks traveled to China in order to study the buddhadharma in the late Three Kingdoms Period, especially in the late 6th century. The monk Banya (波若; 562-613?) is said to have studied under the Tiantai master Zhiyi, and Gyeomik of Baekje (謙益;) and travelled to India to learn Sanskrit and study Vinaya. Monks of the period brought back numerous scriptures from abroad and conducted missionary activity throughout Korea and Japan. The date of the first mission to Japan is unclear, but it is reported that a second detachment of scholars was sent to Japan upon invitation by the Japanese rulers in 577. The strong Korean influence on the development of Buddhism in Japan continued through the Unified Silla period; only in the 8th or 9th century did independent study by Japanese monks begin in significant numbers.

Several schools of thought developed in Korea during these early times:

- the Samnon (三論宗, or Sanlun in Chinese) school focused on the Indian Mādhyamika (Middle Path) doctrine,

- the Gyeyul (戒律宗, or Vinaya in Sanskrit) school was mainly concerned with the study and implementation of moral discipline (śīla), and

- the Yeolban (涅槃宗, or Nirvāna in Sanskrit) school, which was based in the themes of the Mahāparinirvāna-sūtra

Toward the end of the Three Kingdoms Period, the Weonyung (圓融宗, or Yuanrong in Chinese) school was formed. It would lead the actualization of the metaphysics of interpenetration as found in the Huayan jing (華嚴經) and soon was considered the premier school, especially among the educated aristocracy. This school was later known as Hwaeom (華嚴宗, or Huayan in Chinese) and was the longest lasting of these "imported" schools. It had strong ties with the Beopseong (法性宗), the indigenous Korean school of thought.

The monk Jajang (慈藏) is credited with having been a major force in the adoption of Buddhism as a national religion. Jajang is also known for his participation in the founding of the Korean sangha, a type of monastic community.

Buddhism in the Unified Silla period (668-918)

In 668, the kingdom of Silla succeeded in unifying the whole Korean peninsula, giving rise to a period of political stability that lasted for about one hundred years. This led to a high point in the scholarly studies of Buddhism in Korea. In general, the most popular areas of study were Weonyung, Yusik (Ch. 唯識; Weishi; "consciousness-only"; the East Asian form of Yogācāra), Jeongto (Pure Land), and the indigenous Korean Beopseong ("dharma-nature school"). The monk Weonhyo taught the "Pure Land"-practice of yeombul, which would become very popular amongst both scholars and laypeople, and has had a lasting influence on Buddhist thought in Korea. His work, which attempts a synthesis of the seemingly divergent strands of Indian and Chinese Buddhist doctrine, makes use of the essence-function (體用, or che-yong) framework, which was popular in native East Asian philosophical schools. His work was instrumental in the development of the dominant school of Korean Buddhist thought, known variously as Beopseong, Haedong (海東, "Korean") and later as Jungdo (中道, "Middle way")

Weonhyo's friend Uisang (義湘) went to Changan, where he studied under Huayan patriarchs Zhiyan (智儼; 600-668) and Fazang (法藏; 643-712). When he returned after twenty years, his work contributed to Hwaeom and became the predominant doctrinal influence on Korean Buddhism, together with Weonhyo's tong bulgyo thought. Hwaeom principles were deeply assimilated into the Korean meditational school, the Seon school, where they made a profound effect on its basic attitudes.

Influences from Silla Buddhism in general, and from these two philosophers in particular, even crept "backwards" into Chinese Buddhism. Weonhyo's commentaries were very important in shaping the thought of the preeminent Chinese Buddhist philosopher Fazang, and Weonchuk's commentary on the Saṃdhinirmocana-sūtra-sūtra had a strong influence in Tibetan Buddhism.

