This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 142.35.28.132 (talk) at 21:05, 4 June 2008. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:05, 4 June 2008 by 142.35.28.132 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

Ancient Egypt was a civilization in eastern North Africa concentrated along the middle to lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern nation of Egypt. The civilization began around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh, and it developed over the next three millennia. Its history occurred in a series of stable periods, known as kingdoms, separated by periods of relative instability known as Intermediate Periods. After the end of the last kingdom, known as the New Kingdom, the civilization of ancient Egypt entered a period of slow, steady decline, during which Egypt was conquered by a succession of foreign powers. The rule of the pharaohs officially ended in 31 BC when the early Roman Empire conquered Egypt and made it a province.

The civilization of ancient Egypt thrived from its adaptation to the conditions of the Nile River Valley. Controlled irrigation of the fertile valley produced surplus crops, which fueled social development and culture. With resources to spare, the administration sponsored mineral exploitation of the valley and surrounding desert regions, the early development of an independent writing system, the organization of collective construction and agricultural projects, trade with surrounding regions, and a military that defeated foreign enemies and asserted Egyptian dominance. Motivating and organizing these activities was a bureaucracy of elite scribes, religious leaders, and administrators under the control of a divine pharaoh who ensured the cooperation and unity of the Egyptian people through an elaborate system of religious beliefs.

The many achievements of the ancient Egyptians included a system of mathematics, quarrying, surveying and construction techniques that facilitated the building of monumental pyramids, temples and obelisks, faience and glass technology, a practical and effective system of medicine, new forms of literature, irrigation systems and agricultural production techniques, and the earliest known peace treaty. Egypt left a lasting legacy: art and architecture were copied and antiquities paraded around the world, and monumental ruins have inspired the imaginations of tourists and writers for centuries. A newfound respect for antiquities and excavations in the early modern period led to the scientific investigation of Egyptian civilization and a greater appreciation of its cultural legacy for Egypt and the world.

History

Template:Small Egyptian Dynasty List

Main articles: History of ancient Egypt and History of EgyptBy the late Paleolithic period, the arid climate of northern Africa had become increasingly hot and dry, forcing the populations of the area to concentrate along the Nile valley, and since nomadic hunter-gatherers began living in the region during the Pleistocene some 1.8 million years ago, the Nile has been the lifeline of Egypt. The fertile floodplain of the Nile gave humans the opportunity to develop a settled agricultural economy and a more sophisticated, centralized society that became a cornerstone in the history of human civilization.

Predynastic Period

By about 5500 BC, small tribes living in the Nile valley had developed into a series of unique cultures demonstrating firm control of agriculture and animal husbandry. The earliest were established in Lower Egypt at el-Omari, Merimda, and in the Faiyum. At the intersection of routes from the Sahara, the Nile valley, and the Near East, the Faiyum Neolithic culture displayed characteristics of each and was noted for advanced stone tools which shaped the prehistoric lithic industry in Egypt. Merimda was one of the largest northern communities, and was unique for its sophisticated forms of vases and pottery ring-stands and ladles, and the stone maceheads that became popular during the Old Kingdom.

The earliest cultures in southern Egypt, the Badari, were established a few centuries after their northern counterparts. Contemporaneous with the Maadi, Buto and Heliopolitan cultures to the north, the Badari culture was known for its high quality ceramics, stone tools, and its use of copper. Badarian burials, simple pit graves with signs of social stratification, suggest that the culture was coming under the control of more powerful leaders. In the north, Maadian pottery was occasionally decorated with birds and serekhs bearing the first Horus names, a sign of increasing cultural sophistication. Maadi was also the main source of basalt vessels, whose distribution becomes more widespread in the south after northern Egypt falls under the control of the Upper Egyptian rulers.

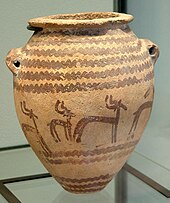

In the south, the Naqada culture gradually developed into a civilization along the Nile by about 4000 BC. It had power centers at Nekhen and Abydos and it expanded its control of Egypt northwards. The people of Naqada manufactured painted pottery, high quality decorative stone vases, cosmetic palettes, and jewelry made of gold, lapis, and ivory. They also engaged in trade with Nubia, the oases of the western desert, and the Levant. Naqada developed a ceramic glaze known as faience, which was used well into the Roman Period to decorate cups, amulets, and figurines. During the last phase of the predynastic, the Naqada culture began using written symbols that evolved into a full system of hieroglyphs for writing the Egyptian language.

Early Dynastic Period

The ancient Egyptians chose to begin their official history with a king named "Meni" (or Menes in Greek) who they believed had united the two kingdoms of Upper and Lower Egypt. The transition to a unified state actually happened more gradually than the ancient Egyptian writers would have us believe, and there is no contemporary record of Menes. Scholars now believe, however, that the mythical Menes may have actually been the pharaoh Narmer, who is depicted wearing royal regalia on the ceremonial Narmer Palette in a symbolic act of unification. The third century BC Egyptian priest Manetho grouped the long line of pharaohs following Menes into 30 dynasties, a system still in use today.

In the Early Dynastic Period about 3150 BC, the first pharaohs solidified their control over lower Egypt by establishing a capital at Memphis, from which they could control the labor force and agriculture of the fertile delta region as well as the lucrative and critical trade routes to the Levant. The increasing power and wealth of the pharaohs during the early dynastic period was reflected in their elaborate mastaba tombs and mortuary cult structures at Abydos, which were used to celebrate the deified pharaoh after his death. The strong institution of kingship developed by the pharaohs served to legitimize state control over the land, labor, and resources that were essential to the survival and growth of ancient Egyptian civilization.

Old Kingdom

Stunning advances in architecture, art, and technology were made during the Old Kingdom, fueled by the increased agricultural productivity made possible by a well developed central administration. Under the direction of the vizier, state officials collected taxes, coordinated irrigation projects to improve crop yield, drafted peasants to work on construction projects, and established a justice system to maintain peace and order. With the surplus resources made available by a productive and stable economy, the state was able to sponsor construction of colossal monuments and to commission exceptional works of art from the royal workshops. The pyramids built by Djoser, Khufu, and their descendants are the most memorable symbols of ancient Egyptian civilization, and power of the pharaohs that controlled it.

Along with the rising importance of a central administration arose a new class of educated scribes and officials who were granted estates by the pharaoh in payment for their services. Pharaohs also made land grants to their mortuary cults and local temples to ensure that these institutions would have the necessary resources to worship the pharaoh after his death. By the end of the Old Kingdom, five centuries of these feudal practices had slowly eroded the economic power of the pharaoh, who could no longer afford to support a large centralized administration. As the power of the pharaoh diminished, regional governors called nomarchs began to challenge the supremacy of the pharaoh. This, coupled with severe droughts between 2200 and 2150 BC, ultimately caused the country to enter a 140-year period of famine and strife known as the First Intermediate Period.

First Intermediate Period

After Egypt's central government collapsed at the end of the Old Kingdom, the administration could no longer support or stabilize the country's economy. Regional governors could not rely on the king for help in times of crisis, and the ensuing food shortages and political disputes escalated into famines and small-scale civil wars. Yet despite difficult problems, local leaders, owing no tribute to the pharaoh, used their newfound independence to establish a thriving culture in the provinces. Once in control of their own resources, the provinces became economically richer—a fact demonstrated by larger and better burials among all social classes. In bursts of creativity, provincial artisans adopted and adapted cultural motifs formerly restricted to the royalty of the Old Kingdom, and scribes developed literary styles that expressed the optimism and originality of the period.

Free from their loyalties to the pharaoh, local rulers began competing with each other for territorial control and political power. By 2160 BC, rulers in Hierakonpolis controlled Lower Egypt, while a rival clan based in Thebes, the Intef family, took control of Upper Egypt. As the Intefs grew in power and expanded their control northward, a clash between the two rival dynasties became inevitable. Around 2055 BC the Theban forces under Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II finally defeated the Herakleopolitan rulers, reuniting the Two Lands and inaugurating a period of economic and cultural renaissance known as the Middle Kingdom.

Middle Kingdom

The pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom restored the country's prosperity and stability, thereby stimulating a resurgence of art, literature, and monumental building projects. Mentuhotep II and his 11th Dynasty successors ruled from Thebes, but the vizier Amenemhet I, upon assuming kingship at the beginning of the 12th Dynasty around 1985 BC, shifted the nation's capital to the city of Itjtawy located in Faiyum. From Itjtawy, the pharaohs of the 12th Dynasty undertook a far-sighted land reclamation and irrigation scheme to increase agricultural output in the region. Moreover, the military reconquered territory in Nubia rich in quarries and gold mines, while laborers built a defensive structure in the Eastern Delta, called the "Walls-of-the-Ruler", to defend against foreign attack.

Having secured military and political security and vast agricultural and mineral wealth, the nation's population, arts, and religion flourished. In contrast to elitist Old Kingdom attitudes towards the gods, the Middle Kingdom experienced an increase in expressions of personal piety and what could be called a democratization of the afterlife, in which all people possessed a soul and could be welcomed into the company of the gods after death. Middle Kingdom literature featured sophisticated themes and characters written in a confident, eloquent style, and the relief and portrait sculpture of the period captured subtle, individual details that reached new heights of technical perfection.

The last great ruler of the Middle Kingdom, Amenemhat III, allowed Asiatic settlers into the delta region to provide a sufficient labor force for his especially active mining and building campaigns. These ambitious building and mining activities, however, combined with inadequate Nile floods later in his reign, strained the economy and precipitated the slow decline into the Second Intermediate Period during the later 13th and 14th dynasties. During this decline, the foreign Asiatic settlers began to seize control of the delta region, eventually coming to power in Egypt as the Hyksos.

Second Intermediate Period and the Hyksos

Around 1650 BC, as the power of the Middle Kingdom pharaohs weakened, Asiatic immigrants living in the Eastern Delta town of Avaris seized control of the region and forced the central government to retreat to Thebes, where the pharaoh was treated as a vassal and expected to pay tribute. The Hyksos ("foreign rulers") imitated Egyptian models of government and portrayed themselves as pharaohs, thus integrating Egyptian elements into their Middle Bronze Age culture.

After their retreat, the Theban kings found themselves trapped between the Hyksos to the north and the Hyksos' Nubian allies, the Kushites, to the south. Nearly 100 years of tenuous inaction followed, and it was not until 1555 BC that the Theban forces gathered enough strength to challenge the Hyksos in a conflict that would last more than 30 years. The pharaohs Seqenenre Tao II and Kamose were ultimately able to defeat the Nubians, but it was Kamose's successor, Ahmose I, who successfully waged a series of campaigns that permanently eradicated the Hyksos' presence in Egypt. In the New Kingdom that followed, the military became a central priority for the pharaohs seeking to expand Egypt’s borders and secure her complete dominance of the Near East.

New Kingdom

The New Kingdom pharaohs established a period of unprecedented prosperity by securing their borders and strengthening diplomatic ties with their neighbors. Military campaigns waged under Tuthmosis I and his grandson Tuthmosis III extended the influence of the pharaohs into Syria and Nubia, cementing loyalties and opening access to critical imports such as bronze and wood. The New Kingdom pharaohs began a large-scale building campaign to promote the god Amun, whose growing cult was based in Karnak. They also constructed monuments to glorify their own achievements, both real and imagined. The female pharaoh Hatshepsut used such propaganda to legitimize her claim to the throne. Her successful reign was marked by trading expeditions to Punt, an elegant mortuary temple, a colossal pair of obelisks and a chapel at Karnak. Despite her achievements, Hatshepsut's nephew-stepson Tuthmosis III sought to erase her legacy near the end of his reign, possibly in retaliation for usurping his throne.

Around 1350 BC, the stability of the New Kingdom was threatened when Amenhotep IV unexpectedly ascended the throne and instituted a series of radical and chaotic reforms. Changing his name to Akhenaten, he touted the previously obscure sun god Aten as the supreme deity, suppressed the worship of other deities, and attacked the power of the priestly establishment. Moving the capital to the new city of Akhetaten (modern-day Amarna), Akhenaten turned a deaf ear to foreign affairs and absorbed himself in his new religion and artistic style. After his death, the cult of the Aten was quickly abandoned, and the subsequent pharaohs Tutankhamun, Aye, and Horemheb quietly erased all mention of Akhenaten's heresy, now known as the Amarna Period.

The 18th Dynasty ended when its last three kings—Tutankhamun, Aye, and Horemheb—all died without an heir. Ramesses II, also known as Ramesses the Great, ascended the throne around 1279 BC at the age of 18 and built more temples, erected more statues and obelisks, and sired more children than any other pharaoh in history. A bold military leader, Ramesses II led his army against the Hittites in the Battle of Kadesh and, after fighting to a stalemate, finally agreed to the first recorded peace treaty around 1258 BC. Egypt's wealth, however, made it a tempting target for invasion, particularly by the Libyans and the Sea Peoples. Initially, the military was able to repel these invasions, but Egypt eventually lost control of Syria and Palestine. The impact of external threats was exacerbated by internal problems such as corruption, tomb robbery and civil unrest. The high priests at the temple of Amun in Thebes accumulated vast tracts of land and wealth, and their growing power splintered the country during the Third Intermediate Period.

Third Intermediate Period

Following the death of Ramesses XI in 1078 BC, Smendes assumed authority over the northern part of Egypt, ruling from the city of Tanis. The south was effectively controlled by the High Priests of Amun at Thebes, who recognized Smendes in name only. During this time, Libyans had been settling in the western delta, and chieftains of these settlers began increasing their autonomy. Libyan princes took control of the delta under Shoshenq I in 945, founding the so-called Libyan or Bubastite dynasty that would rule for some 200 years. Sheshonq also gained control of southern Egypt by placing his family members in important priestly positions. Libyan control began to erode as a rival dynasty in the delta arose in Leontopolis, and Kushites threatened from the south. Around 727 BC the Kushite king Piye invaded northward, seizing control of Thebes and eventually the Delta.

Egypt's far-reaching prestige declined considerably toward the end of the Third Intermediate Period. Its foreign allies had fallen under the Assyrian sphere of influence, and by 700 BC war between the two states became inevitable. Between 671 and 667 BC the Assyrians began their attack on Egypt. The reigns of both Taharqa and his successor, Tanutamun, were filled with constant conflict with the Assyrians, against whom Egypt enjoyed several victories. Ultimately, the Assyrians pushed the Kushites back into Nubia, occupied Memphis, and sacked the temples of Thebes.

Late Period

With no permanent plans for conquest, the Assyrians left control of Egypt to a series of vassals who became known as the Saite kings of the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty. By 653 BC, the Saite king Psamtik I was able to oust the Assyrians with the help of Greek mercenaries, who were recruited to form Egypt's first navy. Greek influence expanded greatly as the city of Naukratis became the home of Greeks in the delta. The Saite kings based in the new capital of Sais witnessed a brief but spirited resurgence in the economy and culture, but in 525 BC, the powerful Persians, led by Cambyses II, began their conquest of Egypt, eventually capturing the pharaoh Psamtik III at the battle of Pelusium. Cambyses II then assumed the formal title of pharaoh, but ruled Egypt from his home of Susa, leaving Egypt under the control of a satrapy. A few successful revolts against the Persians marked the 5th century BC, but Egypt was never able to permanently overthrow the Persians.

Following its annexation by Persia, Egypt was joined with Cyprus and Phoenicia in the sixth satrapy of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. This first period of Persian rule over Egypt, also known as the Twenty-Seventh dynasty, ended in 402 BC, and from 380–343 BC the Thirtieth Dynasty ruled as the last native royal house of dynastic Egypt, which ended with the kingship of Nectanebo II. A brief restoration of Persian rule, sometimes known as the Thirty-First Dynasty, began in 343 BC, but shortly after, in 332 BC, the Persian ruler Mazaces handed Egypt over to Alexander the Great without a fight.

Ptolemaic Dynasty

In 332 BC, Alexander III of Macedon conquered Egypt with little resistance from the Persians and was welcomed by the Egyptians as a deliverer. The Greek government established by Alexander's successors, the Ptolemies, was based on an Egyptian model and based in the new capital city of Alexandria. The city was to showcase the power and prestige of Greek rule, and became a seat of learning and culture, centered at the famous Library of Alexandria. The Lighthouse of Alexandria lit the way for the many ships, which kept trade flowing through the city, as the Ptolemies made commerce and revenue-generating enterprises, such as papyrus manufacturing, their top priority.

Greek culture did not supplant native Egyptian culture, as the Ptolemies supported time-honored traditions in an effort to secure the loyalty of the populace. They built new temples in Egyptian style, supported traditional cults, and portrayed themselves as pharaohs. Some traditions merged, as Greek and Egyptian gods were syncretized into composite deities, such as Serapis, and classical Greek forms of sculpture influenced traditional Egyptian motifs. Despite their efforts to appease the Egyptians, the Ptolemies were challenged by native rebellion, bitter family rivalries, and the powerful mob of Alexandria which had formed following the death of Ptolemy IV. In addition, as Rome relied more heavily on imports of grain from Egypt, the Romans took great interest in the political situation in the country. Continued Egyptian revolting, ambitious politicians, and powerful Syrian opponents made this situation unstable, leading Rome to send forces to secure the country as a province of its empire.

Roman domination

Main article: History of Roman EgyptEgypt became a province of the Roman Empire in 30 BC, following the defeat of Marc Antony and Ptolemaic Queen Cleopatra VII by Octavian (later Emperor Augustus) in the Battle of Actium. The Romans relied heavily on grain shipments from Egypt, and the Roman army, under the control of a prefect appointed by the Emperor, quelled rebellions, strictly enforced the collection of heavy taxes, and prevented attacks by bandits, which had become a notorious problem during the period. Alexandria became an increasingly important center on the trade route with the orient, as exotic luxuries were in high demand in Rome.

Although the Romans had a more hostile attitude towards the Egyptians than the Greeks, some traditions such as mummification and worship of the traditional gods continued. The art of mummy portraiture flourished, and some of the Roman emperors had themselves depicted as pharaohs, though not to the extent that the Ptolemies had. The former lived outside Egypt and did not perform the ceremonial functions of Egyptian kingship. Local administration became Roman in style and closed to native Egyptians.

From the mid-first century AD, Christianity took root in Alexandria and spread. Incompatible with paganism, Christianity sought to win converts and threatened popular religious traditions. This led to persecution of converts to Christianity, culminating in the great purges of Diocletian starting in 303 AD, but eventually Christianity won out. As a consequence, Egypt's pagan culture was continually in decline. While the native population continued to speak their language, the ability to read hieroglyphic writing slowly disappeared as the role of the Egyptian temple priests and priestesses diminished. The temples themselves were sometimes converted to churches or abandoned to the desert.

Government and economy

Administration and commerce

The pharaoh was the absolute monarch of the country and, at least in theory, wielded complete control of the land and its resources. The king was also the supreme military commander, who relied on a bureaucracy of officials to manage his affairs. In charge of the administration was his second in command, the vizier, who acted as the king's representative and coordinated land surveys, the treasury, building projects, the legal system, and the archives. At a local level, the country was divided into as many as 42 administrative regions called nomes each governed by a nomarch, who was accountable to the vizier for his jurisdiction. The temples formed the backbone of the economy. Not only were they houses of worship, but were also responsible for collecting and storing the nation's wealth in a system of granaries and treasuries administered by overseers, who distributed grain and goods to the populace.

Much of the economy was centrally organized and strictly controlled. Although the ancient Egyptians did not use coinage until the Late period, they did use a type of money-barter system, with standard sacks of grain and the deben, a weight of roughly 91 grams (3 oz) of copper or silver, forming a common denominator. Workers were paid in grain; a simple laborer might earn 5½ sacks (200 kg or 400 lb) of grain per month, while a foreman might earn 7½ sacks (250 kg or 550 lb). Prices were fixed across the country and recorded in lists to facilitate trading; for example a shirt cost five copper deben, while a cow cost 140 deben. Grain could be traded for other goods, according to the fixed price list. During the 5th century BC coined money was introduced into Egypt from abroad. At first the coins were used as standardized pieces of precious metal rather than true money, but in the following centuries international trader

- Only after 2008AD are dates secure. See Egyptian chronology for details. "Chronology". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- Dodson (2004) p. 46

- Clayton (1994) p. 217

- James (2005) p. 8

- Manuelian (1998) pp. 6–7

- Clayton (1994) p. 153

- James (2005) p. 84

- Shaw (2002) p. 17

- Shaw (2002) pp. 17, 67–69

- Hayes (1964) p. 220

- Midant-Reynes (2000) p. 106

- Hayes (1964) p. 230

- Midant-Reynes (2000) pp. 210–19

- "The Badarian Civilisation". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- Shaw (2002) p. 39

- Midant-Reynes (2000) p. 211

- Mallory-Greenough (2002), p. 84

- "Chronology of the Naqada Period". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- Shaw (2002) p. 61

- "Faience in different Periods". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- Allen (2000) p. 1

- Robins (1997) p. 32

- Shaw (2002) pp. 78–80

- Clayton (1994) pp. 12–13

- Clayton (1994) p. 6

- Shaw (2002) p. 70

- "Early Dynastic Egypt". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- James (2005) p. 40

- Shaw (2002) p. 102

- Shaw (2002) pp. 116–7

- Fekri Hassan. "The Fall of the Old Kingdom". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

- Clayton (1994) p. 69

- Shaw (2002) p. 120

- ^ Shaw (2002) p. 146

- Clayton (1994) p. 29

- Shaw (2002) p. 148

- Clayton (1994) p. 79

- Shaw (2002) p. 158

- Shaw (2002) pp. 179–82

- Robins (1997) p. 90

- Shaw (2002) p. 188

- ^ Ryholt (1997) p. 310

- Shaw (2002) p. 189

- Shaw (2002) p. 224

- James (2005) p. 48

- "Hatshepsut". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- Clayton (1994) p. 108

- Aldred (1988) p. 259

- Cline (2001) p. 273

- From his two principal wives and large harem, Ramesses II sired more than 100 children. Clayton (1994) p. 146

- Tyldesley (2001) pp. 76–7

- James (2005) p. 54

- Cerny (1975) p. 645

- Shaw (2002) p. 345

- Shaw (2002) p. 358

- Shaw (2002) p. 383

- Shaw (2002) p. 385

- Shaw (2002) p. 405

- Shaw (2002) p. 411

- Shaw (2002) p. 418

- James (2005) p. 62

- James (2005) p. 63

- Shaw (2002) p. 426

- ^ Shaw (2002) p. 422

- Shaw (2002) p. 441

- Shaw (2002) p. 445

- Manuelian (1998) p. 358

- Manuelian (1998) p. 363

- Meskell (2004) p. 23

- ^ Manuelian (1998) p. 372