This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 155.84.57.253 (talk) at 19:34, 19 July 2005 (→Vampires in literature, art, and pop culture). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:34, 19 July 2005 by 155.84.57.253 (talk) (→Vampires in literature, art, and pop culture)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Vampire (disambiguation).| It has been suggested that History of vampire lore be merged into this article. (Discuss) |

A vampire is a mythical or folkloric different type of species (Nosferatu vampiro) much like humans (Homo sapien) said to subsist on human and/or animal blood (hematophagy), often having unnatural powers, heightened bodily functions and the ability to transform. Usually the vampire is made into itself by the transplanting of vampire blood into the vital systems. Some cultures have myths of non-human vampires, such as demons or animals like bats, dogs, and spiders. Vampires are often described as having a wide variety of additional powers and character traits, extremely variable in different traditions, and are a frequent subject of folklore, cinema, and contemporary fiction.

Vampirism is the practice of drinking blood. In folklore and popular culture the term generally refers to a belief that one can gain supernatural powers by drinking human blood. The historical practice of vampirism can generally be considered a more specific and less commonly occurring form of cannibalism. The consumption of another's blood has been used as a tactic of psychological warfare intended to terrorize the enemy, and it can be used to reflect various spiritual beliefs.

In zoology the term vampirism is used to refer to leeches, mosquitos, mistletoe, vampire bats, and other organisms that prey upon the bodily fluids of other creatures. This term also applies to mythic animals of the same nature, including the chupacabra.

Vampires in history and culture

Tales of the dead craving blood are ancient. In Homer's Odyssey, for example, the shades that Odysseus meets on his journey to the underworld are lured to the blood of freshly sacrificed rams, a fact which Odysseus uses to his advantage to summon the shade of Tiresias. Roman fables describe the strix, a nocturnal bird that fed on human flesh and blood. The Roman strix is the source of the Romanian vampire, the Strigoi, which was also influenced by the Slavic vampire, and the Albanian Shtriga.

In early Slavic folklore, a vampire drank blood, was afraid of (but could not be killed by) silver, and could be destroyed by cutting off its head and putting it between the corpse's legs, or by putting a wooden stake into its heart.

Medieval historians and chroniclers Walter Map and William of Newburgh recorded the earliest English stories of vampires in the 12th century.

In popular western culture, vampires are depicted as unaging, intelligent, and mystically endowed in many ways. The vampire typically has a variety of notable abilities. These include great strength and immunity to any lasting effect of any injury by mundane means, with specific exceptions. Vampires, though presumed to, do not and cannot evolve into any other shape or form than that of their vampirish body. Yet another myth tells that vampires have extended canines, like fangs, but they do not. Their teeth and nails are twenty times harder than a humans, so they use their fingernails to cut open a vein briefly to take what they need from their human victim. No vampire is thick enough to use their teeth, for it makes a noticable mess and the marks are easier to identify, resembling teeth.

It is believed that vampires have no reflection, as traditionally it was thought that mirrors reflected your soul and creatures of evil have no soul. Fiction has extended this belief to an actual aversion to mirrors, as depicted in Bram Stoker's novel Dracula when the vampire casts Harker's shaving mirror out of the window.

Strengths and weaknesses

The abilities and limitations of vampires vary significantly from early folklore to modern Hollywood. However, Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) is principally the foundation for the modern vampire. In his novel, Stoker outlines some general strengths and weaknesses of vampires.

Abilities

- Vampires are immortal. "The vampire live on, and cannot die by mere passing of the time... When they become such, there comes with the change the curse of immortality. They cannot die, but must go on age after age adding new victims and multiplying the evils of the world."

- Vampires are twenty times stronger than men, "the UnDead are strong. He have always the strength in his hand of twenty men."

- Vampires are shape-shifters, "he can grow and become small, and he can at times vanish and come unknown... Even more, we have seen amongst us that he can even grow younger... He can transform himself to wolf... he can be as bat... He come on moonlight rays as elemental dust."

- Vampires can to a degree control the weather and the elements, "he can, within his range, direct the elements, the storm, the fog, the thunder... He can come in mist which he create."

- Vampires can fly because of their shapeshifting abilities (e.g., bats, owls) and their control of wind (e.g., fog, mist, dust, straw).

- Vampires have the hypnotic power of influence and suggestion, "he can command all the meaner things, the rat, and the owl, and the bat, the moth, and the fox, and the wolf."

- Vampires can see in the dark, "no small power this, in a world which is one half shut from the light."

- Vampires cast no shadow and have no reflection. "He throws no shadow, he make in the mirror no reflect."

- Vampires can enter and exit anything, "slip through a hairbreadth space at the tomb door... He can, when once he find his way, come out from anything or into anything, no matter how close it be bound or even fused up with fire, solder you call it."

- Vampires are skilled in necromancy, the conjuration of the spirits of the dead. "All the dead that he can come nigh to are for him at command."

- Vampires are very fierce and savage like animals, without heart or conscience, with no emotion or sympathy. "He is brute, and more than brute, he is devil in callous, and the heart of him is not."

- Vampires are very intelligent and are more cunning than man, "he is of cunning more than mortal, for his cunning be the growth of ages."

- Vampires become more powerful each time they feed. "The nosferatu do not die like the bee when he sting once. He is only stronger, and being stronger, have yet more power to work evil." Subsequently, the older the vampire the more powerful it usually is. The above abilities can increase with age or decrease with youth. "Therefore I shall fix some things she like not... She is young as UnDead, and will heed."

Limitations

- Vampires are powerless during the day. "His power ceases, as does that of all evil things, at the coming of the day...We have on our side power...a power denied to the vampire kind...the hours of the day and the night are ours equally."

- Vampires may not trespass without permission. "He may not enter anywhere at the first, unless there be some one of the household who bid him to come, though afterwards he can come as he please."

- There are things in which vampires have no power against such as garlic, a branch of wild rose, and all things sacred (e.g., holy water, a crucifix, a rosary, or sacred objects from other faiths). "I had laid over the clamps of those doors garlic, which the UnDead cannot bear, and other things which they shun....I shall fix some things she like not, garlic and a crucifix, and so seal up the door of the tomb...The branch of wild rose on his coffin keep him that he move not from it."

- In Bram Stoker's Dracula (1892), there are three referenced ways to permanently kill a vampire: a sacred bullet, a stake through the heart, or decapitation. "A sacred bullet fired into the coffin kill him so that he be true dead, and as for the stake through him, we know already of its peace, or the cut off head that giveth rest." Note, this includes other means of death that effectively removes a vampire's head, successfully killing the vampire (e.g., cremation, nuclear weapons).

- Additionally, in the novel Dracula, there are two implied ways to kill a vampire: starvation, or normal death during daytime. Vampires must feed on blood to survive or they will starve to death. "He can flourish when that he can fatten on the blood of the living...he cannot flourish without this diet, he eat not as others." However, the novel does not rule out the possibility of reanimation if the vampire corpse is feed (as occasionally depicted in films; e.g., Underworld (2003)). A vampire can be killed like a normal man, during the day, when his powers are limited to the powers of mortal men. "Today this Vampire is limit to the powers of man, and till sunset he may not change." However, the novel does not rule out the possibility of reanimation once the sun sets.

Types of beliefs in vampires

It seems that until the 19th century, vampires in Europe were thought to be hideous monsters rather than the debonair vampire made popular by later fictional treatments. They were usually believed to rise from the bodies of suicide victims, criminals, or evil magicians, though in some cases an initial vampire thus "born of sin" could pass on his vampirism onto his innocent victims. In other cases, however, a victim of an untimely or cruel death was susceptible of becoming a vampire.

In Moravia, vampires were fond of throwing off their shrouds and attacking their victims in the nude.

In Albania, a type of vampire known as the Liogat was suppossed to be the reanimated corpse of Albanians of Turkish descent. It was covered in a shroud and wore high heeled shoes. The only way to vanquish it was to have a wolf bite its legs off so it would never rise again from its grave.

In Bulgaria, a vampire had only one nostril and slept with his left eye open and his thumbs linked. It was held responsible for cattle plagues.

In Aztec mythology, the Civatateo was a sort of vampire, created when a noblewoman died in childbirth.

In Australian aboriginal mythology, the "Yara-Ma-Yha-Who" was a vampire with suckers on his fingers that lurked in fig trees.

In Malaysian folklore, the Penanggalan was a vampire whose head could separate from its body, with its entrails dangling from the base of its neck. The Pontianak was a female vampire that sucked the blood of newborn babies and sometimes that of young children or pregnant women.

In Philippine folklore, the Manananggal was a female vampire whose entire upper body could separate from her lower body and who could fly using wings. She sucked the blood of fetuses. The Aswang was believed to always be a female of considerable beauty by day and, by night, a fearsome flying fiend. She lived in a house, could marry and have children, and was a seemingly normal human during the daylight hours.

Gypsy tradition in the Balkans is said to have held that melons and pumpkins may become vampires; see the article on vampire watermelons.

In the Caribbean, vampires known as Soucoyant in Trinidad and Tobago, Ol' Higue in Jamaica, and Loogaroo in Grenada, take the form of old women during the day, and at night shed their skin to become flying balls of flame who seek blood. They were said to be notoriously obsessive compulsive, and could be thwarted by sprinkling salt or rice at entrances, crossroads and near beds. The vampire would feel compelled to pick up every grain. They could also be killed by rubbing salt into their discarded skin, which would burn them upon returning to it before morning.

In India (especially in the southern state of Kerala) vampires (known as Yakshis) were beautiful women who seduced men in order to kill or eat them. They are said to be averse to iron objects in addition to other religious symbols, and could be killed by driving an iron nail through the head. They could also be imprisoned in trees using blessed objects. India is also home to the vetala, a wraithly vampire that can leave its host body to feed.

In the modern folklore of Latin America, the chupacabra is a vampiric creature that feeds upon domesticated animals.

Other vampire types:

- Brazilian vampires had plush-covered feet.

- Chinese vampires are also known as Hopping corpses.

- Mexican vampires were easily recognizable by their fleshless skulls.

- The Rocky Mountain vampires sucked the blood out of its victim's ears using its pointed nose.

Lilith

Vampire-like spirits called the Lilu are mentioned in early Babylonian demonology. These female demons roam during the hours of darkness, hunting and killing newborn babies and pregnant women. One of these demons, named Lilitu, was later adapted into Jewish demonology as Lilith. Lilitu/Lilith is sometimes attributed as the mother of the vampires. For further information, see the article on Lilith.

Contemporary belief in vampires

Belief in vampires still persists across the globe. During January of 2003, mobs in Malawi stoned to death one individual and attacked four others, including Governor Eric Chiwaya, due to a belief that the government is colluding with vampires.

In January 2005, it was reported that an attacker had bitten a number of people in Birmingham, England, fuelling concerns about a vampire roaming the streets. However, local police stated that no such crimes had been reported to them, and this case appears to be an urban legend.

Natural phenomena that propagate the vampire myth

Pathology and vampirism

Some people argue that vampire stories might have been influenced by a rare illness called porphyria. The disease disrupts the production of heme. People with extreme cases of this hereditary disease can be so sensitive to sunlight that they can get a sunburn through heavy cloud cover, causing them to be nocturnal and avoid all light. People with porphyria can also have red eyes and teeth, resulting from buildup of red heme intermediates (porphyrins). Certain forms of porphyria are also associated with neurological symptoms, which can create psychiatric disorders. However, the hypotheses that porphyria sufferers "crave" the heme in human blood, or that the consumption of blood might ease the symptoms of porphyria, are based in ignorance.

Others argue that there is a relationship between vampirism and rabies. The legend of vampirism is known to have existed in the 19th century Eastern Europe, where there were massive rabies outbreaks. Rabies causes high fever, loss of appetite, and fatigue as initial symptoms. In later stages, patients try to avoid the sunlight and prefer walking at night. Strong light and mirrors can cause episodes characterized by violent and animal-like behaviors and a tendency to attack people and bite them. Concomitant facial spasms might give the patient an animal-like (or a vampire-like) expression. In a furious form of the disease, patients might have an increased urgency for sexual activity or occasionally vomit blood. Rabies is contagious.

Fountain of blood when staked

As a body decomposes, the internal organs rot first because the food that is fermenting there continues fermenting and gases produced cannot get out. As a result, a body can swell like a balloon. Put pressure on this and the pressure seeks a way to escape.

Finding vampires in graves

When the coffin of an alleged vampire was opened, people sometimes found the cadaver in a "healthy state" and beautiful, meaning that the corpse was a well-fed vampire. Folkloric accounts almost universally represent the vampire as having ruddy or dark skin, not the pale skin of vampires in literature and film. Reasons for this appearance include:

- In the past, people were often malnourished and therefore thin in life. Corpses swell as gases from decomposition accumulate in the torso. The implication was that the corpse was not famished and, because blood was sometimes found in the corners of the mouth, it was assumed that the "vampire" had been drinking blood.

- Natural processes of decomposition, absent embalming, tend to darken the skin of a corpse — hence the black, blue, or red complexion of the folkloric vampire.

Drinking blood

There have been a number of murderers who performed this seemingly vampiric ritual upon their victims. Serial killers Peter Kurten and Richard Trenton Chase were both called "vampires" in the tabloids after they were discovered drinking the blood of the people they murdered, for example. Legends that Erzsébet Báthory, a medieval Hungarian aristocrat, murdered hundreds of women in bizarre rituals involving blood, helped mold contemporary vampire legends. Some psychologists in modern times recognize a disorder called clinical vampirism (or Renfield's syndrome, from Dracula's insect-eating henchman in the novel by Bram Stoker), where the victim is obsessed with drinking blood, either from animals or humans.

Also, the lust for blood (and sexual lusts) which is characteristic of vampires, especially Dracula, is known as "vivephila", or the paraphilia from a dead person towards a living person. It is the opposite of necrophilia.

Vampire bats

The three species of vampire bat are all endemic to Latin America, and there is no evidence to suggest that they had any Old World relatives within human memory. It is therefore unlikely that the folkloric vampire represents a distorted presentation or memory of the bat. The bats were named after the folkloric vampire rather than vice versa; the Oxford English Dictionary records the folkloric use in English from 1734 and the zoological not until 1774. However, once the vampire bats became known in western culture, their existence certainly reinforced and shaped the vampire legend, and it is common for vampires to be represented as bat-like in one way or another and have the ability to transform into one when desired which in turns grants the ability to fly.

Vampires in literature, art, and pop culture

Lord Byron introduced many common elements of the vampire theme to Western literature in his epic poem The Giaour (1813). These include the combination of horror and lust that the vampire feels and the concept of the undead passing its inheritance to the living (Note: In the following excerpt, corse is "corpse"):

- But thou, false Infidel! shalt writhe

- Beneath avenging Monkir's scythe;

- And from its torment 'scape alone

- To wander round lost Eblis' throne;

- And fire unquenched, unquenchable,

- Around, within, thy heart shall dwell;

- Nor ear can hear nor tongue can tell

- The tortures of that inward hell!

- But first, on earth as vampire sent,

- Thy corse shall from its tomb be rent:

- Then ghastly haunt thy native place,

- And suck the blood of all thy race;

- There from thy daughter, sister, wife,

- At midnight drain the stream of life;

- Yet loathe the banquet which perforce

- Must feed thy livid living corse:

- Thy victims ere they yet expire

- Shall know the demon for their sire,

- As cursing thee, thou cursing them,

- Thy flowers are withered on the stem.

Ironically, Byron's own wild life became the model for the protagonist Lord Ruthven in the first vampire novel, The Vampyre (1819) by John William Polidori. Polidori's Lord Ruthven seems to be the first appearance of the modern vampire, an undead, vampiric being possessing a developed intellect and preternatural charm, as well as physical attraction. By contrast, the vampire of folklore was almost invariably thought of as a hideous, unappealing creature.

An unauthorized sequel to Polidori's novel by Cyprien Bérard called Lord Ruthwen ou les Vampires (1820) was adapted by Charles Nodier into the first vampire stage melodrama, which was in turn made into an opera by German composer Heinrich Marschner.

Bram Stoker's Dracula has been the definitive description of the vampire in popular fiction for the last century. Its portrayal of vampirism as a disease (contagious demonic possession), with its undertones of sex, blood, and death, struck a chord in a Victorian England where tuberculosis and syphilis were common.

Dracula appears to be based at least partially on legends about a real person, Vlad Ţepeş (Vlad the Impaler), a notorious Wallachian (Romanian) prince of the 15th century known also as Vlad III Dracula. He was the son of Vlad II Dracul. Vlad II received the title Dracul ("The Dragon") after being inducted into the Order of the Dragon in 1431. In Romanian, Dracul means dragon or devil, and Dracula (or Draculea) means "son of the Dragon" (or "son of the Devil", though "son of the Dragon" was intended in this case). Stoker is believed to have seen a reference in an article by Emily Gerard who said that Dracula was a word meaning the Devil. (Emily Gerard, "Transylvanian Superstitions." Nineteenth Century (July 1885): 130–150). Oral tradition regarding Ţepeş includes his having made a practice of torturing enemy prisoners and hanging them, or parts of them, such as heads, on stakes around his castle or manor house. Ţepeş may have suffered from porphyria. His rumored periodic abdominal agony, especially after eating, and bouts of delirium might indicate presence of the disease.

Stoker also probably derived inspiration from Irish myths of blood-sucking creatures. He also was almost certainly influenced by a contemporary vampire story, Carmilla by Sheridan le Fanu. Le Fanu was Stoker's editor when Stoker was a theatre critic in Dublin, Ireland.

Much 20th-century vampire fiction draws heavily on Stoker's formulation; early films such as Nosferatu and those featuring Bela Lugosi or Christopher Lee are examples of this. Nosferatu, in fact, was clearly based on Dracula, and Stoker's widow sued for copyright infringement and won. As a result of the suit, most prints of the film were destroyed. She later allowed the film to be shown in England.

Though most other works of vampire fiction do not feature Dracula as a character, there is typically a clear inspiration from Stoker, reflected in a fascination with sex and wealth, as well as overwhelmingly frequent use of Gothic settings and iconography. A contemporary descendant is the series of novels by Anne Rice, the most popular in a genre of modern stories that use vampires as their protagonists.

Other vampire tales seen in several places include:

- Varney the Vampire or The Feast of Blood (1845) by James Malcolm Rymer, a Victorian best-seller and pot-boiler

- Carmilla (1872) by Sheridan le Fanu, perhaps the most atmospheric vampire story ever

- Dracula (1897) by Bram Stoker (also the inspiration for many films)

- Nosferatu (1922) (also in a later remake with Klaus Kinski)

- I am Legend (1954) by Richard Matheson. An interesting twist: Vampirism is caused by a bacterium (the use of a wooden stake keeps air in the wound, preventing the bacterium from making repairs), and after the pandemic the hero is the last normal person in a world filled with vampires. It was originally filmed as The Last Man on Earth starring Vincent Price and remade as The Omega Man starring Charlton Heston. The novel was also an inspiration for George Romero's Night of the Living Dead.

- Dark Shadows TV series (1966 and 1991)

- Comic books and graphic novels such as Vampirella (1969), Tomb of Dracula (1972), the aforementioned Blade (1973), and 30 Days of Night (2002). In addition, many major superheroes have faced vampire supervillains at some point.

- 'Salem's Lot (1975) by Stephen King

- The Dracula series of novels (1975–1996) by science fiction author Fred Saberhagen.

- Interview with the Vampire (1976) (also a film) and other books in The Vampire Chronicles, by Anne Rice

- Love At First Bite (1979) a comic spoof of Dracula stories set in the Disco age

- The serials State of Decay (1980) and The Curse of Fenric (1989) from the BBC science fiction television series Doctor Who. Vampires also appear in several novels based on the series, including Blood Harvest (1994) by Terrance Dicks, Goth Opera (1994) by Paul Cornell and Vampire Science (1997) by Jon Blum and Kate Orman, and in the Big Finish audio Project: Twilight (2001) by Cavan Scott and Mark Wright.

- The Hunger (1983) is a film in which genetic material (similar to a virus or prion) is passed from true vampires (a different species) to create temporary vampires (a few centuries or so) from humans. The human vampires act as companions until they eventually wither. Unfortunately for the human vampires, they never die (unless burned) and remain in a conscious, desiccated state (a form of living hell). The lineage of the true vampires begins in ancient times, passes through the Egyptian dynasties, and into the present.

- Fright Night (1985, 1989) (movies)

- The video game series Castlevania (1986–present) is a long-running series in which the protagonist battles a new incarnation of Dracula in every game.

- The Lost Boys (1987) a vampire film set in the youth culture of California - very influential to later films and TV series about vampires

- Brian Stableford's (1988) novel The Empire of Fear, in which an aristocracy of vampires rules the world; ISBN 0330308742.

- Japanese anime and manga features vampires in several titles, including Vampire Princess Miyu (OAV1988,TV series1997),Nightwalker(1998), Vampire Hunter D (2000), Blood: The Last Vampire (2000), Hellsing (2002), Vampire Host (2004), Tsukihime, Lunar Legend (2003) and Tsukuyomi - Moon Phase (2004).

- Role-playing games such as Vampire: The Masquerade (1992), in which the participants play the roles of fictional vampires (for specifics, see vampires in the World of Darkness).

- The Elder Scrolls game series involves vampires, these vampires were created by a daedra prince (demon lord). They have all the typical attributes, but can absorb the 'life force' of an enemy merely by touching their skin. Whenever they try to sleep they are visited by disturbing nightmares.

- Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1992), the TV show of the same name and its television spinoff Angel, a subgenre that features Vampire Hunters or Vampire Slayers, destined to kill or specialized in killing the creatures.

- Forever Knight (1992) is a television series about a vampire/cop who enforces the law to make up for his past misdeeds

- The Undead (1992) and Cold Kiss (1996) by Roxanne Longstreet

- The Season of Passage (1992) by Christopher Pike

- The Anno-Dracula (1992–1998) series by Kim Newman, "what if?" tales extrapolating the events of Dracula if Dracula had not been stopped and had later married Queen Victoria.

- The Darkstalkers (1994) fighting game series (known as Vampire in Japan) features a vampire along with other mythological and horror-themed characters.

- The Anita Blake: Vampire Hunter series (1995-present) by Laurell K. Hamilton, featuring a society where vampires are citizens and a necromantic protagonist.

- From Dusk Till Dawn (1996), a film directed by Robert Rodriguez, cowritten by and featuring Quentin Tarantino. It begins as one of Tarantino's more usual crime stories, but flips halfway through into a vampire film.

- The video game series Legacy of Kain (1996–present) is a five game long series, in which vampires were a wise, ancient race who had their thirst for blood, immortality, and aversion to sunlight inflicted on them by another race called the Hylden.

- Dance of the Vampires (1997) is a musical from Jim Steinman

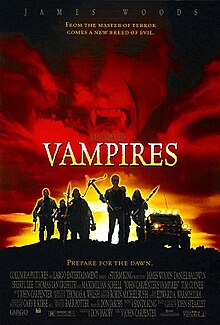

- Vampires (1998), a film by John Carpenter about a divsion of the Vatican devoted to killing vampires (very loosely based on the novel Vampire$ by John Steakley)

- Blade (1998), a comic book and film series, one in a subgenre that features half-human, half-vampire warriors or protagonists.

- Ultraviolet (1998), a British television series about a vampire conspiracy set in 1990s London. The show made a point of using high-tech and scientific approaches to combat the vampires.

- Carpe Jugulum (1998) by Terry Pratchett pastiches the traditions of vampire literature, plays with the mythic archetypes and features a tongue-in-cheek reversal of vampyre subculture with young vampires who wear bright clothes, drink wine, and stay up until noon.

- The comic book series Purgatori (1998–present) (Chaos! Comics): a slavegirl in ancient Egypt becomes a Vampire Goddess.

- Mick Farren's Victor Renquist novels, in which vampires were created by a race of aliens known as the Nephilim

- Jim Butcher's urban fantasy series, The Dresden Files, whose system of magic borrows liberally from various folkloric traditions. White, Red and Black Court vampires all exist, embodying different vampire myths (Black Court being the standard American vampire).

- Brandi Graves' Tempest City: Novelette, in which a half angel must become an fallen angel, (vampire) to save basicly the world.

The "Vampire subculture"

| It has been suggested that this article be merged with Vampire lifestyle. (Discuss) |

The vampire subculture describes a contemporary subculture marked by an obsessive fascination with, and emulation of, contemporary vampire lore, including everything from fashion and music to, in the more extreme cases, the actual exchange of blood. Members of the subculture ("vampirists") often prefer the spelling "vampyre" to distinguish themselves from the "fictional" vampire while simultaneously lending a Victorian flair to their activities. These contemporary consumers of blood typically appeal to myths about vampires for legitimacy.

The subculture is typically delineated by a particular style of dress and decor that combines elements of the Victorian, Punk, Glam and Gothic fashions with styles featured in vampire films and fiction. Although often associated with the Goth subculture, most goths do not enjoy the association with the negative stereotype portrayed in the media and, as a result, actively dislike members of the vampire subculture. Although this subculture is most popular in the United States of America, it has members throughout Europe and eastern Asia.

Most modern practitioners of vampirism do not believe themselves to be undead creatures; rather, they use vampirism as a means of practicing magic(k). For example, they claim that they are taking life energy or qi from another (usually a willing donor who also practices vampirism) to increase their own energy and vitality. Vampirists do not necessarily obtain this energy from blood, but will use other physical, spiritual or psychic means to obtain this energy (for example, there are self-styled "sexual vampires" and "psychic vampires").

A number of these vampires not only practice the drinking of blood but actually believe themselves to be the vampires of legend, or some other supernatural entity (for example, a "lost race" of Homo sapiens); see otherkin for further discussion of this type of phenomenon. Self-styled vampires of this sort will often claim that their own personal physical or psychological characteristics, such as pale skin, sensitive night vision, quick reflexes, emotional irritability and instability, and any number of self-professed psychic abilities are direct results of vampirism rather than independent or imagined traits. Many outside this group see this as a result of a mental illness such as disassociative identity disorder, schizophrenia, or antisocial personality disorder. A few vampiric groups have been likened to cults, and a few self-proclaimed vampires have murdered in order to drink human blood, such as Brisbane's notorious "lesbian vampire murderer" Tracey Wigginton.

It should be noted that consumption of human blood exposes both parties involved to a range of high-risk blood-borne pathogens and diseases.

For more on the topic of modern vampire cults, see vampire lifestyle.

Etymology

English vampire comes from German Vampir, in turn from early Old Polish *vąper' (where ą is a nasal a, and both p and r' are palatalized), in turn from Old Slavic *oper (with a nasal o) or Old Church Slavonic opiri. According to Slavic linguist Franc Miklošič, the word ultimately comes from Kazan Tatar ubyr "witch".

Further reading

- Christopher Frayling - Vampyres: Lord Byron to Count Dracula 1992. ISBN 0571167926

See also

- Chinese vampire

- Dracula

- Elizabeth Bathory

- Energy vampire

- List of vampire movies

- Maschalismos

- Medieval revenants

- The Mercy Brown Vampire Incident

- Psychic vampire

- Vampire bats

- Vlad III Dracula

External links

- Drink Deeply and Dream: The Reality of the Modern-Day Vampire

- Vampire Posers

- Staking Claims: The Vampires of Folklore and Fiction

from: Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal - Vampires from: The New England Skeptical Society

- Mother of "vampire cult" leader pleads guilty from: F.A.C.T.Net

- Vampiremania

- Pseudoscience of vampirism and DVD listings.

- An extensive list of vampire movies.

- Professor Elizabeth Miller has written books and articles on Stoker's Dracula and Vlad Tepes.

- Darkness Embraced Vampire and Occult Society Interactive real vampire society and occult practitioners

- The Vampire Donor Alliance is a place for real blood drinkers and blood donors to communicate.

- Sanguinarius is a page providing support for a presumed group of real vampires.

- SphynxCat's Real Vampires Support Page is another site providing support for a presumed group of real vampires.

- Temple of the Vampire “Test Everything. Believe Nothing.”

- Vampires.com is a massive community for vampires and other alternative lifestyles

- Morsure.net is a fun French place about vampires. Literature, cinema, society, art, geography.

- The saga of Petar Blagojevic

- Knots, Threads, Spinning, and Vampires

- Vampiric Studies is a site by Catherene NightPoe containing a vast amount of information regarding vampires.

- The Polidori Files The web's first link portal devoted entirely to John William Polidori, author of "The Vampyre".