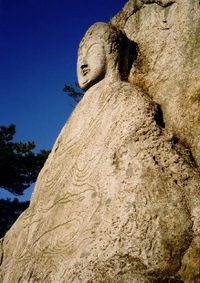

As was the case in Tang China, as well as the Nara and early Heian period in Japan, which are roughly contemporary to the Silla period, the intellectual developments of Silla Buddhism also brought with them significant cultural achievements in many areas, including painting, literature, sculpture, and architecture. During this period, many large and beautiful temples were built. Two crowning achievements were the temple Bulguksa and the cave-retreat of Seokguram (石窟庵). Bulguksa was especially famous for its jeweled pagodas, while Seokguram was known for the beauty of its stone sculpture.

A new epoch in Korean Buddhism began during the latter Silla period with the birth of schools of Seon in Korea. In China, the movement toward a meditation-based view of practice, which came to be known as chan, had begun during the sixth and seventh centuries, and it was not long before the influence of the new meditational school reached Korea, where it was known as Seon. Meaning "meditation," the term is more widely known in the West in its Japanese variant zen. Tension developed between the new meditational schools and the previously existing academically oriented schools, which were described by the term gyo, meaning "learning" or "study."

Beomnang (法朗; fl. 632-646), said to be a student of the Chinese master Daoxin (道信; 580-651), is generally credited with the initial transmission of Seon into Korea. Seon was popularized by Sinhaeng (神行; 704-779) in the latter part of the eighth century and by Doui (道義; d. 825) at the beginning of the ninth century. From then on, many Koreans studied Chan in China, and upon their return established their own schools at various mountain monasteries with their leading disciples. Initially, the number of these schools was fixed at nine, and Korean Seon was termed the "nine mountains" (九山 or gusan) school at the time. Eight of these were of the lineage of Mazu Daoyi (馬祖道一; 709-788), as they were established through connection with either him or one of his eminent disciples. The one exception was the Sumi-san school founded by Ieom (利嚴; 869-936), which had developed from the Caotong (曹洞) lineage.

Buddhism as state religion in the Goryeo period (918-1392)

Initially, the new Seon schools were regarded by the established doctrinal schools as radical and dangerous upstarts. Thus, the early founders of the various "nine mountain" monasteries met with considerable resistance, repressed by the long influence in court of the Gyo schools. The struggles which ensued continued for most of the Goryeo period, but gradually the Seon argument for the possession of the true transmission of enlightenment would gain the upper hand. The position that was generally adopted in the later Seon schools, due in large part to the efforts of Jinul, did not claim clear superiority of Seon meditational methods, but rather declared the intrinsic unity and similarities of the Seon and Gyo viewpoints. Although all these schools are mentioned in historical records, toward the end of the dynasty, Seon became dominant in its effect on the government and society, and the production of noteworthy scholars and adepts. During the Goryeo period, Seon thoroughly became a "religion of the state," receiving extensive support and privileges through connections with the ruling family and powerful members of the court.

Although most of the scholastic schools waned in activity and influence during this period of the growth of Seon, the Hwaeom school continued to be a lively source of scholarship well into the Goryeo, much of it continuing the legacy of Uisang and Weonhyo. In particular the work of Gyunyeo (均如; 923-973) prepared for the reconciliation of Hwaeom and Seon, with Hwaeom's accommodating attitude toward the latter. Gyunyeo's works are an important source for modern scholarship in identifying the distinctive nature of Korean Hwaeom.

Another important advocate of Seon/Gyo unity was Uicheon. Like most other early Goryeo monks, he began his studies in Buddhism with Hwaeom. He later traveled to China, and upon his return, actively promulgated the Cheontae (天台宗, or Tiantai in Chinese) teaching, which became recognized as another Seon school. This period thus came to be described as "five doctrinal and two meditational schools" (ogyo yangjong). Uicheon himself, however, alienated too many Seon adherents, and he died at a relatively young age without seeing a Seon-Gyo unity accomplished.

The most important figure of Seon in the Goryeo was Jinul (知訥; 1158-1210). In his time, the sangha was in a crisis of external appearance and internal issues of doctrine. Buddhism had gradually become infected by secular tendencies and involvements, such as fortune-telling and the offering of prayers and rituals for success in secular endeavors. This kind of corruption resulted in the profusion of increasingly larger numbers of monks and nuns with questionable motivations. Therefore, the correction, revival, and improvement of the quality of Buddhism were prominent issues for Buddhist leaders of the period.

Jinul sought to establish a new movement within Korean Seon, which he called the "samādhi and prajñā society", whose goal was to establish a new community of disciplined, pure-minded practitioners deep in the mountains. He eventually accomplished this mission with the founding of the Seonggwangsa monastery at Mt. Jogye (曹溪山). Jinul's works are characterized by a thorough analysis and reformulation of the methodologies of Seon study and practice. One major issue that had long fermented in Chinese Chan, and which received special focus from Jinul, was the relationship between "gradual" and "sudden" methods in practice and enlightenment. Drawing upon various Chinese treatments of this topic, most importantly those by Zongmi (780-841) and Dahui (大慧; 1089-1163), Jinul created a "sudden enlightenment followed by gradual practice" dictum, which he outlined in a few relatively concise and accessible texts. From Dahui, Jinul also incorporated the gwanhwa (觀話) method into his practice. This form of meditation is the main method taught in Korean Seon today. Jinul's philosophical resolution of the Seon-Gyo conflict brought a deep and lasting effect on Korean Buddhism.

The general trend of Buddhism in the latter half of the Goryeo was a decline due to corruption, and the rise of strong anti-Buddhist political and philosophical sentiment. However, this period of relative decadence would nevertheless produce some of Korea's most renowned Seon masters. Three important monks of this period who figured prominently in charting the future course of Korean Seon were contemporaries and friends: Gyeonghan Baeg'un (景閑白雲; 1298-1374), Taego Bou (太古普愚; 1301-1382) and Naong Hyegeun (懶翁慧勤; 1320-1376). All three went to Yuan China to learn the Linji (臨濟 or Imje in Korean) gwanhwa teaching that had been popularized by Jinul. All three returned, and established the sharp, confrontational methods of the Imje school in their own teaching. Each of the three was also said to have had hundreds of disciples, such that this new infusion into Korean Seon brought about considerable effect. Despite the Imje influence, which was generally considered to be anti-scholarly in nature, Gyeonghan and Naong, under the influence of Jinul and the traditional tong bulgyo tendency, showed an unusual interest in scriptural study, as well as a strong understanding of Confucianism and Taoism, due to the increasing influence of Chinese philosophy as the foundation of official education. From this time, a marked tendency for Korean Buddhist monks to be "three teachings" exponents appeared.

A significant historical event of the Goryeo period is the production of the first woodblock edition of the Tripitaka, called the Tripitaka Koreana. Two editions were made, the first one completed from 1210 to 1231, and the second one from 1214 to 1259. The first edition was destroyed in a fire, during an attack by Mongol invaders in 1232, but the second edition is still in existence at Haeinsa in Gyeongsang province. This edition of the Tripitaka was of high quality, and served as the standard version of the Tripitaka in East Asia for almost 700 years.

Suppression under the Joseon dynasty (1392-1910)

The Buddhist establishment at the end of the Goryeo period had become ridden with excesses. There were too many monks and nuns, a large percentage of whom were only in the sangha as a means of escaping taxation and/or government service. There were also far too many temples being supported, and too many elaborate rituals being carried out.The support of Buddhism had become a serious drain on the national economy. The government itself was suffering from rampant corruption, while also struggling with wars on its northern and eastern borders. Moreover, a new and rapidly growing Neo-Confucian ideological movement of stridently anti-Buddhist inclination gained political power.

