This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Pedro thy master (talk | contribs) at 19:26, 22 February 2010 (→1979-1984). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:26, 22 February 2010 by Pedro thy master (talk | contribs) (→1979-1984)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Shigeru Miyamoto | |

|---|---|

Shigeru Miyamoto Shigeru Miyamoto | |

| Born | (1952-11-16) November 16, 1952 (age 72) Sonobe cho, Kyoto, Japan |

| Occupation(s) | Game designer, EAD General manager |

| Years active | 1977-Present |

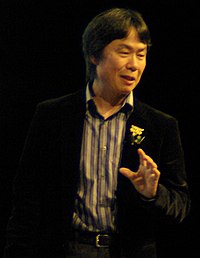

Shigeru Miyamoto (宮本 茂, Miyamoto Shigeru) (born November 16, 1952 in Sonobe, Kyoto, Japan) is a Japanese video game designer and producer who has been employed at Nintendo since 1977. He has been called the "father of modern video games" and "the Walt Disney of electronic gaming" for helping create the Mario, Donkey Kong, The Legend of Zelda, Star Fox, Pikmin and F-Zero franchises and games such as Nintendogs and Wii Music.

Early life

Miyamoto described childhood experiences such as exploring fields, woods and caves outside Kyoto as an inspiration for The Legend of Zelda for NES, and an antagonizing experience with a neighbor's chained dog, which inspired the Chain Chomp in the Mario series.

Career

1979-1984

Miyamoto was Nintendo's first artist staff, helping design the company's first coin-operated game, Sheriff. He also devoloped Radar Scope in Template:Vgy. As of the beginning of Template:Vgy, Nintendo's efforts to sell in the North American video game market had failed, culminating with the flop Radar Scope. To keep the company afloat, the then company president Hiroshi Yamauchi decided to convert unsold Radar Scope games into something new. He approached Miyamoto to see if he could design an arcade game. Miyamoto said he could. Yamauchi appointed Nintendo's head engineer, Gunpei Yokoi, to supervise the project. Miyamoto came up with many characters and plot concepts, but he eventually settled on a gorilla/carpenter/girlfriend love triangle that mirrored the rivalry between Bluto and Popeye for Olive Oyl. Bluto became an ape, which Miyamoto said was "nothing too evil or repulsive". He would be the pet of the main character, "a funny, hang-loose kind of guy." Miyamoto has also named "Beauty and the Beast" and the 1933 film King Kong as influences. Although its origin as a comic strip license played a major part, Donkey Kong marked the first time that the storyline for a video game preceded the game's programming rather than simply being appended as an afterthought. Miyamoto had high hopes for his new project. He lacked the technical skills to program it himself, so instead came up with concepts and consulted technicians to see if they were possible. He wanted to make the characters different sizes, move in different manners and react in various ways. Yokoi thought Miyamoto's original design was too complex. Another idea Yokoi suggested was to use see-saws to catapult the hero across the screen; this was too difficult to program. Miyamoto then thought of using sloped platforms, barrels and ladders. When he specified that the game would have multiple stages, the four-man programming team complained that he was essentially asking them to make the game repeatedly. The game was sent to Nintendo of America for testing. The sales manager hated it for being too different from the maze and shooter games common at the time, and Judy and Lincoln expressed reservations over the strange title. Still, Arakawa swore that it would be big. American staffers asked Yamauchi to change the name, but he refused. Arakawa and the American staff began translating the storyline for the cabinet art and naming the other characters. They chose "Pauline" for the Lady, after Polly James, wife of Nintendo's Redmond, Washington, warehouse manager, Don James. Jumpman was eventually named for Mario Segale, the warehouse landlord. These character names were printed on the American cabinet art and used in promotional materials. Donkey Kong was ready for release.

Donkey Kong was a succes, Miyamoto worked on the sequels Donkey Kong Jr. and Donkey Kong 3, both bringing back some elements from the original. He later worked on other Nintendo titles like Excitebike and Devil World. His next game was based on the character from Donkey Kong, Jumpman which became Mario and his brother Luigi called Mario Bros.. In Donkey Kong, Mario dies if he falls too far. Yokoi suggested to Miyamoto that he would be able to fall from any height, which Miyamoto was not sure of, thinking that it would make it "not much of a game." He eventually agreed, thinking it would be okay for him to have some super-human abilities. Because of Mario's appearance in Donkey Kong, with overalls, a hat, and a thick moustache, Miyamoto thought that he should be a plumber as opposed to a carpenter, and designed this game to reflect that. Miyamoto also felt that the best setting for this game was New York because of its "labyrinthine subterranean network of sewage pipes. The two-player mode and several aspects of gameplay were inspired by an earlier video game called Joust. To date, Mario Bros. has been released for more than a dozen platforms.

1985-1990

After Mario Bros. Miyamoto worked on diffrent games includeing Ice Climber and Kid Icarus alongside his old friend Gunpei Yokoi. He later made another game based on Mario called Super Mario Bros. which was a great succeses gaining a lot of great reception. It also popularized the side scrolling genre of video games, the game has sold 40.24 million copies, making it the best-selling video game in the Mario series. Soon Miyamoto would create another game called The Legend of Zelda, in Mario, Miyamoto downplayed the importance of the high score in favor of simply completing the game. This concept was carried over to The Legend of Zelda. Miyamoto was also in charge of deciding which concepts were "Zelda ideas" or "Mario ideas." Contrasting with Mario, Zelda was made non-linear and forced the players to think about what they should do next with riddles and puzzles. With The Legend of Zelda, Miyamoto wanted to take the idea of a game "world" even further, giving players a "miniature garden that they can put inside their drawer." He drew his inspiration from his experiences as a boy around Kyoto, where he explored nearby fields, woods, and caves, and through the Zelda titles he always tries to impart to players some of the sense of exploration and limitless wonder he felt. "When I was a child," he said, "I went hiking and found a lake. It was quite a surprise for me to stumble upon it. When I traveled around the country without a map, trying to find my way, stumbling on amazing things as I went, I realized how it felt to go on an adventure like this." The memory of being lost amid the maze of sliding doors in his family's home in Sonobe was recreated in Zelda's labyrinthine dungeons. In February 1986, Nintendo released the game as the launch title for the Family Computer's new Disk System peripheral. The Legend of Zelda was joined by a re-release of Super Mario Bros. and Tennis, Baseball, Golf, Soccer, and Mahjong in its introduction of the Disk System. It made full use of the "disk card" media's advantages over traditional ROM cartridges with a disk size of 128 kilobytes, which was expensive to produce on cartridge format. Due to the still-limited amount of space on the disk, however, the Japanese version of the game was only in katakana. It used rewritable disks to save the game, rather than passwords. The Japanese version used the extra sound channel provided by the Disk System for certain sound effects; most notable are the sounds of Link's sword when his health is full, and enemy death sounds. The sound effects used the NES's PCM channel in the cartridge version. It also used the microphone built into the Famicom's controller that was not included in the NES. The Legend of Zelda was a bestseller for Nintendo, selling over 6.5 million copies.

Personal life

Although a game designer, Miyamoto spends little time playing games, preferring to play the guitar and banjo. He has a Shetland Sheepdog named Pikku that was the inspiration for Nintendogs. He is also a semi-professional dog breeder.. He has been quoted as stating, "Video-games are bad for you? That's what they said about Rock 'N' Roll." Miyamoto also has stated that he has a hobby of guessing the measurements of objects, then checking to see if he was correct, and apparently carries a tape measure with him everywhere. He has a wife and two children, and owns a cat.

Awards and recognition

The name of the main character of the PC game Daikatana, Hiro Miyamoto, is an homage to Miyamoto.

The character Gary Oak from the Pokémon anime series is named Shigeru in Japan and is the rival of Ash Ketchum (called Satoshi in Japan). Pokémon creator Satoshi Tajiri was mentored by Shigeru Miyamoto.

In 1998, Miyamoto was honored as the first person inducted into the Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences' Hall of Fame.

In 2006, Miyamoto was made a Chevalier (knight) of the French Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Minister of Culture Renaud Donnedieu de Vabres.

On November 28, 2006, Miyamoto was featured in TIME Asia's "60 Years of Asian Heroes," alongside Hayao Miyazaki, Mahatma Gandhi, Mother Teresa, Bruce Lee and the Dalai Lama. He was later chosen as one of Time Magazine's 100 Most Influential People of the Year in both 2007 and also in 2008, in which he topped the list with a total vote of 1,766,424.

At the Game Developers Choice Awards, on March 7, 2007, Miyamoto received the Lifetime Achievement Award "for a career that spans the creation of Donkey Kong, Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda to the company's recent revolutionary systems, Nintendo DS and Wii."

Both GameTrailers and IGN placed Miyamoto first on their lists for the "Top Ten Game Creators" and the "Top 100 Game Creators of All Time" respectively.

In a survey of game developers by industry publication Develop, 30% of the developers chose Miyamoto as their "Ultimate Development Hero". Miyamoto has been interviewed by companies and organizations such as CNN's Talk Asia and NextLevel.com.

Selected gameography

Main article: List of Nintendo games created by Shigeru Miyamoto| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Shigeru Miyamoto" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Donkey Kong (1981)

- Mario Bros. (1983)

- Super Mario Bros. (1985)

- Super Mario Bros. 2 (1986)

- The Legend of Zelda (1987)

- Super Mario Bros. 3 (1988)

- The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past (1991)

- Super Mario Kart (1992)

- Super Mario 64 (1996)

- The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998)

- The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask (2000)

- Super Smash Bros. Melee (2001)

- Super Mario Sunshine (2002)

- Metroid Prime (2002)

- The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker (2002)

- Super Mario Galaxy (2007)

- Super Smash Bros. Brawl (2008)

- New Super Mario Bros. Wii (2009)

- Super Mario Galaxy 2 (2010)

See also

References

- ^ Nintendo Power staff (1997). Star Fox 64 Player's Guide. Nintendo of America. pp. 116–119.

- Nintendo Power staff (June 2007). "Power Profiles 1: Shigeru Miyamoto". Nintendo Power (216): 88–90.

- ^ Wright, Will. "Shigeru Miyamoto: The video-game guru who made it O.K. to play". TIME Magazine. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- Vestal, Andrew; et al. (14 September 2000). "History of Zelda". GameSpot. Retrieved 30 September 2006.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Sheff, David (1993). Game Over. Random House. ISBN 0-679-40469-4.

- http://us.wii.com/iwata_asks/punchout/vol1_page2.jsp

- Kent 157.

- Kent 158.

- Cite error: The named reference

Kohler 39was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Both quotes from Sheff 47.

- Kohler 36.

- Kohler 38.

- Sheff 47–48.

- Kohler 38–39.

- Sheff 49.

- Cite error: The named reference

Kent 159was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Sheff 109.

- Kohler 212.

- "IGN Presents The History of Super Mario Bros". IGN.com. 2007-11-08. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- Fox, Matt (2006). The Video Games Guide. Boxtree Ltd. pp. 261–262. ISBN 0752226258.

- Eric Marcarelli. "Every Mario Game". Toad's Castle. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- "Super Mario Sales Data: Historical Unit Numbers for Mario Bros on NES, SNES, N64..." GameCubicle.com. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ Vestal, Andrew (2000-11-14). "History of Zelda". GameSpot. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Bufton, Ben (2005-01-01). "Shigeru Miyamoto Interview". ntsc-uk. Retrieved 2006-09-23.

- Sheff (1993), p. 51

- Sheff (1993), p. 52

- Edwards, Benj (2008-08-07). "Inside Nintendo's Classic Game Console". PC World. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - "March 25, 2004". The Magic Box. 2004-03-25. Archived from the original on 2005-11-26. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- "Shigeru Miyamoto Developer Bio". MobyGames. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- Totilo, Stephen (27 September 2005). "Nintendo Fans Swarm Mario's Father During New York Visit". VH1. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- Gibson, Ellie (23 August 2005). "Nintendogs Interview // DS // Eurogamer". Eurogamer. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- http://thinkexist.com/quotation/video-games-are-bad-for-you-that-s-what-they-said/406209.html

- http://kotaku.com/5381876/miyamotos-secret-hobby-measuring-stuff

- "A Hardcore Elegy for Ion Storm". Salon.com. p. 5. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- "Miyamoto Will Enter Hall of Fame". GameSpot. 12 May 1998. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- "Le jeu vidéo distingué par la République". Gamekult. 13 March 2006. Retrieved 25 August 2009. Template:Fr icon

- François Bliss de la Boissière (15 March 2006). "From Paris with Love: de Chevalier dans l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres". Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- Wendel, Johnathan. "The TIME 100 (2007) – Shigeru Miyamoto". TIME Magazine. Retrieved 3 May 2007.

- "Who is Most Influential? – The 2008 TIME 100 Finalists". TIME Magazine. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- Carless, Simon (12 February 2007). "2007 Game Developers Choice Awards To Honor Miyamoto, Pajitnov". Gamasutra. Retrieved 12 February 2007.

- GT Countdown Video Game, Top Ten Game Creators | Game Trailers & Videos | GameTrailers.com

- IGN – 1. Shigeru Miyamoto

- http://www.escapistmagazine.com/news/view/92401-Miyamoto-Is-Developers-Hero

- http://www.cnn.com/2007/WORLD/asiapcf/02/14/miyamoto.script/index.html

- http://www.the-nextlevel.com/feature/interview-shigeru-miyamoto/

- http://www.allgame.com/game.php?id=410&tab=credits

- http://www.gamespot.com/arcade/action/masao/tech_info.html?tag=tabs;summary

- http://www.allgame.com/game.php?id=1320&tab=credits

- http://www.allgame.com/game.php?id=248&tab=credits

- http://www.allgame.com/game.php?id=1002&tab=credits

- E3: Through the Eyes of Miyamoto Pt. 2. IGN. 18 June 1997.

- http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0879874

External links

- N-Sider – Shigeru Miyamoto profile

- Shigeru Miyamoto profile on MobyGames

- New York Times profile, May 25, 2008

- Video profile of Shigeru Miyamoto from the digital TV series Play Value produced by ON Networks