This is an old revision of this page, as edited by ARYAN818 (talk | contribs) at 19:41, 26 September 2008. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:41, 26 September 2008 by ARYAN818 (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Chess (disambiguation). From left to right, a white king, a black rook, a black queen, a white pawn, a black knight, and a white bishop From left to right, a white king, a black rook, a black queen, a white pawn, a black knight, and a white bishop | |

| Players | 2 |

|---|---|

| Setup time | Under one minute |

| Playing time | Casual games without time control last usually 10–60 minutes |

| Skills | Tactics, Strategy |

Chess is a recreational and competitive game, originating in India,. It is played between two players. Sometimes called Western chess or international chess to distinguish it from its predecessors and other chess variants, the current form of the game emerged in Southern Europe during the second half of the 15th century after evolving from similar, much older games of Indian and Persian origin. Today, chess is one of the world's most popular games, played by millions of people worldwide in clubs, online, by correspondence, in tournaments and informally.

The game is played on a square chequered chessboard with 64 squares arranged in an eight-by-eight square. At the start, each player (one controlling the white pieces, the other controlling the black pieces) controls sixteen pieces: one king, one queen, two rooks, two knights, two bishops, and eight pawns. The object of the game is to checkmate the opponent's king, whereby the king is under immediate attack (in "check") and there is no way to remove it from attack on the next move.

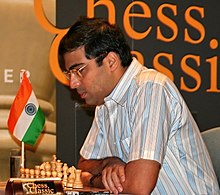

The tradition of organized competitive chess started in the sixteenth century and has developed extensively. Chess today is a recognized sport of the International Olympic Committee. The first official World Chess Champion, Wilhelm Steinitz, claimed his title in 1886; Viswanathan Anand is the current World Champion. Theoreticians have developed extensive chess strategies and tactics since the game's inception. Aspects of art are found in chess composition.

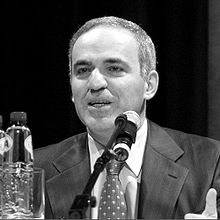

One of the goals of early computer scientists was to create a chess-playing machine, and today's chess is deeply influenced by the abilities of current chess programs and the ability to play other players online. In 1997, Deep Blue became the first computer to beat the reigning World Champion in a match when it defeated Garry Kasparov by a score of 3.5-2.5.

Rules

Main article: Rules of chessFor a simple demonstration of the gameplay, see sample chess game.

Setup

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Chess is played on a square board of eight rows (called ranks and denoted with numbers 1 to 8) and eight columns (called files and denoted with letters a to h) of squares. The colors of the sixty-four squares alternate and are referred to as "light squares" and "dark squares". The chessboard is placed with a light square at the right hand end of the rank nearest to each player, and the pieces are set out as shown in the diagram, with each queen on its own color.

The pieces are divided, by convention, into white and black sets. The players are referred to as "White" and "Black", and each begins the game with sixteen pieces of the specified color. These consist of one king, one queen, two rooks, two bishops, two knights and eight pawns. White moves first. The players alternate moving one piece at a time (with the exception of castling, when two pieces are moved simultaneously). Pieces are moved to either an unoccupied square, or one occupied by an opponent's piece, capturing it and removing it from play. With one exception (en passant), all pieces capture opponent's pieces by moving to the square that the opponent's piece occupies.

When a king is under immediate attack by one or two of the opponent's pieces, it is said to be in check. The only permissible responses to a check are to capture the checking piece, interpose a piece between the checking piece and the king, or move the king to a square where it is not under attack. Castling is not a permissible response to a check. A move that would place the moving player's king in check is illegal. The object of the game is to checkmate the opponent; this occurs when the opponent's king is in check, and there is no way to remove it from attack.

Moves

Each chess piece has its own style of moving. The X's mark the squares where the piece can move if no other pieces are on the X's between the piece's initial position and destination. If there is an opponent's piece at the destination square, then moving piece can capture the opponent's piece. The only exception is the pawn which can only capture the white circles.

Moves of a king| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Special moves

Castling

Main article: Castling

Once in every game, each king is allowed to make a special move, known as castling. Castling consists of moving the king two squares towards a rook, then placing the rook immediately on the far side of the king. Castling is only permissible if all of the following conditions hold:

- Neither of the pieces involved in the castling may have been previously moved during the game;

- There must be no pieces between the king and the rook;

- The king may not currently be in check, nor may the king pass through squares that are under attack by enemy pieces. As with any move, castling is illegal if it would place the king in check.

- The king and the rook must be on the same rank (to exclude castling with a promoted pawn, described later).

En passant

Main article: En passant Special pawn moves| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

When a pawn advances two squares, if there is an opponent's pawn on an adjacent file next to its destination square, then the opponent's pawn can capture it and move to the square the pawn passed over, but only on the next move. For example, if the black pawn has just advanced two squares from f7 to f5, then either of the white pawns on e5 and g5 can take it via en passant on f6.

Promotion

Main article: Promotion (chess)When a pawn advances to its eighth rank, it is exchanged for the player's choice of a queen, rook, bishop, or knight of the same color. Usually, the pawn is chosen to be promoted to a queen, but in some cases another piece is chosen, called underpromotion. In the diagram on the right, the pawn on c7 can choose to advance to the eighth rank to promote to a better piece.

End of the game

Chess games do not have to end in checkmate — either player may resign if the situation looks hopeless. Games also may end in a draw (tie). A draw can occur in several situations, including draw by agreement, stalemate, threefold repetition of a position, the fifty move rule, or a draw by impossibility of checkmate (usually because of insufficient material to checkmate).

Time control

Besides casual games without exact timing, chess is also played with a time control, mostly by club and professional players. If a player's time runs out before the game is completed, the game is automatically lost (provided his opponent has enough pieces left to deliver checkmate). The timing ranges from long games played up to seven hours to shorter rapid chess games lasting usually 30 minutes or one hour per game. Even shorter is blitz chess with a time control of three to fifteen minutes for each player and bullet chess (under three minutes).

