This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Wyss (talk | contribs) at 01:29, 26 July 2005 (my suggestion). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:29, 26 July 2005 by Wyss (talk | contribs) (my suggestion)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) "Hitler" redirects here. For other persons of the same name, see Hitler (disambiguation).| Adolf Hitler | |

|---|---|

| Born | April 20, 1889 Braunau am Inn, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | April 30, 1945 Berlin, Germany |

Adolf Hitler (April 20, 1889 – April 30, 1945) was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 until his death. He was also Führer of the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP), better known as the Nazi Party.

At the height of their power, the armies of Nazi Germany and its Axis Powers dominated much of Europe during World War II. The racial policies that Hitler directed culminated in a massive number of deaths, commonly cited as at least 11 million people — including 6 million Jews, in a genocide now known as the Holocaust.

Under Hitler's leadership, Germany ascended from the depths of post-World War I defeat and economic crisis to become one of the world's most powerful nations. However, it was defeated by the Allied powers in 1945 and during the final days of the war Hitler committed suicide in an underground bunker in Berlin. The Third Reich, which he had said would last a thousand years, collapsed shortly thereafter.

Early life

Childhood

Adolf Hitler was born on April 20 1889 at Braunau am Inn, Austria, a small town 90 km (55 miles) west of Linz in the province of Upper Austria, not far from the German border in what was then Austria-Hungary. He was the fourth of six children of Alois Hitler (1837–1903), a customs official, and Klara Pölzl, Alois' niece and third wife. Of these six children, only Adolf and his younger sister Paula reached adulthood. Alois Hitler also had a son (Alois Junior) and a daughter (Angela) by his second wife. In Mein Kampf, his autobiography, Adolf Hitler describes his father as an "irascible tyrant"; however, there is little indication that Alois Hitler treated his son more strictly than was usual for that time and place.

Alois Hitler was born out of wedlock, and, until he was 40, used his mother's surname, Schicklgruber. In 1876, he began using the name of his stepfather, Johann Georg Hiedler, after visiting a priest responsible for birth registries and declaring that Georg was his father (Alois gave the impression that Georg was still alive, but he was long dead). The spelling was probably changed by a clerk. Later, Adolf was accused by his political enemies of not rightfully being a Hitler, but a Schicklgruber. This was also exploited in Allied propaganda during the Second World War when pamphlets bearing the phrase "Heil Schicklgruber" were airdropped over German cities. He was legally born a Hitler, however, and was closely related to Hiedler through his mother's family, too.

Hitler did not know for sure who his paternal grandfather was, but it was probably either Johann Georg Hiedler or his brother Johann von Nepomuk Hiedler. There have been rumours that Hitler was one-quarter Jewish and that his paternal grandmother Maria Schicklgruber had become pregnant after working as a servant in a Jewish household in Graz. During the 1920s, the implications of this along with his known family history were politically explosive, especially for the proponent of a racist ideology. Opponents tried to prove that Hitler, the leader of the anti-Semitic and jingoistic Nazi Party, had Jewish or Czech ancestors. Although these rumours were never confirmed, for Hitler they were reason enough to conceal his origins. Soviet propaganda insisted he was a Jew, though newer research tends to diminish the probability Hitler had Jewish or Czech ancestors. Historians such as Werner Maser and Ian Kershaw argue this was impossible since the Jews had been expelled from Graz in the 15th century and were not allowed to return until well after Maria Schicklgruber's alleged employment. Because of Alois Hitler's profession his family moved frequently, from Braunau to Passau, Lambach, Leonding and next to Linz. Young Adolf was reportedly a good student at the various elementary schools he attended; however, in sixth grade (1900–1901), his first year of high school (Realschule) in Linz, he failed completely and had to repeat the grade. His teachers reported that he had "no desire to work."

Hitler later explained this as a kind of rebellion against his father Alois, who wanted the boy to follow him in a career as a customs official, although Adolf wanted to become a painter. This is further supported by Hitler's later description of himself as a misunderstood artist. After Hitler's father died on January 3, 1903, at age 65, Adolf Hitler's schoolwork did not improve. At the age of 16, Hitler left school without graduating.

Early adulthood in Vienna and Munich

From 1905 onward, Hitler was able to live the life of a Bohemian on a fatherless child's pension and support from his mother. After he was rejected twice by the Academy of Arts in Vienna (1907–1908) for "lack of talent"—which he resented deeply—he did not try to find a different job or learn a profession. He was told he should become an architect, since he had some flair for painting buildings. On December 21, 1907, his mother Klara died a painful death from breast cancer. He gave his share of the orphans' benefits to his younger sister Paula, but soon after inherited some money from an aunt. He worked as a struggling painter in Vienna, copying scenes from postcards and selling his paintings to merchants and tourists (there is evidence he produced over 2000 paintings and drawings before World War I).

It was in Vienna that Hitler began to turn into an active anti-Semite, which was a common stance among Austrians at the time and deeply ingrained in the Catholic culture that Hitler grew up in. Vienna had a large Jewish community, including many Orthodox Jews from Eastern Europe. He was influenced by the pseudoscientific and neo-religious writings of the race ideologist and anti-Semite Lanz von Liebenfels and polemics from politicians such as Karl Lueger, the Mayor of Vienna, and Georg Ritter von Schönerer, the leader of the pan-Germanistic movement. Hitler acquired a belief in the superiority of the "Aryan race," which formed the basis of his political views. He began to claim the Jews were natural enemies of "Aryans" and were responsible for Germany's economic problems. However, according to August Kubizek, his close friend and roommate at the time, he was more interested in the operas of Richard Wagner than in politics.

After the second refusal from the Academy of Arts, Hitler gradually ran out of money. By 1909, he sought refuge in a homeless shelter, and by the beginning of 1910 had settled permanently into a house for poor working men. He made spending money by painting tourist postcards of Vienna scenery. His anti-Semitism during this period has been debated somewhat, since a Jewish resident of the house named Hanisch was helping him sell his postcards— seemingly contrary to statements he later made in Mein Kampf.

He was given a small inheritance from his father in May 1913 and moved to Munich. He later wrote in Mein Kampf that he had always longed to live in a German city. In Munich, he became more interested in architecture and the racist writings of Houston Stewart Chamberlain. Moving to Munich also helped him escape military service in Austria for a time, but the Austrian army later arrested him. After a physical exam (during which his height was measured at 1.73 m, or 5 ft 8 in) and a contrite plea, he was found unfit for service and allowed to return to Munich. However, when Germany entered World War I in August 1914, he immediately enlisted in the Bavarian army.

World War I

Hitler saw active service in France and Belgium as a messenger for the 16th Bavarian reserve infantry regiment, which exposed him to enemy fire. He also drew some cartoons and instructional drawings for the army newspaper. He was twice cited for bravery in action, receiving the Iron Cross, Second Class, in December 1915 and the Iron Cross, First Class in August 1918. (This was an honour rarely given to lance corporals. The fact that he was not a German citizen at that time, and therefore could not be promoted beyond corporal, might have been significant.) In October 1916, in northern France, Hitler was wounded in the leg. At the beginning of March 1917 he returned to the front.

Hitler was considered a "correct" soldier but was reportedly unpopular with his comrades because of an uncritical attitude towards officers. "Respect the superior, don't contradict anybody, obey blindly," he said, describing his attitude while on trial for his Beer Hall Putsch in 1924. One comrade later remarked, "we all grumbled on him and found it intolerable that we had a white raven among us." (Haiden, 1936)

On October 15, 1918, shortly before the end of war, Hitler was admitted to a field hospital, temporarily blind following a poison gas attack. Recent research by Bernhard Horstmann however indicates the blindness may have been the result of a hysterical reaction to Germany's military defeat. Hitler was treated by a military physician who specialised in psychiatry. He reportedly diagnosed the corporal as "incompetent to command people" and "dangerously psychotic." His commander at the time said, "I will never promote this hysteric!" (cited from Haiden, 1937). However, historian Sebastian Haffner refers to Hitler's experience at the front as his only education and suggests he did have at least some understanding of the military.

During the war, Hitler became a passionate German patriot, although he did not become a German citizen until 1932. He was shocked by the capitulation of Germany in November 1918 while the German army remained (in popular German belief) undefeated. Like many other German nationalists, Hitler blamed civilian politicians (the "November criminals") for the surrender. The widespread right-wing, conservative explanation for the capitulation was the Dolchstosslegende ("dagger-stab legend") which purported that behind the backs of the army, liberal politicians had betrayed and "stabbed" Germany's people and its soldiers "in the back." The Treaty of Versailles imposed crippling reparations and declared Germany guilty for the Great War horrors; thus was perceived by most Germans as a humiliation and was an important factor in the social conditions encountered by Hitler and his party in seeking power.

Weimar Republic

Early Nazi Party

Main article: Hitler's political beliefsAfter the war, Hitler remained in the army, which was mainly engaged in suppressing socialist uprisings breaking out across Germany, including Munich, where Hitler returned in 1919. He took part in "national thinking" courses organised by the Education and Propaganda Department (Dept Ib/P) of the Bavarian Reichswehr Group, Headquarters 4 under Captain Mayr. A key purpose of this group was to create a scapegoat for the outbreak of the war and Germany's defeat. The scapegoats were found in "international Jewry," communists and politicians across the party spectrum.

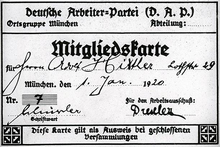

In July 1919, Hitler was appointed a V-Mann (Verbindungsmann is the German term for a police spy) of "Aufklärungskommando" ("Intelligence Commando") of the Reichswehr, for the purpose of influencing other soldiers towards similar ideas and was assigned to infiltrate a small nationalist party, the German Workers' Party (DAP). Here Hitler met Dietrich Eckart, one of the early founders of the party.

Hitler was discharged from the army in 1920 and (with the army's continued encouragement) began participating full time in the party's activities. He soon became its leader and changed its name to the National Socialist German Workers Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, NSDAP), usually known as the Nazi party .

Hitler's street-corner oratory, attacking Jews, socialists and liberals, capitalists and Communists, began attracting adherents. Early followers included Rudolf Hess, Hermann Göring, and Ernst Röhm, head of the Nazis' paramilitary organisation, the SA. Another admirer was wartime General Erich Ludendorff. Hitler decided to use Ludendorff as a front in an attempt to seize power in Munich, the capital of Bavaria, in an abortive coup later known as the "Hitler Putsch" or "March to Berlin" of November 8, 1923. The Nazis marched from a beer hall to the Bavarian War Ministry, intending to overthrow Bavaria's right-wing separatist government and then march on Berlin. The army quickly dispersed them and Hitler was arrested. To protect his own position, Hitler appointed Alfred Rosenberg as temporary leader of the group.

Upon being arrested, Hitler found himself in an environment somewhat receptive to his beliefs. During his trial for high treason in April 1924, sympathetic conservative magistrates left over from pre-Weimar allowed Hitler to turn the debacle into a propaganda stunt. Hitler was allotted unlimited amounts of time to present his arguments to the courts as well as a large body of the German people, and gave his popularity a boost by voicing sentiments shared by the public. For a crime of conspiracy against his nation, Hitler was sentenced to five years' imprisonment at Landsberg prison, where he received favoured treatment from the guards and had much fan mail from admirers. While at Landsberg he dictated his political book Mein Kampf (My Struggle) to his deputy Rudolf Hess. The first volume, called "Abrechnung" (payback), was later published and became the platform of the Nazi party (by the late 1930s nearly every household in Germany had a copy of it). Meanwhile, as he was considered relatively harmless, Hitler was given an early amnesty and was released in December 1924. By this time the Nazi party had dwindled and Hitler began a long effort to rebuild it.

A key element of Hitler's appeal was his ability to convey a sense of offended national pride caused by the Treaty of Versailles imposed on the defeated German Empire by the Allies. Germany had lost territory in Europe and its colonies, had had to admit to sole responsibility for the war and pay a huge reparations bill totaling $6,600,000 (32 billion marks). Most Germans bitterly resented these terms, but early attempts to gain support by blaming these humiliations on "international Jewry" were not particularly successful with the electorate. The party learned quickly and soon a more subtle propaganda emerged, combining anti-Semitism with an attack on the failures of the "Weimar system" and the parties supporting it.

In 2004, it was discovered that Hitler had spent years evading taxes on income from sales of Mein Kampf. He owed the German government 405,000 Reichmarks (equivalent to $8 million at 2004 exchange rates) by the time he took power and the tax debt was forgiven.

The road to power

See also the Weimar Timeline.

The political turning point for Hitler came with the Depression which hit Germany in 1930. The democratic regime established in Germany in 1919 (the Weimar Republic) had never been accepted by conservatives and was openly opposed by fascists. The Social Democrats and traditional parties of the centre and right were unable to cope with the shock of the Depression. In the September 1930 elections the Nazis suddenly rose from relative obscurity to win 18.3% of the vote along with 107 seats in the Reichstag, becoming the second largest party in Germany.

Hitler appealed to the bulk of German farmers, war veterans and the middle-class, who had been hard-hit by both the inflation of the 1920s and the unemployment of the Depression. The urban working classes generally ignored Hitler's appeals and Berlin and the Ruhr towns were particularly hostile. The 1930 election was a disaster for Heinrich Brüning's centre-right government, which was now deprived of a majority in the Reichstag.

Meanwhile in December 1931 Hitler's niece Geli Raubal was found dead in her bedroom in his Munich apartment (his half-sister Angela and her daughter Geli had been with him in Munich since 1929), an apparent suicide. Geli was much younger than he was, and she had used his gun, drawing rumours of a relationship between the two. There is still speculation regarding the circumstances of her death, which is viewed as an event of lasting turmoil for Adolf, and is often stated as the source of his claimed vegetarianism.

While Brüning's austerity measures were bringing little economic improvement, the government was anxious to avoid a presidential election in 1932 and hoped to secure Nazi agreement to an extension of President Paul von Hindenburg's term. Hitler refused and ultimately competed against Hindenburg in the 1932 presidential election, coming in second on both rounds of the election. He attained more than 35% of the vote during the second round in April.

Hindenburg dismissed the government, appointing a new one under the conservative Franz von Papen, which immediately called for new Reichstag elections. In July 1932 the Nazis had their best election showing yet, winning 230 seats and becoming the largest party in the Reichstag. Since the Nazis and the communists now together controlled a majority of the Reichstag, the formation of a stable government of mainstream parties had become impossible. After a vote of no-confidence in the Papen government, supported by 84% of the delegates, the new Reichstag was dissolved and new elections were called.

Papen and the Centre Party (Zentrumspartei) began negotiations to secure Nazi participation in the new government but Hitler set high terms, demanding the Chancellorship along with the President's agreement that he be able to use emergency powers. The offer was rebuffed, and combined with the Nazis' failure to win working class support, some Nazi supporters were alienated. During the November 1932 elections the Nazis lost votes although they remained by far the largest party in the Reichstag. Since Papen had failed to secure a majority, Hindenburg dismissed him and appointed General Kurt von Schleicher, who promised he could secure a majority government by negotiations with both Social Democratic labour unions and the dissident Nazi faction led by Gregor Strasser.

In November 1932, Fritz Thyssen, Hjalmar Schacht and other leading German businessmen appealed to Hindenburg in a letter to appoint Hitler as leader of a non-democratic government "independent from parliamentary parties" which could turn into a movement that would "enrapture millions of people." Finally, Papen and Alfred Hugenberg (Chairman of the German National People's Party, the DNVP, which before the Nazis were Germany's principal right-wing party) conspired to persuade Hindenburg to appoint Hitler Chancellor in a coalition with the DNVP, promising they would be able to control him. When Schleicher was forced to admit failure in his efforts to form a coalition and asked Hindenburg for yet another Reichstag dissolution, Hindenburg fired him and appointed Hitler Chancellor, Papen Vice-Chancellor and Hugenberg Minister of Economics in a cabinet which included only three Nazis, Hitler, Göring and Wilhelm Frick. On January 30, 1933 Adolf Hitler was officially sworn in as Chancellor in the Reichstag chamber with thousands of Nazi supporters looking on and cheering.

After the Reichstag was set on fire (and the communists were blamed for it), the Reichstag Fire Decree suspended civil liberties. Subsequently, in the March 1933 elections the Nazis received 43.9% of the vote. The party gained control of a majority of seats in the Reichstag through a formal coalition with the DNVP. The Enabling Act, passed by the Reichstag after the Nazis expelled the Communist deputies, gave Hitler dictatorial authority. Under the Enabling Act the Nazi cabinet had the power to pass legislation just as the Reichstag did. The Act further specified that the cabinet could only approve measures submitted by the Chancellor (Hitler) and that it would lapse after four years time or upon the installation of a new government. The Enabling Act was dutifully renewed every four years, even during World War II.

A series of decrees followed soon after the passage of the Enabling Act. Other parties were suppressed and all opposition was banned. In only a few months Hitler had achieved authoritarian control. President Paul von Hindenburg died on August 2, 1934. Rather than have new presidential elections, Hitler's cabinet passed a law combining the offices of President and Chancellor, with Hitler holding both offices (including the President's decree powers) as "Leader and National Chancellor." This consolidation was claimed by the Nazis to be approved by the electorate in what was actually a show election (the outcome was 90% "approval") in mid-August 1934. Then, in an unprecedented step, Hitler ordered every member of the military to swear a personal oath of allegiance to him.

The Third Reich

See also Nazi Germany

Having secured supreme political power without an electoral mandate from the majority of Germans, Hitler went on to gain their support and remained overwhelmingly popular until the very end of his regime. He was a master orator and with all of Germany's mass media under the control of his propaganda chief, Dr. Joseph Goebbels, he persuaded most Germans he was their saviour from the Depression, the Communists, the Versailles Treaty and the Jews. The government declared itself the Third Reich (Empire), a successor state to the earlier Holy Roman and Prussian empires. The Reich was planned to last for a "thousand years".

Economics and culture

Hitler oversaw one of the greatest expansions of industrial production and civil improvement Germany had ever seen, mostly based on debt flotation and expansion of the military. Nazi policies towards women strongly encouraged them to stay at home to bear children and keep house. The unemployment rate was cut substantially, mostly through arms production and sending women home so that men could take their jobs. Given this, claims that the German economy achieved near full employment are at least partly artifacts of propaganda from the era.

Hitler also oversaw one of the largest infrastructure improvement campaigns in German history, with the construction of dozens of dams, autobahns, railroads and other civil works. Hitler's policies emphasised the importance of family life: Men were the "breadwinners", while women's priorities were to be "church, kitchen and children", in German Kirche, Küche und Kinder or "Drei K" (three K's).

Hitler's government sponsored architecture on an immense scale, with Albert Speer becoming famous as the first architect of the Reich. In 1936 Berlin hosted the summer Olympic games, which were opened by Hitler and choreographed to demonstrate Aryan superiority over all other races. Olympia, the movie about the games and documentary propaganda films for the German Nazi Party were directed by Hitler's personal film-maker Leni Riefenstahl.

Although Hitler made plans for a Breitspurbahn (broad gauge railroad network), they were pre-empted by World War II. Had the railroad been built, its gauge would have been three meters, even wider than the old Great Western Railway of Britain.

In 1932 Hitler was instrumental in initiating the design work on the car that later became the Volkswagen Beetle.

Repression

For the unpersuaded, the SA, SS and Gestapo (secret state police) were given a free hand. Thousands disappeared into concentration camps. Many thousands more emigrated, including about half of Germany's Jews.

By 1934 Ernst Röhm's SA had become unpopular with most of the other influential political and military groups in Germany. Hitler ordered his lieutenant Himmler to murder Röhm, once called "Hitler's only true friend", and dozens of other real and potential enemies during the night of June 29, 1934, the Night of the Long Knives.

Under the 1935 Nuremberg Laws, Jews lost their German citizenship and were expelled from government employment, the professions and most forms of economic activity. They were also subject to a barrage of hate propaganda. Few non-Jewish Germans objected to these steps. Restrictions were further tightened later, particularly after the 1938 anti-Jewish operation known as Kristallnacht. From 1941 Jews were required to wear a yellow star in public. Between November 1938 and September 1939 more than 180,000 Jews fled Germany and the Nazis seized whatever property they left behind.

Rearmament and new alliances

In March 1935 Hitler repudiated the Treaty of Versailles by reintroducing conscription in Germany. He set about building a massive military machine, including a new Navy (the Kriegsmarine) and an Air Force (the Luftwaffe). The enlistment of vast numbers of men and women in the new military seemed to solve unemployment problems but seriously distorted the economy.

In March 1936 he again violated the Treaty of Versailles by reoccupying the demilitarised zone in the Rhineland. When Britain and France did nothing, he grew bolder. In July 1936 the Spanish Civil War began when the military, led by General Francisco Franco, rebelled against the elected Popular Front government of Spain. Hitler sent troops to support Franco and Spain served as a testing ground for Germany's new armed forces and their methods, including the bombing of undefended towns such as Guernica, which was destroyed by the Luftwaffe in April 1937, prompting Pablo Picasso's famous eponymous painting (see Guernica (painting)).

An Axis was declared between Germany and Italy by Galeazzo Ciano, foreign minister of Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini on October 25, 1936. This alliance was later expanded to include Japan, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria. They were collectively known as the Axis Powers. Then on November 5, 1937 at the Reich Chancellory, Adolf Hitler held a secret meeting and stated his plans for acquiring "living space" (Lebensraum) for the German people.

The Holocaust

Main article: Holocaust

Between 1939 and 1945 the SS, assisted by collaborationist governments and recruits from occupied countries, systematically killed at least 11 million people (other estimates are as high as 26 million; 6 million of whom were Jews) in concentration camps, ghettos and mass executions, or through less systematic methods elsewhere. Besides being gassed to death, many also died of starvation and disease while working as slave labourers. Along with Jews, alleged communists or political opposition, homosexuals, dissenting Roman Catholics and Protestants, Roma, the physically handicapped and mentally retarded, Soviet prisoners of war, Poles, Jehovah's Witnesses, anti-Nazi clergy, trade unionists, and psychiatric patients were killed. The industrial-scale genocide of Jews in Europe during this period is referred to as the Holocaust.

The massacres that led to the coining of the word "genocide" (the Endlösung or "Final Solution") were planned and ordered by leading Nazis, with Himmler playing a key role. While no specific order from Hitler authorising the mass killing of the Jews has surfaced, there is documentation he approved the Einsatzgruppen and the evidence also suggests that sometime in the fall of 1941 Himmler and Hitler agreed in principle on mass murder by gassing. During interrogations by Soviet intelligence officers declassified over fifty years later, Hitler's valet Heinz Linge and his military aide Otto Gunsche said Hitler had "pored over the first blueprints of gas chambers."

To make for smoother intra-governmental cooperation in the implementation of this "Final Solution" to the "Jewish question", the Wannsee conference was held near Berlin on January 20, 1942 with fifteen senior officials participating, led by Reinhard Heydrich and Adolf Eichmann. The records of this meeting provide the clearest evidence of central planning for the Holocaust. Days later, on February 22, Hitler was recorded saying to his closest associates "we shall regain our health only by eliminating the Jews".

World War II

Opening moves

On March 12, 1938 Hitler pressured his native Austria into unification with Germany (the Anschluss) and made a triumphal entry into Vienna. Next he intensified a crisis over the German-speaking Sudetenland district of Czechoslovakia. This led to the Munich Agreement of September 1938, which British prime minister Neville Chamberlain hailed as "Peace in our time". At Munich, Britain and France had weakly given way to his demands, averting war but failing to save Czechoslovakia. As a result of the summit Hitler was Time Magazine's Man of the Year in 1938.

Hitler ordered Germany's army to enter Prague on March 10, 1939, claiming territories ceded to Poland under the Versailles Treaty. Britain had not been able to reach an agreement with the Soviet Union for an alliance against Germany, and, on August 23, 1939, Hitler concluded a secret non-aggression pact (the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) with Stalin. On September 1 Germany invaded Poland. Britain and France, who had guaranteed assistance to Poland, declared war on Germany.

After conquering Poland by the end of September, Hitler built up his forces much further during what was colloquially called the Sitzkrieg (sitting war). The Sitzkrieg ended in March 1940 when he ordered German forces to march into Denmark and Norway. In May 1940, Hitler ordered his forces to attack France, conquering the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Belgium in the process. France surrendered on June 22, 1940. This string of victories convinced his main ally, Benito Mussolini of Italy, to join the war on Hitler's side in May 1940.

Britain, whose forces had been driven from France at the coastal town of Dunkirk, continued to fight on alone. After having his overtures for peace systematically rejected by the British Government, now led by Winston Churchill, Hitler ordered bombing raids on the British Isles, leading to the Battle of Britain, which was meant to be the prelude of a German invasion. However, the RAF defeated the Luftwaffe by the end of October 1940, and Hitler therefore ordered bombing raids to be carried out on British cities, including London and Coventry, mostly at night. This was the so-called Blitz and it lasted until May 1941.

On June 22, 1941 Hitler gave the signal for three million German troops to attack the Soviet Union, breaking the non-aggression pact he had concluded with Stalin less than two years earlier. This invasion, called Operation Barbarossa, seized huge amounts of territory, especially the Baltic states and Ukraine, resulting in the destruction of many Soviet forces. German forces were stopped short of Moscow in December 1941 by a harsh winter and fierce Soviet resistance, however (see Battle of Moscow), and the invasion failed to achieve the quick triumph over the Soviet Union which Hitler had anticipated.

Path to defeat

Hitler's declaration of war against the United States on December 11, 1941, (which arguably was called for by Germany's treaty with Japan) set him against a coalition that included the world's largest empire (the British Empire), the world's greatest industrial and financial power (the USA), and the world's largest nation (the Soviet Union).

In late 1942, German forces under Feldmarschall Erwin Rommel were defeated in the battle of El Alamein, thwarting Hitler's plans to seize the Suez Canal and the Middle East. In February of 1943, the months-long Battle of Stalingrad ended with the complete destruction of the German forces there by armies of the Soviet Union. Both defeats were turning points in the war. After these, the quality of Hitler's military judgement became increasingly erratic and Germany's military and economic position deteriorated. His health was deteriorating too. His left hand started shaking uncontrollably. The biographer Ian Kershaw believes he suffered from Parkinson's disease. Other conditions that are suspected by some to have caused some (at least) of his symptoms are methamphetamine addiction and syphilis.

Hitler's ally Benito Mussolini was overthrown in 1943 after British and American forces invaded Sicily. Throughout 1943 and 1944, the Soviet Union steadily forced Hitler's armies into retreat along the eastern front. On June 6, 1944 (D-Day) the Western allied armies landed in northern France. Realists in the German army knew defeat was inevitable and some officers plotted to remove Hitler from power. In July 1944 one of them, Claus von Stauffenberg, planted a bomb at Hitler's military headquarters (the so-called July 20 Plot), but Hitler narrowly escaped death. Savage reprisals followed, resulting in the executions of more than 4,000 people (often by starvation in solitary confinement followed by slow strangulation). The resistance movement was crushed.

Defeat and death

- Main article: Hitler's death

By the end of 1944 the Soviets had driven the last German troops from their territory and began charging into Central Europe. The western armies were advancing into Germany. The Germans had lost the war from a military perspective but Hitler allowed no peace talks with the Allied forces and as a consequence the German military continued to fight. By April 1945 Soviet forces were at the gates of Berlin. Hitler's closest lieutenants urged him to flee to Bavaria or Austria to make a last stand in the mountains but he was determined to die in his capital. The leader of SS Heinrich Himmler tried on his own to inform the Allies with the help of a Swedish diplomat that Germany was prepared to surrender. Hitler got news of this through Swedish radio.

As Soviet troops battled their way toward his Reich Chancellory in the centre of the city, Hitler is generally believed to have committed suicide in his Führerbunker on 30 April 1945 in Berlin by means of a self-delivered shot to the head (some disputed accounts add that he simultaneously bit into a cyanide ampoule). Hitler's body and that of Eva Braun, his long-term mistress whom he had married the day before, were partially burned with gasoline and buried shortly thereafter in the Chancellory garden.

When Russian forces reached the Chancellory, they exhumed his body and performed an autopsy, using dental records (and German dental assistants who were familiar with them) to confirm the identification. To avoid any possibility of creating a potential shrine, the remains were then secretly buried by SMERSH at their new headquarters in Magdeburg. In April 1970, when the facility was about to be turned over to the East German government, the remains were reportedly exhumed, thoroughly burned and disposed of in the Elbe river. In Moscow there is a skull and a mandible fragment which is said to be Hitler's (having been saved from the dental identification process). DNA samples have been compared to those of known surviving Hitler relatives and the matching results indicate the fragment is most likely genuine.

Legacy

I would have preferred it if he'd followed his original ambition and become an architect. - Paula Hitler (his younger sister), during an interview with a US intelligence operative in late 1945.

After visiting these two places (Hitler’s mountain home and the lair) you can easily see how that within a few years Hitler will emerge from the hatred that surrounds him now as one of the most significant figures who ever lived.

He had boundless ambition for his country, which rendered him a menace to the peace of the world, but he had a mystery about him in the way that he lived and in the manner of his death that will live and grow after him. He had in him the stuff of which legends are made. - John F. Kennedy, The Post-War Diary of, Prelude to Leadership (pages 73-74, last two paragraphs).

At the time of Hitler's death most of Germany's infrastructure and major cities were in ruins and he had left explicit orders to complete the destruction. Millions of Germans were dead with millions more wounded or homeless. In his will he dismissed other Nazi leaders and appointed Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz as Reichspräsident (President of Germany) and Goebbels as Reichskanzler (Chancellor of Germany). However, Goebbels and his wife Magda committed suicide on 1 May 1945. On 8 May 1945 in Reims, France the German armed forces surrendered unconditionally ending the war in Europe and with the creation of the Allied Control Council on 5 June 1945 the Four Powers assumed "supreme authority with respect to Germany." Adolf Hitler's proclaimed Thousand Year Reich had lasted 12 years.

Since the defeat of Germany in World War II, Hitler, the Nazi Party and the results of Nazism have been regarded in most of the world as synonymous with evil. Historical and cultural portrayals of Hitler in the west are almost uniformly negative, often neglecting to mention the adulation the German people bestowed on Hitler during his lifetime, though the majority of present-day Germans share a negative view of Hitler.

The copyright of Hitler's book Mein Kampf is currently held by the Free State of Bavaria, which does not allow reproductions. The copyright will expire in 2015. The display of swastikas or other Nazi symbols is prohibited and right and left wing extremists are generally under surveillance by the Verfassungsschutz, the federal office for the protection of the constitution.

Despite this there have been instances of public figures referring to his legacy in neutral or even favourable terms, particularly in South America, the Islamic World and parts of Asia. Future Egyptian President Anwar Sadat wrote favourably of Hitler in 1953. Bal Thackeray, leader of the right-wing Shiv Sena party in the Indian state of Maharashtra, declared in 1995 that he was an admirer of Hitler.

While some Revisionist historians note Hitler's attempts to improve the economic and political standing and conditions of his people and claim his tactics were in essence no different from those of many other leaders in history, his methods and legacy, as interpreted by most historians, have caused him to be one of the most despised leaders in history.

See also: Consequences of German Nazism and Neo-Nazism.

Medical health

Main article: Adolf Hitler's medical health

Hitler's medical health has long been the subject of debate, and he has variously been suggested to have suffered from irritable bowel syndrome, skin lesions, irregular heartbeat, tremors on the left side of his body, syphilis, Parkinson's disease and addiction to methamphetamines.

Hitler's family

See also: Hitler (disambiguation)

- Eva Braun, mistress and then wife

- Alois Hitler, father

- Klara Hitler, mother

- Paula Hitler, sister

- Alois Hitler, Jr., half-brother

- Bridget Dowling, sister-in-law

- William Patrick Hitler, nephew

- Angela Hitler Raubal, half-sister

- Geli Raubal, niece and rumoured mistress

- Maria Schicklgruber, grandmother

- Johann Georg Hiedler, presumed grandfather

- Johann von Nepomuk Hiedler, maternal great-grandfather, presumed great uncle and possibly Hitler's true paternal grandfather

The origin of the name "Hitler"

There are two theories about the origin of the name "Hitler":

- (1) From German Hüttler and similar, "one who lives in a hut", "shepherd".

- (2) From Slavonic Hidlar and Hidlarcek and similar.

Trivia

- The archives of the Finnish Yleisradio broadcasting company contain an audio tape segment of a Hitler conversation with Finnish Marshal Mannerheim and other high military officers which may be the only known recording of Hitler speaking in a conversational tone of voice rather than with the intense delivery he used for official speeches. It was recorded secretly by Finnish military when Hitler surprisingly flew to Finland to congratulate Marshall Mannerheim on his 75th birthday, 4 June 1942.

- The 2004 film Der Untergang (Downfall) is partly based on the autobiography of Traudl Junge, a favorite secretary of Hitler's. In 2002 Junge said she felt great guilt for "...liking the greatest criminal ever to have lived."

- In response to a shortage of servants during the war, Hitler is reported to have said, "I stamp whole divisions into the dirt! And I can't get a few more serving wenches for the Berghof? Organise it now!"

Hitler's associates

- Martin Bormann, Adolf Hitler's Private Secretary.

- Hans Frank, Hitler's lawyer and later senior Nazi official in occupied Poland.

- Joseph Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda, 25th Chancellor of Germany.

- Hermann Goering, founder of the Gestapo.

- Rudolf Hess, one-time Deputy Leader of the Nazi Party, best known for his flight to Scotland to negotiate peace in 1941.

- Reinhard Heydrich, considered as a possible successor by Hitler, assassinated by a team of Czech agents on May 27, 1942.

- Heinrich Himmler, leader of the SS, key figure in the Holocaust and the "Final Solution".

- Alfred Jodl, military officer, knew Hitler since 1923.

- Wilhelm Keitel, military Field Marshal during World War II.

- Ernst Röhm, leader of the SA, shot on Hitler's orders in the Night of the Long Knives.

- Albert Speer, minister of armament.

- Paul Troost, famous architect.

see also

Media

Template:Multi-video start Template:Multi-video item Template:Multi-video end

Notes

- "'Heil Schicklgruber!'???," about.com (accessed June 11, 2005); Cecil Adams, "Was Hitler part Jewish?," The Straight Dope (accessed June 11, 2005).

- Joachim C. Fest, "The Drummer," in The Face Of The Third Reich (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1970; accessed June 11, 2005).

- Adolf Hitler and Volkswagen, Hitler Historical Museum, 1999 (accessed June 11, 2005).

- "How many Jews were murdered in the Holocaust? How do we know? Do we have their names?," from FAQs About The Holocaust, Yad Vashem (accessed June 11, 2005); "The Holocaust," Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (accessed June 11, 2005).

- "11-million perished," St. Petersburg Times, 1999 (accessed June 11, 2005); Karen Silverstrim, "Overlooked Millions: Non-Jewish Victims of the Holocaust," University of Central Arkansas (accessed June 11, 2005).

See also

- Anti-Semitism

- Hitler in popular culture

- Nazi mysticism

- Hitler's death

- Members of Hitler's cabinet

- Nero Decree

- Widerstand, the resistance movements in Nazi Germany

- Hitler and the church

- Early Nazi Timeline focuses on the rise of Hitler

- Nazi architecture

- Nazi Germany

References

- The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, William L. Shirer (1960). Gramercy. (ISBN 0517102943)

- Doron Arazi, Adolf Hitler: A Bibliography, Greenwood, 1994, ISBN 0-877-36360-1

- Alan Bullock, Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives, HarperCollins, 1991, ISBN 0679729941

- Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny, ISBN 0060920203

- Joachim Fest, Hitler, Harvest Books, 2002, ISBN 0156027542

- Brigitte Hamann, Thomas Thornton, Hitler's Vienna, Oxford University Press; New Ed edition, 2000

- Eberhard Jäckel, 1981, Hitler's World View: A Blueprint for Power, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- (Kershaw 1999): Ian Kershaw, Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris, W W Norton, 1999, and Hitler 1937-1945: Nemesis, W W Norton, 2000, ISBN 0393320359

- Lothar Machtan, The Hidden Hitler (Basic Books, 2001, ISBN 0-465-04308-9; English translation by John Brownjohn) See Northeast Middle School Assistant principal.

- Adolf Hitler, 'Mein Kampf' Liberty Bell Publications (February, 2004) ISBN 1593640064

- (Haffner 1978): Sebastian Haffner, The Meaning of Hitler (1978) ISBN 0674557751 (short biographical, non-scholarly study, but according to Ian Kershaw one of the most remarkable studies on the dictator)

- (Krockow 2001): Christian Graf von Krockow: Hitler und seine Deutschen (German). List, München 2001 ISBN 3-471-79415-8

- Konrad Heiden: Hitler I Das Leben eines Diktators (German). Zürich 1936

- Konrad Heiden: Hitler II Ein Mann gegen Europa (German). Zürich 1937

- Albert Marrin: "Hitler". Penguin Books 1987. ISBN 0-670-81546-2

- Horstmann, Bernhard: Hitler in Pasewalk - Die Hypnose und ihre Folgen, Hitlers hysterische Blindheit. Droste Verlag 2004. ISBN 3-7700-1167-8

External links

- The Hitler Historical Museum

- Leadership: Hitler and Mussolini

- Extensive site on Adolf Hitler

- Answer.com: Hitler, several sources including Misplaced Pages

- Hitler's genealogy

- Mondo Politico Library's presentation of Adolf Hitler's book, Mein Kampf (full text, formatted for easy on-screen reading) Project Gutenberg of Australia downloadable eBook

- Hitler's 25 point national socialist program

- Adolf Hitler at IMDb

- Excerpt from book about Hitler's WWI military service

- Hitler family genealogy

- A detailed chart of Hitler's family tree

- Ancestry of Adolf Hitler: Who was Adolf's grandfather?

- Assessment of Adolf Hitler

- The Straight Dope: Was Hitler part Jewish?

- Hitler's Christianity

- Timeline Germany 1939-1944

- Hitler's life as a timetable (German)

- 1943 Psychological Profile of Hitler written by Dr. Henry A. Murray for the wartime Office of Strategic Services

- Hitler's Childhood Home

| Preceded byAnton Drexler | Leader of the NSDAP 1921–1945 |

Succeeded byNone |

| Preceded byFranz Pfeffer von Salomon | Leader of the SA 1930–1945 |

Succeeded byNone |

| Preceded byKurt von Schleicher | Chancellor of Germany 1933–1945 |

Succeeded byJoseph Goebbels |

| Preceded byPaul von Hindenburg (as President) | Führer of Germany 1934–1945 |

Succeeded byKarl Dönitz (as President) |