In 1388, an influential general named Yi Seonggye (1380-1400) carried out a coup d'etat, and established himself as the first ruler of the Joseon dynasty under the reign title of Taejo in 1392 with the support of this Neo-Confucian movement. Subsequently, Buddhism was gradually suppressed for the next 500 years. The number of temples was reduced, restrictions on membership in the sangha were installed, and Buddhist monks and nuns were literally chased into the mountains, forbidden to mix with society. Joseon Buddhism, which had started off under the so-called "five doctrinal and two meditational" schools system of the Goryeo, was first condensed to two schools:Seon and Gyo. Eventually, these were further reduced to the single school of Seon.

Despite this strong suppression from the government, and vehement ideological opposition from Korean Neo-Confucianism, Seon Buddhism continued to thrive intellectually. An outstanding thinker was Giwha (己和; (Hamheo Deuktong 涵虚得通) 1376-1433), who had first studied at a Confucian academy, but then changed his focus to Buddhism, where he was initiated to the gwanhwa tradition by Muhak Jacho (無學自超; 1327-1405). He wrote many scholarly commentaries, as well as essays and a large body of poetry. Being well-versed in Confucian and Daoist philosophies, Giwha also wrote an important treatise in defense of Buddhism, from the standpoint of the intrinsic unity of the three teachings, entitled the Hyeon jeong non. In the tradition of earlier philosophers, he applied che-yong ("essence-function") and Hwaeom (sa-sa mu-ae, "mutual interpenetration of phenomena").

Common in the works of Joseon scholar-monks are writings on Hwaeom-related texts, as well as the Awakening of Faith, Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment, Śūrangama-sūtra, Diamond Sutra and the Heart Sutra. The Jogye order instituted a set curriculum of scriptural study, including the above-mentioned works, along with other shorter selections from eminent Korean monks, such as Jinul.

During the Joseon period, the number of Buddhist monasteries dropped from several hundred to a mere thirty-six. Limits were placed on the number of clergy, land area, and ages for entering the sangha. When the final restrictions were in place, monks and nuns were prohibited from entering the cities. Buddhist funerals, and even begging, were outlawed. However, some rulers occasionally appeared who looked favorably upon Buddhism and did away with some of the more suppressive regulations. The most noteworthy of these was the queen dowager Munjeong (文定王后), who, as a devout Buddhist, took control of the government in the stead of her young son Myeongjong (明宗 r. 1545-67), and immediately repealed many anti-Buddhist measures. The queen had deep respect for the brilliant monk Bou (普雨; 1515-1565), and installed him as the head of the Seon school.

One of the most important reasons for the restoration of Buddhism to a position of minimal acceptance was the role of Buddhist monks in repelling the Japanese invasion of general Toyotomi Hideyoshi, which occurred between 1592 and 1598. At that time, the government was weak from internal squabbles, and was not initially able to muster strong resistance to the incursion. The plight of the country encouraged some leaders of the sangha to organize monks into guerilla units, which enjoyed some instrumental successes. The "righteous monk" (義士; uisa) movement spread during this eight-year war, finally including several thousand monks, led by the aging Seosan Hyujeong (西山休靜; 1520-1604), a first-rate Seon master and the author of a number of important religious texts. The presence of the monks' army was a critical factor in the eventual expulsion of the Japanese invaders.

Seosan is also known for continuing efforts toward the unification of Buddhist doctrinal study and practice. His efforts were strongly influenced by Weonhyo, Jinul, and Giwha. He is considered the central figure in the revival of Joseon Buddhism, and most major streams of modern Korean Seon trace their lineages back to him through one of his four main disciples: Yujeong (1544-1610); Eongi (1581-1644), Taeneung (1562-1649) and Ilseon (1533-1608), all four of whom were lieutenants to Seosan during the war with Japan.

The biographies of Seosan and his four major disciples are similar in many respects, and these similarities are emblematic of the typical lifestyle of Seon monks of the late Goryeo and Joseon periods. Most of them began by engaging in Confucian and Daoist studies. Turning to Seon, they pursued a markedly itinerant lifestyle, wandering through the mountain monasteries. At this stage, they were initiated to the central component of Seon practice, the gong'an, or gwanhwa meditation. This gwanhwa meditation, unlike some Japanese Zen traditions, did not consist of contemplation on a lengthy, graduated series of deeper kōans. By contrast, the typical Korean approach was that "all gong'an are contained in one" and therefore it was, and still is, quite common for the practitioner to remain with one hwadu during his whole meditational career, most often Zhaozhou's "mu." Buddhism during the three centuries, from the time of Seosan down to the next Japanese incursion into Korea in the late nineteenth century, remained fairly consistent with the above-described model. A number of eminent teachers appeared during the centuries after Seosan, but the Buddhism of the late Joseon, while keeping most of the common earlier characteristics, was especially marked by a revival of Hwaeom studies, and occasionally by new interpretations of methodology in Seon study. There was also a revival, during the final two centuries, of the Pure Land (Amitābha) faith. Although the government maintained fairly tight control of the sangha, there was never again the extreme suppression of the early Joseon.

Buddhism during the Japanese occupation (1910-1945)

The Japanese occupation from 1910 to 1945 brought great suffering on the Korean people as a whole, and to the Korean sangha in particular, as it had to comply with an extensive set of Japanese regulations. However, there were some aspects of the occupation which were beneficial to Korean Buddhists. The fact that Japanese Buddhists demanded the right to proselytize in the cities brought about a lifting of the five-hundred year ban on monks and nuns entering cities. However, the formation of new Buddhist sects, such as Won Buddhism, and the presence of Christian missionaries during this period led to further turbulence in traditional Korean Buddhism. The Japanese Buddhist custom of allowing Buddhist priests to marry contradicted the lifestyle of Korean Buddhist monks and nuns, who traditionally lived in celibacy. The Japanese occupational authorities encouraged this practice, appointed their own heads of temples, and had many works of art shipped to Japan. Negotiations for the repatriation of Korean Buddhist artworks are still ongoing.

Turbulence and Decline (1945-present)

| The neutrality of this section is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Korean Buddhism" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Forces led by General Douglas MacArthur and Syngman Rhee sought a new political template in the Republic of Korea, which resulted in sweeping changes in South Korea. The new order was more western, especially more American, with an assumption of the superiority of Christianity and western valuesbover traditional Korean religions and values. With little concern for the preservation of traditional Shamanist and Buddhist heritage, aggressive and fundamentalist Christian missionary movements, supported by Syngman Rhee, advanced, while Nationalist Chinese forces collapsed, and the extensive Christian missions in China fell. European Roman Catholic missionaries sought to build influence in Korea in order to counter the threats of atheistic Communism, Korean Buddhism, and Shamanism, which they viewed as "pagan and occult religions".

There was a belief among some that if a Judeo-Christian society were cultivated within Korea, such a society would be more resistant to Communism. There was also an American-led belief that only an American satellite democracy in Korea could cope with the partition of the country and the conflict of competing superpowers that lead to the Korean War. This opinion was contrary to that of Korean traditionalists.

To further hinder the influence of Buddhism, Syngman Rhee campaigned in 1954 against the so-called "Japanized Buddhists". Western education and scholarships, and the empowerment of women and the poor, led galvanized Koreans to defragmantize the Buddhist powers. A deep rift opened between married and celibate monks. The differences were so great that fistfights over the control of temples were frequent. Monks, mostly belonging to the Jogye order, threatened to kill themselves. Many of them were against the Japanized Buddhists. As the Buddhist riots continued, the influence of Buddhism weakened further, allowing yet more Christian expansion. Buddhism continued to lose followers to Christian missionaries, who were able to capitalize on these weaknesses with offers of rice, and give hope for the future.

The former dictator, Park Chung Hee, attempted to settle the dispute by building a unified pan-national Buddhist organization, but failed. However, he supported celibate Buddhists, and his policies were reciprocated with full support.

Further turblence in the 1980's was led by president Chun Doo-hwan, who called the Buddhist temples "dens of corruption and brutality." Troops were sent to raid the country's three thousand temples, and hundreds of monks were arrested and tortured. Subsequent South Korean presidents, who have belonged to Christian denominations, are rumoured to have harassed the Korean Buddhist community as well.

The 1990's saw a number of mainstream Buddhist leaders accused of corruption and embezzlement. Christian denominations, especially Catholic and fundamentalist Protestant, exploited the moral authority vacuum to step up proselytization efforts. Religious demonstrations turned violent, with statues of Buddha and Dangun, the mythical founder of Korea, being burned. Religious leaders also attempted to rededicate Buddhist temples as Christian churches. It is estimated that attacks by radical Christians occur a few times in each year.

In 1996, five incidents of arson took place on Venerable Seung Sahn's Seoul International Zen Center at Hwangyesa. Two nearby buildings belonging to the Ponwan Chongsa Temple were totally destroyed by flames, including the Main Dharma Hall and a Hall of Arahants that housed a total of 516 hand-carved and hand-painted wooden statues. The Samsong Am Mountain Hermitage was also attacked, and the wooden bronze bell and its drum tower destroyed.

Although there are large Buddhist organizations in Korea today, Buddhist missionary forces are not large enough to challenge their Christian counterparts, owing to the fact that modern Buddhism does not typically engage in heavy proselytization. This imbalance has led to a fairly steady decline in both the number of adherents and the social influence of the Buddhist religion in South Korea.

Looking Ahead

The Seon school, which is led by the dominant Jogye order, practices disciplined traditional Seon practice at a number of major mountain monasteries in Korea, often under the direction of highly regarded masters.

Modern Seon practice is not far removed in content from the original practice of Jinul, who introduced the integrated combination of the practice of Gwanhwa meditation with the study of selected Buddhist texts. The Korean sangha life is markedly itinerant: while each monk has a "home" monastery, he will regularly travel throughout the mountains, staying as long as he wishes, studying and teaching in the style of whatever monastery is housing him. The Korean monastic training system has seen a steadily increasing influx of Western practitioner-aspirants in the second half of the twentieth century. However, there are relatively few Koreans who have converted to Buddhism from Christianity.

Especially in Seoul, where Buddhism faces a growing pressure from Christianity, tension and suspicion between the Buddhist community, and Christians and the South Korean government, can be expected to increase. Especially in regard to weddings, Christian customs have largely replaced their Buddhist counterparts. According to experts , Korean Buddhism may become extinct by the end of the 21st century.

See also

- Korean Buddhist temples

- List of Korea-related topics

- List of Korean Buddhists

- Christianity in Korea

- Manhae

External links

- Torn by identity - Christianity against Buddhism? Also shows a long list of events how Buddhists are discriminated in Korea.

- Buddhist broadcasting Korea

- Bibliography of Korean Buddhism

- Korean Buddhism: A Short Overview

- Buddhism in Korea

- Seon - The Buddhism of Korea with images of the Tripitaka.

- Monastic Buddhism in Korea

- What is Korean Buddhism? Extensive coverage of the history.

- History of Korean Buddhism from the web site of the Jogye order.

- An Overview of Korean Buddhism, a set of articles covering the history, monks' biographies, arts, and so on.

- An article from the Seoul Times

- Chronology of Buddhism and Christianity in Korea

- Links to Korean Buddhist websites

- Korean Buddhist clashes (news archive)

- Pressure of Buddhism from Christianity in Korea

- Profile:History of the growing fundamental Christian bodies in the world

- Seon--The Buddhism of Korea

- Counter-pressure between Christianity and Buddhism

- Persecution of Buddhists

- Korean ambassadors greets Buddhist protests

- The Dead and the Dying in Korea

- Korean religion - Colonial Period

- the teaching of Ven. Seongcheol Seongcheol(1912-1993), one of the most representative Korean Seon masters in modern times.

- Buddhism under Siege 1982-1996