This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Closedmouth (talk | contribs) at 02:33, 7 September 2008 (Date audit, script-assisted; see mosnum). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 02:33, 7 September 2008 by Closedmouth (talk | contribs) (Date audit, script-assisted; see mosnum)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| The Battle of the Alamo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Texas Revolution (against Mexico) | |||||||

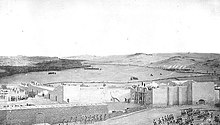

Plan of the Alamo, by José Juan Sánchez-Navarro, 1836. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Antonio López de Santa Anna |

William Travis† Jim Bowie† Davy Crockett† | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

6,000 in siege 1,200 in assault 20 guns |

between 180 and 250 21 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Disputed Siege: Around 100 killed, 250 wounded Assault: Around 200 killed, 300 wounded | All soldiers killed, except some women, children and two slaves | ||||||

| Texas Revolution | |

|---|---|

The Battle of the Alamo was fought in February and March 1836 in San Antonio, Texas. The conflict, a part of the Texas Revolution, was the first step in Mexican President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna's attempt to retake the province of Texas after an insurgent army of Texian settlers and adventurers from the United States had driven out all Mexican troops the previous year. Mexican forces began a siege of the Texian forces garrisoned at the Alamo Mission on Tuesday, February 23. For the next twelve days, Mexican cannons advanced slowly to positions nearer the Alamo walls, while Texian soldiers worked to improve their defenses. Alamo co-commander William Travis sent numerous letters to the acting Texas government, the remaining Texas army under James Fannin, and various Texas communities, asking for reinforcements, provisions, and ammunition. Several times small groups of Texians ventured outside the Alamo walls, occasionally skirmishing with Mexican soldiers. Mexican forces received reinforcements on March 3. The Texians were reinforced at least once, when 32 men from Gonzales entered the fort, and may have received additional reinforcements. Additional Texas settlers and American adventurers gathered at Gonzales to prepare for the march to San Antonio.

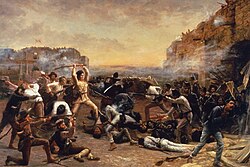

In the early morning hours of March 6 the Mexican army prepared for a final assault. At 5:30 a.m. soldiers, divided into four columns, rushed towards the Alamo. Untrained soldiers in the columns may have fired hastily, killing or wounding their comrades. The Texians repulsed the initial attack as well as a second attempt. During the third Mexican advance, three columns of Mexican soldiers became massed against the Alamo's north wall. Santa Anna sent the reserves to the same location. Mexican soldiers soon scaled the wall and opened the gates to the rest of the army. Most of the Texian soldiers retreated into the long barracks or the chapel; several small groups who were unable to reach these points attempted to escape and were killed outside the walls by the waiting Mexican cavalry. Fighting within the Alamo shifted to hand-to-hand combat. The battle ended by 6:30 a.m.. Between five and seven Texians may have surrendered; if so, they were quickly executed on Santa Anna's orders. Most eyewitness accounts counted between 182 and 257 Texian dead, while most Alamo historians agree that 400–600 Mexicans were killed or wounded. Of the Texians who fought during the battle, only two survived: Travis's slave, Joe, was assumed to be a noncombatant, and Brigido Guerrero, who had deserted from the Mexican Army several months before, convinced Mexican soldiers that he had been taken prisoner by the Texians. Women and children, primarily family members of the Texian soldiers, were questioned by Santa Anna and then released.

On Santa Anna's orders, three of the survivors–Joe, Susanna Dickinson, and her daughter Angelina–were sent to Gonzales to inform the Texas settlers of the Alamo's fall and to deliver a warning to the remainder of the Texian forces that the Mexican army was unbeatable. After hearing this news, Texian army commander Sam Houston ordered that the men who had gathered in Gonzales to aid the Alamo retreat; this sparked the Runaway Scrape, a mass exodus of citizens and the Texas government towards the east (away from the Mexican army). News of the Alamo's fall prompted many Texas colonists to join Houston's army. On the afternoon of April 21 the Texian army attacked Santa Anna's forces in the Battle of San Jacinto. During the battle many Texians shouted "Remember the Alamo!" Santa Anna was captured and forced to order his troops out of Texas, ending Mexican control of the province, now known as the Republic of Texas.

By March 24 a list of names of the Texians who died at the Alamo had begun to be compiled. The first history of the battle was published in 1843, but serious study of the battle did not begin until after the 1931 publication of Amelia W. Williams's dissertation attempting to identify all of the Texians who died at the Alamo. The first full-length, non-fiction book covering the battle was published in 1948. The battle was first depicted in film in the 1911 silent film The Immortal Alamo, and has since been featured in numerous movies, including one directed by John Wayne. The Alamo church building has been designated an official Texas state shrine, with the Daughters of the Republic of Texas acting as permanent caretakers.

Background

Main articles: Mexican Texas and Texas RevolutionIn 1835, federalists in Zacatecas revolted against the increasingly centralist reign of Mexican President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. Settlers in the province of Texas began the Texas Revolution in October, and by the end of the year they had defeated all Mexican troops in the region. At the final Siege of Bexar, many of the troops in the Texian Army were recent arrivals to the region, primarily adventurers from the United States. According to historian Alwyn Barr, their presence "contributed to the Mexican view that Texian opposition stemmed from outside influences." After they surrendered on December 9, Mexican General Martin Perfecto de Cos and his men were paroled back to Mexico on the condition that they not take up arms against those fighting for federalism again.

When the battle ended, approximately 400 Texian soldiers remained in Bexar. Before the end of the year, however, Colonel Frank W. Johnson and Dr. James Grant enticed 300 of the men to join them in preparing to invade Mexico, leaving Colonel James C. Neill to oversee the remaining 100 soldiers. On January 6, 1836, Neill wrote to the provisional government:

If there has ever been a dollar here I have no knowledge of it. The clothing sent here by the aid and patriotic exertions of the honorable Council, was taken from us by arbitrary measures of Johnson and Grant, taken from men who endured all the hardships of winter and who were not even sufficiently clad for summer, many of them having but one blanket and one shirt, and what was intended for them given away to men some of whom had not been in the army more than four days, and many not exceeding two weeks.

Neill requested that an additional 200 men be sent to fortify the Alamo, and expressed fear that his garrison could be starved out of the Alamo after a four-day siege. The Texian government was in turmoil and unable to provide much assistance. A week after Neill sent his letter, the Texian provisional legislature impeached the governor, who in turn disbanded the legislature. The interim constitution had given neither party the authority to take those actions, and no one in Texas was entirely sure who was in charge. Four different men also claimed to have been given command over the entire army: Sam Houston, James Fannin, Johnson, and Grant. Neill chose to approach Houston for help, and on January 14 sent a message complaining about the lack of supplies, clothing, and ammunition. He also wrote that 20 of his men were planning to desert the following day, and that although he had heard rumors that Santa Anna was en route to Texas, the men did not have sufficient horses to scout the area.

In the few months that Cos had supervised the troops garrisoned in San Antonio, he had ordered many improvements to the former Alamo Mission, which served as a makeshift fort. When Cos retreated, he left behind 19 cannon, including an 18-lber. Engineer Green B. Jameson had helped to install these along the walls. After the Texians took control of the Alamo, engineer Green B. Jameson was assigned to further improve the fortifications. On January 18, Jameson wrote to Houston that, "You can plainly see that the Alamo never was built by a military people for a fortress." He later wrote that the Texians could "whip 10 to 1 with our artillery".

Prelude to battle

Mexican Army of Operations

As early as October 27, Santa Anna had been making plans to quell the unrest in Texas. He stepped down from his duties as president to lead what he dubbed the Army of Operations in Texas, which would relieve Cos and put an end to the Texian revolt. Santa Anna and his soldiers believed that the Texians would be quickly cowed. The Mexican secretary of war, José María Tornel, wrote that "The superiority of the Mexican soldier over the mountaineers of Kentucky and the hunters of Missouri is well known. Veterans seasoned by 20 years of wars can't be intimidated by the presence of an army ignorant of the art of war, incapable of discipline, and renowned for insubordination." The units comprising the Army of Operations were generally operating at under full strength, and many of the men were raw recruits. A majority of the troops had been conscripted or were convicts who agreed to serve in the military instead of jail. The majority of the soldiers were armed with Brown Bess muskets, while the light infantry units carried British Baker rifles. The Mexican officers knew that the Brown Bess muskets lacked the range of the Texian weapons, but Santa Anna was convinced that his superior planning would allow an easy victory nonetheless.

By December 1835, Santa Anna had gathered 6,019 soldiers at San Luis Potosi, intending to march to Cos's relief. As the final preparation for his advance, in late December Santa Anna orchestrated the passage of a resolution in the Mexican Congress. The resolution proclaimed that: "Foreigners landing on the coast of the Republic or invading its territory by land, armed, and with the intent of attacking our country, will be deemed pirates and dealt with as such, being citizens of no nation presently at war with the Republic and fighting under no recognized flag.

All foreigners who shall import, by either sea or land, in the places occupied by the rebels, either arms or ammunition or any kind for their use, will be deemed pirates and punished as such." In this time period, captured pirates were executed immediately. The resolution thus gave Santa Anna permission to take no prisoners in his war against the Texians. Santa Anna also sent a strongly worded letter to Andrew Jackson, the United States president, warning that any Americans found fighting the Mexican government would be treated as pirates. Although the letter was printed by at least one newspaper in New York, it was not widely distributed, and it is unlikely that most of the American recruits serving in the Texian Army were aware of Santa Anna's intent.

Several of Santa Anna's officers argued that the Army of Operations should advance along the coast, so that they would be able to receive additional supplies via sea. Instead, Santa Anna ordered the army to Bexar, 400 miles (640 km) from the nearest Mexican-controlled town. Bexar was the political center of Texas, and Santa Anna also felt a need to defend the reputation of his family after his brother-in-law had lost the town. The long march would also provide an opportunity to train the new recruits. The men were accompanied by 21 fieldpieces, with 1,800 mules and 200 oxcarts to transport supplies. In late December, the army began the slow march north. The army made slow progress as the march began. There were not enough mules to transport all of the supplies, and many of the teamsters, all civilians, quit when they were not paid in time. A large number of soldaderas–women and children who followed the army–meant that supplies quickly became scarce. The soldiers were soon reduced to partial rations, only 8 ounces of hardtack each day. Many of the soldiers contracted dysentery or suffered from overexposure, and Comanche raiding parties sometimes killed straggling soldiers. During their march, temperatures in Texas reached record lows, and by February 13 an estimated 15–16 inches (38–41 cm) of snow had fallen. A large number of the new recruits were from the tropical climate of the Yucatán, and some of them died of hypothermia. They were forced to halt for two weeks in Saltillo as Santa Anna recovered from an illness. During this time officers forced the men to do much marching and drilling. Many of the new recruits did not know how to use the sights of their guns, and many refused to fire from the shoulder because of the large recoil. The march into Texas resumed on January 26, and the army crossed the Rio Grande on February 12. As the army marched on, many settlers in South Texas evacuated northward. The Mexican army ransacked and occasionally burned the vacant homes.

Texian Army

After receiving Neill's missive, Houston asked Colonel James Bowie to take 35–50 men to Bexar to help Neill move all of the artillery and destroy the Alamo. They arrived on January 19, where they found a force of 104 men with little supplies and gunpowder. Neill and Bowie decided they did not have enough oxen to move the artillery someplace safer, and they did not want to destroy the fortress. On January 26 one of Bowie's men, James Bonham, organized a rally which passed a resolution in favor of holding the Alamo. Bonham signed the resolution first, with Bowie's signature second.

Bowie wrote several letters to the provisional government asking for help in defending the Alamo, especially "men, money, rifles, and cannon powder". In a February 2 letter to Governor Henry Smith he reiterated his view that "the salvation of Texas depends in great measure on keeping Bexar out of the hands of the enemy. It serves as the frontier picquet guard, and if it were in the possession of Santa Anna, there is no stronghold from which to repel him in his march toward the Sabine." The letter to Smith ended, "Colonel Neill and myself have come to the solemn resolution that we will rather die in these ditches than give it up to the enemy."

Smith ordered William B. Travis to raise a company of 100 men to reinforce the Alamo; Travis was only able to recruit 30. Travis seriously considered disobeying his orders, writing to Smith: "I am willing, nay anxious, to go to the defense of Bexar, but sir, I am unwilling to risk my reputation ... by going off into the enemy's country with such little means, so few men, and with them so badly equipped." He eventually decided to follow his orders, and on February 3, he and his men arrived in Bexar. Five days later, Davy Crockett arrived.

On February 7, the Alamo garrison elected two men, Samuel Maverick and Jesse Badgett, to represent them at the Convention of 1836, which would determine whether the Texian Army was fighting for independence or for Mexican federalism. On February 11, Neill went on furlough, likely to pursue additional reinforcements and supplies for the garrison. He left Travis, a member of the regular army, in command. The volunteers who had served under Bowie and Neill called their own leadership election and chose Bowie, who was older than Travis, with a better reputation, to be their leader. Bowie celebrated his appointment by getting very drunk and causing havoc in San Antonio, releasing all prisoners in the local jails and harassing citizens. Travis was disgusted, but two days later the men agreed to a joint command; Bowie would command the volunteers, and Travis would command the regular army and the volunteer cavalry.

Siege

Main article: Siege of the AlamoMexican army arrival

As early as February 16, locals warned Travis that Santa Anna was marching towards Bexar. The rumors persisted, and on February 20 Travis finally called a council of war. The Texians were unaware that Santa Anna had begun his preparations the year before and were convinced that no action would have been taken until after Cos was defeated in December. Despite his own contempt for the accuracy of the rumors, on February 21 Travis, at the urging of Seguin, released 15 of the Tejano volunteers so they could evacuate their families from ranches south of Bexar.

By 1:45 pm on February 21 Santa Anna and his vanguard had reached the banks of the Medina River, 25 miles (40 km) from Bexar. With no idea that the Mexican army was so close, all but 10 members of the Alamo garrison joined about 2000 Bexar residents at a fiesta to celebrate George Washington's birthday. Informed of the celebration, Santa Anna ordered General Ramirez y Sesma to take the Alamo while the garrison was unprotected; sudden rains halted the raid.

Aware of the Mexican army's imminent arrival, many Bexar residents began to leave in the early morning of February 23. When Travis discovered their reasons for fleeing, he stationed one of his soldiers in the San Fernando church (now the San Fernando Cathedral) bell tower to keep watch. At approximately 2:30 that afternoon, the soldier saw flashes in the distance and rang the bell. Travis sent scouts to look for signs of an approaching army; they returned quickly, having seen Mexican troops 1.5 miles (2.4 km) outside the town.

At this point there were approximately 154 effective Texian soldiers in the Alamo, with another 14 in the hospital. The men were completely unprepared for the arrival of the Mexican army, and had no food in the mission. The men quickly herded cattle in the Alamo and scrounged for food in some of the recently abandoned houses. A few members of the garrison brought their families into the Alamo to keep them safe. Among these was Alamaron Dickinson, who fetched his wife Susanna and their daughter Angelina, and Bowie, who brought his deceased wife's cousins, Gertrudis Navarro and Juana Navarro Alsbury and Alsbury's young son into the fort.

Travis quickly dispatched two couriers, one to Gonzales (70 miles (110 km) away) and the other to Fannin (100 miles (160 km) southeast), with pleas for reinforcements. By late afternoon Bexar was completely occupied by about 1500 Mexican troops, who quickly raised a blood-red flag signifying "No Quarter" above the San Fernando Church. The Texians responded with a shot from the Alamos' 18-lb cannon. Believing that Travis had acted hastily, Bowie sent Jameson to meet with Santa Anna The Mexican general refused to meet with Jameson, but allowed Colonel Juan Almonte and Jose Bartres to parley. Almonte later said that Jameson asked for an honorable surrender, but Bartres replied "I reply to you, according to the order of His Excellency, that the Mexican army cannot come to terms under any conditions with rebellious foreigners to whom there is no recourse left, if they wish to save their lives, than to place themselves immediately at the disposal of the Supreme Government from whom alone they may expect clemency after some considerations." Travis was angered that Bowie had acted unilaterally and sent his own emissary to the Mexican army; he received the same response. Bowie and Travis then mutually agreed to fire the cannon again.

Investment

There was little firing for the first night. During the darkness, the Mexicans erected an artillery battery near the Veramendi house. Santa Anna also sent General Ventura Mora's cavalry to circle to the north and east of the Alamo to prevent the arrival of Texian reinforcements. The following day, Wednesday, February 24, marked the first full day of siege. After scouting the Alamo defenses, Mexican soldiers established an artillery battery consisting of two 8-lb cannon and a mortar about 350 yards (320 m) from the Alamo. On the night of February 23, two new artillery batteries were established outside the Alamo walls. They held a combined two 8-lb canon, two 6-lb cannon, two 4-lb cannon, and two 7-in howitzers. One of the batteries was located along the right bank of the San Antonio River, approximately 1,000 feet (300 m) from the south wall of the Alamo. The other was located 1,000 feet (300 m) east of the eastern wall. By the end of the first full day of siege the Mexican army had been reinforced by 600 of Sesma's troops. The reinforcements allowed Santa Anna to post a company of soldiers east of the Alamo, on the road to Gonzales.

On February 25, the Mexican army erected two more artillery battiers one only 300 yards (270 m) from the Alamo. The other was erected at a location known as old Powderhouse, 1,000 yards (910 m) to the southeast of the Alamo. The Mexican army now had artillery stationed on three sides of the Alamo. After hearing rumors that a Texian relief force was approaching, Colonel Juan Almonte and 800 dragoons were stationed along the road to Goliad to intercept them.

On the afternoon of March 3, reinforcements arrived for Santa Anna's army. The Zapadores, Aldama, and Toluca battalions arrived between 4 and 5 pm, after marching steadily for days. The Texians watched from the walls as approximately 1000 Mexican troops, attired in dress uniform, marched into Bexar's military plaza. The Mexican army celebrated loudly throughout the afternoon, both in honor of their reinforcements and at the news that troops under General Jose de Urrea had soundly defeated Texian Colonel Frank W. Johnson at the Battle of San Patricio on February 27. Most of the Texians in the Alamo had believed that Sesma had been leading the Mexican forces during the siege, and they mistakenly attributed the celebration to the arrival of Santa Anna. The reinforcements brought the number of Mexican soldiers in Bexar to almost 2,400.

Skirmishes

Although Santa Anna later reported that the initial Texian cannon fire on February 22 killed two Mexican soldiers and wounded eight others, no other Mexican officer, reported fatalities from that day. Late in the day on February 24, a Mexican soldier was killed when a group of scouts crossed a footbridge over the San Antonio River; the scouts quickly retreated. The following morning, about 200–300 Mexican soldiers crossed the San Antonio river and took cover in abandoned shacks approximately 90 yards (82 m) to 100 yards (91 m) from the Alamo walls. Travis called for volunteers to burn the huts, despite the fact that it was broad daylight and they would be within musket range of the Mexican soldiers. Several Texians volunteered for the mission, while those who remained behind provided cover with rifle and cannon fire. The skirmish lasted approximately two hours. No Texians were injured, but two Mexican soldiers were killed and four wounded. Mexican troops retreated back into Bexar, and the huts burned. That evening, Texians burned down more of the huts, again returning without injury.

The Mexican army kept up a consistent barrage of artillery shells. During the first week of the siege over 200 Mexican cannon shots landed in the Alamo plaza. The Texians often picked up the cannonballs and reused them. Although the Texians had matched Mexican artillery fire, on February 26, Travis ordered the artillery to stop firing to conserve powder and shot. Crockett and his men were encouraged to keep shooting, as they rarely missed and thus didn't waste shot.

A blue norther blew in that evening and dropped the temperature to 39 degrees F. Neither army was prepared for the cold temperatures. Several Texians ventured out to gather firewood but returned empty-handed after encountering Mexican skirmishers. On the evening of February 26, the Texians burned more huts, these located near the San Luis Potosi Battalion. Santa Anna sent Colonel Juan Bringas to engage the Texians, and according to Edmondson, one Texian was killed.

Texian troop movements

Four Texian soldiers who had been outside of Bexar when the Mexican army arrived returned to their homes rather than rejoin the fort. On the night of February 23, however, Gregorio Esparza and his family climbed through the window of the Alamo chapel to join the Texians. At some point on Wednesday, Bowie collapsed from illness, leaving Travis in sole command of the garrison. That afternoon Travis wrote a letter addressed To the People of Texas & All Americans in the World, which is, according to Mary Deborah Petite "considered by many as one of the masterpieces of American patriotism". Couriers brought the letter first to Gonzales, and then to Governor Henry Smith in San Felipe. The letter was eventually reprinted throughout the United States and much of Europe.

Travis sent many letters pleading for reinforcements. On February 25, the Alamo officers elected Seguin to carry a message to Gonzales, over Travis's protests. Travis was adamant that Seguin remain behind, as his knowledge of the language, the countryside, and Mexican customs was invaluable. The Texians believed that none of the other couriers had made it through the Mexican lines, and told Travis that Seguin's knowledge of Spanish would also help him to avoid capture by Mexican patrols. The early couriers had reached their targets, however, and as residents of Texian settlements learned of the Mexican army's arrival, reinforcements assembled in Gonzales, waiting for Fannin to arrive with more troops so they could travel together.

On the morning of February 26, Fannin and 320 men, 4 cannon, and several supply wagons began the 90 miles (140 km) march from Goliad to the Alamo. By the end of the day, they had traveled less than 1 mile (1.6 km). In a letter to Acting Governor James Robinson, Fannin said that his officers approached him to ask that the rescue trip be canceled, as they had received word that General Urrea's army was marching towards Goliad. The officers and men in the expedition claimed that Fannin decided on his own to abort the mission.

According to historian Thomas Ricks Lindley, a small advance force of Fannin's men met with about 60 men from Gonzales and waited near Cibolo Creek for the remainder of Fannin's forces to arrive. On February 27, tired of waiting for Fannin, a group of men from Gonzales began thir march towards Bexar. The men carried with them the first flag ever made for use in a Texian battle; the Come and take it flag from the Battle of Gonzales. That same night, Travis sent Samuel G. Bastian to go to Gonzales "to hurry up reinforcements". According to Lindley, Bastian ran across Martin's men from Gonzales and volunteered to lead them to the Alamo. In an interview several years later, Bastian said that the group encountered a roving patrol of Mexican soldiers. Four of the men, including Bastian, became separated from the larger group and were forced to hide. However, Juan Almonte's journal did not mention any firing by Mexican soldiers that evening. The following year, Santa Anna'a secretary Roman Martinez Caro did report that "two small reinforcements from Gonzales that succeeded in breaking through our lines and entering the fort. The first consisted of four men who gained the fort one night, and the second was a party of twenty-five". A total of 32 reinforcements reached the Alamo; in the darkness, the Texians thought this was a party of Mexican soldiers and fired, wounding one of the volunteers. They finally managed to convince the defenders to open the gates. The reinforcements likely carried a letter from R. M. Williamson with news that men were assembling in Gonzales and would join Fannin in coming to their rescue. At this point, Lindley calculated that the Alamo should have had approximately 164 effective men.

According to Lindley, up to 50 of Fannin's men, most of whom had been in Thomas H. Breece's company of New Orleans Greys, left Goliad to go to the rescue of their former mates. On March 3, these men joined the group waiting at Cibolo Creek for Fannin.

In 1876, Susannah Dickinson said that Travis sent three men out shortly after dark on March 3, probably in response to the arrival of the Mexican reinforcements. The three men, who Dickinson believed included Davy Crockett, were sent to find Fannin. Lindley stated that just before midnight, Crockett and one of the other men found the force of Texians waiting along Cibolo Creek, who had advanced to within 20 miles (32 km) of the Alamo. Just before daylight on March 4, part of the Texian force managed to break through the Mexican lines and enter the Alamo. A second group was driven across the prairie by Mexican soldiers. Almonte's journal reported that there was an engagement that night, but that the Mexican troops had repulsed the assault.

Assault preparations

Santa Anna called his senior officers together on the afternoon of March 4 and proposed an assault on the fort. Many of his officers recommend that the battle wait for the two 12-lb cannons, anticipated to arrive on March 7. A local woman, likely Juana Navarro Alsbury, approached Santa Anna that evening and likely attempted to negotiate a surrender for the Alamo defenders. According to many historians, this visit likely increased Santa Anna's impatience; as Todish noted, "there would have been little glory in a bloodless victory". The following morning, Santa Anna announced to his staff that the assault would take place early on March 6.

That evening, James Allen became the last courier to leave the Alamo, carrying personal messages from Travis and several of the other men.ref>Edmondson (2000), p. 360.</ref> Legend holds that at some point on March 5, Travis gathered his men and explained that an attack was likely imminent, and that the Mexican Army would likely prevail. He supposedly drew a line in the sand and asked those willing to die for the Texian cause to cross and stand alongside him. A bedridden Bowie requested that Crockett and several others carry his cot over the line, leaving only one man, Louis "Moses" Rose on the other side. Explaining that he was not yet ready to die, Rose escaped that evening. This episode was first mentioned in a newspaper article written thirty-five years after the Alamo fell by a reporter who said his parents heard the story directly from Rose. The reporter had admitted to embellishing pieces of the article, and as Rose had died by the time the story was published, so the story could not be authenticated. Years after the story was published, Alamo survivors Susannah Dickinson and Enrique Esparza mentioned the incident, but many details conflicted.

At 10 pm, the Mexican artillery ceased their bombardment. As Santa Anna had planned, the exhausted Texians soon fell into a deep sleep, the first uninterrupted sleep many had gotten since the siege began.

Final assault

Exterior fighting

Just after midnight on March 6 the Mexican army began preparing for the final assault. The men were divided into four columns. Cos commanded the first column of 350 men, which comprised 6 line infantry companies and 1 light infantry company from the Aldama Battalion, as well as 3 line infantry companies from the San Luis Battalion. These men were assigned 10 ladders, 2 crowbars, and 2 axes. The second column, consisting of 400 men under Colonel Francisco Duque, comprised 6 line infantry and 1 cazador company of the Toluca Battalion with the remaining 3 line infantry companies from the San Luis Battalion, who would have a combined 10 ladders. A third column, under Colonel Jose Marie Romero, contained 400 men from 12 line infantry companies, carrying 6 ladders. Colonel Juan Morales commanded the final column of 125 soldiers from light infantry and cazador companies, carrying 2 ladders. Four hundred reserves, including five grenadier companies, remained in camp under the authority of Santa Anna, while the Mexican cavalry were positioned around the Alamo to prevent escape of either Texians or Mexican soldiers. Each rifleman was assigned four rounds of ammunition and two flints, while grenadiers and scouts were given six rounds of ammunition each. Despite the bitter cold, the soldiers were ordered not to wear overcoats, which could impede their movements. Clouds concealed the moon, and thus the movements of the soldiers.

At 5:30 a.m. Santa Anna gave the order for the soldiers to begin the assault. They silently moved forward, with veterans positioned on the outside of the columns to better control the new recruits in the middle. Cos and his men approached the northwest corner of the Alamo, while Duque led his men from the northwest to the breach in the north wall of the Alamo. The column commanded by Romero marched towards the east wall, and Morales's column aimed for the low parapet by the chapel. In front of each column ranged several lines of light infantry, poised to "pick off any defenders who showed their heads". Although the Texians had posted three sentinels outside the walls, the men had fallen asleep and were killed before they could give an alert. Within the Alamo, only Captain John Baugh had remained awake.

When the Mexican soldiers noticed Santa Anna arriving at his position, they began shouting "Viva Santa Anna! Viva the Republic!". Jose Maria Gonzales, the bugler for the Zapadores Battalion, then sounded "Attention", then "Charge", then El Degüello, which signified that no quarter would be offered the defenders. The bugle anthems were soon repeated by bands from the other units. Baugh gave the alarm, and the Texians began rushing to their posts. Most of the noncombatants gathered in the church sacristy for safety; according to Susana Dickinson, before running to his post, Crockett stopped briefly in the chapel to pray. As Travis ran to his post, he shouted, "Come on boys, the Mexicans are upon us and we'll give them hell!" and, as he passed a group of Tejanos, "!No rendirse, muchachos!" ("No surrender, boys"). By this point, the Mexican army was already within musket range. Each Texian had four or five pre-loaded rifles with him, and began immediately firing into the oncoming Mexican army.

In the initial moments of the assault Mexican troops were at a disadvantage. In their column formation only the front rows of soldiers at a time could safely fire. Perhaps not realizing this the untrained recruits in the ranks "blindly fir their guns", and injured or killed the troops in front of them. The tight concentration of troops also offered an excellent target for the Texian artillery. Lacking canister shot, Texians filled their cannon with any metal they could find, including door hinges, nails, and chopped-up horseshoes, essentially turning the cannon into giant shotguns. According to the diary of José Enrique de la Peña, "a single cannon volley did away with half the company of chasseurs from Toluca". Mexican Colonel Duque fell from his horse after suffering a wound in his thigh and was almost trampled by his own men. General Manuel Castrillon quickly assumed command of Duque's column.

Although some in the front of the Mexican ranks wavered, soldiers in the rear pushed them on. Soldiers of the first two columns gathered against the west and north walls, protected from Texian artillery and rifle fire. Some Texians leaned over the walls to fire into the massed troops, which left them exposed to Mexican fire. Travis was one of the first defenders to die; struck in the head with a musket ball as he discharged both barrels of his shotgun into the soldiers below, Travis fell down the artillery ramp. Mexican Sergeant Becerra later reported that "Travis died like a brave man with his rifle in his hand at the back of a cannon." Most of the Mexican ladders did not make it to the walls, as their bearers either died or escaped; those that arrived were poorly made. The few soldiers who were able to climb the ladders were quickly killed or beaten back. As the Texians discharged their previously loaded rifles, they found it increasingly difficult to reload while attempting to keep the walls free of ladders.

At the north end of the Alamo, the Mexican columns withdrew. Morales's column at the south retreated into huts near the southwest corner of the mission. The Mexican army regrouped and attacked again and were again repulsed. Now fifteen minutes into the battle, they attacked a third time. During the third strike, Romero's third column, aiming for the east wall, were exposed to cannon fire and shifted to the north, mingling with the second column. Cos's column, under fire from Texians on the west wall, also veered north, intermingling the three columns. When Santa Anna saw that the bulk of his army was massed against the north wall, he thought the army was being routed; "panicked", he sent the reserves into the same area. The Mexican soldiers closest to the north wall realized that a ladder was not necessary, as the makeshift wall contained many gaps and toeholds. One of the first to scale the 12 feet (3.7 m) wall was General Juan Amador; at his challenge, his men began swarming up the wall. Amador located the postern in the north wall and opened it, allowing Mexican soldiers to pour into the complex. The west wall had few defenders, and men in Cos's column began climbing through gun ports or boosting each other over the 11 feet (3.4 m) walls. As the Texian defenders abandoned the north wall and the northern end of the west wall, Texian gunners at the south end of the mission turned their cannon toward the north and began firing into the incoming Mexican soldiers. This left the south end of the mission unprotected, and Morales's men left the huts where they had taken refuge and raced to the mission. Within minutes they had climbed the walls and killed the gunners, gaining control of the Alamo's 18-lb cannon. By this time Romero's men had taken the east wall of the compound and were pouring in through the cattle pen.

Interior fighting

As previously planned, most of the Texians fell back to the barracks and the chapel. During the siege, Texians had carved holes in many of the walls of these rooms so that they would be able to fire. In the chapel, artillery officer Almaron Dickinson briefly left his post at the cannon to run to the sacristy, where he yelled to his wife, "Great God, Sue, the Mexicans are inside our walls! If they spare you, save my child." After quickly kissing his wife goodbye, Dickinson returned to his post. The defenders in the cattle pen retreated into the horse corral. Those carrying weapons fired into Romero's column. The small band of Texians, including Alamo quartermaster Eliel Melton, then scrambled over the low wall, circled behind the church and raced on foot for the east prairie, where no Mexican soldiers could be seen. Sesma's cavalry was waiting, however, and attacked. Dickinson and his artillery crew turned a cannon around and fired into the cavalry, probably inflicting some casualties. Nevertheless, all but one of these Texians were thought to have been killed by lance; the last man was shot while hiding under a bush.

Unable to reach the barracks, another group of Texians, stationed along the west wall, charged west for the San Antonio River. When the cavalry charged, the Texians took cover and began firing from a ditch. Sesma was forced to send reinforcements, and the Texians were eventually killed. Sesma reported that this skirmish involved 50 Texians, but Edmondson believes that number was inflated.

Crockett and his men were also too far from the barracks to be able to take shelter,. and were the last remaining group within the mission to be in the open. The men defended the low wall in front of the church, using their rifles as clubs and relying on knives. After a volley of fire from Mexican soldiers and a wave of Mexican soldiers with bayonets, the few remaining Texians in this group fell back toward the church. The Mexican army now controlled all of the outer walls and the interior of the Alamo compound except for the church and rooms along the east and west walls.

Lieutenant Jose Maria Torres of the Zapadores Battalion spied a Texian flag waving from the roof of one building and joined Lieutenant Damasio Martinez in climbing the building to replace the flag. Three other Mexican soldiers had died trying to do the same thing, and Martinez was shot as he climbed. Torres managed to raise the flag of Mexico before being mortally wounded.

Although the initial battle had lasted just over 20 minutes, it took another hour for the Mexican army to have complete control over the Alamo. The remaining defenders were ensconced in the barracks rooms. Each room had only one door which led into the courtyard and which had been "buttressed by semicircular parapets of dirt secured with cowhides". Some of the rooms even had trenches dug into the floor to provide some cover for the defenders. In the confusion, the Texians had neglected to spike their cannons before retreating. Mexican soldiers turned the cannons around and began blasting in doors of the rooms. As each door was blown off, Mexican soldiers would fire a volley of muskets into the dark room, then charge into the room for hand-to-hand combat. De la Pena's diary remarked that some Texians hung white flags through the doorways of their barracks rooms, but that they had no intentions of surrendering; a Mexican soldier who entered the room without firing would find himself attacked. It is likely that the defenders in the most distant rooms could hear the fighting at the other end of the building but they were forced to wait for their turn to fight.

Bowie's family, Gertrudis Navarro, Juana Navarro Alsbury and her son, were hiding in one of the rooms along the west wall. Navarro opened the door to their room to signal that they meant no harm. When Mexican soldiers threatened them, a Texian defender charged into the room to defend them; he was quickly killed, as was a young Tejano who took refuge in the room. A Mexican officer soon arrived and led the women to a spot along one of the walls where they would be relatively safe.

Too sick to participate in the battle, Bowie remained in his sickbed in one of the rooms. Eyewitnesses to the battle gave conflicting accounts of Bowie's death. Some witnesses maintained that they saw several Mexican soldiers enter Bowie's room, bayonet him, and carry him, alive, from the room. Other witnesses claimed that Bowie shot himself or was killed by soldiers while too weak to lift his head. Alcade Francisco Ruiz said that Bowie was found "dead in his bed." According to historian Wallace Chariton, the "most popular, and probably the most accurate" version is that Bowie died on his cot, "back braced against the wall, and using his pistols and his famous knife."

The last of the Texians to die were the eleven men manning the two 12-lb cannon in the chapel. The entrance to the church had been barricaded with sandbags, which the Texians were able to fire over. A shot from the 18-lb cannon destroyed the barricades, and Mexican soldiers entered the building after firing an initial musket volley. Dickinson's crew fired their cannon from the apse into the Mexican soldiers at the door. With no time to reload, the Texians, including Dickinson, Gregorio Esparza, and Bonham, grabbed rifles and fired before being bayoneted to death. Texian Robert Evans was master of ordnance and had been tasked with keeping the gunpowder from falling into Mexican hands. Wounded, he crawled towards the powder magazine but was killed by a musket ball with his torch only inches from the powder. If he had succeeded, the blast would have destroyed the church, killing the women and children hiding in the sacristy as well.

As soldiers approached the sacristy, one of the sons of defender Anthony Wolf stood to pull a blanket over his shoulders. In the dark, Mexican soldiers mistook him for an adult and killed him before realizing that the room contained only women and children. According to Edmondson, Wolf then ran into the room, grabbed his remaining son, and leaped with the child from the cannon ramp at the rear of the church; both were killed by musket shots before hitting the ground. Possibly the last Texian to die in battle was Jacob Walker, who attempted to hide behind Susannah Dickinson and the other women; four Mexican soldiers killed him in front of them. Another Texian, Brigido Guerrero, also sought refuge in the sacristy. Guerrero, who had deserted from the Mexican Army in December 1835, was spared after convincing the soldiers he was a prisoner of the Texians.

By 6:30 a.m. the battle for the Alamo was over. Mexican soldiers inspected each corpse, bayoneting any body that moved. Even with all of the Texians dead, Mexican soldiers continued to shoot, some killing each other in the confusion. Mexican generals were unable to stop the bloodlust and appealed to Santa Anna for help. Although he showed himself, the violence continued, and the buglers were finally ordered to sound a retreat. For 15 minutes after that, soldiers continued to fire into dead bodies.

Aftermath

When the firing ended Santa Anna joined his men inside the Alamo. According to many accounts of the battle, between five and seven Texians surrendered during the battle, possibly to General Castrillon. Edmondson speculates that these men might have been sick or wounded and were therefore unable to fight. Incensed that his orders had been ignored, Santa Anna demanded the immediate execution of the survivors. Although Castrillon and several other officers refused to do so, staff officers who had not participated in the fighting drew their swords and killed the unarmed Texians. Weeks after the battle, stories began to circulate that Crockett was among those who surrendered and were executed. However, Ben, a former American slave who acted as cook for one of Santa Anna's officers, maintained that Crockett's body was found surrounded by "no less than sixteen Mexican corpses", with Crockett's knife buried in one of them. Historians disagree on which story is accurate. According to Petite, "every account of the Crockett surrender-execution story comes from an avowed antagonist (either on political or military grounds) of Santa Anna's. It is believed that many stories, such as the surrender and execution of Crockett, were created and spread in order to discredit Santa Anna and add to his role as villain."

After the scene inside the Alamo had calmed, Santa Anna ordered that the face of every corpse be wiped clean so that they could positively identify which soldiers were Mexican and which were Texian. According to Francisco Ruiz, possibly the alcade of Bexar, he was ordered by Santa Anna to identify the bodies of Travis, Bowie, and Crockett. Lindley believes that Ruiz was not in Bexar at the time. Joe was also asked to point out Travis's body. With the identifications complete, Santa Anna ordered that the Texian bodies be stacked and burned. Crematng bodies was anathema at the time, as most people believed that a body could not be resurrected unless it where whole. The only exception was the body of Gregorio Esparza, whose brother, Francisco Esparza, served in Santa Anna's army and received permission to give Gregorio a proper burial. In his initial report Santa Anna claimed that 600 Texians had been killed, with only 70 Mexican soldiers killed and 300 wounded. His secretary, Ramon Martinez Caro, later remarked that he had not wished to make a false report but had done so under Santa Anna's orders. Other eyewitnesses claimed that between 182–257 Texians were killed. Francisco Ruiz counted 182 Texian bodies burned on the funeral pyre. A number of bodies were found in the fields north of the Alamo, likely those of men who had tried to escape but were killed by the cavalry. Some historians believe that at least one Texian, Henry Warnell, successfully escaped from the battle. Warnell died several months later of wounds incurred either during the final battle or during his escape as a courier.

The ashes were left where they fell until February 1837, when Juan Seguin and many members of his cavalry returned to Bexar to examine the remains. At Seguin's behest, the bells at the San Fernando Cathedral pealed all day. A local carpenter created a simple coffin, and ashes from the two smaller funeral pyres were placed inside. The names Travis, Crockett, and Bowie were inscribed on the lid. Seguin brought the coffin to the remaining funeral pyre; he buried both the coffin and the ashes from the largest funeral pyre on this location. The burial location was thought to be under a peach tree grove, but the spot was not marked and cannot now be identified. This event, and the vague burial location, was mentioned in a March 28, 1837 article in the Telegraph and Texas Register. However, in 1899 Seguin claimed that he had placed the coffin in front of the altar at the San Fernando Cathedral. A coffin was discovered buried before the altar in July 1936, but according to historian Wallace Chariton it is unlikely to actually contain the remains of the Alamo defenders. Fragments of uniforms were found in the coffin, and it is known that the Alamo defenders did not wear uniforms.

Estimates of the number of Mexican soldiers who died ranged from 60–2000, with an additional 250–300 wounded. Most Alamo historians agree that 400–600 Mexicans were killed or wounded. This would represent about one-third of the Mexican soldiers involved in the final assault, which Todish remarks is "a tremendous casualty rate by any standards".

Santa Anna reportedly told Captain Fernando Urizza that the battle "was but a small affair". Lieutenant Colonel José Juan Sanchez Navarro, however, realized the outcome was a Pyrrhic victory and remarked that "with another such victory as this, we'll go to the devil". Santa Anna ordered Ruiz to supervise the burial of the Mexican soldiers in the local cemetery, Campo Santo. Ruiz claimed that the graveyard was near full and that he instead threw some of the corpses in the river. However, in a report that Sam Houston filed on March 13, he said that all Mexicans were buried.

Santa Anna spared several others. Travis's slave, Joe and Sam, Bowie's freedman, were both spared because they were or had been slaves. Santa Anna hoped that by freeing these men, other slaves in Texas would support the Mexican government over the Texian rebellion. The surviving noncombatants were interviewed individually by Santa Anna on March 7. Impressed with Susanna Dickinson, Santa Anna offered to adopt her infant daughter Angelina and have the child educated in Mexico City. Susanna Dickinson refused the offer, which was not extended to Juana Navarro Alsbury for her son who was of similar age. Each woman was given a blanket and two silver pesos. The Tejano women were allowed to return to their homes in Bexar; Dickinson, her daughter, and Joe were sent to Gonzales, escorted by Ben. Before they were allowed to leave, Santa Anna ordered that the surviving members of the Mexican army parade in a grand review, in the hopes that Joe and Dickinson would deliver a warning to the remainder of the Texian forces that his army was unbeatable.

Travis's March 3 dispatch to the Texas provisional government on the morning of March 6. Unaware that the fort had fallen, delegate Robert Potter called for the convention to adjourn and march immediately to relieve the Alamo. Sam Houston convinced the delegates to remain in Washington-on-the-Brazos to develop a constitution and then left to take command of the volunteers that Colonel James C. Neill and Major R.M. "Three-Legged Willie" Williamson had been gathering in Gonzales. Houston arrived in Gonalez on March 11 to find 400 Texian volunteers waiting. Later that day Andres Barcenas and Anselmo Bergaras arrived in Gonzales from Bexar to report that the Alamo had fallen with all men slain. Houston arrested the men as enemy spies in the hopes of halting a panic, and then sent scouts Deaf Smith and Henry Karnes to find out the truth. They travelled fewer than 20 miles (32 km) west before finding Susannah Dickinson and Joe. On hearing their news, Houston advised all civilians in the area to evacuate and ordered the army to retreat. This sparked a mass exodus of Texians from the Anglo settlements, including the government, which also fled east.

Despite their losses at the Alamo the Mexican army in Texas outnumbered the Texian army by almost 6 to 1. Santa Anna assumed that all Texian resistance would crumble, and that Texian soldiers would quickly leave the province. He was, therefore, in no hurry to leave Bexar. However, the news of the Alamo's fall had the opposite affect, and men flocked to Houston's army. The New York Post editorialized that "had treated the vanquished with moderation and generosity, it would have been difficult if not impossible to awaken that general sympathy for the people of Texas which now impels so many adventurous and ardent spirits to throng to the aid of their brethern". Despite a strong wish among the Texian army to avenge their loss at the Alamo, for several weeks Houston led his army on a retreat into East Texas. On the afternoon of April 21 the Texian army attacked Santa Anna's camp near Lynchburg Ferry. The Mexican army was taken by surprise, and the Battle of San Jacinto was essentially over after 18 minutes. During the fighting, many of the Texian soldiers repeatedy cried "Remember the Alamo!" Santa Anna was captured the following day, and reportedly told Houston "That man may consider himself born to no common destiny who has conquered the Napoleon of the West. And now it remains for him to be generous to the vanquished." Houston replied, "You should have remembered that at the Alamo". Santa Anna was forced to order his troops out of Texas, ending Mexican control of the province, now known as the Republic of Texas.

Legacy

As the Mexican army retreated from Texas following the Battle of San Jacinto, they tore down many of the walls and burned the palisade which Crockett had defended. Within the next several decades, various buildings in the complex were torn down, and in 1849 a gable was added to the top of the chapel. Today, the remnants of the Alamo are near the San Antonio town center. The church building remains standing and serves as an official state shrine to the Texian defenders. As the 20th century began many Texans advocated razing the remaining building. A wealthy rancher's daughter, Clara Driscoll, purchased the building to serve as a museum. The Texas Legislature later bought the property and appointed the Daughters of the Republic of Texas as permanent caretakers. In front of the church, in the center of Alamo Plaza, stands a cenotaph, designed by Pompeo Coppini and erected in 1939, which commemorates the Texians who died during the battle. According to Bill Groneman's Battlefields of Texas, the Alamo has become "the most popular tourist site in Texas".

Popular culture

Many of the Mexican officers who participated in the battle left memoirs, although some were not written until decades after the battle. Among those who provided written accounts of the battle were Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, Vicente Filisola, José Enrique de la Peña, Jose Juan Sanchez Navarro, Juan N. Almonte, and Francisco Becerra. Texians Juan Seguin and John Sutherland also left memoirs, although some historians believe Sutherland was not at the Alamo and wrote his memoirs from heresay. The first report of the names of the Texian victims of the battle came in the March 24, 1836 issue of the Telegraph and Texas Register. The 115 names on the list came from John Smith and Gerald Navan, who had left as couriers. In 1843 former Texas Ranger and amateur historian John Henry Brown wrote and published the first history of the battle, a pamphlet called The Fall of the Alamo. He followed this in 1853 with a second pamphlet called Facts of the Alamo, Last Days of Crockett and Other Sketches of Texas. No copies of the pamphlets have survived. The next major treatment of the battle was Reuben Potter's The Fall of the Alamo, published in The Magazine of American History in 1878. Potter based his work on interviews with many of the survivors of the Battle of the Alamo. One of the most used secondary sources about the Alamo is Amelia W. Williams's doctoral dissertation, "Critical Study of the Siege of the Alamo and of the Personnel of Its Defenders". Completed in 1931, it attempted to positively identify all of the Texians who died during the battle. Her list was used to choose the names carved into the cenotaph memorial in 1936. Several historians, including Thomas Ricks Lindley, Thomas Lloyd Miller, and Richard G. Santos, believe her list included men who had not died at the Alamo. Despite the errors in some of her work, Williams collect a large amount of information and her work serves as a starting point for many historians. The first full-length, non-fiction book covering the battle was not published until 1948, when John Myers Myers's The Alamo was released.

According to Todish et al, "there can be little doubt that most Americans have probably formed many of their opinions on what occurred at the Alamo not from books, but from the various movies made about the battle." The first film version of the battle appeared in 1911, when Gaston Melies directed The Immortal Alamo, which has since been lost. Through the next four decades several other movies were released, variously focusing on Davy Crocket, Almeron Dickinson, and Louis Rose. The Alamo achieved prominence on television in 1955 with Walt Disney's Davy Crockett: King of the Wild Frontier, which was largely based on myth. In the early 1950s John Wayne began developing a film based on the Battle of the Alamo. When he left his contract with Republic Pictures he was forced to leave behind a partial script. Republic Pictures had the script finished and developed into the 1955 movie The Last Command. Although the film had its historical inaccuracies, it was the most detailed of the films on the Texas Revolution. Wayne continued to develop an Alamo movie, resulting in the 1960 film The Alamo, starring Wayne as Davy Crockett. Although screenwriter James Edward Grant claimed to have done extensive historical research, according to Todish "there is not a single scene in The Alamo which corresponds to an historically verifiable incident", and historians J. Frank Dobie and Lon Tinkle demanded that their names be removed from the credits as historical advisors. The set built for the movie, Alamo Village, includes a replica of the Alamo Mission and the city of San Antonio and is still used as an active movie set.

As the 150th anniversary of the battle approached in the 1980s, several additional movies were made about the Alamo, including the made-for-television movie The Alamo: Thirteen Days to Glory, which Nofi regards as the most historically accurate of all Alamo films. The movie Todish calls "the best theatrical film ever made about the Alamo" was also filmed in the 1980s. Filmed in IMAX format using historical reenactors instead of professional actors, Alamo ... The Price of Freedom is shown only in San Antonio, with several views per day at a theater near the Alamo. It runs only 45 minutes but has "an attention to detail and intensity that are remarkable". In 2004 another film, also called The Alamo, was released. Described by CNN as possibly "the most character-driven of all the movies made on the subject", the movie starred Billy Bob Thornton as Crockett, Dennis Quaid as Sam Houston, and Jason Patric as Bowie.

A number of songwriters have also been inspired by the Battle of the Alamo. Tennessee Ernie Ford's "The Ballad of Davy Crockett" spent 16 weeks on the country music charts, peaking at number 4 in 1955. Marty Robbins recorded a version of the song "The Ballad of the Alamo" in 1960 which spent 13 weeks on the pop charts, peaking at number 34.

See also

- List of Alamo defenders

- List of Texan survivors of the Battle of the Alamo

- List of Texas Revolution battles

- Famous Last stands

Notes

- According to Todish et al (1998), p. 54, the Texian defender was either Edwin Mitchell or Napolean Mitchell; Alsbury knew only his last name.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 374 claims that this remark was made by Colonel Juan Almonte, and overheard by Almonte's cook, Ben.

References

- Todish et al (1998), p. 6.

- ^ Barr (1990), p. 56.

- Barr (1990), p. 63.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 29.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 30.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 31.

- Todish et al (1998), p. 10.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 111.

- Lord (1961), p. 59.

- Hardin (1994), p. 98.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 99.

- Todish et al (1998), p. 20.

- Scott (2000), p. 73.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 102.

- ^ Scott (2000), p. 71.

- Scott (2000), p. 74.

- Scott (2000), p. 75.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 103.

- Hardin (1994), p. 105.

- Lord (1961), p. 67.

- Lord (1961), p. 68.

- Lord (1961), p. 73.

- Scott (2000), p. 77.

- Hopewell (1994), p. 112.

- Hopewell (1994), p. 113.

- Hopewell (1994), p. 114.

- ^ Hopewell (1994), p. 115.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 117.

- Lord (1961), p. 81.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 32.

- ^ Hopewell (1994), p. 116.

- Hardin (1994), p. 120.

- Lord (1961), p. 86.

- ^ Lord (1961), p. 87.

- Meyers (1948), p. 131.

- Hardin (1994), p. 121.

- Petite (1999), p. 26.

- Lord (1961), p. 89.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 36.

- ^ Nofi (1992), p. 76.

- Lindley (2003), p. 87.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 299.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 301.

- Lord (1961), p. 95.

- ^ Nofi (1992), p. 78.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 40.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), pp. 40–41.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 308.

- Todish et al (1998), p. 41.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 310.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 42.

- Nofi (1992), p. 81.

- Lord (1961), p. 107.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 43.

- Tinkle (1985), p. 121.

- Scott (2000), p. 102.

- ^ Lindley (2003), p. 139.

- Todish et al (1998), p. 47.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 349.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 304.

- ^ Tinkle (1985), p. 118.

- Lord (1961), p. 109.

- ^ Tinkle (1985), p. 119.

- Tinkle (1985), p. 120.

- Tinkle (1985), p. 122.

- Petite (1999), p. 34.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 132.

- Nofi (1992), p. 83.

- Todish et al (1998), p. 44.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 325.

- Lindley (2003), p. 89.

- Lord (1961), p. 105.

- ^ Nofi (1992), p. 80.

- Petite (1998), p. 88.

- Petite (1998), p. 90.

- Lord (1961), p. 111.

- Myers (1948), p. 200.

- Tinkle (1985), p. 149.

- Tinkle (1985), p. 162.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 324.

- Nofi (1992), p. 95.

- Scott (2000), p. 100.

- Scott (2000), p. 101.

- Lindley (2003), pp. 123–4, 127–8.

- ^ Lindley (2003), p. 130.

- Tinkle (1985), p. 163.

- Lindley (2003), p. 131.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 340.

- Lindley (2003), p. 133.

- Lindley (2003), p. 137.

- Lindley (2003), p. 138.

- Lindley (2003), p. 140.

- Lindley (2003), p. 142.

- Lindley (2003), p. 143.

- Todish et al (1998), p. 48.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 355.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 49.

- Hopewell (1994), p. 126.

- Chariton (1992), p. 195.

- Groneman (1996), pp. 122, 150, 184.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 51.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 362.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 356.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 357.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 50.

- ^ Lord (1961), p. 160.

- Hardin (1994), p. 138.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 139.

- ^ Tinkle (1985), p. 196.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 363.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 52.

- Petite (1998), p. 113.

- Hardin (1994), p. 146.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 364.

- Tinkle (1985), p. 212.

- ^ Hardin (1994), p. 147.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 53.

- Petite (1998), p. 112.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 366.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 367.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 368.

- Lord (1961), p. 162.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 369.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 54.

- ^ Petite (1998), p. 114.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 370.

- Lord (1961), p. 165.

- Groneman (1996), p. 214.

- ^ Hopewell (1994), p. 127.

- Chariton (1992), p. 74.

- Petite (1998), p. 115.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 371.

- Tinkle (1985), p. 216.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 372.

- Tinkle (1985), p. 218.

- ^ Lord (1961), p. 166.

- Groneman (1990), p. 55–56.

- ^ Tinkle (1985), p. 220.

- Nofi (1992), p. 123.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 373.

- ^ Petite (1998), p. 123.

- Hardin (1994), p. 148.

- Tikle (1985), p. 214.

- Petite (1998), p. 124.

- Lindley (2003), p. 278.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 374.

- Petite (1998), p. 139.

- Hardin (1994), p. 156.

- Nofi (1992), p. 133.

- ^ Nofi (1992), p. 126.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 407.

- Groneman (1990), p. 119.

- Petite (1998), p. 131.

- Petite (1998), p. 132.

- Chariton (1990), p. 78.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 55.

- Hardin (1961), p. 155.

- Nofi (1992), p. 136.

- Lord (1961), p. 167.

- Lindley (2003), p. 277.

- Petite (1998), p. 128.

- Petite (1998), p. 127.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 377.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 375.

- Nofi (1992), p. 138.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 376.

- Todish et al (1998), p. 67.

- Todish et al (1998), p. 68.

- Lord (1961), p. 190.

- ^ Edmondson (2000), p. 378.

- Hardin (1994), p. 158.

- Lord (1961), p. 169.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 69.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 70.

- Todish et al (1998), p. 198.

- ^ Groneman (1998), p. 52.

- Todish et al (1998), p. 199.

- Groneman (1998), p. 56.

- ^ Nofi (1992), p. 211.

- Nofi (1992), p. 212.

- Lindley (2003), p. 115.

- Chariton (1990), p. 180.

- ^ Lindley (2003), p. 106.

- Lindley (2003), p. 37.

- Lindley (2003), p. 41.

- Lindley (2008), p. 68.

- Cox, Mike (March 6, 1998), "Last of the Alamo big books rests with 'A Time to Stand'", The Austin-American Statesman

- Todish et al (1998), p. 187.

- ^ Nofi (1992), p. 213.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 188.

- ^ Todish et al (1998), p. 190.

- Todish et al (1998), p. 191.

- Culpepper, Andy (April 8, 2004), A different take on 'The Alamo', CNN, retrieved 2008-05-22

- Todish et al (1998), p. 194.

- Todish et al (1998), p. 196.

References

- Barr, Alwyn (1996), Black Texans: A history of African Americans in Texas, 1528–1995 (2nd ed.), Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 080612878X

- Chariton, Wallace O. (1990), Exploring the Alamo Legends, Dallas, TX: Republic of Texas Press, ISBN 9781556222559

- Edmondson, J.R. (2000), The Alamo Story-From History to Current Conflicts, Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press, ISBN 1-55622-678-0

- Groneman, Bill (1990), Alamo Defenders, A Genealogy: The People and Their Words, Austin, TX: Eakin Press, ISBN 089015757X

- Groneman, Bill (1996), Eyewitness to the Alamo, Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press, ISBN 1556225024

- Groneman, Bill (1998), Battlefields of Texas, Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press, ISBN 9781556225710

- Hardin, Stephen L. (1994), Texian Iliad, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-73086-1

- Hopewell, Clifford (1994), James Bowie Texas Fighting Man: A Biography, Austin, TX: Eakin Press, ISBN 0890158819

- Lindley, Thomas Ricks (2003), Alamo Traces: New Evidence and New Conclusions, Lanham, MD: Republic of Texas Press, ISBN 1556229836

- Lord, Walter (1961), A Time to Stand, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0803279027

- Manchaca, Martha (2001), Recovering History, Constructing Race: The Indian, Black, and White Roots of Mexican Americans, The Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long Series in Latin American and Latino Art and Culture, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0292752539

- Myers, John Myers (1948), The Alamo, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0803257791

- Nofi, Albert A. (1992), The Alamo and the Texas War of Independence, September 30, 1835 to April 21, 1836: Heroes, Myths, and History, Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, Inc., ISBN 0938289101

- Petite, Mary Deborah (1999), 1836 Facts about the Alamo and the Texas War for Independence, Mason City, IA: Savas Publishing Company, ISBN 188281035X

- Scott, Robert (2000), After the Alamo, Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press, ISBN 9781556226915

- Shackford, James Atkins (1994), David Crockett: The Man and the Legend, Bison Books, ISBN 978-0803292307

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Tinkle, Lon (1985), 13 Days to Glory: The Siege of the Alamo, College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 0890962383. Reprint. Originally published: New York: McGraw-Hill, 1958

- Todish, Timothy J.; Todish, Terry; Spring, Ted (1998), Alamo Sourcebook, 1836: A Comprehensive Guide to the Battle of the Alamo and the Texas Revolution, Austin, TX: Eakin Press, ISBN 9781571681522

Further reading

- Borroel,Roger, "THE TEXAN REVOLUTION OF 1836", La Villita Pbns., ISBN 1-928792-09-X.

- Crisp, James E., Sleuthing the Alamo, Oxford University Press (2005) ISBN 0-19-516349-4

- Davis, William C., Lone Star Rising: The Revolutionary Birth of the Texas Republic, Free Press (2004) ISBN 0-684-86510-6

- Hardin, Stephen L., The Alamo 1836, Santa Anna's Texas Campaign, Osprey Campaign Series #89, Osprey Publishing (2001).

External links

| Battle of the Alamo | |

|---|---|

| Siege | |

| Defenders | |

| Mexican commanders | |

| Texian survivors | |

| Legacy |

|

| See also | |

29°25′32″N 98°29′10″W / 29.42556°N 98.48611°W / 29.42556; -98.48611

Categories: