This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Wallamoose (talk | contribs) at 00:45, 7 October 2008 (→Allegations of sexual harassment: fixed refs). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:45, 7 October 2008 by Wallamoose (talk | contribs) (→Allegations of sexual harassment: fixed refs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Clarence Thomas | |

|---|---|

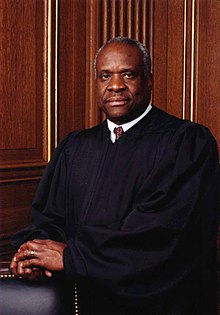

Clarence Thomas Clarence Thomas | |

| Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court | |

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office October 19 1991 | |

| Nominated by | George H. W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Thurgood Marshall |

| Personal details | |

| Spouse(s) | Kate Ambush Thomas (div.) Virginia Lamp Thomas |

| Alma mater | College of the Holy Cross Yale University |

Clarence Thomas (born June 23,1948) is an American jurist. He has been serving as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States since 1991, the second African American to serve on the nation's highest court (after Justice Thurgood Marshall). Appointed by President George H. W. Bush, Thomas's career in the Supreme Court has seen him take a conservative approach to cases while adhering to the principle of originalism.

Early life

Clarence Thomas was born in Pin Point, Georgia in a small Gullah-speaking community outside Savannah. He learned to speak the Gullah languages as a child, but purposely sought to downplay the language in favor of assimilation into his English speaking class. His father left his family when he was only two years old, leaving his mother Leola Anderson to take care of the family. When Thomas was seven they went to live with his mother's father, Myers Anderson, in Savannah. He had a fuel oil business that also sold ice; Thomas often helped him make deliveries.

His grandfather believed in hard work and self-reliance and would counsel him to "never let the sun catch you in bed in the morning." In 1975, when Thomas read Race and Economics by economist Thomas Sowell, he found an intellectual foundation for this philosophy. The book criticized social reforms by government and instead argued for individual action to overcome circumstances and adversity. He was also influenced by Ayn Rand's bestselling book The Fountainhead, and would later require his staffers to watch the 1949 film version. Raised Roman Catholic (he later attended an Episcopal church with his wife, but returned to the Catholic Church in the late 1990s), Thomas considered entering the priesthood, attending St. John Vianney's Minor Seminary on the Isle of Hope near Savannah and, briefly, Conception Seminary College, a Roman Catholic seminary in Missouri. Thomas told interviewers that he left the seminary (and the call for priesthood) after overhearing a student say, in response to the news that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had been shot, "Good, I hope the SOB dies."

At the College of the Holy Cross he helped found the Black Student Union and graduated in 1971 with an A.B., cum laude in English. He then attended Yale Law School from which he received a Juris Doctor (J.D.) degree in 1974. To Dennis Prager, Judge Thomas has stated his opinion that, in his early career, his Yale law degree was not taken seriously by law firms to which he applied, who assumed that it was obtained because of affirmative action policies.

Thomas has one child, Jamal Adeen, from his first marriage. This marriage, to Kathy Grace Ambush, lasted from 1971 until their 1984 divorce. Thomas married Virginia Lamp in 1987.

Since joining the Supreme Court, Thomas requested an annulment of his first marriage from the Roman Catholic Church, which was granted by the Tribunal of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Arlington. He was reconciled to the Church in the mid-1990s and remains a practicing Catholic.

In 1994, Thomas performed, at his home, the wedding ceremony for radio host Rush Limbaugh's third marriage, to Marta Fitzgerald.

As his wife grew up in Nebraska and attended college at the University of Nebraska, Thomas is an avid Nebraska Cornhuskers fan who attends Husker football games, and in 2007 met with the 2006 National Championship Husker Volleyball team, telling them he bled Husker red.

Career

Early career

From 1974 to 1977, Thomas was an Assistant Attorney General of Missouri under then State Attorney General John Danforth. When Danforth was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1976 to 1979, Thomas left to become an attorney with Monsanto in St. Louis, Missouri. He returned to work for Danforth from 1979 to 1981 as a Legislative Assistant. Both men shared a common bond in that both had studied to be ordained (although Thomas was Roman Catholic and Danforth was ordained Episcopalian). Danforth was to be instrumental in championing Thomas for the Supreme Court.

In 1981, he joined the Reagan administration. From 1981 to 1982, he served as Assistant Secretary of Education for the Office of Civil Rights in the U.S. Department of Education. From 1982 to 1990 he was Chairman of the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission ("EEOC").

In 1990, President George H. W. Bush appointed Thomas to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

Supreme Court appointment

Main article: Clarence Thomas Supreme Court nominationOn July 1, 1991 President George H. W. Bush nominated Thomas to replace Thurgood Marshall who had recently announced his retirement. Marshall had been the only African American justice on the court. The selection of Thomas preserved the existing racial composition of the court, but it was seen as likely to move the ideological balance to the right.

American Bar Association's (ABA) rating for Judge Thomas was split between "qualified" and "not qualified."

Organizations including the NAACP, the Urban League and the National Organization for Women opposed the appointment based on Thomas's criticism of affirmative action and suspicions that Thomas might not be a supporter of the Supreme Court judgment in Roe v. Wade. Under questioning during confirmation hearings, Thomas repeatedly asserted that he had not formulated a position on the Roe decision.

Some of the public statements of Thomas's opponents foreshadowed the confirmation fight that would occur. One such statement came from activist Florence Kennedy at a July 1991 conference of the National Organization for Women in New York City. Making reference to the failure of Robert Bork's nomination, she said of Thomas, "We're going to 'bork' him."

| This article may be unbalanced toward certain viewpoints. Please improve the article by adding information on neglected viewpoints, or discuss the issue on the talk page. |

Allegations of sexual harassment

Toward the end of the confirmation hearings, information was leaked to the press from an FBI interview with Anita Hill, an attorney who had worked for Thomas at the Department of Education and the EEOC. On October 11, 1991, Hill was called to testify during the Senate confirmation hearing.

Hill said: "He spoke about acts that he had seen in pornographic films involving such matters as women having sex with animals and films showing group sex or rape scenes....On several occasions, Thomas told me graphically of his own sexual prowess....Thomas was drinking a Coke in his office, he got up from the table at which we were working, went over to his desk to get the Coke, looked at the can and asked, 'Who has put pubic hair on my Coke?'" Hill also indicated that Thomas made reference to the pornographic actor Long Dong Silver.

Diane Holt testified that in the years after Hill left for another job, she called a dozen times to speak with Thomas and once asked for his hotel information, suggesting they were on friendly terms. Anita Hill first denied and later admitted that the calls took place. Nancy Altman from the Department of Education testified that, "It is not credible that Clarence Thomas could have engaged in the kinds of behavior that Anita Hill alleges, without any of the women who he worked closest with -- dozens of us, we could spend days having women come up, his secretaries, his chief of staff, his other assistants, his colleagues -- without any of us having sensed, seen or heard something." Senator Specter said that "the testimony of Professor Hill in the morning was flat out perjury and that she specifically changed it in the afternoon when confronted with the possibility of being contradicted."

Hill was the only person to testify at the Senate hearings that Thomas had harassed her or engaged in inappropriate conduct. Angela Wright, who worked with Thomas at the EEOC before he fired her for impropriety, told staff of members of the Senate Judiciary Committee during an interview that Thomas had repeatedly made comments to her, much like those Hill says he made to her, including pressuring her for dates and commenting on her body. Wright said that Thomas made comments about her and other women's anatomy "quite often." Wright told several senators' staff that Clarence Thomas asked her the size of her breasts. Wright said that after she turned down Thomas for a date, Thomas began to express discontent with her work and eventually fired her. Rose Jourdain said that Wright had spoken to her about Thomas at the original time of the events, but never testified before the Senate committee. Jourdain said that Wright told her of "increasingly aggressive behavior" and Wright's becoming "increasingly upset and increasingly unnerved." Jourdain spoke of Thomas's comments on Wright's bra size and legs, and of how Thomas once "had the nerve" to come to Wright's home.

Another former Thomas assistant, Sukari Hardnett, made further damaging charges against Thoams. Although Hardnett made it clear she was not accusing Thomas of sexual harassment, she provided the Judiciary Committee with sworn testimony that "if you were young, black, female, reasonably attractive and worked directly for Clarence Thomas, you knew full well you were being inspected and auditioned as a female." Additionally, Ellen Wells, John W. Carr, Judge Susan Hoerchner, and Joel Paul testified that Hill had discussed Thomas's actions at the time she worked for Thomas and that she had characterized them as sexual harassment.

Jane Mayer and Jill Abramson, reporters for the Wall Street Journal, concluded in an investigative book on Thomas that “the preponderance of the evidence suggests” that Thomas lied under oath when he told the committee he had not harassed Hill. Mayer and Abramson say Senator Biden abdicated control of the Thomas confirmation hearings and did not call Angela Wright to the stand. According to Mayer and Abramson, four women traveled to Washington DC to corroborate Anita Hill’s claims.

According to Mayer and Abramson, soon after Thomas was sworn in, three reporters for The Washington Post “burst into the newsroom almost simultaneously with information confirming that Thomas’ involvement with pornography far exceeded what the public had been led to believe.” These reporters had eyewitness testimony and video rental records showing Thomas’ interest in and use of pornography. However, because Thomas was already sworn in by the time the video store evidence emerged, The Washington Post dropped the story.

Diane Holt testified that in the years after Hill left for another job, she called a dozen times to speak with Thomas and once asked for his hotel information, suggesting they were on friendly terms. Anita Hill first denied and later admitted that the calls took place. Nancy Altman from the Department of Education testified that, "It is not credible that Clarence Thomas could have engaged in the kinds of behavior that Anita Hill alleges, without any of the women who he worked closest with -- dozens of us, we could spend days having women come up, his secretaries, his chief of staff, his other assistants, his colleagues -- without any of us having sensed, seen or heard something." http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/senate/judiciary/sh102-1084pt4/browse.html Senator Specter said that "the testimony of Professor Hill in the morning was flat out perjury and that she specifically changed it in the afternoon when confronted with the possibility of being contradicted." http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/senate/judiciary/sh102-1084pt4/browse.html

Thomas denied all allegations of sexual harassment and sexual impropriety by Hill and the others. Of the committee's investigation of the accusations, Thomas said: "This is not an opportunity to talk about difficult matters privately or in a closed environment. This is a circus. It's a national disgrace. And from my standpoint, as a black American, it is a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves, to do for themselves, to have different ideas, and it is a message that unless you kowtow to an old order, this is what will happen to you. You will be lynched, destroyed, caricatured by a committee of the U.S. Senate rather than hung from a tree."

After extensive debate, the committee sent the nomination to the full Senate without a recommendation either way. Thomas was confirmed by the Senate with a 52-48 vote on October 15, 1991, the narrowest margin for approval in more than a century. The final floor vote was not along strictly party lines: 41 Republicans and 11 Democrats voted to confirm while 46 Democrats and two Republicans (Jim Jeffords (R-VT) and Bob Packwood (R-OR)) voted to reject the nomination.

On October 23, 1991, Thomas took his seat as the 106th Associate Justice of the Supreme Court.

Early Days on the Court

Though Thomas was immediately welcomed by most Justices, including Marshall, whom he was replacing, law clerks of the more liberal justices viewed Thomas with ill-disguised contempt, questioning his qualifications and intellectual heft. According to Jan Crawford Greenburg, Justice Blackmun allowed his clerks to refer to Christopher Landau, a Thomas clerk, as "Justice," because they saw him as the one really "running the show." Greenburg called this "a rude and glaring breach of protocol." Greenburg says that pundits' portrayal of Thomas as Scalia's understudy was grossly inaccurate - she says that from early on, it was more often Scalia changing his mind to agree with Thomas, rather than the other way around. However, Greenburg points out that the extremity of Thomas's views pushed Justices Souter, O'Connor, and Kennedy away.

Judicial philosophy

Clarence Thomas is a conservative who acknowledges having some "libertarian leanings." Thomas is often described as an originalist. Although he has been compared to Antonin Scalia, he is less devoted to precedent than Scalia, who told Thomas' biographer that Thomas "doesn't believe in stare decisis, period. If a constitutional line of authority is wrong, he would say let's get it right." In Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow and Cutter v. Wilkinson, Thomas argued that the Establishment Clause was not incorporated to states by the Fourteenth Amendment, directly challenging the precedent Everson v. Board of Education. He has advocated the reversal of Roe v. Wade, joining the dissenting opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, and writing the concurrence in Gonzales v. Carhart. Thomas voted with Scalia 91 percent of the time during the court's 2006–07 session. He voted with Justice John Paul Stevens the least, only 36% of the time. Justice Thomas's forceful views have pushed moderates like Sandra Day O'Connor further to the left.

Commerce Clause and states' rights

Thomas consistently supports a strict interpretation of the Constitution's interstate commerce clause and supports limits on the power of federal government in favor of states' rights. In both United States v. Lopez and United States v. Morrison Thomas wrote a separate concurring opinion arguing for the original meaning of the commerce clause and criticizing the substantial effects formula. He wrote a sharply worded dissent in Gonzales v. Raich, a decision that permitted the federal government to arrest, prosecute, and imprison patients who were using medical marijuana. However, he previously authored United States v. Oakland Cannabis Buyers' Cooperative, an earlier case that also permitted the federal government to inspect medical marijuana dispensaries (the Oakland case dealt with the issue of medical necessity rather than federalism).

Capital punishment

Thomas was among the dissenters in both Atkins v. Virginia and Roper v. Simmons, which held that the Constitution prohibited the application of the death penalty to certain classes of persons. In Kansas v. Marsh, his opinion for the court indicated a belief that the Constitution affords states broad procedural latitude in imposing the death penalty provided they remain within the limits of Furman v. Georgia and Gregg v. Georgia, the 1976 case in which the court had reversed its 1972 ban on death sentences as long as states followed certain procedural guidelines.

Fourth Amendment

In the cases regarding the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures, Thomas often favors police over defendants, although not always—he was in the majority in Kyllo v. United States and wrote separately in Indianapolis v. Edmond the opinion that the Constitution does not allow random stops of drivers. His opinion for the court in Board of Education v. Earls upheld drug testing for students involved in extracurricular activities, and wrote again for the court in Samson v. California, permitting random searches on parolees. He dissented in the case Georgia v. Randolph, which prohibited warrantless searches that one resident approves and the other opposes, arguing that the case was controlled by the court's decision in Coolidge v. New Hampshire.

Free speech

Among Supreme Court Justices, Thomas is typically the second most likely to uphold free speech claims (he is tied with Souter). He has voted in favor of First Amendment claims in cases involving a wide variety of issues, including pornography, campaign contributions, political leafletting, religious speech, and commercial speech. On occasion, however, he disagrees with free speech claimants. For example, he dissented in Virginia v. Black, a case that struck down a Virginia statute that banned cross-burning, and authored ACLU v. Ashcroft, which referred the Child Online Protection Act back to District Court, where COPA was overturned. In addition, Thomas believes that students have limited free speech rights in public schools, a view he expressed in his concurrence in Morse v. Frederick. In that case, he argued that the precedent of Tinker v. Des Moines should be overruled.

Executive power

Thomas has argued that the executive branch has broad powers under the constitution. In Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, he was the only Justice who sided entirely with the government and the Fourth Circuit's ruling, arguing for the important security interests at stake and the President's broad war-making powers. He also was one of three justices who dissented in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, which held that the military commissions set up by the Bush administration to try detainees at Guantanamo Bay required explicit congressional authorization because they conflicted with both the Unified Military Code of Justice and "at least" Common Article 3 of the Geneva Convention...." Thomas argued that Hamdan is an illegal combatant and therefore not protected by the Geneva convention, and also agreed with Justice Scalia that the Court was "patently erroneous" in it's declaration of jurisdiction in this case.

Prisoners' Rights

In the Foucha case of Thomas's first term, Thomas dissented from the majority Supreme Court opinion removing from a mental institution a prisoner who had become sane. Thomas cast the issue as a states' rights matter.

In 1992's Hudson v. McMillan, Thomas said that injuries to a prisoner that involved a cracked lip, broken dental plate, loosened teeth, and cuts and bruises (all from what Thomas said was admittedly criminal police brutality) "did not rise to the level" of cruel and unusual punishment. Thomas's vote, the only one against the prisoner and an early example of Thomas's willingness to be the sole dissenter, would have rejected the prisoner's lawsuit had it been the majority view (Scalia later joined the opinion).

In 1992's Doggett v. United States, Thomas wrote a dissenting opinion for himself and Rehnquist to uphold the conviction of a man who was indicted on a drug charge, but then not arrested for almost nine years. Thomas wrote that dismissing the conviction "invites the Nation's judges to indulge in ad hoc and result-driven second guessing of the government's investigatory efforts. Our Constitution neither contemplates nor tolerates such a role."

Approach to oral arguments

Thomas is well-known for listening rather than asking questions during oral arguments of the Court. He has offered several reasons for this, including that he developed a habit of listening as a young man. Thomas comes from the Gullah/Geechee cultural region of coastal Georgia and is a member of this distinct African American ethnic group; he grew up speaking the Gullah language, which is a hybrid of English and various West African languages. Later in life, Thomas began to acquire an enthusiasm for his heritage, writing about it in the December 14 2000 issue of The New York Times:

- "When I was 16, I was sitting as the only black kid in my class, and I had grown up speaking a kind of a dialect. It's called Geechee. Some people call it now, and people praise it now. But they used to make fun of us back then. It's not standard English. When I transferred to an all-white school at a young age, I was self-conscious, like we all are... So I...just started developing the habit of listening."

However, Jeffrey Toobin in The Nine calls into question Thomas's explanation, showing that Thomas knew how to speak English well from an early age, because he lived with his English-speaking grandfather from the age of six, attended only English-speaking parochial schools, and earned excellent school grades. The New York Times also casts doubt on Thomas's Gullah explanation.

Thomas has stated that he wishes to write a book about the Gullah culture.

Another theory, asserted by one set of Thomas biographers, is that he believes oral arguments are mostly unnecessary, and that the back-and-forth in oral arguments is often disrespectful to the attorneys trying to present their cases. (This view has been supported by Ann Scarlett, Professor at the Saint Louis University School of Law, who was one of his law clerks.) The same biographers also theorize Thomas is uncomfortable in the rapid pacing of oral argument discussions, the supposition being he prefers a more cerebral, quieter environment in which to carefully contemplate matters of constitutional law.

In comments in November 2007, Thomas proffered his position on the subject: "My colleagues should shut up!" he said to an audience at Hillsdale College in Michigan. He later explained, "I don't think that for judging, and for what we are doing, all those questions are necessary", and compared his profession to the medical arts: "Suppose you're undergoing something very serious like surgery and the doctors started a practice of conducting seminars while in the operating room, debating each other about certain procedures and whether or not this procedure is this way or that way. You really didn't go in there to have a debate about gall bladder surgery."

Though Thomas is silent during most arguments before the Supreme Court, he had, up until his 16th term, spoken a few times each term. During the oral argument for NASA v. FLRA, In Apprendi v. New Jersey (2000), Thomas raised an issue which would become important in the opinions ("the distinction... between an element of the offense and an enhancement factor"). In Capitol Square Review Board v. Pinette (1995), Virginia v. Black (2003), and Georgia v. Randolph (2006), Thomas presaged his eventual dissent with comments at oral argument.

Upon the conclusion of the 2006-2007 term of the Supreme Court, it was widely noted that Thomas had failed to utter a single word from the bench during the course of the entire term. In November 2007, in a tongue-in-cheek manner, the Law Blog of the Wall Street Journal initiated the "When-Will-Justice-Thomas-Ask-a-Question Watch", noting that the justice had not asked a single question during oral arguments since February 22, 2006. February 22, 2008, marked the two year anniversary of Thomas's last question during oral argument, a milestone which was noted by several media outlets, including CNN. Another reference to his silence was made in the Boston Legal episode The Court Supreme where Denny Crane made a bet regarding whether Alan Shore could get the fictional Justice Thomas to talk.

Bibliography

- Thomas, Clarence (2007). My Grandfather's Son: A Memoir, Harper, ISBN 0-06-056555-1.

References

| This section uses citations that link to broken or outdated sources. Please improve the article by addressing link rot or discuss this issue on the talk page. (January 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Clarence Thomas bio from Notable Names Database

- Pin Point on Flickr - Photo Sharing!

- The 2000 Election

- ^ Merida K, Fletcher M, "Supreme Discomfort", Washington Post Magazine, August 4, 2002. Accessed May 7, 2007.

- Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas visits Conception Seminary College

- Townhall.com::Talk Radio Online::Radio Show

- Washington Post

- Insight Scoop | The Ignatius Press Blog: Did Clarence Thomas just say he's not Catholic?

- The religion of Clarence Thomas, Supreme Court Justice

- NYT Chronicle Article, 5/30/94

- Columbus Telegram

- Rush Limbaugh, Rush Recounts His Trip to Lincoln, www.rushlimbaugh.com, September 17, 2007.

- New York Times

- It is routine for nominees, at all levels of the Federal judiciary, to refuse to discuss cases during their confirmation hearings that might come before them if they are confirmed. Clinton appointed Associate Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Steven Breyer both refused to discuss Roe before the Judiciary Committee, even though Ginsburg has worked for years for the ALCU defending it. Despite this nearly universal refusal of nominees to discuss hot button issues such as Roe, members of the Senate Judiciary Committee nearly always try to draw the nominee's view out during confirmation hearings.

- Wall Street Journal's Opinion Journal

- Opening Statement: Sexual Harassment Hearings Concerning Judge Clarence Thomas," Women's Speeches from Around the World.

- http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/senate/judiciary/sh102-1084pt4/411-413.pdf

- http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/senate/judiciary/sh102-1084pt4/browse.html

- http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/senate/judiciary/sh102-1084pt4/browse.html

- http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/senate/judiciary/sh102-1084pt4/browse.html

- http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/senate/judiciary/sh102-1084pt4/browse.html

- ^ "United States Senate, Transcript of Proceedings" (pdf). gpoaccess.gov. 1991-10-10. pp. pp. 442-511. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - The New York Times. "THE THOMAS NOMINATION; Excerpts From Judiciary Committee's Interview of Angela Wright." Oct. 4, 1991.

- The New York Times. "THE THOMAS NOMINATION; Excerpts From Judiciary Committee's Interview of Angela Wright." Oct. 4, 1991.

- ^ "United States Senate, Transcript of Proceedings" (pdf). gpoaccess.gov. 1991-10-10. pp. pp. 512–559. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/senate/judiciary/sh102-1084pt4/512-559.pdf

- http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/10/02/AR2007100201822.html

- http://www.fair.org/index.php?page=1896

- http://hnn.us/comments/121846.html

- HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SECOND CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON THE NOMINATION OF CLARENCE THOMAS TO BE ASSOCIATE JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

- ^ Lacayo, Richard (2001-06-24). "The Unheard Witnesses". TIME. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- Toobin, Jeffrey. The Nine. First Anchor Books Edition, September 2008. Page 39.

- Toobin, Jeffrey. The Nine. First Anchor Books Edition, September 2008. Pages 38-39.

- Toobin, Jeffrey. The Nine. First Anchor Books Edition, September 2008. Page 39.

- http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/senate/judiciary/sh102-1084pt4/411-413.pdf

- http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/senate/judiciary/sh102-1084pt4/browse.html

- Hearing of the Senate Judiciary Committee on the Nomination of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court, Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library, October 11, 1991.

- Hall, Kermit (ed), The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States, page 871, Oxford Press, 1992

- Packwood himself would later be forced to resign from the Senate in the face accusations of sexual harassment, abuse and assault by numerous former staffers and lobbyists.

- Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 112.

- Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Pages 112-113.

- Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 115.

- Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Pages 115-116.

- Kauffman B., "Clarence Thomas", Reason Magazine, November 1987, Accessed May 7, 2007.

- "A Big Question About Clarence Thomas", The Washington Post, October 14, 2004. Accessed May 7, 2007.

- Greenhouse, Linda."In Steps Big and Small, Supreme Court Moved Right", New York Times, July 1, 2007.

- Greenhouse, Linda. "In Steps Big and Small, Supreme Court, Moved Right", The New York Times, July 1, 2007.

- Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 166.

- Volokh, Eugene. How the Justices Voted in Free Speech Cases, 1994-2002, UCLA Law

- Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, Supreme Court Syllabus, pg. 4., point 4.

- Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 117.

- Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 117.

- Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 119.

- Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 119.

- Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 123.

- Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 123.

- Linguistics

- Jeffrey Toobin, The Nine. Page 106. 2007. Doubleday. ISBN 0385516401.

- http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/17/books/review/Patterson-t.html?_r=1&pagewanted=2&oref=slogin

- Gullah

- This information was related in a 2006 conversation with law student Daren Rich, when asked why Justice Thomas was often silent during oral arguments.

- Blog

- U.S. News & World Report

- New York Times

- 527 U.S. 229 (1999)

- 515 U.S. 753

- Law.com

- Wall Street Journal Law Blog

- CNN article on lack of questions for 2 years

Sources

- Brock, David (1994). The Real Anita Hill, Touchstone, ISBN 0-02-904656-4

- Brooks, Roy L. Structures of Judicial Decision Making from Legal Formalism to Critical Theory

- Carp, Dylan (1998, September). Out of Scalia's Shadow. Liberty.

- Edward Shills and Max Rheinstien, Max Weber on Law in Economy and Society

- Foskett, Ken (2004). Judging Thomas: The Life and Times of Clarence Thomas, William Morrow, ISBN 0-06-052721-8

- Lazarus, Edward (2005, Jan. 6). Will Clarence Thomas Be the Court's Next Chief Justice? FindLaw.

- Mayer, Jane, and Jill Abramson (1994). Strange Justice: The Selling of Clarence Thomas, Houghton Mifflin Company, ISBN 0-452-27499-0

- Onwuachi-Willig, Angela (2005). Just Another Brother on the SCT?: What Justice Clarence Thomas Teaches Us About the Influence of Racial Identity. Iowa Law Review, 90.

- Presser, Stephen B. (2005, Jan.-Feb.) Touting Thomas: The Truth about America's Most Maligned Justice. Legal Affairs.

- Thomas, Andrew Peyton (2001). Clarence Thomas: A Biography, Encounter Books, ISBN 1-893554-36-8

- Supreme Court official biography (PDF format)

- Supreme Discomfort

- An Outline of the Anita Hill and Clarence Thomas Controversy

- U.S. Supreme Court Multimedia

- Transcripts of Senate Judiciary Committee Hearing on the Nomination of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court

- A Conversation with Justice Thomas

- "So, Guy Walks Up to the Bar, and Scalia says..."

- The Justice Thomas Appreciation Page

External links

- Clarence Thomas Speaks Out BusinessWeek

- Entry on Clarence Thomas by John P. Vanzo in The New Georgia Encyclopedia

- 23 June 2007 59th Birthday Commemoration Article "Clarence Thomas . . . My Friend" by Ellis Washington in WorldNetDaily.com

- 20 October 2007 Book Review of his memoir Article "Justice Clarence Thomas' "My Grandfather's Son" by Ellis Washington in WorldNetDaily.com

- 2007 City Journal article on Thomas

- 2007 interview in BusinessWeek

- October 11, 1991 evening session of U.S. Supreme Court confirmation hearings.

- Clarence Thomas at the 2007 Annual National Lawyers Convention - November 2007

- Overview of Personal Memoir

- Biography of Clarence Thomas - Cornell Law School

- Washington Post article about Thomas

- Complete text, audio, video of Judge Thomas 'High Tech Lynching' statement to the Senate Judiciary Committeefrom AmericanRhetoric.com

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded byRobert Bork | Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit 1990-1991 |

Succeeded byJudith Ann Wilson Rogers |

| Preceded byThurgood Marshall | Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1991-present | |

| U.S. order of precedence (ceremonial) | ||

| Preceded byDavid Souter Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States |

United States order of precedence Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States |

Succeeded byRuth Bader Ginsburg Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States |

| Judicial opinions of Clarence Thomas | |

|---|---|

| U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit (March 6, 1990 – October 17, 1991); by calendar year | |

| Supreme Court of the United States (October 18, 1991 – present); by term | |

Template:Start U.S. Supreme Court composition Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1991-1993 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1993-1994 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1994-2005 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 2005-2006 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 2006-present Template:End U.S. Supreme Court composition

{{subst:#if:Thomas, Clarence|}}

[[Category:{{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1948}}

|| UNKNOWN | MISSING = Year of birth missing {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:LIVING}}||LIVING=(living people)}}

| #default = 1948 births

}}]] {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:LIVING}}

|| LIVING = | MISSING = | UNKNOWN = | #default =

}}

Categories:- Articles with broken or outdated citations from January 2008

- Living people

- LIVING deaths

- African American Catholics

- African American judges

- American Roman Catholics

- Anglican converts to Catholicism

- College of the Holy Cross alumni

- Federalist Society members

- Georgia (U.S. state) lawyers

- Gullah

- Judges of the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit

- People from Georgia (U.S. state)

- People from McLean, Virginia

- United States Supreme Court justices

- Yale Law School alumni

- African American memoirists

- African American conservatism