This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 76.178.249.48 (talk) at 21:56, 30 January 2008 (→See also). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:56, 30 January 2008 by 76.178.249.48 (talk) (→See also)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)In most Indian philosophical traditions, including the Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh and Jain systems, an ongoing cycle of birth, death, and rebirth is assumed as a fact of nature. These systems differ widely, however, in the terminology with which they describe the process and in the metaphysics they use in interpreting it. In Hinduism, it is avidya, or ignorance, of one's true self, that leads to ego-consciousness of the body and the phenomenal world. This grounds one in desire and the perpetual chain of karma and reincarnation.

In India the concept of reincarnation is first recorded in the Upanishads (c. 800 BCE), which are philosophical and religious texts composed in Sanskrit. The notion of reincarnation is most notably present in the Śvetāśvatara Upanishad 5.11 and Kauśītāki Upanishad 1.2. In other Upanishads, reincarnation as a theory it is not specifically mentioned. The doctrine of reincarnation is also absent in the Vedas, which are generally considered the oldest of the Hindu scriptures.

According to Hinduism, the soul (atman) is immortal, while the body is subject to birth and death. The Bhagavad Gita states that:

Worn-out garments are shed by the body;

Worn-out bodies are shed by the dweller within the body. New bodies are donned by the dweller, like garments.

The idea that the soul (of any living being - including animals, humans and plants) reincarnates is intricately linked to karma, another concept first introduced in the Upanishads. Karma (literally: action) is the sum of one's actions, and the force that determines one's next reincarnation. The cycle of death and rebirth, governed by karma, is referred to as samsara.

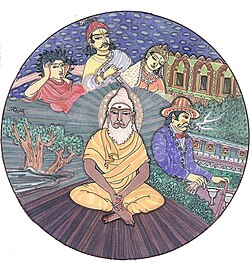

Hinduism teaches that the soul goes on repeatedly being born and dying. One is reborn on account of desire: a person desires to be born because he or she wants to enjoy worldly pleasures, which can be enjoyed only through a body. Hinduism does not teach that all worldly pleasures are sinful, but it teaches that they can never bring deep, lasting happiness or peace (ānanda). According to the Hindu sage Adi Shankaracharya - the world as we ordinarily understand it - is like a dream: fleeting and illusory. To be trapped in Samsara is a result of ignorance of the true nature of being.

After many births, every person eventually becomes dissatisfied with the limited happiness that worldly pleasures can bring. At this point, a person begins to seek higher forms of happiness, which can be attained only through spiritual experience. When, after much spiritual practice (sādhanā), a person finally realizes his or her own divine nature—ie., realizes that the true "self" is the immortal soul rather than the body or the ego—all desires for the pleasures of the world will vanish, since they will seem insipid compared to spiritual ānanda. When all desire has vanished, the person will not be reborn anymore.

When the cycle of rebirth thus comes to an end, a person is said to have attained moksha, or salvation. While all schools of thought agree that moksha implies the cessation of worldly desires and freedom from the cycle of birth and death, the exact definition of salvation depends on individual beliefs. For example, followers of the Advaita Vedanta school (often associated with jnana yoga) believe that they will spend eternity absorbed in the perfect peace and happiness that comes with the realization that all existence is One (Brahman), and that the immortal soul is part of that existence. Thus they will no longer identify themselves as individual persons, but will see the "self" as a part of the infinite ocean of divinity, described as sat-chit-ananda (existence-knowledge-bliss). The followers of full or partial Dvaita schools ("dualistic" schools, such as bhakti yoga), on the other hand, perform their worship with the goal of spending eternity in a loka, (spiritual world or heaven), in the blessed company of the Supreme being (i.e Krishna or Vishnu for the Vaishnavas, Shiva for the Shaivites). The two schools (Dvaita & Advaita) are not necessarily contradictory, however. A follower of one school may believe that both types of salvation are possible, but will simply have a personal preference to experience one or the other. Thus, it is said, the followers of Dvaita wish to "taste sugar," while the followers of Advaita wish to "become sugar."

Footnotes

- Bhagavad Gita II.22, ISBN 1-56619-670-1

- See Bhagavad Gita XVI.8-20

- Rinehart, Robin, ed., Contemporary Hinduism19-21 (2004) ISBN 1-57607-905-8

- Karel Werner, A Popular Dictionary of Hinduism 110 (Curzon Press 1994) ISBN 0-7007-0279-2

- Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, Translation by Swami Nikhilananda (8th Ed. 1992) ISBN 0-911206-01-9