This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Humus sapiens (talk | contribs) at 05:01, 23 January 2006 (timeframe: 19th century, place: Palestine province of the Ottoman Empire). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 05:01, 23 January 2006 by Humus sapiens (talk | contribs) (timeframe: 19th century, place: Palestine province of the Ottoman Empire)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article is currently under extended confirmed protection. Extended confirmed protection prevents edits from all unregistered editors and registered users with fewer than 30 days tenure and 500 edits. The policy on community use specifies that extended confirmed protection can be applied to combat disruption, if semi-protection has proven to be ineffective. Extended confirmed protection may also be applied to enforce arbitration sanctions. Please discuss any changes on the talk page; you may submit an edit request to ask for uncontroversial changes supported by consensus. |

Jews (Hebrew: יהודים translit.: Yehudim) are followers of Judaism or, more generally, members of the Jewish people (also known as the Jewish nation, or the Children of Israel), an ethno-religious group descended from the ancient Israelites and converts who joined their religion at various times and places. In this broader sense, Jews may or may not be religiously observant. This article discribes some ethnic, historic and cultural aspects of the Jewish identity; for a consideration of Jewish religion, refer to the article Judaism.

At least for three thousand years, the Jewish people have lived in the Land of Israel, where they developed a monotheistic religion and enjoyed periods of self-determination. As a result of foreign conquests and expulsions, the Jewish diaspora has formed. Most of the Jews were expelled from their national homeland by the Romans in the year 135 and since then had a troubled existence surviving discrimination, oppression, poverty and even extermination (see article Anti-Semitism), but sometimes also cultural, economic and individual prosperity.

Throughout the years the Jewish religion, Judaism, was the prime binding factor among the Jews, although it was not strictly required to be followed in order to belong to the Jewish people. Since the rise of modern nationalism and other changes among the peoples around in the 19th century, Jews too have undergone a transition, as a result of which gradually more people saw themselves as an ethnic or etno-religious community within the nations around. Participation in all aspects of social life could now increase. Particularly from Eastern and Central Europe, where antisemitism was worst, a Jewish national movement had evolved, Zionism, that contributed to the growth of the Jewish population in the Land of Israel, at that time Palestine province of the Ottoman Empire, later the British Mandate of Palestine and eventually to the foundation of the State of Israel.

The Hebrew name Yehudi (plural Yehudim) came into being when the Kingdom of Israel was split between the northern Kingdom of Israel and the southern Kingdom of Judah. The term originally referred to the people of the southern kingdom, although the term Bnei Yisrael (Israelites) was still used for both groups. After the Assyrians conquered the northern kingdom leaving the southern kingdom as the only Israelite state, the word Yehudim gradually came to refer to people of the Jewish faith as a whole, rather than those specifically from Judah. The English word Jew is ultimately derived from Yehudi (see Etymology). Its first use in the Bible to refer to the Jewish people as a whole is in the Book of Esther. In modern usage, Jews include both those Jews actively practicing Judaism, and those Jews who, while not practicing Judaism as a religion, still identify themselves as Jews by virtue of their family's Jewish heritage and their own cultural identification.

Usage note

Some uses of the term "Jew" are tainted by historic anti-Jewish bigotry. The correct adjectival form is "Jewish"; the use of "Jew" as an adjective (as in "Jew lawyer" rather than "Jewish lawyer") is associated with bigotry. The use of "Jew" or "jew" as a verb (as in "to jew someone down": to bargain for a lower price) is generally seen as an extremely offensive expression based on stereotypes.

Even when used in a grammatically correct manner as a noun, the term "Jew" has been used to objectify and separate Jews from the remainder of the population, often by referring to the majority population by the name of the country ("Countrymen") but referring to Jewish citizens as "Jews."

Etymology

Main article: Etymology of the word JewThere are different views as to the origin of the English language word Jew. The most common view is that the Middle English word Jew is from the Old French giu, earlier juieu, from the Latin iudeus from the Greek Ioudaios (Ιουδαίος). The Latin simply means Judaean, from the land of Judaea. The Hebrew for Jew, יהודי , is pronounced ye-hoo-DEE. The Hebrew letter Yodh (or Yud), י, used as a 'y' in the Hebrew language (as in the word ye-hoo-DEE), becomes a 'j' in languages using the Latin-based alphabet when the Yodh is used as a consonant rather than as a vowel. Therefore, a rough transliteration of יהודי in English would be Jew.

The etymological equivalent is in use in other languages, e.g., "Jude" in German, "jøde," in Norwegian, etc., but derivations of the word "Hebrew" is also in use to describe a Jewish person, e.g., in Italian (Ebrei) and Template:Lang-ru, (Yevrey). (See Names of the Jewish people for a full overview.)

Who is a Jew?

Main article: Who is a Jew?

Judaism shares some of the characteristics of a nation, an ethnicity, a religion, and a culture, making the definition of who is a Jew vary slightly depending on whether a religious or national approach to identity is used. For discussions of the religious views on who is a Jew and how these views differ from each other, please see Who is a Jew?. Generally, in modern secular usage, Jews include three groups: people who practice Judaism and have a Jewish ethnic background (sometimes including those who do not have strictly matrilineal descent), people without Jewish parents who have converted to Judaism; and those Jews who, while not practicing Judaism as a religion, still identify themselves as Jewish by virtue of their family's Jewish descent and their own cultural and historical identification with the Jewish people.

Historical definitions of Jewish identity have traditionally been based on Halakhic definitions of matrilineal descent, and halachic conversions. Historical definitions of who is a Jew date back to the codification of the oral traditon into the Babylonian Talmud. Biblical interpertations of sections in the Tanach, such as Deuteronomy 7:1-5, by learned Jewish sages, is used as a warning against intermarriage between Jews and non Jews because " will cause your child to turn away from Me and they will worship the gods of others." Leviticus 24:10 speaks of the son in a marriage between a Hebrew woman and an Egyptian man to be "of the community of Israel.", which contrasts with Ezra 10:2-3, where Israelites returning from Egypt, vowed to put aside their gentile wives and their children. Since the Haskalah, these halakhic interpretations of Jewish identity have been challenged.

Jewish culture

Secular Jewish culture Main article: JudaismJudaism guides its adherents in both practice and belief, and has been called not only a religion, but also a "way of life," which has made drawing a clear distinction between Judaism, Jewish culture, and Jewish nationality rather difficult. In many times and places, such as in the ancient Hellenic world, in Europe before and after the Enlightenment (see Haskalah), and in contemporary United States and Israel, cultural phenomena have developed that are in some sense characteristically Jewish without being at all specifically religious. Some factors in this come from within Judaism, others from the interaction of Jews with others around them, others from the inner social and cultural dynamics of the community, as opposed to religion itself.

Ethnic divisions

Main article: Jewish ethnic divisionsThe most commonly used terms to describe ethnic divisions among Jews currently are: Ashkenazi (meaning "German" in Hebrew, denoting the Central European base of Jewry); and Sephardi (meaning "Spanish" or "Iberia" in Hebrew, denoting their Spanish, Portuguese and North African location). They refer to both religious and ethnic divisions.

Other Jewish ethnic groups include Mizrahi Jews (a term overlapping Sephardi, but emphasizing North African and Middle Eastern rather than Spanish history, and including the Maghrebim); Teimanim (Yemenite and Omani Jews); and such smaller groups as the Gruzim and Juhurim from the Caucasus, the Bene Israel, Bnei Menashe, Cochin and Telugu Jews of India, the Romaniotes of Greece, the Italkim (Bené Roma) of Italy, various African Jews (most notably the Beta Israel or Ethiopian Jews), the Bukharan Jews of Central Asia, and the Persian Jews of Iran.

Population

Main article: Jewish populationPrior to World War II the world population of Jews was approximately 18 million. The Holocaust reduced this number to approximately 12 million. Today, there are an estimated 13 million to 14.6 million Jews worldwide in over 134 countries.

Significant geographic populations

Main article: Jews by countryPlease note that these populations represent low-end estimates of the worldwide Jewish population, accounting for around 0.2% of the world's population. Higher estimates place the worldwide Jewish population at over 14.5 million.

| Country or Region | Jewish population | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 5,671,000 | (est.) |

| Israel | 5,300,000 | (est.) (about 76% of Israel's population) |

| Europe | 2,000,000 | (fewer than) |

| France | 600,000 | (est.) |

| Russia | 400,000 | (Territory of the former Soviet Union. Some estimates are much higher.) |

| United Kingdom | 267,000 | (2001 census) |

| Germany | 100,000 | (2004 est.) or 60,000 (est.) |

| Turkey | 30,000 | (2001 census) |

| Italy | 30,000 | (Jewish communities est.) |

| Canada | 371,000 | (est.) |

| Argentina | 250,000 | (est.) |

| Brazil | 130,000 | (est.) |

| South Africa | 106,000 | (est.) |

| Australia | 100,000 | (est.) |

| Asia (excl. Israel) | 50,000 | (est.) |

| Mexico | 40,000–50,000 | (est.) |

| Iran | 11,000 | (est.) |

| Total | 15,471,000 | (est.) |

State of Israel

Main article: Israel

Israel, the Jewish nation-state, is the only country in which Jews make up a majority of the citizens. It was established as an independent democratic state on May 14, 1948. Of the 120 members in its parliament, the Knesset, 9 members are Israeli Arabs and 2 are Israeli Druses. At the time of its independence, approximately 600,000 Jews lived in Israel. Since then, the country's Jewish population has increased by about one million over each decade as more immigrants arrived and more Israelis were born, resulting in one of the most significant global Jewish population shifts in over 2,000 years.

All the Arab Israeli Wars have not slowed Israel's growth. Israel opened its doors to the Holocaust survivors. It has absorbed a majority of the Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews from the Islamic countries. It has taken in hundreds of thousands of Jews from the former USSR, and has airlifted tens of thousands of Ethiopian Jewsto Israel. In the past decade nearly a million immigrants came to Israel from the former Soviet Union. Many Jews who emigrated to Israel have moved elsewhere, known as yerida ("descent" ), due to its economic problems or due to disillusionment with political conditions and the continuing Israeli-Palestinian conflict

Diaspora (outside Israel)

Main article: Jewish diasporaThe waves of immigration to the United States at the turn of the 19th century, massacre of European Jewry during the Holocaust, and the foundation of the state of Israel (and subsequent Jewish exodus from Arab lands) all resulted in substantial shifts in the population centers of world Jewry during the 20th century.

Currently, the largest Jewish community in the world is located in the United States, with around 5.6 million Jews. Elsewhere in the Americas, there are also large Jewish populations in Canada and Argentina, and smaller populations in Brazil, Mexico , Uruguay, Venezuela, Chile, and several other countries (see History of the Jews in Latin America).

Western Europe's largest Jewish community can be found in France, home to 600,000 Jews, the majority of whom are immigrants or refugees from North African Arab countries such as Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia (or their descendants). There are over 265,000 Jews in the United Kingdom. In Eastern Europe, there are anywhere from 500,000 to over two million Jews living in Russia, Ukraine, Hungary, Belarus and the other areas once dominated by the Soviet Union, but exact figures are difficult to establish. The fastest-growing Jewish community in the world, outside Israel, is the one in Germany, especially in Berlin, its capital. Tens of thousands of Jews from the former Eastern Bloc have settled in Germany since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The Arab countries of North Africa and the Middle East were home to around 900,000 Jews in 1945. Systematic persecution after the founding of Israel caused almost all of these Jews to flee to Israel, North America, and Europe in the 1950s. Today, around 8,000 Jews remain in Arab nations. Iran is home to around 25,000 Jews, down from a population of 100,000 Jews before the 1979 revolution. After the revolution some of the Iranian Jews emigrated to Israel or Europe but most of them emigrated (with their non-Jewish Iranian compatriots) to the United States (especially Los Angeles).

Outside Europe, Asia and the Americas, significant Jewish populations exist in Australia and South Africa.

Population changes: Assimilation

Since at least the time of the ancient Greeks, a proportion of Jews have assimilated into the wider non-Jewish society around them, by either choice or force, ceasing to practice Judaism and losing their Jewish identity. Some Jewish communities, for example the Kaifeng Jews of China, have disappeared entirely, but assimilation has remained relatively low over much of the past millennium, as Jews were often not allowed to integrate with the wider communities in which they lived. The advent of the Jewish Enlightenment (see Haskalah) of the 1700s and the subsequent emancipation of the Jewish populations of Europe and America in the 1800s, changed the situation, allowing Jews to increasingly participate in, and become part of, secular society. The result has been a growing trend of assimilation, as Jews marry non-Jewish spouses and stop participating in the Jewish community. Rates of interreligious marriage vary widely: In the United States they are just under 50%, in the United Kingdom around 50%, and in Australia and Mexico as low as 10%, and in France they may be as high as 75%. In the United States, only about a third of children from intermarriages affiliate themselves with Jewish practice. Additionally, since non-religious Jews generally tend to marry later and have fewer children than the general population, the Jewish community in many countries is aging. The result is that most countries in the Diaspora have steady or slightly declining Jewish populations as Jews continue to assimilate into the countries in which they live.

Population changes: Wars against the Jews

Throughout history, many rulers, empires and nations have oppressed their Jewish populations, or sought to eliminate them entirely. Methods employed have ranged from expulsion to outright genocide; within nations, often the threat of these extreme methods was sufficient to silence dissent. Some examples in the history of anti-Semitism are: the Great Jewish Revolt against the Roman Empire; the First Crusade which resulted in the massacre of Jews; the Spanish Inquisition led by Torquamada and the Auto de fe against the Marrano Jews; the Bohdan Chmielnicki Cossack massacres in Ukraine; the Pogroms backed by the Russian Tsars; as well as expulsions from Spain, England, France, Germany, and other countries in which the Jews had settled. The persecution culminated in Adolf Hitler's Final Solution which led to the Holocaust, and the slaughter of approximately 6 million Jews from 1939 to 1945.

Population changes: Growth

Israel is the only country with a consistently growing Jewish population due to natural population increase, though the Jewish populations of other countries in Europe and North America have recently increased due to immigration. In the Diaspora, in almost every country the Jewish population in general is either declining or steady, but Orthodox and Haredi Jewish communities, whose members often shun birth control for religious reasons, have experienced rapid population growth, with rates near 4% per year for Haredi Jews in Israel, and similar rates in other countries.

Orthodox and Conservative Judaism discourage proselytization to non-Jews, but many Jewish groups have tried to reach out to the assimilated Jewish communities of the Diaspora in order to increase the number of Jews. Additionally, while in principle Reform Judaism favors seeking new members for the faith, this position has not translated into active proselytism, instead taking the form of an effort to reach out to non-Jewish spouses of intermarried couples. There is also a trend of Orthodox movements pursuing secular Jews in order to give them a stronger Jewish identity so there is less chance of intermarriage. As a result of the efforts by these and other Jewish groups over the past twenty-five years, there has been a trend of secular Jews becoming more religiously observant, known as the Baal Teshuva movement, though the demographic implications of the trend are unknown. Additionally, there is also a growing movement of Jews by Choice by gentiles who make the decision to head in the direction of becoming Jews.

Jewish languages

Main article: Jewish languagesHebrew is the liturgical language of Judaism (termed lashon ha-kodesh, "the holy tongue"), and is the language of the State of Israel. It was revived by Eliezer ben Yehuda, who arrived in Palestine in 1881 at a time when no one spoke the Hebrew language. Diaspora Jews (outside Israel) today speak the local languages of their respective countries. Yiddish is the historic language of many Ashkenazi Jews, and Ladino of many Sephardic Jews.

History of the Jews

Main article: Jewish history Main article: Timeline of Jewish history- See also: Historical Schisms among the Jews

Jews and migrations

Throughout Jewish history, Jews have repeatedly been directly or indirectly expelled from both their original homeland, and the areas in which they have resided. This experience as both immigrants and emigrants (see: Jewish refugees) have shaped Jewish identity and religious practice in many ways. An incomplete list of such migrations includes:

- The patriarch Abraham was a migrant to the land of Canaan from Ur of the Chaldees.

- The Children of Israel experienced the Exodus (meaning "departure" or "going forth" in Greek) from ancient Egypt, as recorded in the Book of Exodus.

- The Kingdom of Israel was sent into permanent exile and scattered all over the world by Assyria.

- The Kingdom of Judah was exiled first by Babylonia and then by Rome.

- The 2,000 year dispersion of the Jewish diaspora beginning under the Roman Empire, as Jews were spread throughout the Roman world and, driven from land to land, and settled wherever they could live freely enough to practice their religion. Over the course of the diaspora the center of Jewish life moved from Babylonia to Spain to Poland to the United States and to Israel.

- Many expulsions during the Middle Ages and Enlightenment in Europe, including: 1290, 16,000 Jews were expelled from England, see the (Statute of Jewry); in 1396, 100,000 from France; in 1421 thousands were expelled from Austria. Many of these Jews settled in Eastern Europe, especially Poland.

- Following the Spanish Inquisition in 1492, the Spanish population of around 200,000 Sephardic Jews were expelled by the Spanish crown and Catholic church, followed by expulsions in 1493 in Sicily (37,000 Jews) and Portugal in 1496. The expelled Jews fled mainly to the Ottoman Empire, the Netherlands, and North Africa, others migrating to Southern Europe and the Middle East.

- During the 19th century, France's policies of equal citizenship regardless of religion led to the immigration of Jews (especially from Eastern and Central Europe), which was encouraged by Napoleon Bonaparte.

- The arrival of millions of Jews in the New World, including immigration of over two million Eastern European Jews to the United States from 1880-1925, see History of the Jews in the United States and History of the Jews in Russia and the Soviet Union.

- The Pogroms in Eastern Europe, the rise of modern Anti-Semitism, the Holocaust and the rise of Arab nationalism all served to fuel the movements and migrations of huge segments of Jewry from land to land and continent to continent, until they have now arrived back in large numbers at their original historical homeland in Israel.

- The Islamic Revolution of Iran, forced many Iranian Jews to flee Iran. Most found refuge in the US (particularly Los Angeles, CA) and Israel. Smaller communities of Persian Jews exist in Canada and Western Europe.

Kingdoms of Israel and Judah

Jews descend mostly from the ancient Israelites (also known as Hebrews), who settled in the Land of Israel. The Israelites traced their common lineage to the biblical patriarch Abraham through Isaac and Jacob. A kingdom was established under Saul and continued under King David and Solomon. King David conquered Jerusalem (first a Canaanite, then a Jebusite town) and made it his capital. After Solomon's reign the nation split into two kingdoms, the Kingdom of Israel (in the north) and the Kingdom of Judah (in the south). The Kingdom of Israel was conquered by the Assyrian ruler Shalmaneser V in the 8th century BC and spread all over the Assyrian empire, where they were assimilated into other cultures and become known as the Ten Lost Tribes. The Kingdom of Judah continued as an independent state until it was conquered by a Babylonian army in the early 6th century BC, destroying the First Temple that was at the centre of Jewish worship. The Judean elite was exiled to Babylonia, but later at least a part of them returned to their homeland after the subsequent conquest of Babylonia by the Persians seventy years later, a period known as the Babylonian Captivity. A new Second Temple was constructed funded by Persian Kings, and old religious practices were resumed.

Persian, Greek, and Roman rule

- See related article Jewish-Roman wars.

The Seleucid Kingdom, which arose after the Persians were defeated by Alexander the Great, sought to introduce Greek culture into the Persian world. When the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes, supported by Hellenized Jews (those who had adopted Greek culture), attempted to convert the Jewish Temple to a temple of Zeus, the non-Hellenized Jews revolted under the leadership of the Maccabees and rededicated the Temple to the Jewish God (hence the origins of Hanukkah) and created an independent Jewish kingdom known as the Hasmonaean Kingdom which lasted from 165 BCE to 63 BCE, when the kingdom came under influence of the Roman Empire. During the early part of Roman rule, the Hasmonaeans remained in power, until the family was annihilated by Herod the Great. Herod came from a wealthy Idumean family and became a very successful client-king under the Romans. He significantly expanded the Temple in Jerusalem.

Upon his death in 4 BCE the Romans directly ruled Judea and there were frequent changes of policies by conflicting and empire-building Caesars, generals, governors, and consuls who often acted cruelly or to maximize their own wealth and power. Rome's attitudes swung from tolerance to hostility against its Jewish subjects, who had since moved throughout the Empire. The Romans, worshipping a large pantheon, could not readily accommodate the exclusive monotheism of Judaism, and the religious Jews could not accept Roman polytheism. After a famine and riots in 66 CE, the Judeans began to revolt against their Roman rulers. The revolt was smashed by the Roman emperors Vespasian and Titus Flavius. In Rome the Arch of Titus still stands, showing enslaved Judeans and a menorah being brought to Rome. It is customary for Jews not to walk through this arch.

The Romans all but destroyed Jerusalem; only a single "Western Wall" of the Second Temple remained. After the end of this first revolt, the Judeans continued to live in their land in significant numbers, and were allowed to practice their religion. In the second century the Roman Emperor Hadrian began to rebuild Jerusalem as a pagan city while restricting some Jewish practices. Angry at this affront, the Judeans again revolted led by Simon Bar Kokhba. Hadrian responded with overwhelming force, putting down the revolution and killing as many as half a million Jews. After the Roman Legions prevailed in 135, Jews were not allowed to enter the city of Jerusalem and most Jewish worship was forbidden by Rome. Following the destruction of Jerusalem and the expulsion of the Jews, Jewish worship stopped being centrally organized around the Temple, and instead was rebuilt around rabbis who acted as teachers and leaders of individual communities. No new books were added to the Jewish Bible after the Roman period, instead major efforts went into interpreting and developing the Halakhah, or oral law, and writing down these traditions in the Talmud, the key work on the interepretation of Jewish law, written during the first to fifth centuries CE.

Beginning of the Diaspora

Main article: Jewish diasporaThough Jews had settled outside Israel since the time of the Babylonians, the results of the Roman response to the Jewish revolt shifted the center of Jewish life from its ancient home to the diaspora. While some Jews remained in Judea, renamed Palestine by the Romans, some Jews were sold into slavery, while others became citizens of other parts of the Roman Empire. This is the traditional explanation to the Jewish diaspora, almost universally accepted by past and present rabbinical or Talmudical scholars, who believe that Jews are almost exclusively biological descendants of the Judean exiles, a belief backed up at least partially by DNA evidence. Some secular historians speculate that a majority of the Jews in Antiquity were most likely descendants of converts in the cities of the Graeco-Roman world, especially in Alexandria and Asia Minor. They were only affected by the diaspora in its spiritual sense and by the sense of loss and homelessness which became a cornerstone of the Jewish creed, much supported by persecutions in various parts of the world. Any such policy of conversion, which spread the Jewish religion throughout Hellenistic civilization, seems to have ended with the wars against the Romans and the following reconstruction of Jewish values for the post-Temple era. DNA evidence of this theory has been spotty, however, some historians believe based on some historical records that at the dawn of Christianity as many as 10% of the population of the Roman Empire were Jewish, a figure that could only be explained by local conversion. This theory could also solve the paradox of DNA studies noted above that show Ashkenazi Jews to be closely related to the peoples of the nations surrounding Israel despite physical features that more closely resembles that of the peoples of southern and central Europe; as one explanation would be a large miscegenation millenia ago followed by almost no outside genetic contact thereafter.

During the first few hundred years of the Diaspora, the most important Jewish communities were in Babylonia, where the Talmud was written, and where relatively tolerant regimes allowed the Jews freedom. The situation was worse in the Byzantine Empire which treated the Jews much more harshly, refusing to allow them to hold office or build places of worship. The conquest of much of the Byzantine Empire and Babylonia by Islamic armies generally improved the life of the Jews, though they were still considered second-class citizens. In response to these Islamic conquests, the First Crusade of 1096 attempted to reconquer Jerusalem, resulting in the destruction of many of the remaining Jewish communities in the area.

Middle Ages: Europe

Main article: Jews in the Middle Ages

Jews settled in Europe during the time of the Roman Empire, but the rise of the Catholic Church resulted in frequent expulsions and persecutions. The Crusades routinely attacked Jewish communities, and increasingly harsh laws restricted them from most economic activity and land ownership, leaving open only moneylending and a few other trades. Jews were subject to explusions from England, France, and the Holy Roman Empire throughout the Middle Ages, with most of the population moving to Eastern Europe and especially Poland, which was uniquely tolerant of the Jews through the 1700s. The final mass expulsion of the Jews, and the largest, occurred after the Christian conquest of Spain in 1492 (see History of the Jews in Spain). Even after the end of the expulsions in the 17th century, individual conditions varied from country to country and time to time, but, as rule, Jews in Western Europe generally were forced, by decree or by informal pressure, to live in highly segregated ghettos and shtetls.

Middle Ages: Islamic Europe and North Africa

Main article: Islam and JudaismDuring the Middle Ages, Jews in Islamic lands generally had more rights than under Christian rule, with a Golden Age of coexistence in Islamic Spain from about 900 to 1200, when Spain became the center of the richest, most populous, and most influential Jewish community of the time. The rise of more radical Muslim regimes, such as that of the Almohades ended this period by the thirteenth century, and Jews were soon expelled from Spain. Many of these Jews found refuge in the Ottoman Empire, which remained tolerant of its Jewish population for much of its history.

Enlightenment and emancipation

Main article: HaskalahDuring the Age of Enlightenment, significant changes occurred within the Jewish community. The Haskalah movement paralleled the wider Enlightenment, as Jews began in the 1700s to campaign for emancipation from restrictive laws and integration into the wider European society. Secular and scientific education was added to the traditional religious instruction received by students, and interest in a national Jewish identity, including a revival in the study of Jewish history and Hebrew, started to grow.

The Haskalah movement influenced the birth of all the modern Jewish denominations, and planted the seeds of Zionism. At the same time, it contributed to encouraging cultural assimilation into the countries in which Jews resided. At around the same time another movement was born, one preaching almost the opposite of Haskalah, Hasidic Judaism. Hasidic Judiasm began in the 1700s by Israel ben Eliezer, the Baal Shem Tov, and quickly gained a following with its exuberant, mystical approach to religion. These two movements, and the traditional orthodox approach to Judaism from which they spring, formed the basis for the modern divisions within Jewish observance.

At the same time, the outside world was changing. France was the first country to emancipate its Jewish population in 1796, granting them equal rights under the law. Napoleon further spread emancipation, inviting Jews to leave the Jewish ghettos in Europe and seek refuge in the newly created tolerant political regimes (see Napoleon and the Jews). By the mid-19th century, almost all Western European countries had emancipated their Jewish populations, with the notable exception of the Papal States, but persecution continued in Eastern Europe, including massive pogroms at the end of the 19th century throughout the Pale of Settlement. The persistence of anti-semitism, both violently in the east and socially in the west, led to a number of Jewish political movements, culminating in Zionism.

Zionism and immigration

Many of the newly secular Jews who had embraced Haskalah found themselves deeply troubled by the continuing virulent anti-semitism of the late 1800s, especially the massive pogroms of the 1880s in Russia and the Dreyfus Affair, which occurred in France in 1894, a country many Jews had previously thought of as particularly accepting. Many Jews in Eastern Europe embraced socialism as a potential escape from persecution, but another group, the Zionists, led by Theodor Herzl, viewed the only solution as the creation of a Jewish state. Initially, religious Jews opposed Zionism, as did many secular Jews, who saw integration or other social movements as more promising. The chain of events between 1881 and 1945, however, beginning with waves of anti-Semitic pogroms in Russia and the Russian-controlled areas of Poland, and culminating in the Holocaust, converted the great majority of surviving Jews to the belief that a Jewish homeland was an urgent necessity, particularly given the large population of disenfranchised Jewish refugees after World War II.

In addition to responding politically, during the late 19th century, Jews began to flee the persecutions of Eastern Europe in large numbers, mostly by heading to the United States, but also to Canada and Western Europe. By 1924, almost two million Jews had emigrated to the US alone, creating a large community in a nation relatively free of the persecutions of rising European anti-Semitism (see History of the Jews in the United States).

The Holocaust

Main article: The HolocaustThis anti-Semitism reached its most destructive form in the policies of Nazi Germany, which made the destruction of the Jews a priority, culminating in the killing of approximately six million Jews during the Holocaust from 1941 to 1945. Originally, the Nazis used death squads, the Einsatzgruppen, to conduct massive open-air killings of Jews in territory they conquered. By 1942, the Nazi leadership decided to implement the Final Solution, the genocide of all of the Jews of Europe, and increase the pace of the Holocaust by establishing extermination camps specifically to kill Jews. Millions of Jews who had been confined to diseased and massively overcrowded Ghettos were transported to these "Death-camps" where they were either gassed or shot. Many Jews tried to escape Europe before or during the Holocaust, but were unable to find refuge, giving new urgency to the Zionist goal of establishing a Jewish homeland.

Israel

Main article: IsraelIn 1948, the Jewish state of Israel was founded, creating the first Jewish nation since the Roman destruction of Jerusalem. After a series of wars with neighboring Arab countries, almost all of the 900,000 Jews previously living in North Africa and the Middle East fled to the Jewish state, joining an increasing number of immigrants from post-War Europe. By the end of the 20th century, Jewish population centers had shifted dramatically, with the United States and Israel being the centers of Jewish secular and religious life.

Persecution

Main article: Persecution of Jews- Related articles: Anti-Semitism, History of anti-Semitism, Modern anti-Semitism

Jewish leadership

Main article: Jewish leadershipThere is no single governing body for the Jewish community, nor a single authority with responsibility for religious doctrine. Instead, a variety of secular and religious institutions at the local, national, and international levels lead various parts of the Jewish community on a variety of issues.

Famous Jews

Main article: List of Jews Main article: List of Jews by countryJews have made contributions in a broad range of human endeavors, including the sciences, arts, politics, business, etc.

See also

A full guide to topics related to the Jews is available from the guide at the top of this page. Additional topics of interest include:

|

|

External links

General

|

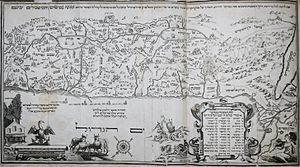

Maps

Photos

|

Major Jewish secular organizations

|

Global Jewish communities

|

|

Zionist institutions

|

Israeli institutions

|

Lists of notable Jews

|

|

Religious links

|

|

Notes

- Data based on a study by Jewish People Policy Institute (JPPI). See Jewish people near zero growth by Tovah Lazaroff, Jerusalem Post, June 24, 2004.

- See, for example Jews by country page for higher estimates.

- Data based on a study by the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. See (Updated to June 2005).

- 1993 Russian census. Some estimates are much higher, the US State Department Religious Freedom Report estimates the number of Jews in Russia alone at 600,000 to 1 million.

- Jewish Virtual Library, JewFAQ

- "airlifted tens of thousands of Ethiopian Jews". July 7.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - "NJPS: Intermarriage: Defining and Calculating Intermarriage". July 7.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - "World Jewish Congress Online". July 7.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - "The Virtual Jewish History Tour - Mexico". July 7.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help)