The international rules of chess are described in more detail in the FIDE Handbook, section Laws of Chess.

Strategy and tactics

Chess strategy consists of setting and achieving long-term goals during the game — for example, where to place different pieces — while tactics concentrate on immediate maneuver. These two parts of chess thinking cannot be completely separated, because strategic goals are mostly achieved by the means of tactics, while the tactical opportunities are based on the previous strategy of play.

Because of different strategic and tactical patterns, a game of chess is usually divided into three distinct phases: opening, usually the first 10 to 25 moves, when players develop their armies and set up the stage for the coming battle; middlegame, the developed phase of the game; and endgame, when most of the pieces are gone and kings start to take an active part in the struggle.

Fundamentals of strategy

Main article: Chess strategyChess strategy is concerned with evaluation of chess positions and with setting up goals and long-term plans for the future play. During the evaluation, players must take into account the value of pieces on board, pawn structure, king safety, space, and control of key squares and groups of squares (for example, diagonals, open-files, and dark or light squares).

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The most basic step in evaluating a position is to count the total value of pieces of both sides. The point values used for this purpose are based on experience; usually pawns are considered worth one point, knights and bishops about three points each, rooks about five points (the value difference between a rook and a bishop being known as the exchange), and queens about nine points. In the endgame, the king is generally more powerful than a minor piece but less powerful than a rook, thus it is sometimes assigned a fighting value of four points. These basic values are then modified by other factors like position of the piece (for example, advanced pawns are usually more valuable than those on initial positions), coordination between pieces (for example, a pair of bishops usually coordinates better than the pair of a bishop and knight), or type of position (knights are generally better in closed positions with many pawns while bishops are more powerful in open positions).

Another important factor in the evaluation of chess positions is the pawn structure (sometimes known as the pawn skeleton), or the configuration of pawns on the chessboard. Pawns being the least mobile of the chess pieces, the pawn structure is relatively static and largely determines the strategic nature of the position. Weaknesses in the pawn structure, such as isolated, doubled or backward pawns and holes, once created, are usually permanent. Care must therefore be taken to avoid them unless they are compensated by another valuable asset (for example, by the possibility to develop an attack).

Fundamentals of tactics

Main article: Chess tactics

In chess, tactics in general concentrate on short-term actions — so short-term that they can be calculated in advance by a human player or by a computer. The possible depth of calculation depends on the player's ability or speed of the processor. In quiet positions with many possibilities on both sides, a deep calculation is not possible, while in "tactical" positions with a limited number of forced variants, it is possible to calculate very long sequences of moves.

Simple one-move or two-move tactical actions — threats, exchanges of material, double attacks etc. — can be combined into more complicated variants, tactical maneuvers, often forced from one side or from both. Theoreticians described many elementary tactical methods and typical maneuvers, for example pins, forks, skewers, discovered attacks (especially discovered checks), zwischenzugs, deflections, decoys, sacrifices, underminings, overloadings, and interferences.

A forced variant which is connected with a sacrifice and usually results in a tangible gain is named a combination. Brilliant combinations — such as those in the Immortal game — are described as beautiful and are admired by chess lovers. Finding a combination is also a common type of chess puzzle aimed at development of players' skills.

Opening

Main article: Chess openingA chess opening is the group of initial moves of a game (the "opening moves"). Recognized sequences of opening moves are referred to as openings and have been given names such as the Ruy Lopez or Sicilian Defence. They are catalogued in reference works such as the Encyclopaedia of Chess Openings.

There are dozens of different openings, varying widely in character from quiet positional play (e.g. the Réti Opening) to very aggressive (e.g. the Latvian Gambit). In some opening lines, the exact sequence considered best for both sides has been worked out to 30–35 moves or more. Professional players spend years studying openings, and continue doing so throughout their careers, as opening theory continues to evolve.

The fundamental strategic aims of most openings are similar:

- Development: To place (develop) the pieces (particularly bishops and knights) on useful squares where they will have an impact on the game.

- Control of the center: Control of the central squares allows pieces to be moved to any part of the board relatively easily, and can also have a cramping effect on the opponent.

- King safety: Correct timing of castling can enhance this.

- Pawn structure: Players strive to avoid the creation of pawn weaknesses such as isolated, doubled or backward pawns, and pawn islands.

Apart from these fundamentals, other strategic plans or tactical sequences may be employed in the opening.

Most players and theoreticians consider that White, by virtue of the first move, begins the game with a small advantage. Black usually strives to neutralize White's advantage and achieve equality, or to develop dynamic counterplay in an unbalanced position.

Middlegame

Main article: Chess middlegameThe middlegame is the part of the game when most pieces have been developed. Because the opening theory has ended, players have to assess the position, to form plans based on the features of the positions, and at the same time to take into account the tactical possibilities in the position.

Typical plans or strategical themes — for example the minority attack, that is the attack of queenside pawns against an opponent who has more pawns on the queenside — are often appropriate just for some pawn structures, resulting from a specific group of openings. The study of openings should therefore be connected with the preparation of plans typical for resulting middlegames.

Middlegame is also the phase in which most combinations occur. Middlegame combinations are often connected with the attack against the opponent's king; some typical patterns have their own names, for example the Boden's Mate or the Lasker—Bauer combination.

Another important strategical question in the middlegame is whether and how to reduce material and transform into an endgame (i.e. simplify). For example, minor material advantages can generally be transformed into victory only in an endgame, and therefore the stronger side must choose an appropriate way to achieve an ending. Not every reduction of material is good for this purpose; for example, if one side keeps a light-squared bishop and the opponent has a dark-squared one, the transformation into a bishops and pawns ending is usually advantageous for the weaker side only, because an endgame with bishops on opposite colors is likely to be a draw, even with an advantage of one or two pawns.

Endgame

Main article: Chess endgame| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

The endgame (or end game or ending) is the stage of the game when there are few pieces left on the board. There are three main strategic differences between earlier stages of the game and endgame:

- During the endgame, pawns become more important; endgames often revolve around attempting to promote a pawn by advancing it to the eighth rank.

- The king, which has to be protected in the middlegame owing to the threat of checkmate, becomes a strong piece in the endgame. It is often brought to the center of the board where it can protect its own pawns, attack the pawns of opposite color, and hinder movement of the opponent's king.

- Zugzwang, a disadvantage because the player has to make a move, is often a factor in endgames but rarely in other stages of the game. For example, in the diagram on the right, Black on move must play 1...Kb7 and allow white to queen after 2.Kd7, while White on move must allow a draw either after 1.Kc6 stalemate or lose the last pawn by going anywhere else.

Endgames can be classified according to the type of pieces that remain on board. Basic checkmates are positions in which one side has only a king and the other side has one or two pieces and can checkmate the opposing king, with the pieces working together with their king. For example, king and pawn endgames involve only kings and pawns on one or both sides and the task of the stronger side is to promote one of the pawns. Other more complicated endings are classified according to the pieces on board other than kings, e.g. "rook and pawn versus rook endgame".

History

Predecessors

Main article: Origins of chess

Chess originated in India, where its early form in the 6th century was chaturanga, which translates as "four divisions of the military" – infantry, cavalry, elephants, and chariots, represented respectively by pawn, knight, bishop, and rook. In Persia around 600 the name became shatranj and the rules were developed further. Shatranj was taken up by the Muslim world after the Islamic conquest of Persia, with the pieces largely retaining their Persian names. In Spanish "shatranj" was rendered as ajedrez, in Portuguese as xadrez, and in Greek as zatrikion, but in the rest of Europe it was replaced by versions of the Persian shāh ("king").

The game reached Western Europe and Russia by at least three routes, the earliest being in the 9th century. By the year 1000 it had spread throughout Europe. Introduced into the Iberian Peninsula by the Moors in the 10th century, it was described in a famous 13th century manuscript covering shatranj, backgammon, and dice named the Libro de los juegos.

Another theory, championed by David H. Li, contends that chess arose from the game xiangqi, or at least a predecessor thereof, existing in China since the 2nd century BC.

Origins of the modern game (1450–1850)

Around 1200, rules of shatranj started to be modified in southern Europe, and around 1475, several major changes rendered the game essentially as it is known today. These modern rules for the basic moves had been adopted in Italy and in Spain. Pawns gained the option of advancing two squares on their first move, while bishops and queens acquired their modern abilities. This made the queen the most powerful piece; consequently modern chess was referred to as "Queen's Chess" or "Mad Queen Chess". These new rules quickly spread throughout western Europe, with the exception of the rules about stalemate, which were finalized in the early nineteenth century.

This was also the time when chess started to develop a corpus of theory. The oldest preserved printed chess book, Repetición de Amores y Arte de Ajedrez (Repetition of Love and the Art of Playing Chess) by Spanish churchman Luis Ramirez de Lucena was published in Salamanca in 1497. Lucena and later masters like Portuguese Pedro Damiano, Italians Giovanni Leonardo Di Bona, Giulio Cesare Polerio and Gioachino Greco or Spanish bishop Ruy López de Segura developed elements of openings and started to analyze simple endgames.

In the eighteenth century the center of European chess life moved from the Southern European countries to France. The two most important French masters were François-André Danican Philidor, a musician by profession, who discovered the importance of pawns for chess strategy, and later Louis-Charles Mahé de La Bourdonnais who won a famous series of matches with the Irish master Alexander McDonnell in 1834. Centers of chess life in this period were coffee houses in big European cities like Café de la Régence in Paris and Simpson's Divan in London.

As the nineteenth century progressed, chess organization developed quickly. Many chess clubs, chess books and chess journals appeared. There were correspondence matches between cities; for example the London Chess Club played against the Edinburgh Chess Club in 1824. Chess problems became a regular part of nineteenth century newspapers; Bernhard Horwitz, Josef Kling and Samuel Loyd composed some of the most influential problems. In 1843, von der Lasa published his and Bilguer's Handbuch des Schachspiels (Handbook of Chess), the first comprehensive manual of chess theory.

Birth of a sport (1850–1945)

The first modern chess tournament was held in London in 1851 and won, surprisingly, by German Adolf Anderssen, relatively unknown at the time. Anderssen was hailed as the leading chess master and his brilliant, energetic — but from today's viewpoint strategically shallow — attacking style became typical for the time. Sparkling games like Anderssen's Immortal game or Morphy's Opera game were regarded as the highest possible summit of the chess art.

Deeper insight into the nature of chess came with two younger players. American Paul Morphy, an extraordinary chess prodigy, won against all important competitors, including Anderssen, during his short chess career between 1857 and 1863. Morphy's success stemmed from a combination of brilliant attacks and sound strategy; he intuitively knew how to prepare attacks. Prague-born Wilhelm Steinitz later described how to avoid weaknesses in one's own position and how to create and exploit such weaknesses in the opponent's position. In addition to his theoretical achievements, Steinitz founded an important tradition: his triumph over the leading German master Johannes Zukertort in 1886 is regarded as the first official World Chess Championship. Steinitz lost his crown in 1894 to a much younger German mathematician Emanuel Lasker, who maintained this title for 27 years, the longest tenure of all World Champions.

It took a prodigy from Cuba, José Raúl Capablanca (World champion 1921–27), who loved simple positions and endgames, to end the German-speaking dominance in chess; he was undefeated in tournament play for eight years until 1924. His successor was Russian-French Alexander Alekhine, a strong attacking player, who died as the World champion in 1946, having briefly lost the title to Dutch player Max Euwe in 1935 and regaining it two years later.

Between the world wars, chess was revolutionized by the new theoretical school of so-called hypermodernists like Aron Nimzowitsch and Richard Réti. They advocated controlling the center of the board with distant pieces rather than with pawns, inviting opponents to occupy the center with pawns which become objects of attack.

Since the end of 19th century, the number of annually held master tournaments and matches quickly grew. Some sources state that in 1914 the title of chess grandmaster was first formally conferred by Tsar Nicholas II of Russia to Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Tarrasch and Marshall, but this is a disputed claim. This tradition was continued by the World Chess Federation (FIDE), founded in 1924 in Paris. In 1927, Women's World Chess Championship was established; the first to hold it was Czech-English master Vera Menchik.

Post-war era (1945 and later)

After the death of Alekhine, a new World Champion was sought in a tournament of elite players ruled by FIDE, who have, since then, controlled the title. The winner of the 1948 tournament, Russian Mikhail Botvinnik, started an era of Soviet dominance in the chess world. Until the end of the Soviet Union, there was only one non-Soviet champion, American Bobby Fischer (champion 1972–1975).

In the previous informal system, the World Champion decided which challenger he would play for the title and the challenger was forced to seek sponsors for the match. FIDE set up a new system of qualifying tournaments and matches. The world's strongest players were seeded into "Interzonal tournaments", where they were joined by players who had qualified from "Zonal tournaments". The leading finishers in these Interzonals would go on the "Candidates" stage, which was initially a tournament, later a series of knock-out matches. The winner of the Candidates would then play the reigning champion for the title. A champion defeated in a match had a right to play a rematch a year later. This system worked on a three-year cycle.

Botvinnik participated in championship matches over a period of fifteen years. He won the world championship tournament in 1948 and retained the title in tied matches in 1951 and 1954. In 1957, he lost to Vasily Smyslov, but regained the title in a rematch in 1958. In 1960, he lost the title to the Latvian prodigy Mikhail Tal, an accomplished tactician and attacking player. Botvinnik again regained the title in a rematch in 1961.

Following the 1961 event, FIDE abolished the automatic right of a deposed champion to a rematch, and the next champion, Armenian Tigran Petrosian, a genius of defense and strong positional player, was able to hold the title for two cycles, 1963–1969. His successor, Boris Spassky from Russia (1969–1972), was a player able to win in both positional and sharp tactical style.

The next championship, the so-called Match of the Century, saw the first non-Soviet challenger since World War II, American Bobby Fischer, who defeated his Candidates opponents by unheard-of margins and clearly won the world championship match. In 1975, however, Fischer refused to defend his title against Soviet Anatoly Karpov when FIDE refused to meet his demands, and Karpov obtained the title by default. Karpov defended his title twice against Viktor Korchnoi and dominated the 1970s and early 1980s with a string of tournament successes.

Karpov's reign finally ended in 1985 at the hands of another Russian player, Garry Kasparov. Kasparov and Karpov contested five world title matches between 1984 and 1990; Karpov never won his title back.

In 1993, Garry Kasparov and Nigel Short broke with FIDE to organize their own match for the title and formed a competing Professional Chess Association (PCA). From then until 2006, there were two simultaneous World Champions and World Championships: the PCA or Classical champion extending the Steinitzian tradition in which the current champion plays a challenger in a series of many games; the other following FIDE's new format of many players competing in a tournament to determine the champion. Kasparov lost his Classical title in 2000 to Vladimir Kramnik of Russia.

The FIDE World Chess Championship 2006 reunified the titles, when Kramnik beat the FIDE World Champion Veselin Topalov and became the undisputed World Chess Champion. In September 2007, Viswanathan Anand became the next champion by winning a championship tournament.

Place in culture

Pre-modern

In the Middle Ages and during the Renaissance, chess was a part of noble culture; it was used to teach war strategy and was dubbed the "King's Game". Gentlemen are "to be meanly seene in the play at Chestes," says the overview at the beginning of Baldassare Castiglione's The Book of the Courtier (1528, English 1561 by Sir Thomas Hoby), but chess should not be a gentleman's main passion. Castiglione explains it further:

And what say you to the game at chestes? It is truely an honest kynde of enterteynmente and wittie, quoth Syr Friderick. But me think it hath a fault, whiche is, that a man may be to couning at it, for who ever will be excellent in the playe of chestes, I beleave he must beestowe much tyme about it, and applie it with so much study, that a man may assoone learne some noble scyence, or compase any other matter of importaunce, and yet in the ende in beestowing all that laboure, he knoweth no more but a game. Therfore in this I beleave there happeneth a very rare thing, namely, that the meane is more commendable, then the excellency.

Many of the elaborate chess sets used by the English aristocracy have been lost, but others survive, such as the Lewis chessmen.

At the same time, chess was often used as a basis of sermons on morality. An example is Liber de moribus hominum et officiis nobilium sive super ludo scacchorum ('Book of the customs of men and the duties of nobles or the Book of Chess'), written by an Italian Dominican monk Jacobus de Cessolis circa 1300. The popular work was translated into many other languages (first printed edition at Utrecht in 1473) and was the basis for William Caxton's The Game and Playe of the Chesse (1474), one of the first books printed in English. Different chess pieces were used as metaphors for different classes of people, and human duties were derived from the rules of the game or from visual properties of the chess pieces.

The knyght ought to be made alle armed upon an hors in suche wyse that he haue an helme on his heed and a spere in his ryght hande/ and coueryd wyth his sheld/ a swerde and a mace on his lyft syde/ Cladd wyth an hawberk and plates to fore his breste/ legge harnoys on his legges/ Spores on his heelis on his handes his gauntelettes/ his hors well broken and taught and apte to bataylle and couerid with his armes/ whan the knyghtes ben maad they ben bayned or bathed/ that is the signe that they shold lede a newe lyf and newe maners/ also they wake alle the nyght in prayers and orysons vnto god that he wylle gyue hem grace that they may gete that thynge that they may not gete by nature/ The kynge or prynce gyrdeth a boute them a swerde in signe/ that they shold abyde and kepe hym of whom they take theyr dispenses and dignyte.

On the other side, political and religious authorities in many places forbade chess as frivolous or as a sort of gambling.

Known in the circles of clerics, students and merchants, chess entered into the popular culture of Middle Ages. An example is the 209th song of Carmina Burana from the thirteenth century, which starts with the names of chess pieces, Roch, pedites, regina…

Modern

To the Age of Enlightenment, chess appeared mainly for self-improvement. Benjamin Franklin, in his article "The Morals of Chess" (1750), wrote:

"The Game of Chess is not merely an idle amusement; several very valuable qualities of the mind, useful in the course of human life, are to be acquired and strengthened by it, so as to become habits ready on all occasions; for life is a kind of Chess, in which we have often points to gain, and competitors or adversaries to contend with, and in which there is a vast variety of good and ill events, that are, in some degree, the effect of prudence, or the want of it. By playing at Chess then, we may learn:

1st, Foresight, which looks a little into futurity, and considers the consequences that may attend an action…

2nd, Circumspection, which surveys the whole Chess-board, or scene of action: - the relation of the several Pieces, and their situations…

3rd, Caution, not to make our moves too hastily…"

With these or similar hopes, chess is taught to children in schools around the world today and used in armies to train minds of cadets and officers. Many schools hold chess clubs and there are many scholastic tournaments specifically for children. In addition, many countries have chess federations, such as the United States Chess Federation, that hold tournaments regularly in addition to FIDE.

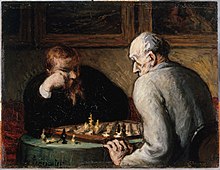

Moreover, chess is often depicted in the arts; significant works, where chess plays a key role, range from Thomas Middleton's A Game at Chess over Through the Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll to The Royal Game by Stefan Zweig or Vladimir Nabokov's The Defense. Chess is also important in films like Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal or Satyajit Ray's The Chess Players.

Chess is also present in the contemporary popular culture. For example, J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter plays "Wizard's Chess" while the characters of Star Trek prefer "Tri-Dimensional Chess" and the hero of Searching for Bobby Fischer struggles against adopting the aggressive and misanthropic views of a real chess Grandmaster.. Chess has also been used as the core theme of a musical, Chess, by Tim Rice, Björn Ulvaeus and Benny Andersson.

Notation for recording moves

Chess games and positions are recorded using a special notation, most often algebraic chess notation. Abbreviated (or short) algebraic notation generally records moves in the format abbreviation of the piece moved - file where it moved - rank where it moved, e.g. Qg5 means "queen moves to the g-file and 5th rank (that is, to the square g5). If there are two pieces of the same type that can move to the same square, one more letter or number is added to indicate the file or rank from which the piece moved, e.g. Ngf3 means "knight from the g-file moves to the square f3". The letter P indicating a pawn is not used, so that e4 means "pawn moves to the square e4".

If the piece makes a capture, "x" is inserted before the destination square, e.g. Bxf3 means "bishop captures on f3". When a pawn makes a capture, the file from which the pawn departed is used in place of a piece initial, and ranks may be omitted if unambiguous. For example, exd5 (pawn on the e-file captures the piece on d5) or exd (pawn on e-file captures something on the d-file).

If a pawn moves to its last rank, achieving promotion, the piece chosen is indicated after the move,for example e1Q or e1=Q. Castling is indicated by the special notations 0-0 for kingside castling and 0-0-0 for queenside. A move which places the opponent's king in check usually has the notation "+" added. Checkmate can be indicated by "#" (occasionally "++", although this is sometimes used for a double check instead). At the end of the game, "1-0" means "White won", "0-1" means "Black won" and "½-½" indicates a draw.

Chess moves can be annotated with punctuation marks and other symbols. For example ! indicates a good move, !! an excellent move, ? a mistake, ?? a blunder, !? an interesting move that may not be best or ?! a dubious move, but not easily refuted.

For example, one variant of a simple trap known as the Scholar's mate, animated in the picture to the right, can be recorded:

- e4 e5

- Qh5?! Nc6

- Bc4 Nf6??

- Qxf7# 1-0

Chess composition

Richard RétiOstrauer Morgenzeitung 4 December 1921

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

One of the most famous chess studies ever. It seems impossible to catch the advanced black pawn, while the black king can easily stop the white pawn. The solution is diagonal advance, bringing the king to both pawns at the same time: 1. Kg7! h4 2. Kf6 Kb6 (or 2. …h3 3. Ke7 and the white king can support its pawn) 3. Ke5!! (now the white king comes just in time to his pawn, or catches the black one) 3. …h3 4. Kd6 draw.

Main article: Chess problemChess composition is the art of creating chess problems (these problems themselves are sometimes also called chess compositions). A person who creates such problems is known as a chess composer.

Most chess problems exhibit the following features:

- The position is composed, that is, it has not been taken from an actual game, but has been invented for the specific purpose of providing a problem.

- There is a specific stipulation, that is, a goal to be achieved; for example, to checkmate black within a specified number of moves.

- There is a theme (or combination of themes) that the problem has been composed to illustrate: chess problems typically instantiate particular ideas. Many of these themes have their own names, often by persons who used them first, for example Novotny or Lacny theme.

- The problem exhibits economy in its construction: no greater force is employed than that required to guarantee that the problem's intended solution is indeed a solution and that it is the problem's only solution.

- The problem has aesthetic value. Problems are experienced not only as puzzles but as objects of beauty. This is closely related to the fact that problems are organized to exhibit clear ideas in as economical a manner as possible.

There are many types of chess problems. The two most important are:

- Directmates: white to move first and checkmate black within a specified number of moves against any defense. These are often referred to as "mate in n" - for example "mate in three" (a three-mover).

- Studies: orthodox problems in which the stipulation is that white to play must win or draw. Almost all studies are endgame positions.

Chess composition is a distinct branch of chess sport, and tournaments (or tourneys) exist for both the composition and solving of chess problems.

Competitive play

Organization of competitions

Contemporary chess is an organized sport with structured international and national leagues, tournaments and congresses. Chess's international governing body is FIDE (Fédération Internationale des Échecs). Most countries have a national chess organization as well (such as the US Chess Federation and English Chess Federation), which in turn is a member of FIDE. FIDE is a member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), but the game of chess has never been part of the Olympic Games; chess does have its own Olympiad, held every two years as a team event. An estimated 605 million people worldwide know how to play chess, and 7.5 million are members of national chess federations, which exist in 160 countries worldwide. This makes chess one of the most popular sports worldwide.

The current World Chess Champion is Viswanathan Anand of India. The reigning Women's World Champion is Alexandra Kosteniuk from Russia. However, the world's highest rated female player, Judit Polgar, has never participated in the Women's World Chess Championship, instead preferring to compete with the leading men and maintaining a ranking among the top 20 male players.

Other competitions for individuals include the World Junior Chess Championship, the European Individual Chess Championship and the National Chess Championships. Invitation-only tournaments regularly attract the world's strongest players and these include Spain's Linares event, Monte Carlo's Melody Amber tournament, the Dortmund Sparkassen meeting, Sofia's M-tel Masters and Wijk aan Zee's Corus tournament.

Regular team chess events include the aforementioned Chess Olympiad and the European Team Championship. The 37th Chess Olympiad was held 2006 in Turin, Italy; Armenia won the gold in the unrestricted event, and Ukraine took the top medal for the women. The World Chess Solving Championship and World Correspondence Chess Championships are both team and individual events.

Besides these prestigious competitions, there are thousands of other chess tournaments, matches and festivals held around the world every year, which cater to players of all levels, from beginners to experts.

Titles and rankings

Main article: Chess titles

The best players can be awarded specific lifetime titles by the world chess organization FIDE:

- Grandmaster (shortened as GM, sometimes International Grandmaster or IGM is used) is awarded to world-class chess masters. Apart from World Champion, Grandmaster is the highest title a chess player can attain. Before FIDE will confer the title on a player, the player must have an Elo chess rating (see below) of at least 2500 at one time and three favorable results (called norms) in tournaments involving other Grandmasters, including some from countries other than the applicant's. There are also other milestones a player can achieve to attain the title, such as winning the World Junior Championship.

- International Master (shortened as IM). The conditions are similar to GM, but less demanding. The minimum rating for the IM title is 2400.

- FIDE Master (shortened as FM). The usual way for a player to qualify for the FIDE Master title is by achieving a FIDE Rating of 2300 or more.

- Candidate Master (shortened as CM). Similar to FM, but with a FIDE Rating of at least 2200.

All the titles are open to men and women. Separate women-only titles, such as Woman Grandmaster (WGM), are also available. Beginning with Nona Gaprindashvili in 1978, a number of women have earned the GM title, and most of the top ten women in 2006 hold the unrestricted GM title.

International titles are awarded to composers and solvers of chess problems, and to correspondence chess players (by the International Correspondence Chess Federation). Moreover, national chess organizations may also award titles, usually to the advanced players still under the level needed for international titles; an example is the Chess expert title used in the United States.

In order to rank players, FIDE, ICCF and national chess organizations use the Elo rating system developed by Arpad Elo. Elo is a statistical system based on assumption that the chess performance of each player in their games is a random variable. Arpad Elo thought of a player's true skill as the average of that player's performance random variable, and showed how to estimate the average from results of player's games. The US Chess Federation implemented Elo's suggestions in 1960, and the system quickly gained recognition as being both fairer and more accurate than older systems; it was adopted by FIDE in 1970.

The highest ever FIDE rating was 2851, which Garry Kasparov had on the July 1999 and January 2000 lists. In the most recent list (January 2008), the highest rated players are the current world champion Viswanathan Anand of India and the former one Vladimir Kramnik of Russia with a rating of 2799.

Mathematics and computers

Main articles: Computer chess and List of mathematicians who studied chess

The game structure and nature of Chess is related to several branches of Mathematical theory. Many combinatorical and topological problems connected to chess were known of for hundreds of years. In 1913, Ernst Zermelo used it as a basis for his theory of game strategies, which is considered as one of the predecessors of game theory.

The number of legal positions in chess is estimated to be between 10 and 10, with a game-tree complexity of approximately 10. The game-tree complexity of chess was first calculated by Claude Shannon as 10, a number known as the Shannon number. Typically an average position has thirty to forty possible moves, but there may be as few as zero (in the case of checkmate or stalemate) or as many as 218.

The most important mathematical challenge of chess is the development of algorithms which can play chess. The idea of creating a chess playing machine dates to the eighteenth century; around 1769, the chess playing automaton called The Turk became famous before being exposed as a hoax. Serious trials based on automatons, such as El Ajedrecista, were too complex and limited to be useful.

Since the advent of the digital computer in the 1950s, chess enthusiasts and computer engineers have built, with increasing degrees of seriousness and success, chess-playing machines and computer programs. The groundbreaking paper on computer chess, "Programming a Computer for Playing Chess", was published in 1950 by Shannon. He wrote:

The chess machine is an ideal one to start with, since: (1) the problem is sharply defined both in allowed operations (the moves) and in the ultimate goal (checkmate); (2) it is neither so simple as to be trivial nor too difficult for satisfactory solution; (3) chess is generally considered to require "thinking" for skillful play; a solution of this problem will force us either to admit the possibility of a mechanized thinking or to further restrict our concept of "thinking"; (4) the discrete structure of chess fits well into the digital nature of modern computers.

The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) held the first major chess tournament for computers, the North American Computer Chess Championship, in September 1970. CHESS 3.0, a chess program from Northwestern University, won the championship. Nowadays chess programs compete in the World Computer Chess Championship, held annually since 1974. At first considered only a curiosity, the best chess playing programs, for example Rybka or Hydra, have become extremely strong. Garry Kasparov, then ranked number one in the world, lost a match against IBM's Deep Blue in 1997. Nevertheless, from the point of view of artificial intelligence, chess-playing programs are relatively simple: they essentially explore huge numbers of potential future moves by both players and apply an evaluation function to the resulting positions, an approach described as "brute force" because it relies on the sheer speed of the computer.

With huge databases of past games and high analytical ability, computers also help players to learn chess and prepare for matches. Additionally, Internet Chess Servers allow people to find and play opponents all over the world. The presence of computers and modern communication tools have also raised concerns regarding cheating during games, most notably the "bathroom controversy" during the 2006 World Championship.

Psychology

There is an extensive scientific literature on chess psychology. Alfred Binet and others showed that knowledge and verbal, rather than visuospatial, ability lies at the core of expertise. Adriaan de Groot, in his doctoral thesis, showed that chess masters can rapidly perceive the key features of a position. According to de Groot, this perception, made possible by years of practice and study, is more important than the sheer ability to anticipate moves. De Groot also showed that chess masters can memorize positions shown for a few seconds almost perfectly. Memorization ability alone does not account for this skill, since masters and novices, when faced with random arrangements of chess pieces, had equivalent recall (about half a dozen positions in each case). Rather, it is the ability to recognize patterns, which are then memorized, which distinguished the skilled players from the novices. When the positions of the pieces were taken from an actual game, the masters had almost total positional recall.

More recent research has focused on the respective roles of knowledge and look-ahead search; brain imaging studies of chess masters and novices; blindfold chess; the role of personality and intelligence in chess skill, gender differences, and computational models of chess expertise. In addition, the role of practice and talent in the development of chess and other domains of expertise has led to a lot of research recently. Ericsson and colleagues have argued that deliberate practice is sufficient for reaching high levels of expertise, like master in chess. However, more recent research indicates that factors other than practice are important. For example, Gobet and colleagues have shown that stronger players start playing chess earlier, that they are more likely to be left-handed, and that they are more likely to be born in late winter and early spring.

There are also some attempts to use the game of chess as mental training.

Variants

Main article: Chess variant

Chess variants are forms of chess where the game is played with a different board, special fairy pieces or different rules. There are more than two thousand published chess variants, the most popular being xiangqi in China and shogi in Japan.

Chess variants can be divided into:

- Direct predecessors of chess, chaturanga and shatranj.

- Traditional national or regional chess variants like xiangqi, shogi, janggi and makruk, which share common predecessors with Western chess.

- Modern variants of chess, such as Chess960, where the initial position is selected randomly before each game. This random positioning makes it more difficult to prepare the opening play in advance.

See also

- List of chess topics

- List of chess world championship matches

- List of chess players

- List of famous chess games

- List of strong chess tournaments

- Chess terminology

- Chess Olympiad

- Chess around the world

- Chess in early literature

- Comparing top chess players throughout history

Notes

- Murray, H.J.R. (1913). A History of Chess. Benjamin Press (originally published by Oxford University Press). ISBN 0-936317-01-9.

- "The rules of chess". Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- World Chess Federation. FIDE Laws of Chess. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- "Tarrasch vs Euwe on chessgames.com". (Java needed)

- Harding (2003), p. 1–7

- Harding (2003), p. 138ff

- Harding (2003), p. 8ff

- Harding (2003), p. 70ff

- Collins, Sam (2005). Understanding the Chess Openings. Gambit Publications. ISBN 1-904600-28-X.

- Tarrasch, Siegbert (1987). The Game of Chess. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-25447-X.

- Harding (2003), p. 32–151

- Harding (2003), p. 187ff

- Murray, H.J.R. (1913). A History of Chess. Benjamin Press (originally published by Oxford University Press). ISBN 0-936317-01-9.

- ^ Hooper and Whyld, 144-45 (first edition)

- Li, David H. (1998). The Genealogy of Chess. Premier Pub. Co. ISBN 0-9637852-2-2.

- Davidson (1981), p. 13–17

- ^ Calvo, Ricardo. Valencia Spain: The Cradle of European Chess. Retrieved 10 December 2006

- An analysis from the feminist perspective: Weissberger, Barbara F. (2004). Isabel Rules: constructing queenship, wielding power. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-4164-1. P. 152ff

- See History of the stalemate rule.

- Louis Charles Mahe De La Bourdonnai. Chessgames.com. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- Metzner, Paul (1998). Crescendo of the Virtuoso: Spectacle, Skill, and Self-Promotion in Paris during the Age of Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20684-3. Online version

- Bird, Henry Edward. Chess History and Reminiscences. Retrieved 10 December 2006

- London Chess Club. Chessgames.com. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- World Title Matches and Tournaments - Chess history. worldchessnetwork.com

- Burgess, Graham, Nunn, John and Emms, John (1998). The Mammoth Book of the World's Greatest Chess Games. Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-7867-0587-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link), p. 14. - Shibut, Macon (2004). Paul Morphy and the Evolution of Chess Theory. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43574-1.

- Steinitz, William and Landsberger, Kurt (2002). The Steinitz Papers: Letters and Documents of the First World Chess Champion. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1193-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kasparov (1983a)

- Kasparov 1983b

- Fine (1952)

- This is stated for example in The Encyclopaedia of Chess (1970, p.223) by Anne Sunnucks, but this is also disputed by Edward Winter (chess historian) in his Chess Notes 5144 and 5152.

- Menchik at ChessGames.com. Retrieved 11 December 2006

- Kasparov 2003b, 2004a, 2004b, 2006

- ^ "Chess History". Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- Kasparov 2003b, 2004a

- Kasparov 2003a, 2006

- Keene, Raymond (1993). Gary Kasparov's Best Games. B. T. Batsford Ltd. ISBN 0-7134-7296-0., p. 16.

- Kramnik at ChessGames.com. Retrieved 13 December 2006

- "Viswanathan Anand regains world chess title". Reuters. 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Vale, Malcolm (2001). The Princely Court: Medieval Courts and Culture in North-West Europe, 1270–1380. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926993-9. Pp. 170–199

- The Second Book of the Courtier. Translated by Sir Thomas Hoby (1561) as edited by Walter Raleigh for David Nutt, Publisher, London, 1900. Online at University of Oregon. Retrieved 21 Feb 2008

- The Introduction of Printing into England and the Early Work of the Press: The First Book printed in English, from The Cambridge History of English and American Literature, Vol II. (1907) Online at bartleby.com. Retrieved 12 December 2006

- Adams, Jenny (2006). Power Play: The Literature and Politics of Chess in the Late Middle Ages. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3944-X.

- Caxton, William. The Game and Playe of the Chesse. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 9 December 2006

- Camina Burana. Bibliotheca Augustana. Retrieved 2 November 2006

- Franklin, Benjamin. The Morals of Chess. metajedrez.com.ar. Retrieved 2 December 2006

- National Scholastic Chess Foundation. Retrieved 10 December 2006

- Ranjan Das: Shatranj Ke Khiladi (1977), analysis at upperstall.com. Retrieved 21 Feb 2008

- Eamonn O'Neill: Template:PDFlink Retrieved 20 December 2007

- FIDE Laws of Chess, App. E. Retrieved 11 December 2006

- "Learn Chess Notation". Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- Howard, Kenneth S (1961). How to Solve Chess Problems. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-20748-X.

- Chess in the Olympics. Retrieved 19 December 2006

- [http://www.usatoday.com/sports/2007-09-30-anand_N.htm India's Anand seizes chess title

- World Chess Federation. FIDE Handbook: Chess Rules. 1.0. Requirements for the titles designated in 0.31. Retrieved 9 December 2006.

- Current FIDE lists of top players with their titles are online at fide.com. Retrieved 11 December 2006

- FIDE Handbook The working of the FIDE Rating System. Retrieved 13 December 2006

- European Chess Union. Retrieved 11 December 2006

- "FIDE Top 100 Players".

- Zermelo, Ernst (1913), Uber eine Anwendung der Mengenlehre auf die Theorie des Schachspiels, Proceedings of the Fifth International Congress of Mathematicians 2, 501-4. Cited from Eichhorn, Christoph: Der Beginn der Formalen Spieltheorie: Zermelo (1913), http://www.mathematik.uni-muenchen.de/~spielth/artikel/Zermelo.pdf Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- Chess. Mathworld.Wolfram.com. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- Levitt, Gerald M. (2000). The Turk, chess automaton. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-0778-6.

- Shannon, Claude E. XXII. Programming a Computer for Playing Chess. Philosophical Magazine, Ser.7, Vol. 41, No. 314 - March 1950. Available online at Template:PDFlink Retrieved 6 December 2006.

- Feng-Hsiung Hsu (2002). Behind Deep Blue: Building the Computer that Defeated the World Chess Champion. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09065-3.; Deep Blue — Kasparov Match. research.ibm.com. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- Gobet, Fernand, de Voogt, Alex, & Retschitzki, Jean (2004). Moves in mind: The psychology of board games. Psychology Press. ISBN 1-84169-336-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Holding, Dennis (1985). The psychology of chess skill. Erlbaum. ISBN 978-0-89859-575-8.

- Saariluoma, Pertti (1995). Chess players' thinking: A cognitive psychological approach. Routledge. ISBN 0415120799-1-DBS.

- Binet, A. (1894). Psychologie des grands calculateurs et joueurs d'échecs. Paris: Hachette.

- Working memory in chess (PDF)

- De Groot A.D. (1965). Thought and choice in chess (first Dutch edition in 1946). The Hague: Mouton Publishers.

- Richards J. Heuer, Jr. Psychology of Intelligence Analysis Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency 1999 (see ).

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. Th., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). Template:PDFlink Psychological Review, 100, 363–406. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- Gobet, F. & Chassy, P. (in press). Template:PDFlink Journal of Biosocial Science.

Gobet, F. & Campitelli, G. (2007). Template:PDFlink Developmental Psychology, 43, 159–172. Both retrieved 15 July 2007. - Pritchard, D. (2000). Popular Chess Variants. Batsford Chess Books. ISBN 0-7134-8578-7.

- Pritchard, D. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Chess Variants. Games & Puzzles Publications. ISBN 0-9524142-0-1.

- van Reem, Eeric. The birth of Fischer Random Chess. chessvariants.com, 24 July 2001. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

References

- Davidson, Henry A. (1949, 1981). A Short History of Chess. McKay. ISBN 0-679-14550-8.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Harding, Tim (2003). Better Chess for Average Players. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-29029-8.

- Hooper, David and Whyld, Kenneth (1992). The Oxford Companion to Chess, Second edition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866164-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Reprint: (1996) ISBN 0-19-280049-3 - Kasparov, Garry (2003a). My Great Predecessors, part I. Everyman Chess. ISBN 1-85744-330-6.

- Kasparov, Garry (2003b). My Great Predecessors, part II. Everyman Chess. ISBN 1-85744-342-X.

- Kasparov, Garry (2004a). My Great Predecessors, part III. Everyman Chess. ISBN 1-85744-371-3.

- Kasparov, Garry (2004b). My Great Predecessors, part IV. Everyman Chess. ISBN 1-85744-395-0.

- Kasparov, Garry (2006). My Great Predecessors, part V. Everyman Chess. ISBN 1-85744-404-3.

- Wilkinson, Charles K. (1943). "Chessmen and Chess". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series, Vol. 1, No. 9: 271–279. doi:10.2307/3257111.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Fine, Reuben (1983). The World's Great Chess Games. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-24512-8.

- Gobet, Fernand, de Voogt, Alex, & Retschitzki, Jean (2004). Moves in mind: The psychology of board games. Psychology Press. ISBN 1-84169-336-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mason, James (1947). The Art of Chess. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-20463-4. (see the included supplement, "How Do You Play Chess")

- Rizzitano, James (2004). Understanding Your Chess. Gambit Publications. ISBN 1-904600-07-7.

- Tarrasch, Siegbert (1994). The Game of Chess. Algebraic Edition. Hays Publishing. ISBN 1-880673-94-0.

External links

Listen to this article(2 parts, 1 hour and 13 minutes)

- International organizations

- News

- Other

- ChessGames.com - online chess database and community

- ChessLive - online database

- Mathworld - chess and mathematics

- Jmrw.com - chess and art

| Chess | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outline | |||||||||

| Equipment | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| Rules | |||||||||

| Terms | |||||||||

| Tactics | |||||||||

| Strategy | |||||||||

| Openings |

| ||||||||

| Endgames | |||||||||

| Tournaments |

| ||||||||

| Art and media | |||||||||

| Related | |||||||||

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: