This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Vsmith (talk | contribs) at 17:56, 8 October 2007 (Reverted edits by 72.83.170.2 (talk) to last version by Steveoc 86). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:56, 8 October 2007 by Vsmith (talk | contribs) (Reverted edits by 72.83.170.2 (talk) to last version by Steveoc 86)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Dinosaur (disambiguation).

| Dinosaurs Temporal range: 230.0–65.5 Ma PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N Triassic – Cretaceous (excluding Aves) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeletons of Tyrannosaurus (left) and Apatosaurus (right) at the American Museum of Natural History. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Sauropsida |

| Subclass: | Diapsida |

| Infraclass: | Archosauromorpha |

| Superorder: | Dinosauria * Owen, 1842 |

| Orders & Suborders | |

Dinosaurs were vertebrate animals that dominated terrestrial ecosystems for over 160 million years, first appearing approximately 230 million years ago. At the end of the Cretaceous Period, 65 million years ago, a catastrophic extinction event ended the dominance of dinosaurs on land. One group of dinosaurs is known to have survived to the present day: taxonomists believe modern birds are direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs.

Since the first dinosaur fossils were recognized in the early nineteenth century, mounted dinosaur skeletons have become major attractions at museums around the world. Dinosaurs have become a part of world culture and remain consistently popular among children and adults. They have been featured in best-selling books and films, and new discoveries are regularly covered by the media.

The term dinosaur is sometimes used informally to describe other prehistoric reptiles, such as the pelycosaur Dimetrodon, the winged pterosaurs, and the aquatic ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs and mosasaurs, although none of these were dinosaurs.

What is a dinosaur?

Definition

The taxon Dinosauria was formally named in 1842 by English palaeontologist Richard Owen, who used it to refer to the "distinct tribe or sub-order of Saurian Reptiles" that were then being recognized in England and around the world. The term is derived from the Greek words δεινός (deinos meaning "terrible", "fearsome", or "formidable") and σαύρα (saura meaning "lizard" or "reptile"). Though the taxonomic name has often been interpreted as a reference to dinosaurs' teeth, claws, and other fearsome characteristics, Owen intended it merely to evoke their size and majesty.

Dinosaurs were an extremely varied group of animals; according to a 2006 study, over 500 dinosaur genera have been identified with certainty so far, and the total number of genera preserved in the fossil record has been estimated at around 1,850, nearly 75% of which remain to be discovered. An earlier study predicted that about 3,400 dinosaur genera existed, including many which would not have been preserved in the fossil record. Some were herbivorous, others carnivorous. Some dinosaurs were bipeds, some were quadrupeds, and others, such as Ammosaurus and Iguanodon, could walk just as easily on two or four legs. Regardless of body type, nearly all known dinosaurs were well-adapted for a predominantly terrestrial, rather than aquatic or aerial, habitat.

Distinguishing features of dinosaurs

While recent discoveries have made it more difficult to present a universally agreed-upon list of dinosaurs' distinguishing features, nearly all dinosaurs discovered so far share certain modifications to the ancestral archosaurian skeleton. Although some later groups of dinosaurs featured further modified versions of these traits, they are considered typical across Dinosauria; the earliest dinosaurs had them and passed them on to all their descendants. Such common structures across a taxonomic group are called synapomorphies.

Dinosaur synapomorphies include an elongated crest on the humerus, or upper arm bone, to accommodate the attachment of deltopectoral muscles; a shelf at the rear of the ilium, or main hip bone; a tibia, or shin bone, featuring a broad lower edge and a flange pointing out and to the rear; and an ascending projection on the astragalus, one of the ankle bones, which secures it to the tibia.

A variety of other skeletal features were shared by many dinosaurs. However, because they were either common to other groups of archosaurs or were not present in all early dinosaurs, these features are not considered to be synapomorphies. Such shared features include a diapsid skull bearing two pairs of holes in the temporal region; holes in the snout and lower jaw (two characteristics shared by other archosaurs); loss of the skull's postfrontal bone; a long neck incorporating an S-shaped curve; an elongated scapula, or shoulder blade; forelimbs shorter and lighter than hind limbs, coupled to asymmetrical hands; a sacrum composed of three or more fused vertebrae; and an acetabulum, or hip socket, with a hole at the center of its inside surface.

The open, or "perforate", hip joint described above had significant implications for dinosaur movement and behavior. Most notably, it allowed dinosaur hind limbs to be "underslung", or situated directly beneath the animals' bodies; this, in turn, allowed dinosaurs to stand erect in a manner similar to modern mammals, but distinct from most other reptiles, whose limbs sprawl out to either side. Vertical limb configuration also enabled dinosaurs to breathe easily while moving, which likely permitted stamina and activity levels that surpassed those of "sprawling" reptiles.

Phylogenetic definition

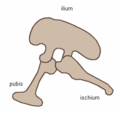

Under phylogenetic taxonomy, dinosaurs are usually defined as all descendants of the most recent common ancestor of Triceratops and modern birds. It has also been suggested that Dinosauria be defined as all the descendants of the most recent common ancestor of Megalosaurus and Iguanodon, because these were two of the three genera cited by Richard Owen when he recognized the Dinosauria. They are divided into Ornithischia (bird-hipped) and Saurischia (lizard-hipped), depending upon pelvic structure. Ornithischian dinosaurs had a four-pronged pelvic configuration, incorporating a caudally-directed (rear-pointing) pubis bone with (most commonly) a forward-pointing process. By contrast, the pelvic structure of saurischian dinosaurs was three-pronged, and featured a pubis bone directed cranially, or forwards, only. Ornithischia includes all taxa sharing a more recent common ancestor with Triceratops than with Saurischia, while Saurischia includes those taxa sharing a more recent common ancestor with birds than with Ornithischia.

There is an almost universal consensus among paleontologists that birds are the descendants of theropod dinosaurs. Using the strict cladistical definition that all descendants of a single common ancestor are related, modern birds are dinosaurs and dinosaurs are, therefore, not extinct. Modern birds are classified by most paleontologists as belonging to the subgroup Maniraptora, which are coelurosaurs, which are theropods, which are saurischians, which are dinosaurs.

However, referring to birds as 'avian dinosaurs' and to all other dinosaurs as 'non-avian dinosaurs' is cumbersome. Birds are still referred to as birds, at least in popular usage and among ornithologists. It is also technically correct to refer to birds as a distinct group under the older Linnaean classification system, which accepts paraphyletic taxa that exclude some descendants of a single common ancestor. Paleontologists mostly use cladistics, which classifies birds as dinosaurs, but some biologists of the older generation do not.

For clarity, this article will use 'dinosaur' as a synonym for 'non-avian dinosaur', and 'bird' as a synonym for 'avian dinosaur' (meaning any animal that evolved from the common ancestor of Archaeopteryx and modern birds). The term 'non-avian dinosaur' will be used for emphasis as needed.

Size

While the evidence is incomplete, it is clear that, as a group, dinosaurs were large. Even by dinosaur standards, the sauropods were gigantic. For much of the dinosaur era, the smallest sauropods were larger than anything else in their habitat, and the largest were an order of magnitude more massive than anything else that has since walked the Earth. Giant prehistoric mammals such as the Indricotherium and the Columbian mammoth were dwarfed by the giant sauropods, and only a handful of modern aquatic animals approach or surpass them in size — most notably the blue whale, which reaches up to 190,000 kg (209 tons) and over 30 m (100 ft) in length.

Most dinosaurs, however, were much smaller than the giant sauropods. Current evidence suggests that dinosaur average size varied through the Triassic, early Jurassic, late Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. According to paleontologist Bill Erickson, estimates of median dinosaur weight range from 500 kg to 5 tonnes; a recent study of 63 dinosaur genera yielded an average weight greater than 850 kg — comparable to the weight of a grizzly bear — and a median weight of nearly 2 tons, or about as much as a giraffe. This contrasts sharply with the size of modern mammals; on average, mammals weigh only 863 grams, or about as much as a large rodent. The smallest dinosaur was bigger than two-thirds of all current mammals; the majority of dinosaurs were bigger than all but 2% of living mammals.

Largest and smallest dinosaurs

Only a tiny percentage of animals ever fossilize, and most of these remain buried in the earth. Few of the specimens that are recovered are complete skeletons, and impressions of skin and other soft tissues are rare. Rebuilding a complete skeleton by comparing the size and morphology of bones to those of similar, better-known species is an inexact art, and reconstructing the muscles and other organs of the living animal is, at best, a process of educated guesswork. As a result, scientists will probably never be certain of the largest and smallest dinosaurs.

The tallest and heaviest dinosaur known from good skeletons is Brachiosaurus brancai (also known as Giraffatitan). Its remains were discovered in Tanzania between 1907–12. Bones from multiple similarly-sized individuals were incorporated into the skeleton now mounted and on display at the Humboldt Museum of Berlin; this mount is 12 m (38 ft) tall, 22.5 m (74 ft) long, and would have belonged to an animal that weighed between 30,000–60,000 kg (33–66 short tons). The longest complete dinosaur is the 27 m (89 ft) long Diplodocus, which was discovered in Wyoming in the United States and displayed in Pittsburgh's Carnegie Natural History Museum in 1907.

There were larger dinosaurs, but knowledge of them is based entirely on a small number of fragmentary fossils. Most of the largest herbivorous specimens on record were all discovered in the 1970s or later, and include the massive Argentinosaurus, which may have weighed 80,000–100,000 kg (88–121 tons); the longest, the 40 m (130 ft) long Supersaurus; and the tallest, the 18 m (60 ft) Sauroposeidon, which could have reached a sixth-floor window. The longest of them all may have been Amphicoelias fragillimus, known only from a now lost partial vertebral neural arch described in 1878. Extrapolating from the illustration of this bone, the animal may have been 58 m (190 ft) long and weighed over 120,000 kg (132 tons), heavier than all known dinosaurs except possibly the poorly known Bruhathkayosaurus, which could have weighed 175,000–220,000 kg (193–243 tons). The largest known carnivorous dinosaur was Spinosaurus, reaching a length of 16–18 meters (53–60 ft), and weighing in at 9 tons. Other large meat-eaters included Giganotosaurus, Mapusaurus, Tyrannosaurus rex and Carcharodontosaurus.

Not including modern birds, the smallest dinosaurs known were about the size of a crow or a chicken. The theropods Microraptor and Parvicursor were both under 60 cm (2 ft) in length.

Behavior

Interpretations of dinosaur behavior are generally based on the pose of body fossils and their habitat, computer simulations of their biomechanics, and comparisons with modern animals in similar ecological niches. As such, the current understanding of dinosaur behavior relies on speculation, and will likely remain controversial for the foreseeable future. However, there is general agreement that some behaviors which are common in crocodiles and birds, dinosaurs' closest living relatives, were also common among dinosaurs.

The first direct evidence of herding behavior was the 1878 discovery of 31 Iguanodon dinosaurs which were thought to have perished together in Bernissart, Belgium, after they fell into a deep, flooded sinkhole and drowned. Despite the deposition of those skeletons being now regarded as more gradual, other, well supported, mass death sites were subsequently discovered. Those, along with multiple trackways, suggest that herd or pack behavior was common in many dinosaur species. Trackways of hundreds or even thousands of herbivores indicate that duck-bills (hadrosaurids) may have moved in great herds, like the American Bison or the African Springbok. Sauropod tracks document that these animals traveled in groups composed of several different species, at least in Oxford, England, and others kept their young in the middle of the herd for defense according to trackways at Davenport Ranch, Texas. Dinosaurs may have congregated in herds for defense, for migratory purposes, or to provide protection for their young.

Jack Horner's 1978 discovery of a Maiasaura ("good mother dinosaur") nesting ground in Montana demonstrated that parental care continued long after birth among the ornithopods. There is also evidence that other Cretaceous-era dinosaurs, like the Patagonian sauropod Saltasaurus (1997 discovery), had similar nesting behaviors, and that the animals congregated in huge nesting colonies like those of penguins. The Mongolian maniraptoran Oviraptor was discovered in a chicken-like brooding position in 1993, which may mean it was covered with an insulating layer of feathers that kept the eggs warm. Trackways have also confirmed parental behavior among sauropods and ornithopods from the Isle of Skye in northwestern Scotland. Nests and eggs have been found for most major groups of dinosaurs, and it appears likely that dinosaurs communicated with their young, in a manner similar to modern birds and crocodiles.

The crests and frills of some dinosaurs, like the marginocephalians, theropods and lambeosaurines, may have been too fragile to be used for active defense, so they were likely used for sexual or aggressive displays, though little is known about dinosaur mating and territorialism. The nature of dinosaur communication also remains enigmatic, and is an active area of research. For example, recent evidence suggests that the hollow crests of the lambeosaurines may have functioned as resonance chambers used for a wide range of vocalizations.

From a behavioral standpoint, one of the most valuable dinosaur fossils was discovered in the Gobi Desert in 1971. It included a Velociraptor attacking a Protoceratops, proving that dinosaurs did indeed attack and eat each other. While cannibalistic behavior among theropods is no surprise, this too was confirmed by tooth marks from Madagascar in 2003.

Based on current fossil evidence only a single dinosaur, Oryctodromeus cubicularis, shows adaptations suggestive of a partially fossorial lifestyle, and relatively few were arboreal, most notably the primitive dromaeosaurids such as Microraptor. Since the later mammalian radiation in the Cenozoic produced numerous burrowing and tree-climbing species, e.g., rodents and primates, the lack of evidence for a similar radiation of species among the dinosaurs is somewhat surprising. Because most dinosaur species seem to have relied on land-based locomotion, a good understanding of how dinosaurs moved on the ground is key to models of dinosaur behavior; the science of biomechanics, in particular, has provided significant insight in this area. For example, studies of the forces exerted by muscles and gravity on dinosaurs' skeletal structure have investigated how fast dinosaurs could run, whether diplodocids could create sonic booms via whip-like tail snapping, whether giant theropods had to slow down when rushing for food to avoid fatal injuries, and whether sauropods could float.

Evolution of dinosaurs

Dinosaurs diverged from their archosaur ancestors approximately 230 million years ago during the Middle to Late Triassic period, roughly 20 million years after the Permian-Triassic extinction event wiped out an estimated 95% of all life on Earth. Radiometric dating of fossils from the early dinosaur genus Eoraptor establishes its presence in the fossil record at this time. Paleontologists believe Eoraptor resembles the common ancestor of all dinosaurs; if this is true, its traits suggest that the first dinosaurs were small, bipedal predators. The discovery of primitive, dinosaur-like ornithodirans such as Marasuchus and Lagerpeton in Argentinian Middle Triassic strata supports this view; analysis of recovered fossils suggests that these animals were indeed small, bipedal predators.

The first few lines of primitive dinosaurs diversified rapidly through the rest of the Triassic period; dinosaur species quickly evolved the specialized features and range of sizes needed to exploit nearly every terrestrial ecological niche. During the period of dinosaur predominance, which encompassed the ensuing Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, nearly every known land animal larger than 1 meter in length was a dinosaur.

The Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event, which occurred approximately 65 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous period, caused the extinction of all dinosaurs except for the line that had already given rise to the first birds. Other diapsid species related to the dinosaurs also survived the event.

Study of dinosaurs

Knowledge about dinosaurs is derived from a variety of fossil and non-fossil records, including fossilized bones, feces, trackways, gastroliths, feathers, impressions of skin, internal organs and soft tissues. Many fields of study contribute to our understanding of dinosaurs, including physics, chemistry, biology, and the earth sciences (of which paleontology is a sub-discipline).

Dinosaur remains have been found on every continent on Earth, including Antarctica. Numerous fossils of identical and closely related dinosaur species have been found on different continents, in accordance with the generally-accepted theory that all land masses were once connected in a super-continent called Pangaea.

The "dinosaur renaissance"

Main article: Dinosaur renaissanceThe field of dinosaur research has enjoyed a surge in activity that began in the 1970s and is ongoing. This was triggered, in part, by John Ostrom's discovery of Deinonychus, an active, vicious predator that may have been warm-blooded, in marked contrast to the then-prevailing image of dinosaurs as sluggish and cold-blooded. Vertebrate paleontology, arguably the primary scientific discipline involved in dinosaur research, has become a global science. Major new dinosaur discoveries have been made by paleontologists working in previously unexploited regions, including India, South America, Madagascar, Antarctica, and most significantly in China (the amazingly well-preserved feathered dinosaurs in China have further consolidated the link between dinosaurs and their conjectured living descendants, modern birds). The widespread application of cladistics, which rigorously analyzes the relationships between biological organisms, has also proved tremendously useful in classifying dinosaurs. Cladistic analysis, among other modern techniques, helps to compensate for an often incomplete and fragmentary fossil record.

Classification

Main article: Dinosaur classificationDinosaurs (including birds) are archosaurs, like modern crocodilians. Archosaurs' diapsid skulls have two holes, called temporal fenestrae, located where the jaw muscles attach. Most reptiles (including birds) are diapsids; mammals, with only one temporal fenestra, are called synapsids; and turtles, with no temporal fenestra, are anapsids. Anatomically, dinosaurs share many other archosaur characteristics, including teeth that grow from sockets rather than as direct extensions of the jawbones. Within the archosaur group, dinosaurs are differentiated most noticeably by their gait. Dinosaur legs extend directly beneath the body, whereas the legs of lizards and crocodylians sprawl out to either side. All dinosaurs were land animals.

Many other types of reptiles lived at the same time as the dinosaurs. Some of these are commonly, but incorrectly, thought of as dinosaurs, including plesiosaurs (which are not closely related to the dinosaurs) and pterosaurs, which developed separately from reptilian ancestors in the late Triassic period.

Collectively, dinosaurs are usually regarded as a superorder or an unranked clade. They are divided into two orders, the Saurischia and the Ornithischia, on the basis of their hip structure. Saurischians ('lizard-hipped', from the Greek sauros (σαυρος) meaning 'lizard' and ischion (ισχιον) meaning 'hip joint') are dinosaurs that originally retained the hip structure of their ancestors. They include all the theropods (bipedal carnivores) and sauropods (long-necked herbivores). Ornithischians ('bird-hipped', from the Greek ornitheios (ορνιθειος) meaning 'of a bird' and ischion (ισχιον) meaning 'hip joint') is the other dinosaurian order, most of which were quadrupedal herbivores. (NB: the terms "lizard hip" and "bird-hip" are misnomers — birds evolved from dinosaurs with "lizard hips".)

-

Saurischian pelvis structure (left side)

Saurischian pelvis structure (left side)

- Tyrannosaurus pelvis (showing saurischian structure - left side) Tyrannosaurus pelvis (showing saurischian structure - left side)

-

Ornithischian pelvis structure (left side).

Ornithischian pelvis structure (left side).

- Edmontosaurus pelvis (showing ornithischian structure - left side) Edmontosaurus pelvis (showing ornithischian structure - left side)

The following is a simplified classification of dinosaur families. A more detailed version can be found at List of dinosaur classifications.

The dagger (†) is used to indicate taxa that are extinct.

Order Saurischia

- †Infraorder Herrerasauria

- Suborder Theropoda

- †Superfamily Coelophysoidea

- †Infraorder Ceratosauria

- Family Ceratosauridae

- Family Abelisauridae

- Clade Tetanurae

- †Superfamily Spinosauroidea

- Family Megalosauridae

- Family Spinosauridae

- †Infraorder Carnosauria

- Clade Coelurosauria

- †Superfamily Tyrannosauroidea

- †Infraorder Ornithomimosauria

- †Infraorder Segnosauria

- †Infraorder Oviraptorosauria

- †Infraorder Deinonychosauria

- Family Dromaeosauridae

- Family Troodontidae

- †Superfamily Spinosauroidea

- †Suborder Sauropodomorpha

- Infraorder Prosauropoda

- Family Riojasauridae

- Family Plateosauridae

- Family Massospondylidae

- Infraorder Sauropoda

- Family Anchisauridae

- Family Melanorosauridae

- Family Blikanasauridae

- Family Vulcanodontidae

- Family Cetiosauridae

- Family Omeisauridae

- Clade Turiasauria

- Clade Neosauropoda

- Superfamily Diplodocoidea

- Family Camarasauridae

- Family Brachiosauridae

- Superfamily Titanosauroidea

- Infraorder Prosauropoda

†Order Ornithischia

- Family Fabrosauridae

- Suborder Thyreophora

- Family Scelidosauridae

- Infraorder Stegosauria

- Infraorder Ankylosauria

- Family Nodosauridae

- Family Ankylosauridae

- Suborder Cerapoda

- Family Heterodontosauridae

- Infraorder Ornithopoda

- Family Hypsilophodontidae

- Family Iguanodontidae

- Superfamily Hadrosauroidea

- Clade Marginocephalia

- Infraorder Pachycephalosauria

- Infraorder Ceratopsia

- Family Psittacosauridae

- Family Protoceratopsidae

- Family Ceratopsidae

Areas of debate

Physiology

Main article: Physiology of dinosaurs

A vigorous debate on the subject of temperature regulation in dinosaurs has been ongoing since the 1960s. Originally, scientists broadly disagreed as to whether dinosaurs were capable of regulating their body temperatures at all. More recently, dinosaur endothermy has become the consensus view, and debate has focused on the mechanisms of temperature regulation.

After dinosaurs were discovered, paleontologists first posited that they were ectothermic creatures: "terrible lizards" as their name suggests. This supposed cold-bloodedness implied that dinosaurs were relatively slow, sluggish organisms, comparable to modern reptiles, which need external sources of heat in order to regulate their body temperature. Dinosaur ectothermy remained a prevalent view until Robert T. "Bob" Bakker, an early proponent of dinosaur endothermy, published an influential paper on the topic in 1968.

Modern evidence indicates that dinosaurs thrived in cooler temperate climates, and that at least some dinosaur species must have regulated their body temperature by internal biological means (perhaps aided by the animals' bulk). Evidence of endothermism in dinosaurs includes the discovery of polar dinosaurs in Australia and Antarctica (where they would have experienced a cold, dark six-month winter), the discovery of dinosaurs whose feathers may have provided regulatory insulation, and analysis of blood-vessel structures that are typical of endotherms within dinosaur bone. Skeletal structures suggest that theropods and other dinosaurs had active lifestyles better suited to an endothermic cardiovascular system, while sauropods exhibit fewer endothermic characteristics. It is certainly possible that some dinosaurs were endothermic while others were not. Scientific debate over the specifics continues.

Complicating the debate is the fact that warm-bloodedness can emerge based on more than one mechanism. Most discussions of dinosaur endothermy tend to compare them to average birds or mammals, which expend energy to elevate body temperature above that of the environment. Small birds and mammals also possess insulation, such as fat, fur, or feathers, which slows down heat loss. However, large mammals, such as elephants, face a different problem because of their relatively small ratio of surface area to volume (Haldane's principle). This ratio compares the volume of an animal with the area of its skin: as an animal gets bigger, its surface area increases more slowly than its volume. At a certain point, the amount of heat radiated away through the skin drops below the amount of heat produced inside the body, forcing animals to use additional methods to avoid overheating. In the case of elephants, they are hairless, and have large ears which increase their surface area, and have behavioral adaptations as well (such as using the trunk to spray water on themselves and mud wallowing). These behaviors increase cooling through evaporation.

Large dinosaurs would presumably have had to deal with similar issues; their body size suggest they lost heat relatively slowly to the surrounding air, and so could have been what are called inertial homeotherms, animals that are warmer than their environments through sheer size rather than through special adaptations like those of birds or mammals. However, so far this theory fails to account for the vast number of dog- and goat-sized dinosaur species which made up the bulk of the ecosystem during the Mesozoic Era.

Feathered dinosaurs and the origin of birds

Main article: Feathered dinosaurs Main article: Origin of birdsBirds and non-avian dinosaurs share many features. Birds share over a hundred distinct anatomical features with theropod dinosaurs, which are generally accepted to have been their closest ancient relatives.

Feathers

Archaeopteryx, the first good example of a "feathered dinosaur", was discovered in 1861. The initial specimen was found in the Solnhofen limestone in southern Germany, which is a lagerstätte, a rare and remarkable geological formation known for its superbly detailed fossils. Archaeopteryx is a transitional fossil, with features clearly intermediate between those of modern reptiles and birds. Brought to light just two years after Darwin's seminal The Origin of Species, its discovery spurred the nascent debate between proponents of evolutionary biology and creationism. This early bird is so dinosaur-like that, without a clear impression of feathers in the surrounding rock, at least one specimen was mistaken for Compsognathus.

Since the 1990s, a number of additional feathered dinosaurs have been found, providing even stronger evidence of the close relationship between dinosaurs and modern birds. Most of these specimens were unearthed in Liaoning province, northeastern China, which was part of an island continent during the Cretaceous period. Though feathers have been found only in the lagerstätte of the Yixian Formation and a few other places, it is possible that non-avian dinosaurs elsewhere in the world were also feathered. The lack of widespread fossil evidence for feathered non-avian dinosaurs may be due to the fact that delicate features like skin and feathers are not often preserved by fossilization and thus are absent from the fossil record.

A recent development in the debate centers around the discovery of impressions of "protofeathers" surrounding many dinosaur fossils. Said protofeathers suggest that the tyrannosauroids may have been feathered. However, others claim that these protofeathers are simply the result of the decomposition of collagenous fiber that underlaid the dinosaurs' integument.

The feathered dinosaurs discovered so far include Beipiaosaurus, Caudipteryx, Dilong, Microraptor, Protarchaeopteryx, Shuvuuia, Sinornithosaurus, Sinosauropteryx, and Jinfengopteryx. Dinosaur-like birds like Confuciusornis, which are anatomically closer to modern avians, have also been discovered. All of these specimens come from the same formation in northern China. The dromaeosauridae family in particular seems to have been heavily feathered, and at least one dromaeosaurid, Cryptovolans, may have been capable of flight.

Skeleton

Because feathers are often associated with birds, feathered dinosaurs are often touted as the missing link between birds and dinosaurs. However, the multiple skeletal features also shared by the two groups represent the more important link for paleontologists. Furthermore, it is increasingly clear that the relationship between birds and dinosaurs, and the evolution of flight, are more complex topics than previously realized. For example, while it was once believed that birds evolved from dinosaurs in one linear progression, some scientists, most notably Gregory S. Paul, conclude that dinosaurs such as the dromaeosaurs may have evolved from birds, losing the power of flight while keeping their feathers in a manner similar to the modern ostrich and other ratites.

Comparison of bird and dinosaur skeletons, as well as cladistic analysis, strengthens the case for the link, particularly for a branch of theropods called maniraptors. Skeletal similarities include the neck, pubis, wrist (semi-lunate carpal), arm and pectoral girdle, shoulder blade, clavicle and breast bone.

Reproductive biology

A discovery of features in a Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton recently provided even more evidence that dinosaurs and birds evolved from a common ancestor and, for the first time, allowed paleontologists to establish the sex of a dinosaur. When laying eggs, female birds grow a special type of bone in their limbs. This medullary bone, which is rich in calcium, forms a layer inside the hard outer bone that is used to make eggshells. The presence of endosteally-derived bone tissues lining the interior marrow cavities of portions of the Tyrannosaurus rex specimen's hind limb suggested that T. rex used similar reproductive strategies, and revealed the specimen to be female.

A dinosaur embryo was found without teeth, suggesting that some parental care was required to feed the young dinosaur. It is also possible that the adult dinosaurs regurgitated into a young dinosaur's mouth to provide sustenance, a behavior that is also characteristic of numerous modern bird species.

Lungs

Large meat-eating dinosaurs had a complex system of air sacs similar to those found in modern birds, according to an investigation which was led by Patrick O'Connor of Ohio University. The lungs of theropod dinosaurs (carnivores that walked on two legs and had birdlike feet) likely pumped air into hollow sacs in their skeletons, as is the case in birds. "What was once formally considered unique to birds was present in some form in the ancestors of birds", O'Connor said. The study was funded in part by the National Science Foundation.

Heart and sleeping posture

Modern computerized tomography (CT) scans of a dinosaur chest cavity (conducted in 2000) found the apparent remnants of complex four-chambered hearts, much like those found in today's mammals and birds. The idea is controversial within the scientific community, coming under-fire for bad anatomical science or simply wishful thinking. A recently discovered troodont fossil demonstrates that the dinosaurs slept like certain modern birds, with their heads tucked under their arms. This behavior, which may have helped to keep the head warm, is also characteristic of modern birds.

Gizzard

Another piece of evidence that birds and dinosaurs are closely related is the use of gizzard stones. These stones are swallowed by animals to aid digestion and break down food and hard fibres once they enter the stomach. When found in association with fossils, gizzard stones are called gastroliths. Because a particular stone could have been swallowed at one location before being carried to another during migration, paleontologists sometimes use the stones found in dinosaur stomachs to establish possible migration routes.

Evidence for Paleocene dinosaurs

In 2002, paleontologists Zielinski and Budahn reported the discovery of a single hadrosaur leg bone fossil in the San Juan Basin, New Mexico and described it as evidence of Paleocene dinosaurs. The formation in which the bone was discovered has been dated to the early Paleocene epoch approximately 64.5 million years ago. If the bone was not re-deposited into that stratum by weathering action, it would provide evidence that some dinosaur populations may have survived at least a half million years into the Cenozoic Era.

Soft tissue and DNA

One of the best examples of soft tissue impressions in a fossil dinosaur was discovered in Petraroia, Italy. The discovery was reported in 1998, and described the specimen of a small, very young coelurosaur, Scipionyx samniticus. The fossil includes portions of the intestines, colon, liver, muscles, and windpipe of this immature dinosaur.

In the March 2005 issue of Science, Dr. Mary Higby Schweitzer and her team announced the discovery of flexible material resembling actual soft tissue inside a 68-million-year-old Tyrannosaurus rex leg bone from the Hell Creek Formation in Montana. After recovery, the tissue was rehydrated by the science team.

When the fossilized bone was treated over several weeks to remove mineral content from the fossilized bone marrow cavity (a process called demineralization), Schweitzer found evidence of intact structures such as blood vessels, bone matrix, and connective tissue (bone fibers). Scrutiny under the microscope further revealed that the putative dinosaur soft tissue had retained fine structures (microstructures) even at the cellular level. The exact nature and composition of this material, and the implications of Dr. Schweitzer's discovery, are not yet clear; study and interpretation of the material is ongoing.

The successful extraction of ancient DNA from dinosaur fossils has been reported on two separate occasions, but upon further inspection and peer review, neither of these reports could be confirmed. However, a functional visual peptide of a theoretical dinosaur has been inferred using analytical phylogenetic reconstruction methods on gene sequences of related modern species such as reptiles and birds. In addition, several proteins have putatively been detected in dinosaur fossils, including hemoglobin.

Even if dinosaur DNA could be reconstructed, it would be exceedingly difficult to clone and "grow" dinosaurs using current technology since no closely related species exist to provide zygotes or a suitable environment for embryonic development.

Extinction theories

Main article: Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction eventThe sudden mass extinction of non-avian dinosaurs, an event that occurred approximately 65 million years ago, is one of the most intriguing mysteries in paleontology. Many other groups of animals also became extinct at this time, including ammonites (nautilus-like mollusks), mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, herbivorous turtles and crocodiles, most birds, and many groups of mammals. The nature of the event that caused this mass extinction has been extensively studied since the 1970s; at present, several related theories are supported by paleontologists. Though the general consensus is that an impact event was the primary cause of dinosaur extinction, some scientists cite other possible causes, or support the idea that a confluence of several factors was responsible for the sudden disappearance of dinosaurs from the fossil record.

Asteroid collision

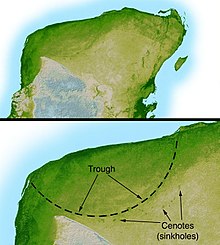

The asteroid collision theory, which was first proposed by Walter Alvarez in the late 1970s, links the extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period to a bolide impact approximately 65.5 million years ago. Alvarez proposed that a sudden increase in iridium levels, recorded around the world in the period's rock stratum, was direct evidence of the impact. The bulk of the evidence now suggests that a 5–15 km wide bolide hit in the vicinity of the Yucatán Peninsula, creating the 170 km-wide Chicxulub Crater and triggering the mass extinction. Scientists are not certain whether dinosaurs were thriving or declining before the impact event. Some scientists propose that the meteorite caused a long and unnatural drop in Earth's atmospheric temperature, while others claim that it would have instead created an unusual heat wave.

Although the speed of extinction cannot be deduced from the fossil record alone, various models suggest that the extinction was extremely rapid. The consensus among scientists who support this theory is that the impact caused extinctions both directly (by heat from the meteorite impact) and also indirectly (via a worldwide cooling brought about when matter ejected from the impact crater reflected thermal radiation from the sun).

In September of 2007, U.S. researchers led by William Bottke of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, and Czech scientists used computer simulations to identify the probable source of the Chicxulub impact. They calculated a 90% probability that a giant asteroid named Baptistina (about 160 kilometres (100 miles) in diameter) orbiting in the asteroid belt which lies between Mars and Jupiter), was struck by a smaller unnamed asteroid about 55 kilometres (35 miles) in diameter about 160 million years ago. The impact shattered Baptistina, creating a cluster which still exists today as the Baptistina family. Calculations indicate that some of the fragments were sent hurtling into earth-crossing orbits, one of which was the 10-km-wide (6-mile-wide) meteorite which struck Mexico's Yucatan peninsula 65 million years ago, creating the Chicxulub crater (175 kilometres wide (110 miles)). The researchers also calculated a 70% probability that an earlier-arriving fragment (108 million years BP) struck the Moon, creating the Tycho crater. Philippe Claeys of Vrije Universiteit Brussel in Belgium stated that the findings were "clear evidence that the solar system is a violent environment and that collisions taking place in the asteroid belt can have major repercussions for the evolution of life on Earth."

Multiple collisions—the Oort cloud

While similar to Alvarez's impact theory (which involved a single asteroid or comet), this theory proposes that "passages of the solar companion star Nemesis through the Oort comet cloud would trigger comet showers." One or more of these objects then collided with the Earth at approximately the same time, causing the worldwide extinction. As with the impact of a single asteroid, the end result of this comet bombardment would have been a sudden drop in global temperatures, followed by a protracted cool period.

Environment changes

Before the mass extinction of the dinosaurs, the release of volcanic gasses during the formation of the Deccan traps "contributed to an apparently massive global warming. Some data point to an average rise in temperature of eight degrees Celsius (a change of 14.4 degrees Fahrenheit) in the last half million years before the impact ."

At the peak of the dinosaur era, there were no polar ice caps, and sea levels are estimated to have been from 100 to 250 meters (330 to 820 feet) higher than they are today. The planet's temperature was also much more uniform, with only 25 degrees Celsius separating average polar temperatures from those at the equator. On average, atmospheric temperatures were also much warmer; the poles, for example, were 50 °C warmer than today.

The atmosphere's composition during the dinosaur era was vastly different as well. Carbon dioxide levels were up to 12 times higher than today's levels, and oxygen formed 32 to 35% of the atmosphere, as compared to 21% today. However, by the late Cretaceous, the environment was changing dramatically. Volcanic activity was decreasing, which led to a cooling trend as levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide dropped. Oxygen levels in the atmosphere also started to fluctuate and would ultimately fall considerably. Some scientists hypothesize that climate change, combined with lower oxygen levels, might have led directly to the demise of many species. If the dinosaurs had respiratory systems similar to those commonly found in modern birds, it may have been particularly difficult for them to cope with reduced respiratory efficiency, given the enormous oxygen demands of their very large bodies.

History of discovery

Dinosaur fossils have been known for millennia, although their true nature was not recognized. The Chinese, whose own word for dinosaur is konglong (恐龍, or "terrible dragon"), considered them to be dragon bones and documented them as such. For example, Hua Yang Guo Zhi, a book written by Zhang Qu during the Western Jin Dynasty, reported the discovery of dragon bones at Wucheng in Sichuan Province. Villagers in central China have been digging up dinosaur bones for decades, thinking they were from dragons, to make traditional medicine. In Europe, dinosaur fossils were generally believed to be the remains of giants and other creatures killed by the Great Flood.

Megalosaurus was the first dinosaur to be formally described, in 1677, when part of a bone was recovered from a limestone quarry at Cornwell near Oxford, England. This bone fragment was identified correctly as the lower extremity of the femur of an animal larger than anything living in modern times. The second dinosaur genus to be identified, Iguanodon, was discovered in 1822 by the English geologist Gideon Mantell, who recognized similarities between his fossils and the bones of modern iguanas. Two years later, the Rev William Buckland, a professor of geology at Oxford University, unearthed more fossilized bones of Megalosaurus and became the first person to describe dinosaurs in a scientific journal.

The study of these "great fossil lizards" soon became of great interest to European and American scientists, and in 1842 the English paleontologist Richard Owen coined the term "dinosaur". He recognized that the remains that had been found so far, Iguanodon, Megalosaurus and Hylaeosaurus, shared a number of distinctive features, and so decided to present them as a distinct taxonomic group. With the backing of Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, the husband of Queen Victoria, Owen established the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, London, to display the national collection of dinosaur fossils and other biological and geological exhibits.

In 1858, the first known American dinosaur was discovered, in marl pits in the small town of Haddonfield, New Jersey (although fossils had been found before, their nature had not been correctly discerned). The creature was named Hadrosaurus foulkii. It was an extremely important find; Hadrosaurus was the first nearly complete dinosaur skeleton found and it was clearly a bipedal creature. This was a revolutionary discovery as, until that point, most scientists had believed dinosaurs walked on four feet, like other lizards. Foulke's discoveries sparked a wave of dinosaur mania in the United States.

Dinosaur mania was exemplified by the fierce rivalry between Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, both of whom raced to be the first to find new dinosaurs in what came to be known as the Bone Wars. The feud probably originated when Marsh publicly pointed out that Cope's reconstruction of an Elasmosaurus skeleton was flawed; Cope had inadvertently placed the plesiosaur's head at what should have been the animal's tail end. The fight between the two scientists lasted for over 30 years, ending in 1897 when Cope died after spending his entire fortune on the dinosaur hunt. Marsh 'won' the contest primarily because he was better funded through a relationship with the US Geological Survey. Unfortunately, many valuable dinosaur specimens were damaged or destroyed due to the pair's rough methods; for example, their diggers often used dynamite to unearth bones (a method modern paleontologists would find appalling). Despite their unrefined methods, the contributions of Cope and Marsh to paleontology were vast; Marsh unearthed 86 new species of dinosaur and Cope discovered 56, for a total of 142 new species. Cope's collection is now at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, while Marsh's is on display at the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University.

Since 1897, the search for dinosaur fossils has extended to every continent, including Antarctica. The first Antarctic dinosaur to be discovered, the ankylosaurid Antarctopelta oliveroi, was found on Ross Island in 1986, although it was 1994 before an Antarctic species, the theropod Cryolophosaurus ellioti, was formally named and described in a scientific journal.

Current dinosaur "hot spots" include southern South America (especially Argentina) and China. China in particular has produced many exceptional feathered dinosaur specimens due to the unique geology of its dinosaur beds, as well as an ancient arid climate particularly conducive to fossilization.

Dinosaurs in culture

Main article: Cultural depictions of dinosaurs

By human standards, dinosaurs were creatures of fantastic appearance and often enormous size. As such, they have captured the public imagination and become an enduring part of human culture. Only three decades after the first scientific descriptions of dinosaur remains, the famous dinosaur sculptures were erected in Crystal Palace Park in London. These sculptures excited the public so strongly that smaller replicas were sold, one of the first examples of tie-in merchandising. Since Crystal Palace, dinosaur exhibitions have opened at parks and museums around the world, both catering to, and reinforcing, the public interest. Dinosaur popularity has long had a reciprocal effect on dinosaur science, as well. The competition between museums for public attention led directly to the Bone Wars waged between Marsh and Cope, each striving to return with more spectacular fossil remains than the other, and the resulting contribution to dinosaur science was enormous.

Dinosaurs hold an integral place in modern culture. The word "dinosaur" itself has entered the English lexicon as an expression describing anything that is impractically large, slow-moving, or obsolete, bound for extinction. The public preoccupation with dinosaurs led to their inevitable entrance into worldwide popular culture. Beginning with a passing mention of Megalosaurus in the first paragraph of Charles Dickens' Bleak House in 1852, dinosaurs have been featured in a broad array of fictional works. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's 1912 book The Lost World, the iconic 1933 film King Kong, the 1954 introduction of Godzilla and its many subsequent sequels, the best-selling 1990 novel Jurassic Park by Michael Crichton and its 1993 film version, briefly the highest-grossing film of all time, are just a few prominent examples of the long tradition of dinosaurs in fiction. Non-fiction authors, including some prominent paleontologists, have also sought to take advantage of dinosaur popularity, especially among children, to educate readers about dinosaurs in particular and science in general. Dinosaurs are ubiquitous in advertising, with numerous companies seeking to utilize dinosaurs to sell their own products or to characterize their rivals as slow-moving or obsolete.

Religious views

Main article: Creationist perspectives on dinosaursVarious religious groups have views about dinosaurs that differ from those held by scientists, usually due to conflicts with creation stories in their scriptures. However, the scientific community does not accept these religiously-inspired interpretations of dinosaurs.

See also

- Dinosaur classification

- Fossils

- List of dinosaurs

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- Living dinosaurs

- Prehistoric life

- Prehistoric reptiles

Notes and references

- Owen, R. (1842). "Report on British Fossil Reptiles." Part II. Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Plymouth, England.

- Farlow, J.O., and Brett-Surman, M.K. (1997). Preface. In: Farlow, J.O., and Brett-Surman, M.K. (eds.). The Complete Dinosaur. Indiana University Press: Bloomington and Indianapolis, ix-xi. ISBN 0-253-33349-0

- Wang, S.C., and Dodson, P. (2006). Estimating the Diversity of Dinosaurs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 103:37, pp. 13601–13605.

- Russell, Dale A. (1995). China and the lost worlds of the dinosaurian era. Historical Biology 10: 3-12.

- Benton, M.J. (2004). Origin and relationships of dinosaurs. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., and Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria (second edition). University of California Press:Berkeley, 7–19. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- Holtz, Jr., T.R. (2000). Classification and evolution of the dinosaur groups. In: Paul, G.S. (ed.). The Scientific American Book of Dinosaurs. St. Martin's Press:New York, 140–168. ISBN 0-312-26226-4.

- Langer, M.C., Abdala, F., Richter, M., and Benton, M.J. (1999). A sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Upper Triassic (Carnian) of southern Brazil. Comptes Rendus de l'Academie des Sciences, Paris: Sciences de la terre et des planètes 329:511–517.

- ^ Benton, M.J. (2004). Vertebrate Paleontology (second edition). Blackwell Publishers:London, xii-452. ISBN 0-632-05614-2.

- Padian, K., and May, C.L. (1993). "The earliest dinosaurs." pp. 379–381 in S.G. Lucas and M. Morales, eds., The Nonmarine Triassic. Albuquerque: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 3.

- Olshevsky, G. (2000). "An annotated checklist of dinosaur species by continent." Mesozoic Meanderings, 3: 1–157

- Padian, K. (2004). Basal Avialae. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., and Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria (second edition). University of California Press:Berkeley, 210–231. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- Dinosaur size varied in different periods Working hypothesis for body size.

- Origin of Dinosaurs and Mammals - Erickson Source of Erickson quote.

- Colbert, E.H. (1968). Men and Dinosaurs: The Search in Field and Laboratory. E. P. Dutton & Company:New York, vii + 283 p. ISBN 0140212884.

- Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation (pdf). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - dal Sasso, C., Maganuco, S., Buffetaut, E., and Mendez, M.A. (2006). New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod Spinosaurus, with remarks on its sizes and affinities. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25(4):888–896.

- Johan Yans, Jean Dejax, Denise Pons, Christian Dupuis, Philippe Taquet.(2005) Palaeontological and geodynamical implications of the palynological dating of the wealden facies sediments of Bernissart (Mons Basin, Belgium). C. R. Palevol 4 (2005) 135–150.

- Deposition of Iguanodon skeletons occurred in at least 3 different events.

- Day, J.J. and Upchurch, P. (2002). Sauropod Trackways, Evolution, and Behavior. Science 296:1659. See commentary on the article

- Horner J.R., Makela R., 1979. Nest of Juveniles Provides Evidence of Family-Structure Among Dinosaurs, Nature 282 (5736): 296–298

- Oviraptor nesting Oviraptor nests or Protoceratops?

- Dinosaur family tracks Footprints show maternal instinct after leaving the nest.

- Joined forever in death The discovery of two fossil dinosaurs entangled together proved many theories.

- Cannibalistic Dinosaur The mystery of a dinosaur cannibal.

- Rogers, R.R., Krause, D.W. and Rogers, K.C. (2003). Cannibalism in the Madagascan dinosaur Majungatholus atopus. Nature 422:515-518.See commentary on the article.

- Gait and Dinosaur speed Gait and his formula on estimating a dinosaur's speed.

- Calculate your own Dinosaur speed More on Gait and his speed calculations.

- Douglas, K. and Young, S. (1998). The dinosaur detectives. New Scientist 2130:24. See commentary on the article.

- Hecht, J. (1998). The deadly dinos that took a dive. New Scientist 2130. See commentary on the article.

- Henderson, D.M. (2003). Effects of stomach stones on the buoyancy and equilibrium of a floating crocodilian: A computational analysis. Canadian Journal of Zoology 81:1346–1357. See commentary on the article.

- Citation for Permian/Triassic extinction event, percentage of animal species that went extinct. See commentary

- Another citation for P/T event data. See commentary

- Hayward, T. (1997). The First Dinosaurs. Dinosaur Cards. Orbis Publishing Ltd. D36040612.

- Sereno, P.C., C.A. Forster, R.R. Rogers, and A.M. Monetta. 1993. Primitive dinosaur skeleton from Argentina and the early evolution of Dinosauria. Nature 361:64–66.

- ^ Dal Sasso, C. and Signore, M. (1998). Exceptional soft-tissue preservation in a theropod dinosaur from Italy. Nature 292:383–387. See commentary on the article

- Schweitzer, M.H., Wittmeyer, J.L. and Horner, J.R. (2005). Soft-Tissue Vessels and Cellular Preservation in Tyrannosaurus rex. Science 307:1952–1955. See commentary on the article

- Evans, J. (1998). Ultimate Visual Dictionary - 1998 Edition. Dorling Kindersley Books. 66–69. ISBN 1-871854-00-8.

- Parsons, K.M. (2001). Drawing Out Leviathan. Indiana University Press. 22–48. ISBN 0-253-33937-5.

- Mayr, G., Pohl, B. and Peters, D.S. (2005). A Well-Preserved Archaeopteryx Specimen with Theropod Features. Science 310:1483-1486.See commentary on the article.

- Wellnhofer, P. (1988). Ein neuer Exemplar von Archaeopteryx. Archaeopteryx 6:1–30.

- Xu, et al. "Basal tyrannosauroids from China and evidence for protofeathers in tyrannosauroids." Nature. 2004 October 7; 431(7009):680-4. PMID: 15470426

- Feduccia, et al. "Do feathered dinosaurs exist? Testing the hypothesis on neontological and paleontological evidence." J Morphol. 2005 Nov; 266(2):125-66. PMID: 16217748

- O'Connor, P.M. and Claessens, L.P.A.M. (2005). "Basic avian pulmonary design and flow-through ventilation in non-avian theropod dinosaurs". Nature 436:253.

- Fisher, P. E., Russell, D. A., Stoskopf, M. K., Barrick, R. E., Hammer, M. & Kuzmitz, A. A. (2000). Cardiovascular evidence for an intermediate or higher metabolic rate in an ornithischian dinosaur. Science 288, 503–505.

- Hillenius, W. J. & Ruben, J. A. (2004). The evolution of endothermy in terrestrial vertebrates: Who? when? why? Physiological and Biochemical Zoology 77, 1019–1042.

- Dinosaur with a Heart of Stone. T. Rowe, E. F. McBride, P. C. Sereno, D. A. Russell, P. E. Fisher, R. E. Barrick, and M. K. Stoskopf (2001) Science 291, 783

- Xu, X. and Norell, M.A. (2004). A new troodontid dinosaur from China with avian-like sleeping posture. Nature 431:838-841.See commentary on the article.

- Fassett, J, R.A. Zielinski, & J.R. Budahn. (2002). Dinosaurs that did not die; evidence for Paleocene dinosaurs in the Ojo Alamo Sandstone, San Juan Basin, New Mexico. In: Catastrophic events and mass extinctions; impacts and beyond. (Eds. Koeberl, C. & K. MacLeod): Special Paper - Geological Society of America 356: 307–336.

- Schweitzer, M.H., Wittmeyer, J.L. and Horner, J.R. (2005). Soft-Tissue Vessels and Cellular Preservation in Tyrannosaurus rex. Science 307:1952–1955. Also covers the Reproduction Biology paragraph in the Feathered dinosaurs and the bird connection section. See commentary on the article

- Wang, H., Yan, Z. and Jin, D. (1997). Reanalysis of published DNA sequence amplified from Cretaceous dinosaur egg fossil. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 14:589–591. See commentary on the article.

- Chang, B.S.W., Jönsson, K., Kazmi, M.A., Donoghue, M.J. and Sakmar, T.P. (2002). Recreating a Functional Ancestral Archosaur Visual Pigment. Molecular Biology and Evolution 19:1483–1489. See commentary on the article.

- Embery, et al. "Identification of proteinaceous material in the bone of the dinosaur Iguanodon." Connect Tissue Res. 2003; 44 Suppl 1:41-6. PMID: 12952172

- Schweitzer, et al. "Heme compounds in dinosaur trabecular bone." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997 Jun 10; 94(12):6291–6. PMID: 9177210

- ^ (November 2000). Earthwatch :6–13.

- Yahoo.com, Distant space collision meant doom for dinosaurs

- ^ Koeberl, C. and MacLeod, K.G. (2002). Catastrophic Events and Mass Extinctions. Geological Society of America. ISBN 0-8137-2356-6.

- Production Manager: Yolanda Ayres. "What Really Killed the Dinosaurs". BBC Horizon.

- See entry on The Campanian Diversity Explosion at Dinodata (registration required, free): The effect climate change may have had on the extinction of the Dinosaurs

- Dino-Era Earth Had Polar Ice, Low Sea Level, Study Says Sea levels during the dinosaur era; National Geographic; November 29, 2005

- Dong Zhiming (1992). Dinosaurian Faunas of China. China Ocean Press, Beijing. ISBN 3-540-52084-8.

- "Dinosaur bones 'used as medicine'". BBC News. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-06.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Williams, P. (1997). The Battle of the Bones. Dinosaur Cards. Orbis Publishing Ltd. D36040607.

- Torrens, H.S. (1993). "The dinosaurs and dinomania over 150 years." Modern Geology 18(2): 257-286.

- Breithaupt, Brent H. (1997) "First golden period in the USA." In: Currie, Philip J. & Padian, Kevin (Eds.). The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 347-350.

- "Definition of dinosaur" Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary. Accessed 26 May 2007.

- "London. Michaelmas term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln's Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets, as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborne Hill." From page 1 of Dickens, Charles J.H. (1852). Bleak House. London: Bradbury & Evans.

- Glut, Donald F, and Brett-Surman, Michael K. (1997) "Dinosaurs and the media." In: Farlow, James O. & Brett-Surman, Michael K. (Eds.). The Complete Dinosaur Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Pp. 675-697

- Kitcher, Philip (1983). Abusing Science: The Case Against Creationism. MIT Press. p. 213. 978-0-262-61037-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Dawkins, Richard (1996). The Blind Watchmaker: Why the Evidence of Evolution Reveals a Universe Without Design. W.W. Norton. p. 400. 978-0393315707.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

General references

- Kevin Padian, and Philip J. Currie. (1997). Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-226810-5. (Articles are written by experts in the field).

- Paul, Gregory S. (2000). The Scientific American Book of Dinosaurs. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-26226-4.

- Paul, Gregory S. (2002). Dinosaurs of the Air: The Evolution and Loss of flight in Dinosaurs and Birds. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6763-0.

- Weishampel, David B. (2004). The Dinosauria. University of California Press; 2nd edition. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

External links

Listen to this article(2 parts, 42 minutes)

- For children

- Zoom Dinosaurs (www.enchantedlearning.com) From Enchanted Learning. Kid's site, info pages, theories, history.

- Images

- The Art Gallery of The Dinosauricon, hosting over 2000 images from many different artists working in different styles.

- The Grave Yard, featuring skeletal restorations of a variety of prehistoric animals.

- Skeletal Drawing Professional restorations of numerous dinosaurs, and discussions of dinosaur anatomy.

- Popular

- Dinosaurs & other extinct creatures: From the Natural History Museum, a well illustrated dinosaur directory.

- Dinosaurnews (www.dinosaurnews.org) The dinosaur-related headlines from around the world. Recent news on dinosaurs, including finds and discoveries, lots of links.

- Dinosauria From UC Berkeley Museum of Paleontology Detailed information - scroll down for menu.

- LiveScience.com All about dinosaurs, with current featured articles.

- Dino Russ's Lair hosts a large collection of dinosaur-related links.

- Technical

- Palaeontologia Electronica From Coquina Press. Online technical journal.

- Dinobase A searchable dinosaur database, from the University of Bristol, with dinosaur lists, classification, pictures, and more.

- DinoData (www.dinodata.org) Technical site, essays, classification, anatomy.

- Dinosauria On-Line (www.dinosauria.com) Technical site, essays, pronunciation, dictionary.

- The Dinosauricon By T. Michael Keesey. Technical site, cladogram, illustrations and animations.

- Thescelosaurus! By Justin Tweet. Includes a cladogram and small essays on each relevant genera and species.

- Dinosauromorpha Cladogram From Palaeos. A detailed amateur site about all things paleo.

- The Dinosaur Encyclopaedia, an extensive overview of genera-based dinosaur information from 1999 and before.

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: