This is an old revision of this page, as edited by ClueBot (talk | contribs) at 07:25, 3 August 2009 (Reverting possible vandalism by 220.244.58.10 to version by ArthurBot. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot. (748505) (Bot)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 07:25, 3 August 2009 by ClueBot (talk | contribs) (Reverting possible vandalism by 220.244.58.10 to version by ArthurBot. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot. (748505) (Bot))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) "King Tut" redirects here. For other uses, see King Tut (disambiguation).| Tutankhamun | |

|---|---|

| Tutankhamen, Tutankhaten, Tutankhamon possibly Nibhurrereya (as referenced in the Amarna letters) | |

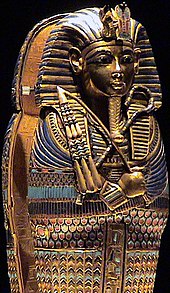

Mask of Tutankhamun's mummy, the popular icon for ancient Egypt at The Egyptian Museum. Mask of Tutankhamun's mummy, the popular icon for ancient Egypt at The Egyptian Museum. | |

| Pharaoh | |

| Reign | 1333–1324 BCE |

| Predecessor | Smenkhkare? or Neferneferuaten? |

| Successor | Ay |

| Royal titulary

| |

| Consort | Ankhesenamen |

| Children | 2 possibly, both female, names unknown |

| Father | Akhenaten? |

| Mother | Kiya? she was a widow Nefertiti(stepmother) |

| Born | 1341 BC |

| Died | 1323 BC |

| Burial | KV62 |

| Dynasty | 18th Dynasty |

Tutankhamun (alternately spelled with Tutenkh-, -amen, -amon), Egyptian twt-ˁnḫ-ı͗mn; tVwa:t-ʕa:nəx-ʔaˡma:n (1341 BC – 1323 BC) was an Egyptian Pharaoh of the Eighteenth dynasty (ruled 1333 BC – 1324 BC in the conventional chronology), during the period of Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom. His original name, Tutankhaten, means "Living Image of Aten", while Tutankhamun means "Living Image of Amun". Often the name Tutankhamun was written Amen-tut-ankh, meaning "living image of Amun", due to scribal custom which most often placed the divine name at the beginning of the phrase in order to honor the divine being. He is possibly also the Nibhurrereya of the Amarna letters. He was likely the eighteenth dynasty king 'Rathotis', who according to Manetho, an ancient historian, had reigned for nine years — a figure which conforms with Flavius Josephus' version of Manetho's Epitome.

The 1922 discovery by Howard Carter of Tutankhamun's intact tomb received worldwide press coverage and sparked a renewed public interest in ancient Egypt, for which Tutankhamun's burial mask remains the popular face.

Life

Significance

Tutankhamun was nine years old when he became pharaoh and reigned for approximately ten years. In historical terms, Tutankhamun's significance stems from his rejection of the radical religious innovations introduced by his predecessor Akhenaten and that his tomb in the Valley of the Kings was discovered by Carter almost completely intact — the most complete Ancient Egyptian royal tomb ever found. As Tutankhamun began his reign at such an early age, his vizier and eventual successor Ay was probably making most of the important political decisions during Tutankhamun's reign.

Tutankhamun was one of the few kings worshiped as a god and honored with a cult-like following in his own lifetime. A stela discovered at Karnak and dedicated to Amun-Re and Tutankhamun indicates that the king could be appealed to in his deified state for forgiveness and to free the petitioner from an ailment caused by wrongdoing. Temples of his cult were also built as far as Kawa and Faras in Nubia. The title of the sister of the Viceroy of Kush included a reference to the deified king indicative of the universality of his cult.

Parentage

Tutankhamun's parentage is uncertain. An inscription calls him a king's son, but it is not clear which king was meant.

He was originally thought to be a son of Amenhotep III and his Great Royal Wife Queen Tiye. Later research claimed that he may have been a son of Amenhotep III, although not by Queen Tiye, since Tiye would have been more than fifty years old at the time of Tutankhamun's birth.

At present, the most common hypothesis holds that Tutankhamun was the son of Akhenaten, also known as Amenhotep IV, and his minor wife Queen Kiya. Queen Kiya's title was "Greatly Beloved Wife of Akhenaten" so it is possible that she could have borne him an heir. Supporting this theory, images on the tomb wall in the tomb of Akhenaten show a royal fan bearer standing next to Kiya's death bed, fanning someone who is either a princess or more likely, a wet nurse holding a baby, considered to be the wet nurse and the boy, king-to-be. Recently however Zahi Hawass has definitely confirmed that Tutankhamen is the biological son of Akhenaten due to the recovery of a part of a limestone block that identifies both he and his wife Ankhesenpaaten as children of the king's body. Since Ankhesenpaaten is known to be Akhenaten's daughter, Hawass concludes that Tutankhamun must be also. Whether his mother is indeed Nefertiti or Kiya is still to be determined.

Professor James Allen argues that Tutankhamun was more likely to be a son of the short-lived king Smenkhkare rather than Akhenaten. Allen argues that Akhenaten consciously chose a female co-regent named Neferneferuaten as his successor, rather than Tutankhamun, which would have been unlikely if the latter had been his son. Smenkhkare appears when Akhenaten entered year 14 of his reign and it is thought that during this time Meritaten married Smenkhkare. Smenkhkare, as the father of Tutankhamun, needed at least a three year reign to bring Tutankhamun to the right age to have inherited the throne. However, if there had been lengthy co-regency between Amenhotep III and Akhenaten, Amenhotep definitely could be Tutankhamun's father.

Reign

Given his age, the king must have had very influential advisors, presumably including General Horemheb, the Vizier Ay and Maya the "Overseer of the Treasury". Horemheb records that the King appointed him Lord of the land as Hereditary Prince to maintain law and how he could also calm the young King when his temper flared in the palace.

In his third regnal year the King changed his name from Tutankhaten to Tutankhamun. Akhenaten's Amarna revolution (Atenism) was now reversed. Akhenaten had attempted to supplant the traditional priesthood and deities with a god, Aten, who was until then considered minor. The ban on the old pantheon of deities and their temples was lifted. The traditional privileges were restored to their priesthoods, and the capital was moved back to Thebes with the city of Akhenaten abandoned.

The "Restoration Stela" erected in the temple at Karnak describes the pharaoh's perception of the changes brought about by Ahkenaten and the reasons for his reversals:

The temples of the gods and goddesses ... were in ruins. Their shrines were deserted and overgrown. Their sanctuaries were as non-existent and their courts were used as roads ... the gods turned their backs upon this land ... If anyone made a prayer to a god for advice he would never respond – and the same applied to a goddess.

As part of his restoration process the king initiated building projects, in particular at Thebes and Karnak where he dedicated a temple to Amun. Many monuments were also erected, an inscription on his tomb door declaring that the king had "spent his life in fashioning the images of the gods". The traditional festivals were now celebrated again including those related to the Apis Bull, Horemakhet and Opet. His Restoration Stela declares

Now the gods and goddesses of the land are rejoicing in their hearts...the provinces all rejoice and celebrate throughout this whole land because good has come back into existence.

The country was economically weak and in turmoil following the reign of Akhenaten. Diplomatic relations with other kingdoms had been neglected and Tutankhamun sought to restore them, in particular with the Mittani, and evidence of his success is witnessed by the gifts from various countries found in his tomb. Despite his efforts for improved relations battles with Nubians and Asiatics were recorded in his mortuary temple at Thebes. His tomb contained body armour and campaign folding stools but in view of his age there is speculation that he did not take part personally in these battles.

On becoming king he married Ankhesenepatan who changed her name to Ankhesenamun when he changed his to Tutankhamun. They had no surviving offspring but two female babies were found in small coffins in the kings tomb, neither of whom had reached full gestation. The only name found on their coffins was "Osiris", a reference to rebirth in the next life.

Burial

Tutankhamun was buried in small tomb relative to his status. His death may have occurred unexpectedly, before the completion of a grander royal tomb, so that his mummy was buried in a tomb intended for someone else, perhaps Ay. This would preserve the observance of the customary seventy days between death and burial.

Name

| Horus name |

|

Kanakht Tutmesut The strong bull, pleasing of birth | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nebti name |

|

Neferhepusegerehtawy Wer-Ah-Amun Neb-r-Djer One of perfect laws, who pacifies the two lands; Great of the palace of Amun; Lord of all | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Golden Horus name |

|

Wetjeskhausehetepnetjeru Heqa-maat-sehetep-netjeru Wetjes-khau-itef-Re Wetjes-khau-Tjestawy-Im Who wears crowns and pleases the gods; Ruler of Truth, who pleases the gods; Who wears the crowns of his father, Re; Who wears crowns, and binds the two lands therein | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prenomen |

|

Nebkheperure Lord of the forms of Re | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Son of Re |

|

Tutankhamun Hekaiunushema Living Image of Amun, ruler of Upper Heliopolis |

He is depicted only once as a prince, on a block from Hermopolis, where he is called Tutankwhaten (twt-ˁnḫw-ỉtn), but when his reign started, he was known as Tutankhaten (twt-ˁnḫ-ỉtn), which in Egyptian hieroglyphs is:

| |

At the reintroduction of traditional religious practise, his name changed. It is transliterated as twt-ˁnḫ-ỉmn ḥq3-ỉwnw-šmˁ, and often realized as Tutankhamun Hekaiunushema, meaning "Living image of Amun, ruler of Upper Heliopolis". On his ascension to the throne, Tutankhamun took a praenomen. This is translated as nb-ḫprw-rˁ, and realized as Nebkheperure, meaning "Lord of the forms of Re". The name Nibhurrereya in the Amarna letters may be a variation of this praenomen.

Cause of death

The cause of Tutankhamun's death is unclear, and is still the root of much speculation. In early 2005 the results of a set of CT scans on the mummy were released.

The body originally was looked at by Howard Carter's team in the early 1920s, although they were primarily interested in recovering the jewelry and amulets from the body. To remove these objects from the body, which often were stuck fast by the hardened embalming resins used, Carter's team cut up the mummy into various pieces: the arms and legs were detached, the torso cut in half and the head was severed. Hot knives were used to remove it from the golden mask to which it was cemented by resin.

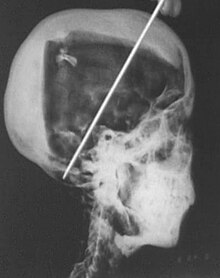

Since 1926, the mummy has been X-rayed three times: first in 1968 by a group from the University of Liverpool led by Dr. R. G. Harrison, then in 1978 by a group from the University of Michigan, and finally in 2005 a team of Egyptian scientists led by Secretary General of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, Dr. Zahi Hawass, who conducted a CT scan on the mummy.

X-rays of Tutankhamun's mummy, taken in 1968, revealed a dense spot at the lower back of the skull interpreted as a subdural hematoma. Such an injury could have been the result of an accident, but it also had been suggested that the young pharaoh was murdered. A trauma specialist from Long Island University at C. W. Post Campus insisted that this injury could not have been from a natural cause. The specialist stated that the blow was to a protected area at the back of the head which is not easily injured in an accident. Theories as to who was responsible for the death include Tutankhamun's immediate successor Ay, his wife, and his chariot-driver. Calcification within the supposed injury indicates Tutankhamun lived for a fairly extensive period of time (on the order of several months) after the injury was inflicted.

A small, loose, sliver of bone was discovered within the upper cranial cavity, which was discovered from the same X-ray analysis. In fact, since Tutankhamun's brain was removed post mortem in the mummification process, and considerable quantities of now-hardened resin introduced into the skull on at least two separate occasions after that, had the fragment resulted from a pre-mortem injury, some scholars, including the 2005 CT scan team, say it almost certainly would not still be loose in the cranial cavity. But other scientists suggested, that the loose sliver of bone was loosened by the embalmers during mummification, but it had been broken before. A blow to the back of the head (from a fall or an actual blow), caused the brain to move forward, hitting the front of the skull, breaking small pieces of the bone right above the eyes.

2005 findings

On March 8, 2005, Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass revealed the results of a CT scan performed on the pharaoh's mummy. The scan uncovered no evidence of a blow to the back of the head and no evidence suggesting foul play. There was a crack in the skull, but it appeared to have been drilled, by embalmers. A fracture to Tutankhamun's left thighbone was interpreted as evidence that the pharaoh badly broke his leg shortly before he died and his leg became severely infected; however, members of the Egyptian-led research team recognized, as a less likely possibility, that the fracture was caused by the embalmers. All together, 1,700 images were produced of Tutankhamun's mummy during the 15-minute CT scan.

Much was learned about the young king's life. His age at death was estimated at nineteen years, based on physical developments that set upper and lower limits to his age (though expert orthodontists have now studied his teeth and have estimated the King died in his early twenties). The king had been in general good health and there were no signs of any major infectious disease or malnutrition during his childhood. He was slight of build, and was roughly 170 cm (5 ft 7 in) tall. He had large front incisors and the overbite characteristic of the Thutmosid royal line to which he belonged. He also had a pronounced dolichocephalic (elongated) skull, although it was within normal bounds and highly unlikely to have been pathological. Given the fact that many of the royal depictions of Akhenaten (possibly his father, certainly a relative), often featured such an elongated head, it is likely an exaggeration of a family trait, rather than a distinct abnormality. The research also showed that the pharaoh had "a slightly cleft palate". A slight bend to his spine also was found, but the scientists agreed that there was no associated evidence to suggest that it was pathological in nature, and that it was much more likely to have been caused by the embalming process. This ended speculation based on the previous X-rays that Tutankhamun had suffered from scoliosis. However, it was subsequently noted by Zahi Hawass that the mummy found in KV55, provisionally identified as Tutankhamun's father, exhibited several similarities to that of Tutankhamun — a cleft palate, a dolichocephalic skull and slight scoliosis (also found on one of her stillborns), the first and third elements being a common defect on people suffering from Klippel-Feil syndrome or Marfans syndrome, which incapacitated him and might have played a role in his accidental death. The large number of walking sticks found in the prince's tomb also suggests some medical problem.

The 2005 conclusion by a team of Egyptian scientists, based on the CT scan findings, is that Tutankhamun died of gangrene after breaking his leg. After consultations with Italian and Swiss experts, the Egyptian scientists found that the fracture in Tutankhamun's left leg most likely occurred only days before his death, which had then become gangrenous and led directly to his death. The fracture in their opinion was not sustained during the mummification process or as a result of some damage to the mummy as claimed by Howard Carter. The Egyptian scientists also have found no evidence that he had been struck on the head and no other indication that he was murdered, as had been speculated previously. Further investigation of the fracture led to the conclusion that it was severe, most likely caused by a fall from some height — possibly a chariot riding accident due to the absence of pelvis injuries — and may have been fatal within hours

Despite the relatively poor condition of the mummy, the Egyptian team found evidence that great care had been given to the body of Tutankhamun during the embalming process. They found five distinct embalming materials, which were applied to the body at various stages of the mummification process. This counters previous assertions that the king’s body had been prepared carelessly and in a hurry. In November 2006, at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, Egyptian radiologists stated that CT images and scans of the king's mummy revealed Tutankhamun's height to be 5 feet 6 inches tall, a revision upward from the earlier estimates.

Michael R. King continues to dispute these findings, claiming that the king was murdered. He argues that the loose sliver of bone was loosened by the embalmers during mummification, but that it had been broken before. He argues that a blow to the back of the head (from a fall or an actual blow) may have caused the brain to move forward, hitting the front of the skull, breaking small pieces of the bone right above the eyes. Tut could have died of a Contra-coup injury, in which he hit the front of his head, resulting in hemorrhaging. This would make it look like he was blugeoned, but what most likely happened is that he fell off his chariot. The evidence that he died away from 'home' is that he had an excess of resin poured on him (more than usual), to hide the smell of decay. He also had flowers that only bloom in the spring wrapped around his neck. Since mummification takes a process of about 3 to 4 months, he would have died in December or January, which is during the hunting season.

Discovery of tomb

Main article: KV62

Tutankhamun seems to have faded from public consciousness in Ancient Egypt within a short time after his death, and he remained virtually unknown until the early twentieth century. His tomb was robbed at least twice in antiquity, but based on the items taken (including perishable oils and perfumes) and the evidence of restoration of the tomb after the intrusions, it seems clear that these robberies took place within several months at most of the initial burial. Eventually the location of the tomb was lost because it had come to be buried by stone chips from subsequent tombs, either dumped there or washed there by floods. In the years that followed, some huts for workers were built over the tomb entrance, clearly not knowing what lay beneath. When at the end of the twentieth dynasty the Valley of the Kings burials were systematically dismantled, the burial of Tutankhamun was overlooked, presumably because knowledge of it had been lost and his name may have been forgotten.

For many years, rumors of a "Curse of the Pharaohs" (probably fueled by newspapers seeking sales at the time of the discovery) persisted, emphasizing the early death of some of those who had first entered the tomb. However, a recent study of journals and death records indicates no statistical difference between the age of death of those who entered the tomb and those on the expedition who did not. Indeed, most lived past seventy.

KV is an abbreviation for the Valley of the Kings, followed by a number to designate individual tombs in the Valley. Ancient Egyptian senet games similar to the one displayed at the right, were found in the tomb.

Some of the treasures in Tutankhamun's tomb are noted for their apparent departure from traditional depictions of the boy king. Certain cartouches where a king's name should appear have been altered, as if to reuse the property of a previous pharaoh—as often occurred. However, this instance may simply be the product of "updating" the artifacts to reflect the shift from Tutankhaten to Tutankhamun. Other differences are less easy to explain, such as the older, more angular facial features of the middle coffin and canopic coffinettes. The most widely accepted theory for these latter variations is that the items were originally intended for Smenkhkare, who may or may not be the mysterious KV55 mummy. Said mummy, according to craniological examinations, bears a striking first-order (father-to-son, brother-to-brother) relationship to Tutankhamun.

2007 discoveries

On September 24, 2007, it was announced that a team of Egyptian archaeologists, led by Zahi Hawass, discovered eight baskets of 3,000 year old doum fruit in the treasury of Tutankhamun's tomb. Doum comes from a type of palm tree native to the Nile Valley. The doum fruit are traditionally offered at funerals.

Fifty clay pots bearing Tutankhamun's official seal were also discovered. According to Dr Hawas, the containers probably contained money that were destined to travel with the pharaoh to the afterlife. He said the containers will soon be opened. The objects were originally discovered, but not opened or removed from the tomb, by Howard Carter.

King Tutankhamun still rests in his tomb in the Valley of the Kings, in a temperature-controlled glass case. On November 4, 2007, 85 years to the day since Howard Carter's discovery, the actual face of the 19-year-old pharaoh was put on view in his underground tomb at Luxor, when the linen-wrapped mummy was removed from its golden sarcophagus for display in a climate-controlled glass box. This was done to prevent the heightened rate of decomposition caused by the humidity and warmth from tourists visiting the tomb.

Appearance

| This article's factual accuracy is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help to ensure that disputed statements are reliably sourced. (July 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In 2005, three teams of scientists (Egyptian, French, and American), in partnership with the National Geographic Society, developed a new facial likeness of Tutankhamun. The Egyptian team worked from 1,700 three-dimensional CT scans of the pharaoh's skull. The French and American teams worked plastic moulds created from these—but the Americans were never told who the subject of the reconstruction was. All three teams created silicone busts of their interpretation of what the young monarch looked like.

Skin tone

Although modern technology can reconstruct Tutankhamun's facial structure with a high degree of accuracy based on CT data from his mummy, correctly determining his skin tone is impossible. There is no consensus on Tutankhamun's skin tone.

Terry Garcia, National Geographic's executive vice president for mission programs, said, in response to some protesters of the Tutankhamun reconstruction:

The big variable is skin tone. North Africans, we know today, had a range of skin tones, from light to dark. In this case, we selected a medium skin tone, and we say, quite up front, 'This is midrange.' We will never know for sure what his exact skin tone was or the color of his eyes with 100% certainty. ... Maybe in the future, people will come to a different conclusion.

Zahi Hawass, the head of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities, however, rejects the claims of Afrocentrists that Tutankhamun himself was black. According to Dr. Hawass: "Tutankhamun was not black, and the portrayal of ancient Egyptian civilization as black has no element of truth to it;" Hawass further observed that " Egyptians are not Arabs and are not Africans despite the fact that Egypt is in Africa."

Exhibitions

The splendors of Tutankhamun's tomb are among the most traveled artifacts in the world. They have been to many countries, but probably the best-known exhibition tour was the Treasures of Tutankhamun tour, which ran from 1972-1979. This exhibition was first shown in London at the British Museum from March 30 until September 30, 1972. More than 1.6 million visitors came to see the exhibition, some queueing for up to eight hours and it was the most popular exhibition ever in the Museum. The exhibition moved on to many other countries, including the USA, USSR, Japan, France, Canada, and West Germany. The exhibition in the United States was organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and ran from November 17, 1976 through April 15, 1979. It was attended by more than eight million people in the United States.

An excerpt from the site of the American National Gallery of Art:

...55 objects from the tomb of Tutankhamun included the boy-king's solid gold funeral mask, a gilded wood figure of the goddess Selket, lamps, jars, jewelry, furniture, and other objects for the afterlife. This exhibition established the term 'blockbuster.' A combination of the age-old fascination with ancient Egypt, the legendary allure of gold and precious stones, and the funeral trappings of the boy-king created an immense popular response. Visitors waited up to 8 hours before the building opened to view the exhibition. At times the line completely encircled the West Building.

In 2004, the tour of Tutenkhamen funerary objects entitled "Tutenkhamen: The Golden Hereafter" made up of fifty artifacts from Tutenkhamun’s tomb and seventy funerary goods from other 18th Dynasty tombs began in Basle, Switzerland, went to Bonn Germany, the second leg of the tour, and from there toured the United States . The exhibition returned to Europe and to London. The European tour was organised by the Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany, the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), and the Egyptian Museum in cooperation with the Antikenmuseum Basel and Sammlung Ludwig. Deutsche Telekom sponsored the Bonn exhibition.

In 2005, Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities, in partnership with Arts and Exhibitions International and the National Geographic Society, launched the U.S. tour of the Tutenkahamun treasures and other 18th Dynasty funerary objects this time called "Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs." It was expected to draw more than three million people.

The exhibition started in Los Angeles, California, then moved to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, Chicago and Philadelphia. The exhibition then moved to London before finally returning to Egypt in August 2008. Subsequent events have propelled an encore of the exhibition in the United States, beginning with the Dallas Museum of Art in October 2008 which will host the exhibition until May 2009. The tour will continue to two other U.S. cities, the second of which has yet to be named, but after Dallas the exhibition will continue to the de Young Museum in San Francisco and the Discovery Times Square Exposition in New York City.

The exhibition includes 80 exhibits from the reigns of Tutankhamun's immediate predecessors in the eighteenth dynasty, such as Hatshepsut, whose trade policies greatly increased the wealth of that dynasty and enabled the lavish wealth of Tutankhamun's burial artifacts, as well as 50 from Tutankhamun's tomb. The exhibition does not include the gold mask that was a feature of the 1972-1979 tour, as the Egyptian government has determined that the mask is too fragile to withstand travel and will never again leave the country.

A separate exhibition called "Tutankhamun and the World of the Pharaohs" began at the Ethnological Museum in Vienna from March 9 to September 28, 2008 showing a further 140 treasures from the tomb. This exhibition continued to Atlanta and will continue to Indianapolis at the Indianapolis Children's Museum.

In popular culture

Main article: Egypt in the European imaginationIf Tutankhamun is the world's best known pharaoh, it is partly because his tomb is among the best preserved, and his image and associated artifacts the most-exhibited. He also has entered popular culture—he has, for example, been commemorated in the whimsical 1978 song "King Tut" by the American comedian Steve Martin with a backup group he called "The Toot Uncommons". He was also the namesake of one of Batman's arch enemies played by Victor Buono in the 1960s American television series "Batman" with Adam West.

In 1939, slapstick comedy trio the Three Stooges filmed We Want Our Mummy, in which they explored the tomb of the midget King Rutentuten (pronounced "rootin'-tootin'") and his Queen, Hotsy Totsy. A decade later, they were crooked used-chariot salesmen in Mummy's Dummies, in which they ultimately assist a different King Rootentootin (Vernon Dent) with a toothache.

As a side effect, the interest in this tomb and its alleged "curse" led to horror movies featuring a vengeful mummy. As Jon Manchip White writes, in his foreword to the 1977 edition of Carter's The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun, "The pharaoh who in life was one of the least esteemed of Egypt's kings has become in death the most renowned."

In fiction

King Tut, as played by Victor Buono, was a villain on the Batman TV series which aired from 1966 to 1968. Mild-mannered Egyptologist William Omaha McElroy, after suffering a concussion, came to believe he was the reincarnation of Tutankhamun. His response to this knowledge was to embark upon a crime spree that required him to fight against the "Caped Crusaders", Batman and Robin.

The Discovery Kids animated series Tutenstein stars a fictional mummy based on Tutankhamun, named Tutankhensetamun and nicknamed Tutenstein in his afterlife. He is depicted as a lazy and spoiled 10-year-old mummy boy who must guard a magical artifact called the Scepter of Was from the evil Egyptian god of Set.

The mummy of Tutankhamun is depicted as a villain in Raj Comics's Nagraj, a Hindi superhero comicbook. In this series, his mask is the source of his power.

The video game Sphinx and the Cursed Mummy features a fictional representation of Prince Tutankhamen. Tutankhamen is the victim of an unnamed magical ritual which results in almost instantaneous mummification and extraction of what appears to be his "life force". In the instruction manual, the Mummy is described as young, inexperienced and naive.

Gallery depicting kin

-

A wooden statue head of Queen Tiye, thought to be Tutankhamun's Grandmother, part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection

A wooden statue head of Queen Tiye, thought to be Tutankhamun's Grandmother, part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection

-

Fragmentary statue of Akhenaten, perhaps Tutankhamun's father, on display at the Cairo Museum

-

Plaster face of a young Amarna-era woman, thought to represent Queen Kiya, the likely mother of Tutankhamun, on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Plaster face of a young Amarna-era woman, thought to represent Queen Kiya, the likely mother of Tutankhamun, on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

-

Canopic jar depicting an Amarna-era Queen, usually identified as being Queen Kiya, on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Canopic jar depicting an Amarna-era Queen, usually identified as being Queen Kiya, on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

-

The iconic image of Queen Nefertiti, perhaps the step-mother of Tutankhamun, part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection

The iconic image of Queen Nefertiti, perhaps the step-mother of Tutankhamun, part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection

-

Another statue head depicting Nefertiti, now part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection

Another statue head depicting Nefertiti, now part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection

-

Fragmentary statue thought to represent Ankhesenamun, sister and wife to Tutankhamun, on display at the Brooklyn Museum

Fragmentary statue thought to represent Ankhesenamun, sister and wife to Tutankhamun, on display at the Brooklyn Museum

-

Statue of an unnamed Amarna-era princess, likely a sister (or step-sister) to Tutankhamun, part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection

Statue of an unnamed Amarna-era princess, likely a sister (or step-sister) to Tutankhamun, part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection

References

- Clayton, Peter A. (2006). Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p. 128. ISBN 0-500-28628-0.

- Zauzich, Karl-Theodor (1992). Hieroglyphs Without Mystery. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 30–31.

- "Manetho's King List".

- Aude Gros de Beler, "Tutankhamun", foreword Aly Maher Sayed, Moliere, ISBN 2-84790-210-4

- "Oxford Guide: Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology", Editor Donald B. Redford, p. 85, Berkley, ISBN 0-425-19096-x

- "The Boy Behind the Mask", Charlotte Booth, p. 120, Oneworld, 2007, ISBN 978-1-85168-544-8

- "retrieved 15 July 2009". Allaboutegypt.org. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

-

Allen, James P. (2006). "The Amarna Succession". Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane (Online publication in PDF). Memphis, TN: University of Memphis. pp. 7, 12–14. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.egyptology.com/kmt/fall97/endpaper.html A New Take on Tut's Parents by Dennis Forbes KMT 8:3 Fall 1997

- Booth p. 86-87

- "Akhenaten and the Religion of Light", Erik Hornung, Translated by David Lorton, Cornell University Press, 2001, ISBN 0801487250

- Hart, George (1990). Egyptian Myths. University of Texas Press. p. 47. ISBN 0292720769.

- Booth p. 107

- Booth p. 129-130

- Booth p. 76-79

- "The Golden Age of Tutankhamun: Divine Might and Splendour in the New Kingdom", Zahi Hawass, p. 61, American University in Cairo Press, 2004, ISBN 9774248368

- "Digital Egypt for Universities: Tutankhamun". University College London. June 22, 2003. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Jacobus van Dijk. "The Death of Meketaten" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-10-02.

{{cite web}}: Text "p.7" ignored (help) - "King Tut Murder Mystery Solved by LIU Egyptologist Bob Brier". Long Island University. 1997-01-17.

- ^ King, Michael R. (2006-09-13). Who Killed King Tut?: Using Modern Forensics to Solve a 3300-Year-Old Mystery (With New Data on the Egyptian CT Scan).

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|publication=ignored (help) - ^ Brier, Bob (1999). The Murder of Tutankhamun: A True Story.

- Handwerk, Brian (March 8, 2005). "King Tut Not Murdered Violently, CT Scans Show". National Geographic News. p. 2. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- Nefertiti and the Lost Dynasty, National Geographic Channel 2007

- The Assassination of Tutankhamun, Discovery Channel, 2006

- "h2g2 - Marfan Syndrome". BBC. 1978-01-02. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- Ian Sample (2006-10-28). "Boy king may have died in riding accident". The Guardian.

- "Radiologists attempt to solve mystery of Tut's demise". 2006-10-26.

- (Coplen, J. D. (n.d.). The Death of King Tutankhamun. Retrieved March 20, 2009, from The Tut Investigation: http://www.iois.net/TutInvestigation.htm).

- (King Tut 'died from broken leg' . (2005, March 8). Retrieved March 21, 2009, from BBC News: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/4328903.stm>

- "Welcome to Senet". Texas Humanities Resource Center. December 17, 2004. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- Reeves, Nicholas C. (1990-10-01). The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. Thames & Hudson.

- Michael McCarthy (2007-10-05). "3,000 years old: the face of Tutankhamun". The Independent.

- Handwerk, Brian (May 11, 2005). "King Tut's New Face: Behind the Forensic Reconstruction". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- "discovery reconstruction".

- "Science museum images". Sciencemuseum.org.uk. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- Henerson, Evan (June 15, 2005). "King Tut's skin colour a topic of controversy". U-Daily News — L.A. Life. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- "Egyptology News» Blog Archive » Hawass says that Tutankhamun was not black". Touregypt.net. 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- "NGA — Treasures of Tutankhamun (11/1976)". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- "Al-Ahram Weekly | Heritage | Under Tut's spell". Weekly.ahram.org.eg. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- "King Tut exhibition. Tutankhamun & the Golden Age of the Pharaohs. Treasures from the Valley of the Kings". Arts and Exhibitions International. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- Return of the King (Times Online)

- "Dallas Museum of Art Website". Dallasmuseumofart.org. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- Associated Press, "Tut Exhibit to Return to US Next Year"

- "Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs | King Tut Returns to San Francisco, June 27, 2009–March 28, 2010". Famsf.org. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- Jenny Booth (2005-01-06). "CT scan may solve Tutankhamun death riddle". The Times.

- Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

Further reading

- Andritsos, John. Social Studies of ancient Egypt: Tutankhamun. Australia 2006

- Booth, Charlotte. The Boy Behind the Mask", Oneworld, ISBN 978-1-85168-544-8

- Brier, Bob. The Murder of Tutankhamun: A True Story. Putnam Adult, April 13, 1998, ISBN 0425166899 (paperback)/ISBN 0-399-14383-1 (hardcover)/ISBN 0-613-28967-6 (School & Library Binding)

- Carter, Howard and Arthur C. Mace, The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun. Courier Dover Publications, June 1, 1977, ISBN 0-486-23500-9 The semi-popular account of the discovery and opening of the tomb written by the archaeologist responsible

- Desroches-Noblecourt, Christiane. Sarwat Okasha (Preface), Tutankhamun: Life and Death of a Pharaoh. New York: New York Graphic Society, 1963, ISBN 0-8212-0151-4 (1976 reprint, hardcover) /ISBN 0-14-011665-6 (1990 reprint, paperback)

- Edwards, I.E.S., Treasures of Tutankhamun. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1976, ISBN 0-345-27349-4 (paperback)/ISBN 0-670-72723-7 (hardcover)

- Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, The Mummy of Tutankhamun: the CT Scan Report, as printed in Ancient Egypt, June/July 2005.

- Haag, Michael. "The Rough Guide to Tutankhamun: The King: The Treasure: The Dynasty". London 2005. ISBN 1-84353-554-8.

- Hoving, Thomas. The search for Tutankhamun: The untold story of adventure and intrigue surrounding the greatest modern archeological find. New York: Simon & Schuster, October 15, 1978, ISBN 0-671-24305-5 (hardcover)/ISBN 0-8154-1186-3 (paperback) This book details a number of interesting anecdotes about the discovery and excavation of the tomb

- James, T. G. H. Tutankhamun. New York: Friedman/Fairfax, September 1, 2000, ISBN 1-58663-032-6 (hardcover) A large-format volume by the former Keeper of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum, filled with colour illustrations of the funerary furnishings of Tutankhamun, and related objects

- Reeeves, C. Nicholas. The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. London: Thames & Hudson, November 1, 1990, ISBN 0-500-05058-9 (hardcover)/ISBN 0-500-27810-5 (paperback) Fully covers the complete contents of his tomb

- Rossi, Renzo. Tutankhamun. Cincinnati (Ohio) 2007 ISBN 978-0-7153-2763-0, a work all illustrated and coloured.

External links

- Grim secrets of Pharaoh's city BBC News

- Tutankhamun and the Age of the Golden Pharaohs website

- The mummy's curse: historical cohort study Mark Nelson, British Medical Journal 2002;325:1482

- End Paper: A New Take on Tut's Parents by Dennis Forbes (KMT 8:3 . FALL 1997, KMT Communications)

- Original photographs and descriptions of objects found in the tomb by Carter and his team at the Griffith Institute, Oxford University

- The Independent, October 20, 2007: "A 3,000-year-old mystery is finally solved: Tutankhamun died in a hunting accident". See also video at The-Maker.net

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: