This is an old revision of this page, as edited by JFD (talk | contribs) at 16:21, 18 November 2008 (Undid revision 252577289 by 70.89.56.150 (talk)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:21, 18 November 2008 by JFD (talk | contribs) (Undid revision 252577289 by 70.89.56.150 (talk))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

Gunpowder was the first chemical explosive and the only one known until the invention of nitrocellulose, nitroglycerin, smokeless powder and TNT in the 19th century. However, prior to the invention of gunpowder, many incendiary and burning devices had been used, including Greek fire.

China

Further information: List of Chinese inventions and History of science and technology in China

The prevailing academic consensus is that gunpowder was discovered in the 9th century by Chinese alchemists searching for an elixir of immortality. The discovery of gunpowder was probably the product of centuries of alchemical experimentation. Saltpetre was known to the Chinese by the mid-1st century AD, and there is strong evidence of the use of saltpetre and sulfur in various largely medicinal combinations. A Chinese alchemical text from 492 noted that saltpeter gave off a purple flame when ignited, providing for the first time a practical and reliable means of distinguishing it from other inorganic salts, making it possible to evaluate and compare purification techniques.

The first reference to gunpowder is probably a passage in the Zhenyuan miaodao yaolüe (真元妙道要略), a Taoist text tentatively dated to the mid-800s:

Some have heated together sulfur, realgar, and saltpeter with honey; smoke and flames result, so that their hands and faces have been burnt, and even the whole house where they were working burned down.

The discovery of gunpowder in the 800's and the subsequent invention of firearms in the 1100s both coincided with long periods of disunity, during which there was some immediate use for infantry and siege weapons. The years 904–906 saw the use of incendiary projectiles called 'flying fires' (fei-huo). Needham (1986) argues that gunpowder was first used in warfare in China in 919 as a fuse for the ignition of another incendiary, Greek fire. The earliest depiction of a gunpowder weapon is a mid-10th century silk banner from Dunhuang that shows a fire lance, precursor of the gun. The earliest depiction of a gun is a sculpture from a cave in Sichuan dating to the 1100s of a figure carrying a vase-shaped bombard with flames and a cannonball coming out of it. The oldest gun ever discovered, dated to 1288, has a muzzle-bore diameter of 2.5 cm; the second oldest, dated to 1332, has a muzzle-bore diameter of 10.5 cm.

The earliest surviving recipes for gunpowder can be found in the Wujing Zongyao of 1044, which contains three: two for use in incendiary bombs to be thrown by siege engines (48.5% saltpetre, 25.5% sulfur, 21.5% others; 50% saltpetre, 25% sulfur, 6.5% charcoal and 18.75% others) and one intended as fuel for poisonous-smoke bombs (38.5% saltpetre, 19% sulfur, 6.4% charcoal and 35.85% others). Many early mixtures of Chinese gunpowder contained toxic substances such as mercury and arsenic compounds. Printed editions of this book were made from about 1488, and in 1608 a hand-copied edition was made.

The formulas in the Wujing zongyao range from 27 to 50 percent nitrate. Experimenting with different levels of saltpetre content eventually produced bombs, grenades, and mines, in addition to giving fire arrows a new lease on life. By the end of the 12th century, there were cast-iron grenades filled with gunpowder formulations capable of bursting through their metal containers. An agglomeration of 60% saltpetre, 20% sulfur, and 20% charcoal that dated to about the late 13th century was unearthed in the city of Xi'an. The 14th century Huolongjing contains gunpowder recipes with nitrate levels ranging from 12% to 91%, six of which approach the theoretical composition for maximal explosive force. Zhang (1986) argues that the use of gunpowder in artillery as an explosive (as opposed to merely an incendiary) was made possible by improvements in the refinement of sulfur from pyrite during the Song Dynasty.

As early as the 11th century, the government of the Song Dynasty was concerned that foreign enemies might break its monopoly on gunpowder technology. The Song Shi (History of the Song Dynasty) of 1345 records that, in 1067, the Song government prohibited the people of Hedong (modern-day Shanxi and Hebei) from selling to foreigners any form of sulfur or saltpetre. In 1076 the Song government went further, issuing a ban on all private commercial transactions involving saltpetre and sulfur, for fear that they would be sold across borders, and creating a government monopoly on their production and commercial distribution.

The origin of rocket propulsion is the 'ground-rat,' a type of firework whose use was recorded in 1264 when they frightened the Empress-Mother Kung Sheng at a feast held in her honor by her son the Emperor Lizong. The 14th-century text of the Huolongjing illustrates and describes a Chinese multistage rocket with booster rockets that, when burnt out, ignited a swarm of smaller rockets issuing forth from the front of the missile shaped like a dragon's head. Along with rockets, the Huolongjing also described explosive land mines and naval mines.

In 1260, the personal arsenal of Song Dynasty Prime Minister Zhao Nanchong caught fire and exploded, destroying several outlying houses and killing four of his prized pet tigers. The Gui Xin Za Zhi of 1295 records that a much bigger accident took place at Weiyang in 1280, at an arsenal used primarily for the storage of trebuchet-launched bombs:

Formerly the artisan positions were all held by Southerners (i.e., the Chinese). But they engaged in peculation, so they had to be dismissed, and all their jobs were given to Northerners (probably Mongols, or Chinese who had served them). Unfortunately, these men understood nothing of the handling of chemical substances. Suddenly, one day, while sulfur was being ground fine, it burst into flame, then the (stored) fire lances caught fire, and flashed hither and thither like frightened snakes. (At first) the workers thought it was funny, laughing and joking, but after a short time the fire got into the bomb store, and then there was a noise like a volcanic eruption and the howling of a storm at sea. The whole city was terrified, thinking that an army was approaching...Even at a distance of a hundred li, tiles shook and houses trembled...The disturbance lasted a whole day and night. After order had been restored, an inspection was made, and it was found that a hundred men of the guards had been blown to bits, beams and pillars had been cleft asunder or carried away by the force of the explosion to a distance of over ten li. The smooth ground was scooped into craters and trenches more than ten feet deep. Above two hundred families living in the neighborhood were victims of this unexpected disaster.

In the year 1259, the official Li Zengbo wrote in his Ko Zhai Za Gao, Xu Gao Hou that the city of Qingzhou was manufacturing one to two thousand strong iron-cased bomb shells a month, dispatching to Xiangyang and Yingzhou about ten to twenty thousand such bombs at a time. In the 13th century, the Mongols conquered China and with it the technology of gunpowder. The use of cannon and rockets became a feature of East-Asian warfare thereafter, as Song China's enemies captured valuable craftsmen and engineers and set them to the task of crafting comparable weapons. After 1279, most guns taken from the major cities were kept by the Mongols. In 1330s, a Mongol law prohibited all kinds of weapons' being in the hands of Chinese. However, it was restricted to civilians, who didn't usually carry weapons. An account of a 1359 battle near Hangzhou records that both the Ming Chinese and Mongol sides were equipped with cannon. The low, thick city walls of Beijing (started in 1406), were specifically designed to withstand a gunpowder-artillery attack, and the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) moved the capital from Nanjing to Beijing in 1421, because the hills around Nanjing were good locations for invaders to place artillery.

In the 13th century, contemporary documentation shows that gunpowder was beginning to spread from China to the rest of the world, starting with Europe and the Islamic world.

In the 1593 Siege of Pyongyang 40,000 Ming soldiers deployed a variety of cannons to bombard Japanese army. During the Japanese invasions of Korea 7-Year Battle in Korea (1591-1598), Chinese-Korean coalition and Japanese(They used looted Korean cannons) widely used artillery (muskets and cannons) in land and sea battles.

Islamic and Hindu worlds

Islamic world

The Arabs acquired knowledge of gunpowder some time after 1240, but before 1280, by which time Hasan al-Rammah had written, in Arabic, recipes for gunpowder, instructions for the purification of saltpeter, and descriptions of gunpowder incendiaries. However, because al-Rammah attributes his material to "his father and forefathers", al-Hassan harvcoltxt error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFal-Hassan (help) argues that gunpowder became prevalent in Syria and Egypt by "the end of the twelfth century or the beginning of the thirteenth".

C. F. Temler interprets Peter, Bishop of Leon, as reporting the use of cannon in Seville in 1248. Al-Hassan claims that "the first cannon in history" was used by the Mamluks against the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260; Khan states that it was invading Mongols who introduced gunpowder to the Islamic world and cites Mamluk antagonism towards early riflemen in their infantry as an example of how gunpowder weapons were not always met with open acceptance in the Middle East. Similarly, the refusal of their Qizilbash forces to use firearms contributed to the Safavid rout at Chaldiran in 1514.

Though the consensus is that gunpowder originated in China, others have suggested that gunpowder might possibly have been invented by the Arabs, by Roger Bacon, or by Berthold Schwarz. The general notion is that Arabic alchemy and chemistry did not know of saltpetre until the thirteenth century; however, Ahmad Y Hassan argues that Arabs were purifying saltpetre by the eleventh century and that the earliest known military application of saltpetre (known as barud in Arabic) in the Islamic world is described in an Arabic manuscript written some time before 1225.

According to Johnson harvcoltxt error: no target: CITEREFJohnson (help), the Arabs "had developed the first real gun, a bamboo tube reinforced with iron, which used a charge of black powder to fire an arrow" some time before 1300; however, according to Chase (2003:1), the Arabs only obtained firearms in the 1300s and all evidence points to Chinese origins.

Hasan al-Rammah included 107 gunpowder recipes in his al-furusiyyah wa al-manasib al-harbiyya (The Book of Military Horsemanship and Ingenious War Devices), 22 of which are for rockets. If one takes the median of 17 of these 22 compositions for rockets (75% nitrates, 9.06% sulphur and 15.94% carbon), it is almost identical with the reported ideal recipe (75% potassium nitrate, 10% sulphur, and 15% carbon).

Hasan al-Rammah also describes the purifying of saltpetre using the chemical processes of solution and crystallization. This was the first clear method for the purification of saltpetre. The earliest torpedo was also first described in 1270 by Hasan al-Rammah in The Book of Military Horsemanship and Ingenious War Devices, which illustrated a torpedo running with a rocket system filled with explosive materials and having three firing points.

India

See also: History of Indian Science and Technology and List of Indian inventionsGunpowder arrived in India by the mid-1300s, but could have been introduced by the Mongols perhaps as early as the mid-1200s.

It was written in the Tarikh-i Firishta (1606-1607) that the envoy of the Mongol ruler Hulegu Khan was presented with a dazzling pyrotechnics display upon his arrival in Delhi in 1258 AD. As a part of an embassy to India by Timurid leader Shah Rukh (1405-1447), 'Abd al-Razzaq mentioned naphtha-throwers mounted on elephants and a variety of pyrotechnics put on display. Firearms known as top-o-tufak also existed in the Vijayanagara Empire of India by as early as 1366 AD. From then on the employment of gunpowder warfare in India was prevalent, with events such as the siege of Belgaum in 1473 AD by the Sultan Muhammad Shah Bahmani.

In A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, James Riddick Partington describes Indian rockets, mines and other means of gunpowder warfare:

The Indian war rockets were formidable weapons before such rockets were used in Europe. They had bam-boo rods, a rocket-body lashed to the rod, and iron points. They were directed at the target and fired by lighting the fuse, but the trajectory was rather erratic. The use of mines and counter-mines with explosive charges of gunpowder is mentioned for the times of Akbar and Jahāngir.

By the 16th century, Indians were manufacturing a diverse variety of firearms; large guns in particular, became visible in Tanjore, Dacca, Bijapur and Murshidabad. Guns made of bronze were recovered from Calicut (1504) and Diu (1533). Gujarāt supplied Europe saltpeter for use in gunpowder warfare during the 17th century. Bengal and Mālwa participated in saltpeter production. The Dutch, French, Portuguese, and English used Chāpra as a center of saltpeter refining.

Fathullah Shirazi (c. 1582), a Persian-Indian polymath and mechanical engineer who worked for Akbar the Great in the Mughal Empire, invented the autocannon, the earliest multi-shot gun. As opposed to the polybolos and repeating crossbows used earlier in ancient Greece and China, respectively, Shirazi's rapid-firing gun had multiple gun barrels that fired hand cannons loaded with gunpowder.

In Encyclopedia Britannica (2008), Stephen Oliver Fought & John F. Guilmartin, Jr. describe the gunpowder technology in 18th century India:

Hyder Ali, prince of Mysore, developed war rockets with an important change: the use of metal cylinders to contain the combustion powder. Although the hammered soft iron he used was crude, the bursting strength of the container of black powder was much higher than the earlier paper construction. Thus a greater internal pressure was possible, with a resultant greater thrust of the propulsive jet. The rocket body was lashed with leather thongs to a long bamboo stick. Range was perhaps up to three-quarters of a mile (more than a kilometre). Although individually these rockets were not accurate, dispersion error became less important when large numbers were fired rapidly in mass attacks. They were particularly effective against cavalry and were hurled into the air, after lighting, or skimmed along the hard dry ground. Hyder Ali's son, Tippu Sultan, continued to develop and expand the use of rocket weapons, reportedly increasing the number of rocket troops from 1,200 to a corps of 5,000. In battles at Seringapatam in 1792 and 1799 these rockets were used with considerable effect against the British.

The news of the successful use of rockets spread through Europe. In England Sir William Congreve began to experiment privately. First, he experimented with a number of black-powder formulas and set down standard specifications of composition. He also standardized construction details and used improved production techniques. Also, his designs made it possible to choose either an explosive (ball charge) or incendiary warhead.

Europe

One theory of how gunpowder came to Europe is that it made its way along the Silk Road through the Middle East; another is that it was brought to Europe during the Mongol invasion in the first half of the 13th century, or during the subsequent diplomatic and military contacts (see Franco-Mongol alliance). William of Rubruck, an ambassador to the Mongols in 1254-1255, a personal friend of Roger Bacon, is also often designated as a possible intermediary in the transmission of gunpowder know-how between the East and the West.

The earliest European reference to gunpowder is found in Roger Bacon's Epistola de secretis operibus artiis et naturae from 1267. The oldest written recipes for gunpowder in Europe were recorded under the name Marcus Graecus or Mark the Greek between 1280 and 1300.

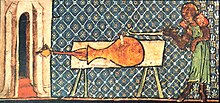

In 1326, the earliest known European picture of a gun appeared in a manuscript by Walter de Milemete. On February 11 of that same year, the Signoria of Florence appointed two officers to obtain canones de mettallo and ammunition for the town's defense. A reference from 1331 describes an attack mounted by two Germanic knights on Cividale del Friuli, using gunpowder weapons of some sort. The French raiding party that sacked and burned Southampton in 1338 brought with them a ribaudequin and 48 bolts (but only 3 pounds of gunpowder). The Battle of Crécy in 1346 was one of the first in Europe where cannons were used. In 1350, only four years later, Petrarch wrote that the presence of cannons on the battlefield was 'as common and familiar as other kinds of arms'.

References to gunnis cum telar (guns with handles) were recorded in 1350, and by 1411 it was recorded that John the Good, Duke of Burgundy, had 4000 handguns stored in his armory. However, musketeers and musket-wielding infantrymen were despised in society by the traditional feudal knights, even until the time of Cervantes (1547-1616 AD). At first even Christian authorities made vehement remarks against the use of gunpowder weapons, calling them blasphemous and part of the 'Black Arts'. By the mid 14th century, however, even the army of the Pope would be armed with artillery and gunpowder weapons.

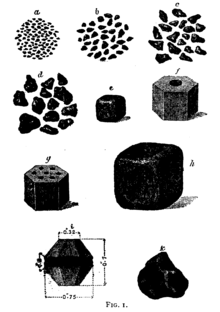

Around the late 14th century, European powdermakers began adding liquid to the constituents of gunpowder to reduce dust and with it the risk of explosion. The powdermakers would then shape the resulting paste of moistened gunpowder—known as mill cake—into "corns," or granules, to dry. Not only did "corned" powder keep better because of its reduced surface area, gunners also found that it was more powerful and easier to load into guns. The main advantage of corning is that the flame spreads between the granules, lighting them all, before significant gas expansion has occurred (when the gunpowder explodes). Without corning much of the powder away from the initial flame would be blown out of the barrel before it burnt. The size of the granules was different for different types of gun. Prior to corning, gunpowder would gradually demix into its constitutive components and was too unreliable for effective use in guns . The same granulation process is used nowadays in the pharmaceutical industry to ensure that each tablet contains the same proportion of active ingredient. Before long, powdermakers standardized the process by forcing mill cake through sieves instead of corning powder by hand.

The 15th through 17th century saw widespread development in gunpowder technology mainly in Europe. Advances in metallurgy led to portable weapons and the development of hand-held firearms such as muskets. Cannon technology in Europe gradually outpaced that of China and these technological improvements transferred back to China through Jesuit missionaries who were put in charge of cannon manufacture by the late Ming and early Qing emperors.

Shot and gunpowder for military purposes were made by skilled military tradesmen, who later were called firemakers, and who also were required to make fireworks for celebrations of victory or peace. During the Renaissance, two European schools of pyrotechnic thought emerged, one in Italy and the other at Nürnberg, Germany. The Italian school of pyrotechnics emphasized elaborate fireworks, and the German school stressed scientific advancement. Both schools added significantly to further development of pyrotechnics, and by the mid-17th century fireworks were used for entertainment on an unprecedented scale in Europe, being popular even at resorts and public gardens.

Mining

Until the invention of explosives, large rocks could only be broken up by hard labour, or heating with large fires followed by rapid quenching. Black powder was used in civil engineering and mining as early as the 15th century. The earliest surviving record for the use of gunpowder in mines comes from Hungary in 1627. It was introduced to Britain in 1638 by German miners, after which records are numerous. Until the invention of the safety fuse by William Bickford in 1831, the practice was extremely dangerous. Another reason for danger was the dense fumes given off and the risk of igniting flammable gas when used in coal mines.

Canals

The first time gunpowder was used on a large scale in civil engineering was in the construction of the Canal du Midi in Southern France. It was completed in 1681 and linked the Mediterranean sea with the Bay of Biscay with 240 km of canal and 100 locks. Another noteworthy consumer of blackpowder was the Erie canal in New York, which was 585 km long and took eight years to complete, starting in 1817.

Tunnel construction

Black powder was also extensively used in railway construction. At first railways followed the contours of the land, or crossed low ground by means of bridges and viaducts; but later railways made extensive use of cuttings and tunnels. One 800-metre stretch of the 3.3 km Box Tunnel on the Great Western Railway line between London and Bristol consumed a tonne of gunpowder per week for over two years. The 12.9 km long Mont Cenis Tunnel was completed in 13 years starting in 1857, but even with black powder progress was only 25 cm a day until the invention of pneumatic drills sped up the work.

The latter half of the 19th Century saw the invention of nitroglycerin, nitrocellulose and smokeless powders, which soon replaced black powder in many applications.

See also

- Black powder substitute

- Early thermal weapons

- Gonne

- Green mix

- Gunpowder warfare

- Huolongjing

- Jiao Yu

- Meal powder

- Technology of Song Dynasty

Notes

- "The Genius of China", Robert Temple

- Bhattacharya (in Buchanan 2006, p. 42) acknowledges that "most sources credit the Chinese with the discovery of gunpowder" though he himself disagrees.

- ^ Chase 2003:31–32

- Buchanan. "Editor's Introduction: Setting the Context", in Buchanan 2006.

- Kelly 2004:4

- Gernet, Jacques (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Trans. J. R. Foster & Charles Hartman (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. p. 311.

The discovery originated from the alchemical researches made in the Taoist circles of the T'ang age, but was soon put to military use in the years 904–6. It was a matter at that time of incendiary projectiles called 'flying fires' (fei-huo).

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Feng 1954:15-16 harvcolnb error: no target: CITEREFFeng1954 (help)

- Zhong 1995:60 harvcolnb error: no target: CITEREFZhong1995 (help)

- Needham 1986:220–262

- Lu, Needham & Phan 1988 harvcolnb error: no target: CITEREFLuNeedhamPhan1988 (help)

- Chase 2003:31–32

- Needham 1986:290

- Zhong 1995:193-194

- Wang 1991:50-58

- Kelly 2004:10

- Xu 1986:29 harvcolnb error: no target: CITEREFXu1986 (help)

- Feng 1991:461 harvcolnb error: no target: CITEREFFeng1991 (help)

- ^ Needham 1986:345

- Needham 1986:347

- Liu 2004:47–50 harvcolnb error: no target: CITEREFLiu2004 (help)

- ^ Needham 1986:126

- Crosby 2002:100–103

- Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 510.

- Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 192–199.

- ^ Needham 1986:209–210

- Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 173-174.

- Liu 2004:46-47

- Ebrey, 138.

- Wang 1991:48

- Kelly 2004:17

- Wang 1991: 103-115

- Kelly 2004:23–25

- ^ Urbanski 1967, Chapter III: Blackpowder Cite error: The named reference "urbanski" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Kelly 2004:22 'Around 1240 the Arabs acquired knowledge of saltpeter ("Chinese snow") from the East, perhaps through India. They knew of gunpowder soon afterward. They also learned about fireworks ("Chinese flowers") and rockets ("Chinese arrows"). Arab warriors had acquired fire lances before 1280. Around that same year, a Syrian named Hasan al-Rammah wrote a book that, as he put it, "treats of machines of fire to be used for amusement or for useful purposes." He talked of rockets, fireworks, fire lances, and other incendiaries, using terms that suggested he derived his knowledge from Chinese sources. He gave instructions for the purification of saltpeter and recipes for making different types of gunpowder.'

- C. F. Temler, Historische Abhandlungen der Koniglichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Kopenhagen . . . ubersetzt . . . von V. A. Heinze, Kiel, Dresden and Leipzig, 1782, i, 168, as cited in Partington, p.228, footnote 6

- Hassan, Ahmad Y. "Transfer of Islamic Technology to the West: Part III". History of Science and Technology in Islam.

- ^ al-Hassan harvcolnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFal-Hassan (help)

- Khan 1996

- ^ Khan 2004:6

- Johnson harvcoltxt error: no target: CITEREFJohnson (help)

- al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. "Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources". History of Science and Technology in Islam. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

The general notion that saltpetre was not known till the thirteenth century in Arabic alchemy and chemistry is reflected in other works on the history of chemistry.

- al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. "Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources". History of Science and Technology in Islam. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Ahmad Y Hassan (1987), "Chemical Technology in Arabic Military Treatises", Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, New York Academy of Sciences: 153-166

- Ahmad Y Hassan (1987), "Chemical Technology in Arabic Military Treatises", Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, New York Academy of Sciences: 153-166

- Arslan Terzioglu (2007), The First Attempts of Flight, Automatic Machines, Submarines and Rocket Technology in Turkish History, The Turks (ed. H. C. Guzel), pp. 804-10

- Ahmad Y Hassan (1987), "Chemical Technology in Arabic Military Treatises", Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, New York Academy of Sciences: 153-166

- Demonstrated in What the Ancients Did for Us, "Episode one: The Islamic World"

- Chase 2003:130

- ^ Khan 2004:9–10

- Partington (Johns Hopkins University Press edition, 1999), 217

- Khan 2004:10

- Partington, 226 (Johns Hopkins University Press edition, 1999)

- Partington (Johns Hopkins University Press edition, 1999), 225

- Partington (Johns Hopkins University Press edition, 1999), 226

- ^ "India." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica 2008 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008.

- "Chāpra." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica 2008 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008.

- A. K. Bag (2005), "Fathullah Shirazi: Cannon, Multi-barrel Gun and Yarghu", Indian Journal of History of Science 40 (3), pp. 431-436.

- "rocket and missile system." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica 2008 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008.

- Norris 2003:11

- ^ Chase 2003:58

- "The Eastern Origins of Western Civilization", John M.Hobson, p186, ISBN 0521547245

- Kelly 2004:25

- Kelly 2004:23

- ^ Kelly 2004:29

- Crosby 2002:120

- Kelly 2004:19–37

- Norris 2003:19

- Norris 2003:8

- ^ Norris 2003:12

- Molerus, Otto. "History of Civilization in the Western Hemisphere from the Point of View of Particulate Technology, Part 2," Advanced Powder Technology 7 (1996): 161-66

- Kelly 2004:60–63

- "Fireworks," Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007 © 1997-2007 Microsoft Corporation. All Rights Reserved.

- Earl 1978, Chapter 2: The Development of Gunpowder

- Earl, (1978). Chapter 1: Introduction

- ^ Brown (1998), Chapter 6: Mining and Civil Engineering

References

- Guns and Rifles of the World by Howard Blackmore ISBN 0-670-35780-4

- Brown, G. I. (1998), The Big Bang: A History of Explosives, Sutton Publishing, ISBN 0-7509-1878-0.

- Buchanan, Brenda J., ed. (2006), Gunpowder, Explosives and the State: A Technological History, Aldershot: Ashgate, ISBN 0754652599.

- Chase, Kenneth (2003), Firearms: A Global History to 1700, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521822742.

- Cocroft, Wayne (2000), Dangerous Energy: The archaeology of gunpowder and military explosives manufacture, Swindon: English Heritage, ISBN 1-85074-718-0.

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2002), Throwing Fire: Projectile Technology Through History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521791588.

- Davis, Tenney L. (1943). The Chemistry of Powder & Explosives. (Republished) ISBN 0-913022-00-4.

- Earl, Brian (1978), Cornish Explosives, Cornwall: The Trevithick Society, ISBN 0-904040-13-5.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43519-6 (hardback); ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback).

- Elliot, Henry M. (1875), The History of India as told by its own Historians. The Muhammadan Period. Volume VI. (Elibron Classics Replica Edition (2006) ed.), London: Trubner and Co., ISBN 0-543-94714-1

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help). - Feng Jiasheng (1954). The Invention of Gunpowder and Its Spread to The West. Shanghai: Shanghai People's Press. TQ56-09/1.

- Feng Wu, et al (1992). Selection of Ancient Chinese Military Masterpieces. Bejing: Jingguan Jiaoyu Press. ISBN 7-81027-097-4.

- From Greek fire to dynamite.A cultural history of the explosives by Jochen Gartz.E.S.Mittler &Sohn. Hamburg year 2007,ISBN 978-3-8132-0867-2.

- Gopal, Lallanji (1962), "The Śukranīti—A Nineteenth-Century Text", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 25 (1/3): 524–556.

- al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (2001), "Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources", History of Science and Technology in Islam, retrieved 2007-07-23.

- Kelly, Jack (2004), Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World, Basic Books, ISBN 0465037186.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (1996), "Coming of Gunpowder to the Islamic World and North India: Spotlight on the Role of the Mongols", Journal of Asian History, 30: 41–5.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2004), Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India, Oxford University Press

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, ISBN 981-05-5380-3

- Liu Xu (2004). History of Ancient Chinese Firearms and Black Powder. Zhengzhou: Elephant Press. ISBN 7-5347-3028-7.

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, vol. V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521303583.

- Norris, John (2003), Early Gunpowder Artillery: 1300-1600, Marlborough: The Crowood Press.

- Partington, J.R. (1960), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Cambridge, UK: W. Heffer & Sons.

- Partington, James Riddick (1999). A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5954-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Urbanski, Tadeusz (1967), Chemistry and Technology of Explosives, vol. III, New York: Pergamon Press.

- Wang Zhaocun (1991). A History of Chinese Firearms. Beijing: Military Science Press. ISBN 7-80021-304-8.

- Xu Huilin (1986). A History of Chinese Black Powder and Firearms. Shanghai: Kexuepuji Press. CN / TQ56-092.

- Zhang, Yunming (1986), "Ancient Chinese Sulfur Manufacturing Processes", Isis, 77 (3): 487–497.

- Zhong Shaoyi (1995). Research on the History of Ancient Chinese Black Powder and Firearms. Beijing: Chinese Social Sciences Press. ISBN 7-5004-1800-0

- Johnson, Norman Gardner (2008), "History of black powder" in "explosive", Encyclopædia Britannica.