This is an old revision of this page, as edited by DanaUllman (talk | contribs) at 05:29, 28 November 2007 (Shang never divulged the results from the 21 high quality homeopathic studies and the 9 high quality conventional studies. Junk science at its worst.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 05:29, 28 November 2007 by DanaUllman (talk | contribs) (Shang never divulged the results from the 21 high quality homeopathic studies and the 9 high quality conventional studies. Junk science at its worst.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

Homeopathy (also homœopathy or homoeopathy; from the Greek ὅμοιος, hómoios, "similar" + πάθος, páthos, "suffering" or "disease") is a controversial form of complementary and alternative medicine first used in the late 18th century by German physician Samuel Hahnemann. His early work was advanced by later homeopaths such as James Tyler Kent, but Hahnemann's most famous textbook The Organon of the Healing Art remains in wide use today. The legal status of homeopathy varies from country to country, but homeopathic remedies are not tested and regulated under the same laws as conventional drugs. Usage is also variable and ranges from only two percent of people in Britain and the United States using homeopathy in any one year, to India, where homeopathy now forms part of traditional medicine and is used by approximately 15 percent of the population.

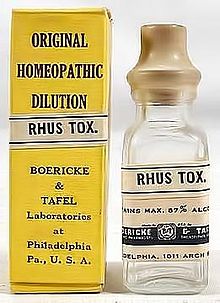

Homeopathic remedies are based on substances that, in undiluted form, cause symptoms similar to the disease they aim to treat. These substances are then diluted in a process of serial dilution, with shaking at each stage, that homeopaths believe removes side-effects but retains therapeutic powers - even past the point where no molecules of the original substance are likely to remain. Hahnemann proposed that this process aroused and enhanced "spirit-like medicinal powers held within a drug". Sets of remedies used in homeopathy are recorded in homeopathic materia medica, with practitioners selecting treatments according to consultations that try to produce a picture of both the physical and psychological state of the patient.

Claims for the efficacy of homeopathy are unsupported by the collected weight of scientific and clinical studies. This lack of evidence supporting its efficacy, along with its stance against modern scientific ideas, have caused, in the words of a recent medical review, "...homeopathy to be regarded as placebo therapy at best and quackery at worst." These studies are complicated by that fact that trials on homeopathy are generally flawed in design, and earlier analyses that suggested positive effects might not be completely due to placebo could not completely control for the combination of publication bias and the low quality of these trials. Homeopaths are also accused of giving 'false hope' to patients who might otherwise seek effective conventional treatments. Many homeopaths advise against standard medical procedures such as vaccination, and some homeopaths even advise against the use of anti-malarial drugs.

History

Precursors

The "system of similars" emphasized in homeopathy was first described by doctors of the vitalist school of medicine, including the controversial Renaissance physician Paracelsus. Prior to the conception of homeopathy, Austrian physician Anton Freiherr von Störck and Scottish physician John Brown also held medical beliefs resembling those of Samuel Hahnemann, who is credited with the development of modern homeopathy in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

At the time of the inception of homeopathy, mainstream medicine employed such measures as bloodletting and purging, the use of laxatives and enemas, and the administration of complex mixtures, such as Theriac, which was made from 64 substances including opium, myrrh, and viper's flesh. Such measures often worsened symptoms and sometimes proved fatal. While the virtues of these treatments had been extolled for centuries, Hahnemann rejected such methods as irrational and unadvisable. Instead, he favored the use of single drugs at lower doses and promoted an immaterial, vitalistic view of how living organisms function, believing that diseases have spiritual, as well as physical causes. (At the time, vitalism was part of mainstream science; in the twentieth century, however, medicine discarded vitalism, with the development of microbiology, the germ theory of disease, and advances in chemistry.) Hahnemann also advocated various lifestyle improvements to his patients, including exercise, diet, and cleanliness.

Hahnemann's conception of homeopathy

Samuel Hahnemann conceived of homeopathy while translating a medical treatise by Scottish physician and chemist William Cullen into German. He was skeptical of Cullen’s explanation of cinchona bark’s mechanism of action in treating malaria, so he decided to test its effects by taking it himself. Upon ingesting the bark, he experienced fever, shivering and joint pain, symptoms similar to those of malaria, which the bark was ordinarily used to treat. From this, Hahnemann came to believe that all effective drugs produce symptoms in healthy individuals similar to those of the diseases that they are intended to treat. This later became known as the "law of similars", the most important concept of homeopathy. The term "homeopathy" was coined by Hahnemann and first appeared in print in 1807, although he began outlining his theories of "medical similars" in a series of articles and monographs in 1796.

Hahnemann began to test the symptoms which substances can produce, a procedure which would later become known as "proving". The time-consuming tests required subjects to clearly record all of their symptoms as well as the ancillary conditions under which they appeared. Hahnemann used this data to find suitable substances for the treatment of particular diseases. The first collection of provings was published in 1805 and a second collection of 65 remedies appeared in the Materia Medica Pura in 1810. Hahnemann believed that large doses of things that caused similar symptoms would only aggravate illness, and so he advocated extreme dilutions of the substances. He devised a technique for making dilutions that he believed would preserve a substance's therapeutic properties while removing its harmful effects. He gathered and published a complete overview of his new medical system in his 1810 book, The Organon of the Healing Art, whose 6th edition, published in 1921, is still used by homeopaths today.

Rise to popularity and early criticism

During the 19th century homeopathy grew in popularity: in 1830, the first homeopathic schools opened, and throughout the 19th century dozens of homeopathic institutions appeared in Europe and the United States. Because of mainstream medicine's reliance on blood-letting and untested, often dangerous medicines, patients of homeopaths often had better outcomes than those of mainstream doctors. Homeopathic treatments, even if ineffective, would almost surely cause no harm, making the users of homeopathic medicine less likely to be killed by the medicine that was supposed to be helping them. The relative success of homeopathy in the 18th century may have led to the abandonment of the ineffective and harmful treatments of bloodletting and purging and to have begun the move towards more effective, scientific medicine.

In the early 19th century, homeopathy began to be criticized: Sir John Forbes, physician to Queen Victoria, said the extremely small doses of homeopathy were regularly derided as useless, laughably ridiculous and "an outrage to human reason." Professor Sir James Young Simpson said of the highly diluted drugs: "no poison, however strong or powerful, the billionth or decillionth of which would in the least degree affect a man or harm a fly." Nineteenth century American physician and author Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. was also a vocal critic of homeopathy and published an essay in 1842 entitled Homœopathy, and its Kindred Delusions. The last school in the U.S. exclusively teaching homeopathy closed down in 1920.

General philosophy

Homeopathy is a vitalist philosophy in that it regards diseases and sickness to be caused by disturbances in a hypothetical vital force or life force in humans and that these disturbances manifest themselves as unique symptoms. Homeopathy contends that the vital force has the ability to react and adapt to internal and external causes, which homeopaths refer to as the "law of susceptibility". The law of susceptibility states that a negative state of mind can attract hypothetical disease entities called "miasms" to invade the body and produce symptoms of diseases, However, Hahnemann rejected the notion of a disease as a separate thing or invading entity and insisted that it was always part of the "living whole".

Law of similars

Hahnemann observed from his experiments with Cinchona bark, used as a treatment of malaria, that the side effects he experienced from the quinine in the Cinchona bark were similar to the symptoms of malaria. He reasoned that treatments for diseases must produce symptoms similar to of those disease being treated when taken by healthy individuals. From this Hahnemann conceived of the "law of similars", otherwise known as "like cures like" (Template:Lang-la). Hahnemann believed that by inducing artificial symptoms of a disease, the artificial symptoms would create another disturbance in the vital force thus pushing out the old disturbance and that the body would naturally recover from the artificially induced disturbance. The basic idea is that to cure a person suffering from an illness, one should administer a dilute dose of a substance that produces the same symptoms of the illness being treated in healthy individuals.

Miasms and disease

Hahnemann found as early as 1816 that his patients who he treated through homeopathy still suffered from chronic diseases that he was unable to cure. In 1828, he introduced the concept of miasms, which he regarded as underlying causes for many known diseases. A miasm is often defined by homeopaths as an imputed "peculiar morbid derangement of our vital force." Hahnemann associated each miasm with specific diseases, with each miasm seen as the root cause of several diseases. According to Hahnemann, initial exposure to miasms causes local symptoms, such as skin or venereal diseases, but if these symptoms are suppressed by medication, the cause goes deeper and begins to manifest itself as diseases of the internal organs. Homeopathy contends that treating diseases by directly opposing their symptoms, as is sometimes done in conventional medicine, is not so effective because all "disease can generally be traced to some latent, deep-seated, underlying chronic, or inherited tendency." The underlying imputed miasm still remains, and deep-seated ailments can only be corrected by removing the deeper disturbance of the vital force.

Hahnemann's miasm theory remains disputed and controversial within homeopathy even in modern times. In 1978, Anthony Campbell, then a consultant physician at The Royal London Homeopathic Hospital, criticized statements by George Vithoulkas claiming that syphilis, when treated with antibiotics, would develop into secondary and tertiary syphilis with involvement of the central nervous system. This conflicts with scientific studies, which indicate that penicillin treatment produces a complete cure of syphilis in more than 90% of cases. Campbell described this as "a thoroughly irresponsible statement which could mislead an unfortunate layman into refusing orthodox treatment" and said that it was not an isolated case, but part of a lengthy section arguing against conventional medicine. This echoes the idea in homeopathy that using medication to suppress the symptoms of a disease would only drive the underlying disease deeper into the body.

Originally Hahnemann presented only three miasms, of which the most important was "psora" (Greek for itch), described as being related to any itching diseases of the skin, supposed to be derived from suppressed scabies, and claimed to be the foundation of many further disease conditions. Hahnemann claimed psora to be the cause of such diseases as epilepsy, cancer, jaundice, deafness, and cataracts. Since Hahnemann's time, other miasms have been proposed, some replacing one or more of psora's proposed functions, including tubercular miasms and cancer miasms.

Development of remedies

Dilution and succussion

In producing treatments for diseases, homeopaths use a process called "dynamization" or "potentization" where the remedy is diluted into alcohol or water and then vigorously shaken by ten hard strikes against an elastic body in a process called "succussion". Hahnemann thought that the use of remedies which present symptoms similar to those of disease in healthy individuals would only intensify the symptoms and exacerbate the condition, so he advocated the dilution of the remedies to the point the symptoms were no longer experienced. During the process of potentization, homeopaths believe that the vital energy of the diluted substance is activated and its energy released by vigorous shaking of the substance. For this purpose, Hahnemann had a saddle maker construct a special wooden striking board covered in leather on one side and stuffed with horsehair. Insoluble solids, such as quartz and oyster shell, are diluted by grinding them with lactose (trituration).

Three potency scales are in regular use in homeopathy. Hahnemann pioneered and always favored the centesimal or "C scale", diluting a substance 1 part in a 100 of diluent at each stage. A 2C dilution is one where a substance is diluted to one part in one hundred, then one part of that diluted solution is diluted to one part in one hundred. This works out to one part of the original solution to ten thousand parts (100x100) of diluent. A 6C dilution repeats the process six times, ending up with one part in 1,000,000,000,000. (100x100x100x100x100x100, or 100) Other dilutions follow the same pattern. In homeopathy, a solution is described as higher potency the more dilute it is. Higher potencies - i.e. more dilute substances - are considered to be stronger deep-acting remedies.

Hahnemann advocated 30C dilutions for most purposes (a dilution by a factor of 10) and a common homeopathic treatment for the flu is a 200C dilution of duck liver, called Oscillococcinum in homeopathy. Comparing these levels of dilution to the number of molecules present in the initial solution, a 12C solution contains on average only about one molecule of the original substance. The chances of a single molecule of the original substance remaining in a 15C dilution would be roughly 1 in 2 million, and less than one in a billion billion billion billion (10) for a 30C solution. For a perspective on these numbers, there are in the order of 10 molecules of water in an Olympic size swimming pool and if such a pool were filled with a 15C homeopathic remedy, to expect to get a single molecule from the original substance, one would need to swallow 1% of the volume of such a pool, or roughly 25 metric tons of water.

For more perspective, 1ml of a solution which has gone through a 30C dilution would have been diluted into a volume of water equal to that of a cube of 1,000,000,000,000,000,000 meters per side, or about 106 light years. Thus, homeopathic remedies of the standard dilutions contain, with overwhelming probability, only water (or alcohol). Practitioners of homeopathy believe that this water retains some 'essential property' of the original substance, due to the shaking after each dilution. Hahnemann believed that the dynamization or shaking of the solution caused a "spirit like" healing force to be released from within the substance. He thought that even after every molecule of the previous substance has been removed from the water, the spiritual healing force still remained.

Some homeopaths developed a decimal scale (D or X), diluting the substance to ten times its original volume each stage. The D or X scale dilution is therefore half that of the same value of the C scale; for example, "12x" is the same level of dilution as "6C". Hahnemann never used this scale but it was very popular throughout the 19th century and still is in Europe. This potency scale appears to have been introduced in the 1830s by the American homeopath, Dr. Constantine Hering. In the last ten years of his life Hahnemann also developed a quintamillesimal (Q) or LM scale diluting the drug 1 part in 50,000 parts of diluent. A Q scale dilution is 2.35 times that of a C scale one, for example "20Q" is the same potency as "47C".

Not all homeopaths advocate extremely high dilutions. Many of the early homeopaths were originally doctors and generally tended to use lower dilutions such as "3x" or "6x", rarely going beyond "12x". A good example of this approach is that of Dr. Richard Hughes, who dismissed the extremely high dilutions as unnecessary. This was the dominant pattern in Europe throughout the 1820s to 1930s, but in America many practitioners developed and preferred the higher dilutions. This trend became especially exemplified by James Tyler Kent and dominated US homeopathy from the 1850s until its demise in the 1940s. The split between lower and higher dilutions also followed ideological lines with the former stressing pathology and a strong link to conventional medicine, while the latter emphasized vital force, miasms and a spiritual take on sickness. From a modern regulatory viewpoint, any product that contains detectable levels of active ingredients cannot be classified as a homeopathic remedy.

Provings

In order to determine which specific remedies could be used to treat which diseases, Hahnemann experimented on himself for several years as well as with patients. His experiments did not initially consist of giving remedies to the sick, because he thought that the most similar remedy, by virtue of its ability to induce symptoms similar to the disease itself, would make it impossible to determine which symptoms came from the remedy and which from the disease itself. Therefore, sick people were excluded from the provings. The method used for determining which remedies were suitable for specific diseases was called "proving". A homeopathic proving is the method by which the profile of a homeopathic remedy is determined. The word 'proving' derives from the German word 'Prüfung' meaning 'test'.

During the process of proving, Hahnemann used healthy volunteers who were given remedies, often in molecular doses, and the resulting symptoms were compiled by observers into a "Drug Picture". During the process the volunteers were observed for months at a time and were made to keep extensive journals detailing all of their symptoms at specific times during the day. During the tests volunteers were forbidden from consuming coffee, tea, spices, or wine. They were also not allowed to play chess, because Hahnemann considered it to be "too exciting", however they were allowed to drink beer and were encouraged to moderately exercise. After the experiments were over, Hahnemann made the volunteers offer their hands and take an oath swearing that what they reported in their journals was the truth, at which time he would interrogate them extensively concerning their symptoms.

Provings have been described as important in the development of the clinical trial, due to their early use of simple control groups, systematic and quantitative procedures, and some of the first application of statistics in medicine. The lengthy records of self-experimentation by homeopaths have occasionally proven useful in the development of modern drugs: For example, evidence nitroglycerin might be useful as a treatment for angina was discovered by looking through homeopathic provings, though homeopaths themselves never used it for that purpose at that time. The first recorded provings were published by Hahnemann in his 1796 Essay on a New Principle. His Fragmenta de viribus (1805) contained the results of 27 provings, and his 1810 Materia Medica Pura contained 65. 217 remedies underwent provings for James Tyler Kent's 1905 Lectures on Homoeopathic Materia Medica, and newer substances are continually added to contemporary versions.

Repertory

A compilation of reports of many homeopathic provings is known as a homeopathic materia medica. In practice the usefulness of such a compilation is limited because a practitioner does not need to look up the symptoms for a particular remedy, but rather to explore the remedies for a particular symptom. This need is filled by the homeopathic repertory, which is an index of symptoms, listing after each symptom those remedies that are associated with it. Repertories are often very extensive and may include data from clinical experience in addition to provings. There is often lively debate among the compilers of a repertory and interested practitioners over the veracity of a particular inclusion. The first symptomatic index of the homeopathic materia medica was arranged by Hahnemann. Soon after, one of his students Clemens von Bönninghausen, created the Therapautic Pocket Book, another homeopathic repertory. The first such Homeopathic Repertory was Dr. George Jahr's Repertory, published in 1835 in German and then again in 1838 in English and edited by Dr. Constantine Hering. This version was less focused on disease categories and would be the forerunner to Kent's later works. It consisted of three large volumes. Such Repertories increased in size and detail as time progressed.

Treatments

Homeopathic treatments generally begin with a detailed examinations of their patients' histories, including questions regarding their physical, mental and emotional states, their one's life circumstances and any physical/emotional illnesses. The homeopath then translates this information into a complex formula of mental and physical symptoms, including likes, dislikes, innate predispositions and even body type. The goal is to develop a comprehensive representation of each individual's overall health. This information can then be compared with similar established data in the drug provings found in the homeopathic materia medica. Assisted by further dialogs with the patient, the homeopath then aims to find the one drug most closely matching the 'symptom totality' of the patient. There are many methods for determining the most-similar remedy (the simillimum), and homeopaths sometimes disagree. This is partly due to the complexity of the "totality of symptoms" concept. That is, homeopaths do not use all symptoms, but decide which are the most characteristic. This subjective evaluation of case analysis relies on knowledge and experience of the homeopath doing the diagnosis.

Some diversity in approaches to treatments exists among homeopaths. So called "Classical" homeopathy generally involves detailed examinations of a patient's history and infrequent doses of a single remedy as the patient is monitored for improvements in symptoms. On the other hand, "clinical" homeopathy uses a range of approaches including combinations of remedies to "cover" the various symptoms of an illness, similar to conventional drug treatments.

Remedies

"Remedy" is a technical term used in homeopathy to refer to a substance prepared with a particular procedure and intended for treating patients. Homeopathic practitioners rely on two types of reference when prescribing remedies. The Homeopathic Materia Medicae which is comprised of alphabetical indexes of "drug pictures" organized by remedy and describe the symptom patterns associated with individual remedies. They also rely on homeopathic repertories which consist of indexes of symptoms of diseases and listing remedies associated with specific symptoms.

Homeopathy uses many animal, plant, mineral, and synthetic substances in its remedies. Examples include Natrum muriaticum (sodium chloride or table salt), Lachesis muta (the venom of the bushmaster snake), Opium, and Thyroidinum (thyroid hormone). Homeopaths also use treatments called nosodes (from the Greek nosos, disease) made from diseased or pathological products such as fecal, urinary, and respiratory discharges, blood, and tissue. Homeopathic remedy prepared from healthy specimens are called Sarcodes.

Some modern homeopaths have considered more esoteric substances, known as "imponderables" because they do not originate from a material but from electromagnetic energy presumed to have been "captured" by alcohol or lactose. Examples include X-rays, sunlight, and electricity. Recent ventures by homeopaths into even more esoteric substances include thunderstorms (prepared from collected rainwater). Today there are about 3,000 different remedies commonly used in homeopathy. Some homeopaths also use techniques that are regarded by other practitioners as controversial. These include paper remedies, where the substance and dilution are written on a piece of paper and either pinned to the patient's clothing, put in their pocket, or placed under a glass of water that is then given to the patient, as well as the use of radionics to prepare remedies. Such practices have been strongly criticized by classical homeopaths as unfounded, speculative and verging upon magic and superstition.

Isopathy

Isopathy is a therapy derived from homeopathy and was invented by Johann Joseph Wilhelm Lux in the 1830s. Isopathy differs from homeopathy in general in that the remedies are made up either from things that cause the disease, or from products of the disease, such as pus. Many so-called "homeopathic vaccines" are a form of isopathy.

Tautopathy

Tautopathy is a practice of alternative medicine that is similar to homeopathy in that it uses very diluted substances to treat illness. However, tautopathy does not rely on the law of similars, as homeopathy does. According to practitioners of Tautopathy, dilute solutions of lead and arsenic can cause the body to secrete excess amounts of these toxic metals.

Flower remedies

Flower remedies are produced by placing flowers in water and exposing them to sunlight. The most famous of these are the Bach flower remedies, which were developed by the homeopath Edward Bach. The relationship between these remedies and homeopathy is controversial. On the one hand, the proponents of these remedies share homeopathy's vitalist world-view and the remedies are claimed to act through the same hypothetical vital force. However, although many of the same plants are used as in homeopathy, flower remedies are used undiluted. There is no convincing scientific or clinical evidence for flower remedies being effective.

Veterinary homeopathy

Veterinary homeopathy is the term used to describe the treatment of animals with homeopathy. The idea of using homeopathy as a treatment for other animals dates back to the inception of homepathy as Hahnemann himself wrote and spoke of the use of homeopathy in animals other than humans. In the USA veterinary homeopathy is used by veterinarian members of the Academy for Veterinary Homeopathy and/or the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association. In the UK, veterinary surgeons who use homeopathy belong to the Faculty of Homeopathy and/or to the British Association of Homeopathic Veterinary Surgeons or BAHVS. Animals may only be treated by qualified veterinary surgeons in the UK and some other countries. Internationally, the body that supports and represents homeopathic veterinarians is the International Association for Veterinary Homeopathy or IAVH. The use of homeopathy in veterinary medicine is regarded as controversial, as there has been little scientific investigation and current research in the field is not of a high enough standard to provide reliable data. Other studies have also found that giving animals placebos can play active roles in influencing pet owners to believe in the effectiveness of the treatment when none exists.

Medical and scientific analysis and criticism

Homeopathy is unsupported by modern scientific research. The extreme dilutions used in homeopathic preparations usually leave none of the active ingredient (no atoms, ions or molecules) in the final product. The idea that any biological effects could be produced by these preparations is inconsistent with the observed dose-response relationships of conventional drugs. The proposed rationale for these extreme dilutions - that the water contains the "memory" or "vibration" from the diluted ingredient - is also counter to the accepted laws of chemistry and physics. Thus critics contend that any positive results obtained from homeopathic remedies are purely due to the placebo effect, where the patients subjective improvement of symptoms is based solely on the power of suggestion, due to the individual expecting or believing that it will work. Critics cite the lack of viable scientific studies for the effectiveness of homeopathic remedies as evidence that they are not effective and that any positive effects are due to the placebo effect. Critics also contend that homeopathy is inherently dangerous, because homeopaths offer a false hope to patients who could be getting proper treatment.

High dilutions

The extremely high dilutions in homeopathy have been a main point of criticism. Homeopaths believe that the methodical dilution of a substance, beginning with a 10% or lower solution and working downwards, with shaking after each dilution, produces a therapeutically active "remedy", in contrast to therapeutically inert water. However, homeopathic remedies are usually diluted to the point where there are no molecules from the original solution left in a dose of the final remedy. Since even the longest-lived noncovalent structures in liquid water at room temperature are only stable for a few picoseconds, critics have concluded that any effect that might have been present from the original substance can no longer exist. Furthermore, since water will have been in contact with millions of different substances throughout its history, critics point out that any glass of water is therefore an extreme dilution of almost any conceivable substance, and so by drinking water one would, according to homeopathic principles, receive treatment for every imaginable condition.

Homeopathy contends that higher dilutions (fewer potential molecules in each dose) result in stronger medicinal effects. This idea is inconsistent with the observed dose-response relationships of conventional drugs, where the effects are dependent on the concentration of the active ingredient in the body. This dose-response relationship has been confirmed in thousands of experiments on organisms as diverse as nematodes, rats and humans.

Physicist Robert L. Park, Ph.D., former executive director of the American Physical Society, has noted that "since the least amount of a substance in a solution is one molecule, a 30C solution would have to have at least one molecule of the original substance dissolved in a minimum of 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 molecules of water. This would require a container more than 30,000,000,000 times the size of the Earth." Park has also noted that "to expect to get even one molecule of the "medicinal" substance allegedly present in 30X pills, it would be necessary to take some two billion of them, which would total about a thousand tons of lactose plus whatever impurities the lactose contained." The laws of chemistry state that there is a limit to the dilution that can be made without losing the original substance altogether. This limit, which is related to Avogadro's number, corresponds to homeopathic potencies of 12C or 24X (1 part in 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000).

Clinical trials

The medical effectiveness of homeopathy has been a point of contention since its inception. One of the earliest studies concerning homeopathic medicine was sponsored by the British government during World War II in which volunteers tested the effectiveness of homeopathic remedies against diluted mustard gas burns. More recent controlled clinical trials on homeopathy have shown poor results, showing a slight to no difference between homeopathic remedies and placebo. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which analyze large groups of studies and draw conclusions based on the results as a whole have been used to test the effectiveness of homeopathy. Early meta-analyses investigating homeopathic remedies showed slightly positive results among the studies examined, however such studies have warned that it was impossible to draw conclusions due to low methodological quality and the unknown role of publication bias in the studies reviewed. A recent meta-analysis of clinical trials on the effectiveness of homeopathy has shown that earlier clinical trials showed signs of major weakness in methodology and reporting, and that homeopathy trials were less randomized and reported less on dropouts than other types of trials.

The medical effectiveness of homeopathy has been studied in detail since at least the 1980s. All large studies showing homeopathy to be effective for medical purposes have been methodologically flawed, and earlier studies showing positive results have been questioned. There have also been numerous landmark studies which have brought into question the validity of homeopathic treatments. In 2005 The Lancet medical journal published a meta-analysis of 110 placebo-controlled homeopathy trials and 110 matched conventional-medicine trials based upon the Swiss government's Program for Evaluating Complementary Medicine, or PEK. Critics cite numerous studies that show no evidence of homeopathy being effective beyond placebo, including a European Journal of Cancer study done in 2006. The study was a meta-analysis of six trials of homeopathic treatments for recovery from cancer therapy, including radio and chemotherapy done since 1985. Three of the trials included were randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trials. The conclusions of the study was that there was insufficient evidence to support using homeopathic therapy to treat cancer.

Since homeopathic remedies at dilutions higher than about D23 (10) contain no ingredients apart from the diluent (water, alcohol or sugar), there is no chemical basis for them to have any medicinal action. While some tests have suggested that homeopathic solutions of high dilution can have statistically significant effects on organic processes including the growth of grain, histamine release by leukocytes, and enzyme reactions, such studies are disputed since attempts to replicate them have failed. Newer randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials using high dilutions of substances such as Belladona also fail to find clinical effects of the substances.

Critics assert that the best standard for assessing efficacy and safety of health-care practices is evidence-based medicine because it is the expression of the scientific method in clinical medicine. They contend that systematic reviews with strict protocols are essential to establish the substantion of various therapies and that when homeopathy is tested in this way against specific diseases, it has failed to show any medical effectiveness. Systematic reviews conducted by the Cochrane Collaboration found no evidence that homeopathy is beneficial for asthma, dementia,Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). Systematic reviews conducted by other researchers found no evidence that homeopathy is beneficial for osteoarthritis, migraines or delayed-onset muscle soreness.

A notable controversy involved French immunologist Jacques Benveniste who in 1987 submitted a paper to the scientific journal Nature while working at INSERM. The paper purported to have discovered that basophils released histamine when exposed to a homeopathic dilution of anti-immunoglobulin E, a type of white blood cell. Nature, skeptical of the results, requested that the study be replicated in a separate laboratory under identical conditions. Upon replication in four separate laboratories the study was published. Still skeptical of the findings, Nature assembled an independent investigative team to determine the accuracy of the research. The team consisted of Nature editor and physicist Sir John Maddox, American scientific fraud investigator and chemist Walter Stewart, and skeptic and magician James Randi. After investigating the findings and methodology of the experiment, the team found that the experiments were "statistically ill-controlled", "interpretation has been clouded by the exclusion of measurements in conflict with the claim", and concluded "We believe that experimental data have been uncritically assessed and their imperfections inadequately reported." James Randi stated that he doubted that there had been any conscious fraud, however he stated that the researchers had allowed "wishful thinking" to influence their interpretation of the data.

Numerous health organizations such as UK's National Health Service, the American Medical Association, and the FASEB also contend that there is no convincing scientific evidence that would support the use of homeopathic treatments in medicine.

Safety issues

As homeopathic remedies usually contain often only water and/or alcohol, they are thought to be generally safe. Only in rare cases are the original ingredients present at detectable levels. However, in one case, a unusually undiluted (1:100 or "2X") solution of zinc gluconate, marketed as Zicam Nasal Spray, allegedly caused a small percentage of users to lose their sense of smell. There were 340 cases settled out of court for 12 million U.S. dollars.

However, critics of homeopathy have cited other concerns over homeopathic remedies, most seriously, cases of patients of homeopathy failing to receive proper treatment for diseases that could be diagnosed or cured with modern medicine. For instance, there have been surveys showing that homeopathic practitioners frequently advise their patients against receiving immunization for diseases. Modern homeopathic practitioners also use their own vaccines, which they refer to as "nosodes", and are created from dilutions of biological agents - including material such as vomit, feces or infected human tissues. While Hahnemann was opposed to such preparations, modern homeopaths frequently use them and there is no evidence to suggest they have any beneficial effects. Cases of homeopaths advising against the use of anti-malarial drugs have been identified. This puts visitors to the tropics who take this advice in severe danger, since homeopathic remedies are completely ineffective against the malaria parasite. Also, in one case in 2004, a homeopath instructed one of his patients to stop taking conventional medication for a heart condition, writing in his advice: "She just cannot take ANY drugs – I have suggested some homeopathic remedies. I feel confident that if she follows the advice she will regain her health." The patient suffered a fatal heart attack four months later, caused by this stoppage of her medication.

In 1978, Anthony Campbell, then a consultant physician at The Royal London Homeopathic Hospital, criticized statements made by George Vithoulkas to promote his homeopathic treatments. Vithoulkas stated that syphilis, when treated with antibiotics, would develop into secondary and tertiary syphilis with involvement of the central nervous system. Campbell described this as a thoroughly irresponsible statement which could mislead an unfortunate layman into refusing orthodox treatment. This claim echoes the idea that treating a disease with external medication used to treat the symptoms would only drive it deeper into the body and conflicts with scientific studies, which indicate that penicillin treatment produces a complete cure of syphilis in more than 90% of cases.

Critics also contend that it is inherently unethical to provide homeopathic remedies to patients when the effectiveness of homeopathy is clearly unproven. Critics also assert that all homeopathic patients or clients should be fully informed of the lack of convincing experimental support for the effectiveness of homeopathy, prior to being given the remedies. Critics also state that it is unethical to employ unsupported and unproven remedies such as homeopathy when modern alternatives are genuinely effective.

Prevalence and legal trends

Homeopathic medicine is fairly common in some countries while uncommon in others and is also highly regulated in some countries while fairly unregulated in others. Regulations vary in Europe depending on the country. In some countries, there are no specific legal regulations concerning the use of homeopathy, while in others, licenses or degrees in conventional medicine from accredited universities are required. In Austria and Germany, no specific regulations exist, while France and Denmark mandate licenses to diagnose any illness or dispense of any product whose purpose is to treat any illness. Some homeopathic treatment is covered by the national insurance coverage of several European countries, including France, the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Luxembourg. In other countries, such as Belgium, homeopathy is not covered. In Austria, public insurance requires scientific proof of effectiveness in order to reimburse medical treatments, but exceptions are made for homeopathy. Two countries which formerly offered homeopathy under their public health insurance schemes have withdrawn this privilege. At the start of 2004, homeopathic medications, with some exceptions, were no longer covered by German public health insurance, and in June 2005, the Swiss Government, after a 5-year trial, withdrew insurance coverage for homeopathy and four other complementary treatments, claiming that they did not meet efficacy and cost-effectiveness criteria, though additional insurance can be bought to cover such treatments provided by a medical doctor.

Outline of past prevalence in Great Britain

In Britain homeopathy was first established by Dr. Frederick Quin around 1827, although two Italian homeopathic doctors (Drs Romani and Roberta) had been employed two years previously by the Earl of Shrewsbury based at Alton Towers in North Staffordshire. Homeopathy in Britain quickly became the preferred medical treatment of the upper classes, as well as the aristocracy and retained an elite clientele, including members of the royal family.

At its peak in the 1870s, Britain had numerous homeopathic dispensaries and small hospitals as well as large busy hospitals in Liverpool, Birmingham, Glasgow, London and Bristol.

Contemporary prevalence

The largest organization of homeopaths in Britain, the Society of Homeopaths, was founded in 1978 and the Faculty of Homeopathy, which is based in London, has over 1,400 members and was incorporated by an Act of Parliament in 1950. According to a 2006 study, forty nine percent of Scottish medical practices prescribed homeopathic remedies. During the study period, 0.22% of patients were prescribed at least one homeopathic remedy, with children making up 16 percent of the population prescribed homeopathic remedies (0.22% of the total registered patients at that age). The study concluded that critical review of Homeopathy's role in the Scottish branch of the national health care system was needed. The NHS currently operates five homeopathic hospitals.

In Australia, according to one study, about 4.4% of Australian adults have used homeopathic remedies at least once in their lives and only about 1.2% sought help exclusively from homeopathic practitioners. In Canada, a study detailing the use of alternative medicines by children in Quebec found that 11% of the sample of 1911 children used alternative medicines and 25% of those who did use alternative medicines used homeopathy. The study also pointed out that homeopathy is more commonly used in children in Canada than in adults, 19% of whom used alternative medicine used homeopathy. Homeopathy is not officially recognized by Federal Food and Drug Act in Canada and physicians who choose to use alternative medicines such as Homeopathy must follow guidelines set by their province's College of Physicians and Surgeons. Provincial health care generally doesn't cover homeopathy.

Some countries in South America, such as Argentina, allow only professional doctors who are qualified and have graduated from a recognized medical school to practice homeopathy. Homeopathy has been regulated in other South American countries, such as Colombia, since the beginning of the 20th century. In Brazil, Homeopathy is included in the national health system and since 1991, physicians who want to practice homeopathy must complete 2,300 hours of education prior to receiving the proper licenses. In Mexico, Homeopathy is currently integrated into the national health care system. In 1985, a presidential decree established the first homeopathic school as well as regulations specifying training requirements for homeopathic doctors. In Mexico, of the individuals who use complementary alternative medicines, over 26% use Homeopathy.

In the United States homeopathy is much less common, where the percentage of people seeking homeopathic treatment declined from 3.4% in 1997 to 1.7% in 2002. Homeopathy was first established in the United States by Dr Hans Burch Gram in 1825 and rapidly gained popularity, partly because conventional medicine of the time was inherently dangerous and risky. The height of its influence was the end of the 19th century where hardly any city with over 50,000 people was without a homeopathic hospital. In 1890 there were 93 regular schools, 14 of them were fully homeopathic and 8 of them were eclectic and in 1900 there were 121 regular schools and 22 of them were homeopathic and 10 eclectic. The use of homeopathy in the United States among adults is about 0.3%. According to one study, in 1990, 0.7% of individuals used homeopathy in the past year of being questioned; in 1997, 3.4% had used homeopathy at least once in the previous year. According to the same study, of those who used homeopathy, 31.7% had seen a homeopathic practitioner in the past year in 1990 and the number dropped to 16.5 by 1997.

In the United States, homeopathic remedies are, like all health-care products, regulated by the Food and Drug Administration. However, the FDA treats homeopathic remedies very differently than conventional medicines. Homeopathic products do not need FDA approval before sale; they do have to be proven safe since the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, any products prior to 1994 may or may not have been tested for safety, but they do not have to prove efficacy; they do not have to be labeled with an expiration date; and they do not have to undergo finished product testing to verify contents and strength, all of these are voluntary actions done by the manufacturer. The manufacturer is required to have all ingredients on the label; however, it might not specify which ones are active. In the USA, only homeopathic medicines that claim to treat self-limiting conditions may be sold over the counter; homeopathic medicines that claim to treat a serious disease can be sold only by prescription. A memorandum, written in 1985 by attorneys for the American Association of Homeopathic Manufacturers, describes a meeting between the AAHP attorneys and high-ranking FDA officials to discuss whether homeopathic products must be proven effective to remain legally marketable. Such negotiations led to the issuance in 1988 (revised in 1995) of an FDA Compliance Policy Guide that permits homeopathic products "intended solely for self-limiting disease conditions amenable to self-diagnosis (of symptoms) and treatment" to be marketed as nonprescription drugs. In 2001, the FDA published a comprehensive review of mercury compounds in homeopathic drugs. This report indicated that nearly all examined compounds derived from the use of mercury. However, due to the extreme dilution of materials, the presence of mercury in the finished product would be minimal. At present the FDA Health Fraud Division only pursues claims which may cause direct harm to consumers through their use. Homeopathic drugs, largely regarded as equivalent to placebos, are not considered under these guidelines. Due to the significant dilution of the products, the agents become practically immeasurable: the harmful effects of homeopathic drugs is more likely to be that patients avoid conventional treatments.

In Asia, the use of homeopathic treatments is increasing, especially in India. Homeopathy arrived in India with Dr John Martin Honigberger in Lahore, in 1829–1830. India has the largest homeopathic infrastructure in the world, with low estimates at about 64,000, but going as high as 300,000 practicing homeopaths. In addition, there are 180 colleges teaching courses, and 7500 government clinics and 307 hospitals which dispense homeopathic remedies. In Malaysia, homeopathy was introduced during World War II and was brought by Indians via the British army. There is no legislation governing homeopathy in Malaysia and only a few medical doctors are involved in homeopathic treatments. In South Africa, homeopathy is regulated by the Associated Health Service Professions Act of 1982, which was set up to provide a registration and licensing framework for health professions. During the 1960s, all homeopathic colleges were closed by the South African Medical Council. However, conventional medical doctors retained the right to use homeopathic treatments.

References

- ^ "History of Homeopathy". Creighton University Department of Pharmacology. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ Tindle HA, Davis RB, Phillips RS, Eisenberg DM (2005). "Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US adults: 1997-2002". Alternative therapies in health and medicine. 11 (1): 42–9. PMID 15712765.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Thomas K, Coleman P (2004). "Use of complementary or alternative medicine in a general population in Great Britain. Results from the National Omnibus survey". Journal of public health (Oxford, England). 26 (2): 152–7. PMID 15284318.

- Singh P, Yadav RJ, Pandey A (2005). "Utilization of indigenous systems of medicine & homoeopathy in India". Indian J. Med. Res. 122 (2): 137–42. PMID 16177471.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Dynamization and Dilution". Creighton University Department of Pharmacology. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- "Similia similibus curentur (Like cures like)". Creighton University Department of Pharmacology. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- Organon of Medicine, Samuel Hahnemann, combined 5th/6th edition

- ^ Brien S, Lewith G, Bryant T (2003). "Ultramolecular homeopathy has no observable clinical effects. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled proving trial of Belladonna 30C". British journal of clinical pharmacology. 56 (5): 562–568. PMID 14651731.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McCarney RW, Linde K, Lasserson TJ (2004). "Homeopathy for chronic asthma". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD000353. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000353.pub2. PMID 14973954.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McCarney R, Warner J, Fisher P, Van Haselen R (2003). "Homeopathy for dementia". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD003803. PMID 12535487.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); "Homeopathy results". National Health Service. Retrieved 2007-07-25. - "Report 12 of the Council on Scientific Affairs (A–97)". American Medical Association. Retrieved 2007-07-25.; Linde K, Jonas WB, Melchart D, Willich S (2001). "The methodological quality of randomized controlled trials of homeopathy, herbal medicines and acupuncture". International journal of epidemiology. 30 (3): 526–531. PMID 11416076.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Altunç U, Pittler MH, Ernst E (2007). "Homeopathy for childhood and adolescence ailments: systematic review of randomized clinical trials". Mayo Clin Proc. 82 (1): 69–75. PMID 17285788.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ernst E, Pittler MH (1998). "Efficacy of homeopathic arnica: a systematic review of placebo-controlled clinical trials". Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 133 (11): 1187–90. PMID 9820349.

- ^ Linde K, Jonas WB, Melchart D, Willich S (2001). "The methodological quality of randomized controlled trials of homeopathy, herbal medicines and acupuncture". International journal of epidemiology. 30 (3): 526–531. PMID 11416076.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Linde K, Clausius N, Ramirez G; et al. (1997). "Are the clinical effects of homeopathy placebo effects? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials". Lancet. 350 (9081): 834–43. PMID 9310601.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ernst E (2001). "Rise in popularity of complementary and alternative medicine: reasons and consequences for vaccination". Vaccine. 20 Suppl 1: S90–3, discussion S89. PMID 11587822.

- ^ Ernst E (1997). "The attitude against immunisation within some branches of complementary medicine". Eur. J. Pediatr. 156 (7): 513–515. PMID 9243229.

- ^ Ernst E, White AR (1995). "Homoeopathy and immunization". The British journal of general practice: the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 45 (400): 629–630. PMID 8554846.

- ^ Jha, Alok (2006-07-14). "Homeopaths 'endangering lives' by offering malaria remedies". Retrieved 2007-07-25.

{{cite news}}: Text "work Guardian Unlimited" ignored (help) - ^ Delaunay P, Cua E, Lucas P, Marty P (2000). "Homoeopathy may not be effective in preventing malaria". BMJ. 321 (7271): 1288. PMID 11082104.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jones, Meirion (2006-07-14). "Malaria advice 'risks lives'". BBC News. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- "The Chemical Philosophy". U.S. National Library of Medicine. National Institutes of Health. 1998-04-27. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- "About Homoeopathy". ccrhindia.org. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- Federspil, Giovanni. "Letters, A critical overview of homeopathy" (PDF). Annals. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - * Template:Harvard reference page 18

- Griffin, J. P., Venetian treacle and the foundation of medicines regulation (PDF), British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 58:3, Page 317. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02147.x

- ^ Kaufman, Martin (1971-10-01). Homeopathy in America: The Rise and Fall of a Medical Heresy. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801812385.

- Wright, Iaian. "Shakespeare and Queens' (Part II)". Queens' College Cambridge. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ Lasagna, Louis. The doctors' dilemmas. Collier Books. p. 33.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Nicholls, Philip A. (March 1988). Homeopathy and the Medical Profession. Croom Helm Ltd. ISBN 978-0709918363.

- ^ Hahnemann, Dr Samuel (1818). Organon of medicine. Leipzig.

- Hahnemann, Samuel (1831). "Appeal to Thinking Philanthropist Respecting the Mode of Propagation of the Asiatic Choler". Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- Baxter AG (2001). "Louis Pasteur's beer of revenge". Nat. Rev. Immunol. 1 (3): 229–32. PMID 11905832.

- Coley NG (2004). "Medical chemists and the origins of clinical chemistry in Britain (circa [[1750]]–[[1850]])". Clin. Chem. 50 (5): 961–72. PMID 15105362.

{{cite journal}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - Ramberg PJ (2000). "The death of vitalism and the birth of organic chemistry: Wohler's urea synthesis and the disciplinary identity of organic chemistry". Ambix. 47 (3): 170–95. PMID 11640223.

- http://homeoint.org/books4/bradford/chapter35.htm Thomas L Bradford, The Life and Letters of Hahnemann, Ch.35

- Emmans Dean, Michael (2001). "Homeopathy and "the progress of science"" (PDF). History of science; an annual review of literature, research and teaching. 39 (125 Pt 3): 255–83. PMID 11712570. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- ^ "Homeopathic Provings". Creighton University School of Medicine. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- Kirschmann, Anne Taylor (December 2003). A Vital Force: Women in American Homeopathy. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0813533209.

- "Homeopathic Dynamization and Dilution". Creighton University School of Medicine. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- Winston, Julian (2006). "Homeopathy Timeline". "The Faces of Homoeopathy". Whole Health Now. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- Ernst E, Kaptchuk TJ (1996). "Homeopathy revisited". Arch. Intern. Med. 156 (19): 2162–4. PMID 8885813.

- Sir John Forbes, Homeopathy, Allopathy and Young Physic, London, 1846

- James Y Simpson, Homoeopathy, Its Tenets and Tendencies, Theoretical, Theological and Therapeutical, Edinburgh: Sutherland & Knox, 1853, 11

- Holmes, Oliver Wendell (1842). Homœopathy, and its Kindred Delusions; two lectures delivered before the Boston society for the diffusion of useful knowledge. Boston, MA: William D. Ticknor. OCLC 166600876. Found online at,Holmes, Oliver Wendell. "Homeopathy and Its Kindred Delusions". Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- Winston, Julian. "OUTLINE OF THE ORGANON". Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- Hahnemann, Samuel. "Organon Of Medicine". Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- David Little. "The Classical View on Miasms". Homeopathy Online. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - The Chronic Diseases, their Nature and Homoeopathic Treatment, Dresden and Leipsic, Arnold. Vols. 1, 2, 3, 1828; vol. 4, 1830

- Samuel Hahnemann. "Organon, 5th edition, para 29". Homeopathy Home.com. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ^ "Miasms in homeopathy". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Dr J W Ward. "Taking the History of the Case". Pacific Coast Jnl of Homeopathy, July 1937. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- "Cause of Disease in homeopathy". Creighton University Department of Pharmacology. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- Birnbaum NR, Goldschmidt RH, Buffett WO (1999). "Resolving the common clinical dilemmas of syphilis". American family physician. 59 (8): 2233–40, 2245–6. PMID 10221308.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Critical review of The Science of Homeopathy from the British Homoeopathic Journal Volume 67, Number 4, October 1978

- "Online Museum". The Institute for the History of Medicine. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ^ "Dynamization and Dilution". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Resch, G, (1987). Scientific Foundations of Homoeopathy. Barthel & Barthel Publishing.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Robert, Ellis Dudgeon (1853). Lectures on the Theory & Practice of Homeopathy (PDF). London. pp. 526–7. ISBN 81-7021-311-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Little, David. "Hahnemann's Advanced Methods". Simillimum.com. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- Edwin Wheeler, Charles (1941). Dr. Hughes: Recollections of Some Masters of Homeopathy. Health Through Homeopathy.

- Bodman, Frank (1970). he Richard Hughes Memorial Lecture. BHJ. pp. 179–193.

- Cuesta Laso LR, Alfonso Galán MT (2007). "Possible dangers for patients using homeopathy: may a homeopathic medicinal product contain active substances that are not homeopathic dilutions?". Medicine and law. 26 (2): 375–86. PMID 17639858.

- Dantas F, Fisher P, Walach H; et al. (2007). "A systematic review of the quality of homeopathic pathogenetic trials published from 1945 to 1995". Homeopathy : the journal of the Faculty of Homeopathy. 96 (1): 4–16. PMID 17227742.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cassedy, James H. (June 1999). American Medicine and Statistical Thinking, 1800–1860. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1583484289.

- Fye WB (1986). "Nitroglycerin: a homeopathic remedy" (PDF). Circulation. 73 (1): 21–9. PMID 2866851.

- "Fragmenta de Viribus Medicamentorum Positivis Sive in sano Corpore Humano Observatis". Retrieved 2007-10-16.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - Hahnemann, Samuel. "Materia Medica Pura". hpathy.com. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- von Bönninghausen, Clemens (1999, Reprint Ed.). Boenninghausen's Characteristics and Repertory with Word Index. New Delhi : B. Jain. ISBN 8-170-21207-3.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Bellavite P, Conforti A, Piasere V, Ortolani R (2005). "Immunology and homeopathy. 1. Historical background". Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM. 2 (4): 441–52. PMID 16322800.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Stehlin, Isadora (1996-12-XX). "Homeopathy: Real Medicine or Empty Promises?". Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Jonas WB, Kaptchuk TJ, Linde K (2003). "A critical overview of homeopathy". Ann. Intern. Med. 138 (5): 393–399. PMID 12614092.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jones, Kathryn. "Materia Medica: Remedy Information". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Bellavite P, Conforti A, Piasere V, Ortolani R (2005). "Immunology and homeopathy. 1. Historical background". Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine: eCAM. 2 (4): 441–452. doi:10.1093/ecam/neh141. PMID 16322800.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Norland, Misha (1998). "The Homœopathic Proving of Positronium". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- CLARKE, John Henry. "MATERIA MEDICA". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- English, Mary. "The Homeopathic proving of 'Tempesta' the Storm". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Doheny, Kathleen. "Homeopathy: Natural Approach or All a Fake?". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Shah, Rajesh. "Call for Introspection and Awakening" (PDF). Life Force Center. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Barwell, Bruce. "Homoeopathica: The Wo-wo Effect". New Zealand Homoeopathic Society. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- "Isopathy". Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- Tautopathy – An Introduction, Manish Bhatia, Tautopathy, Homeopathy for Everyone: Everything Homeopathic!

- van Haselen RA (1999). "The relationship between homeopathy and the Dr Bach system of flower remedies: a critical appraisal". The British homoeopathic journal. 88 (3): 121–7. PMID 10449052.

- Ernst E (2002). ""Flower remedies": a systematic review of the clinical evidence". Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 114 (23–24): 963–6. PMID 12635462.

- Saxton, J. (2007). "The diversity of veterinary homeopathy". Homeopathy. 96 (1): 3. doi:10.1016/j.

- Tiekert, Dr. Carvel G. "What is Holistic medicine?". American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ Hektoen L (2005). "Review of the current involvement of homeopathy in veterinary practice and research". Vet. Rec. 157 (8): 224–9. PMID 16113167.

- ^ Teixeira J (2007). "Can water possibly have a memory? A sceptical view". Homeopathy : the journal of the Faculty of Homeopathy. 96 (3): 158–162. doi:10.1016/j.homp.2007.05.001.

- ^ Milgrom LR (2007). "Conspicuous by its absence: the Memory of Water, macro-entanglement, and the possibility of homeopathy". Homeopathy : the journal of the Faculty of Homeopathy. 96 (3): 209–19. doi:10.1016/j.homp.2007.05.002. PMID 17678819.

- ^ Levy G (1986). "Kinetics of drug action: an overview". J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 78 (4 Pt 2): 754–61. PMID 3534056.

- ^ Barrett, Stephen (2004-12-28). "Homeopathy: The Ultimate Fake". National Institutes of Health. NCCAM. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- Ernst E (2007). "Placebo: new insights into an old enigma". Drug Discov. Today. 12 (9–10): 413–8. PMID 17467578.

- Teixeira1 J, Luzar A, Longeville S. (2006). "Dynamics of hydrogen bonds: how to probe their role in the unusual properties of liquid water". J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 18: S2353–S2362. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/18/36/S09.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Weissmann G (2006). "Homeopathy: Holmes, Hogwarts, and the Prince of Wales". FASEB J. 20 (11): 1755–8. PMID 16940145.

- "Horizon's Homeopathic Coup, Cuzco's Altitude, More Funny Sites, The Clangers, Overdue, Orbito Nabbed in Padua, Randi A Zombie?, Stellar Guests at Amazing Meeting, and Great New Shermer Books!". Swift, Online Newsletter of the JREF, November 29, 2002, James Randi Educational Foundation. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- Boyd WA, Williams PL (2003). "Comparison of the sensitivity of three nematode species to copper and their utility in aquatic and soil toxicity tests". Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 22 (11): 2768–74. PMID 14587920.

- Goldoni M, Vettori MV, Alinovi R, Caglieri A, Ceccatelli S, Mutti A (2003). "Models of neurotoxicity: extrapolation of benchmark doses in vitro". Risk Anal. 23 (3): 505–14. PMID 12836843.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Yu HS, Liao WT, Chai CY (2006). "Arsenic carcinogenesis in the skin". J. Biomed. Sci. 13 (5): 657–66. doi:10.1007/s11373-006-9092-8. PMID 16807664.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ernst E (2005). "Is homeopathy a clinically valuable approach?". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26 (11): 547–8. PMID 16165225.

- Gray, Bill (2000-05-26). Homeopathy: Science or Myth?. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1556433320.

- "Questions and Answers About Homeopathy". National Institutes of Health. NCCAM. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ^ Kleijnen J, Knipschild P, ter Riet G (1991). "Clinical trials of homoeopathy". BMJ. 302 (6772): 316–323. PMID 1825800.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Milazzo S, Russell N, Ernst E (2006). "Efficacy of homeopathic therapy in cancer treatment". Eur. J. Cancer. 42 (3): 282–289. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2005.09.025. PMID 16376071.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kolisko, Lily, Physiologisher und physikalischer Nachweis der Wirksamkeit kleinster Entitäten, Stuttgart (1959), Junker, H. Biologisches Zentralblatt, 45. Nr. 1 (1925), p. 26 and Plügers Arhiv f. ges. Phys. 219B Nr. 5/6 (1928)

- Wälchli C, Baumgartner S, Bastide M (2006). "Effect of low doses and high homeopathic potencies in normal and cancerous human lymphocytes: an in vitro isopathic study". Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.). 12 (5): 421–427. doi:10.1089/acm.2006.12.421. PMID 16813505.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Walach H, Köster H, Hennig T, Haag G (2001). "The effects of homeopathic belladonna 30CH in healthy volunteers -- a randomized, double-blind experiment". Journal of psychosomatic research. 50 (3): 155–160. PMID 11316508.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hirst SJ, Hayes NA, Burridge J, Pearce FL, Foreman JC (1993). "Human basophil degranulation is not triggered by very dilute antiserum against human IgE". Nature. 366 (6455): 525–527. doi:10.1038/366525a0. PMID 8255290.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ovelgönne JH, Bol AW, Hop WC, van Wijk R (1992). "Mechanical agitation of very dilute antiserum against IgE has no effect on basophil staining properties". Experientia. 48 (5): 504–508. PMID 1376282.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Witt CM, Bluth M, Hinderlich S; et al. (2006). "Does potentized HgCl2 (Mercurius corrosivus) affect the activity of diastase and alpha-amylase?". Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.). 12 (4): 359–365. doi:10.1089/acm.2006.12.359. PMID 16722785.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Guggisberg AG, Baumgartner SM, Tschopp CM, Heusser P (2005). "Replication study concerning the effects of homeopathic dilutions of histamine on human basophil degranulation in vitro". Complementary therapies in medicine. 13 (2): 91–100. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2005.04.003. PMID 16036166.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Declaration of Helsinki should be strengthened" BMJ 2000;321:442–445 (12 August)

- Long L, Ernst E (2001). "Homeopathic remedies for the treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic review". The British homoeopathic journal. 90 (1): 37–43. PMID 11212088.

- Whitmarsh TE, Coleston-Shields DM, Steiner TJ (1997). "Double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study of homoeopathic prophylaxis of migraine". Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache. 17 (5): 600–604. PMID 9251877.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Maddox, John (28 July 1988). "'High-dilution' experiments a delusion" (PDF). Nature. 334: 287–290.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sullivan, Walter (1988-07-27). "Water That Has a Memory? Skeptics Win Second Round". The New York Times. nytimes.com. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Dr. Beneveniste defended his results however, comparing the inquiry to the Salem witch hunts and asserting that "It may be that all of us are wrong in good faith. This is no crime but science as usual and only the future knows."

- "Homeopathy results". National Health Service. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- "Report 12 of the Council on Scientific Affairs (A–97)". American Medical Association. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- Weissmann, Gerald (2006). "Homeopathy: Holmes, Hogwarts, and the Prince of Wales". The FASEB Journal. 20: 1755–1758. PMID 16940145. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "Zicam Marketers Sued". Homeowatch.org. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- "Zicam Settlement". Online Lawyer Source. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- Boodman, Sandra (January 31, 2006). "Paying through the Nose". Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- Pray, W.S. (1992). "A challenge to the credibility of homeopathy". Am. J. Pain Mangmnt., (2): 63–71.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - English, John (October 1992). "The issue of immunization". British Homoeopathic journal. 81 (4): 161–163. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

{{cite journal}}: Text "10.1016/S0007-0785(05)80171-1" ignored (help); Text "doi" ignored (help) - Bunyan, Nigel (22/03/2007). "Patient died after being told to stop heart medicine". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Fitness to PractiSe Panel hearing on Dr Marisa Viegas". General Medical Council. June 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- Critical review of The Science of Homeopathy from the British Homoeopathic Journal Volume 67, Number 4, October 1978

- Birnbaum NR, Goldschmidt RH, Buffett WO (1999). "Resolving the common clinical dilemmas of syphilis". American family physician. 59 (8): 2233–40, 2245–6. PMID 10221308.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pray WS (2006). "Ethical, scientific, and educational concerns with unproven medications". American journal of pharmaceutical education. 70 (6): 141. PMID 17332867.

- Ernst, E (2004). "Ethical problems arising in evidence based complementary and alternative medicine". J Med Ethics. 30 (2): 156–159. PMID 15082809.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Legal Status of Traditional Medicine and Complementary/Alternative Medicine: A Worldwide Review" (PDF). World Health Organization. World Health Organization. 2001. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- Bundesratsentscheid über die Leistungen für Alternativmedizin: Information about Homeopathy in Switzerland by Vera Kaufmann, BHSc.Hom. (in German)

- Leary, B, Lorentzon M & Bosanquet, A, 1998, It Wont Do Any Harm: Practice & People At The London Homeopathic Hospital, 1889–1923, in Juette, Risse & Woodward, 1998 Juette, R, G Risse & J Woodward , 1998, Culture, Knowledge And Healing: Historical Perspectives On Homeopathy In Europe And North America, Sheffield Univ. Press, UK, p.253

- Leary, et al, 1998, 254

- Sharma, Ursula, 1992, Complementary Medicine Today, Practitioners And Patients, Routledge, UK, p.185

- "PHOTOTHÈQUE HOMÉOPATHIQUE". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- "The Royal Archives are based in the Round Tower at Windsor Castle". British Homeopathic Association. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Ross S, Simpson CR, McLay JS (2006). "Homoeopathic and herbal prescribing in general practice in Scotland". British journal of clinical pharmacology. 62 (6): 647–652, discussion 645–646. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02702.x. PMID 16796701.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - MacLennan AH, Wilson DH, Taylor AW (1996). "Prevalence and cost of alternative medicine in Australia". Lancet. 347 (9001): 569–573. PMID 8596318.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Spigelblatt L, Laîné-Ammara G, Pless IB, Guyver A (1994). "The use of alternative medicine by children". Pediatrics. 94 (6 Pt 1): 811–4. PMID 7970994.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nigenda G, Cifuentes E, Hill W (2004). "Knowledge and practice of traditional medicine in Mexico: a survey of healthcare practitioners". International journal of occupational and environmental health: official journal of the International Commission on Occupational Health. 10 (4): 416–420. PMID 15702756.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Questions and Answers About Homeopathy NCCAM, National Institutes of Health

- Frederick Karst, Homeopathy In Illinois, Caduceus, 4:2, 1988, pp.1-33; p.5

- Charles S Cameron, Homeopathy in Retrospect, Trans. Stud. Coll. Phys. Philadelp., 27, 1959, 28-33; p.30

- Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL; et al. (1998). "Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey". JAMA. 280 (18): 1569–1575. PMID 9820257.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sec. 400.400 Conditions Under Which Homeopathic Drugs May be Marketed (CPG 7132.15) Downloaded 26 April 2007.

- Meeting between FDA Officials and Homeopathic Pharmacists (1985). Memorandum, February 12, 1985

- Compliance Policy Guide (CPG 7132.15). Conditions Under Which Homeopathic Drugs May be Marketed. Revised March 1995

- Report on Mercury Compounds in DrugsMERCURY COMPOUNDS IN DRUGS AND FOOD FDA/Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Last Updated: August 09, 2001

- Internet Health and Fraud Site, US Food and Drug AdministrationUS FDA Internet Site, 2007

- Bhatia, Manish. "Homeopathy in India". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Kishore J (1973). "About entry of homoeopathy into India". Bulletin of the Institute of Medicine (Hyderabad). 3: 76–78. PMID 11609675.

- Dr. Raj Kumar Manchanda & Dr. Mukul Kulashreshtha, Cost Effectiveness and Efficacy of Homeopathy in Primary Health Care Units of Government of Delhi- A study

- Arokiasamy, P. "World Health Survey, 2003" (PDF). International Institute for Population Sciences. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Homeopathy in Malaysia". Whole Health Now Homeopathy. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

External links

- Homeopathy: Real Medicine or Empty Promises? – Food and Drug Administration report

- Wilhelm Ameke, History of Homœopathy, with an appendix on the present state of University medicine, translated by A. E. Drysdale, edited by R. E. Dudgeon, London: E. Gould & Son, 1885

| Topics in homeopathy | |

|---|---|

| Workbooks | |

| Historical documents | |

| Homeopaths |

|

| Organizations | |

| Related | |

| Criticism | |

| See also | |