This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Dado~enwiki (talk | contribs) at 01:35, 28 January 2006 (→Srebrenica Genocide Denial and Revisionism Explained: Revised definition of Historical revisionism per its article). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:35, 28 January 2006 by Dado~enwiki (talk | contribs) (→Srebrenica Genocide Denial and Revisionism Explained: Revised definition of Historical revisionism per its article)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)The Srebrenica massacre was the July 1995 killing of an estimated 7,800 to 8,000 Bosniak males, ranging in age from teenagers to the elderly, in the region of Srebrenica by a Serb Army of Republika Srpska under general Ratko Mladić including Serbian state special forces "Scorpions". The same special forces commited war crimes in Kosovo in 1999. The Srebrenica massacre is considered one of the largest mass murders in Europe since World War II and one of the most horrific and controversial events in recent European history.

Mladić and other Serb army officers have since been indicted for various war crimes, including genocide, at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY). The ICTY's final ruling was that the massacre was indeed an act of genocide.

Background

The conflict in Eastern Bosnia

- See also History of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia began its journey to independence with a parliamentary declaration of sovereignty on October 15 1991. The Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was recognised by the European Community on April 6 1992 and by the United States the following day. International recognition did not end the matter, however, and a fierce struggle for territorial control ensued among the three major groups in Bosnia: Bosniak, Serb and Croat. The international community made various attempts to establish peace, but their success was very limited. In the Eastern part of Bosnia, close to Serbia, the conflict was particularly fierce between the Serbs and the Bosniaks.

Serbs intended to preserve Bosnia and Herzegovina as a component part of the former state. That was indeed their fundamental, long-term, and political objective in Bosnia and Herzegovina. They wanted to live in the same state with other Serbs, and the only state that could guarantee that was the former Yugoslavia. Serbs believed that the area of Central Podrinje (Srebrenica region) had a primary strategic importance for them. They thought that without the area of Central Podrinje, there would be no Republika Srpska, as there would be no territorial integrity of Serb ethnic territories. The Serbs would have to accept the Bosnian enclave within their ethnic territories. The territory would be split in two, the whole area would be disintegrated, and it would be separated from Serbia proper and from areas which are inhabited almost 100% by Serb population.

In spite of Srebrenica’s predominantly Bosniak population, Serb paramilitaries from the area and neighbouring parts of eastern Bosnia gained control of the town for several weeks early in 1992. In May 1992, however, a group of Bosnian fighters under the leadership of Naser Orić managed to recapture Srebrenica. Over the next several months, Orić and his men pressed outward in a series of raids. By September 1992, Bosnian forces from Srebrenica had linked up with those in Žepa, a Bosniak-held town to the south of Srebrenica. By January 1993, the enclave had been further expanded to include the Bosnian-held enclave of Cerska located to the west of Srebrenica. At this time the Srebrenica enclave reached its peak size of 900 square kilometres, although it was never linked to the main area of Bosnian-held land in the west and remained a vulnerable island amid Serb-controlled territory .

In January 1993, Bosnian forces attacked the Serb village of Kravica. Over the next few months, the Bosnian Serbs responded with a counter-offensive, eventually capturing the villages of Konjević Polje and Cerska, severing the link between Srebrenica and Žepa and reducing the size of the Srebrenica enclave to 150 square kilometres. Bosniak residents of the outlying areas converged on Srebrenica town and its population swelled to between 50,000 and 60,000 people. During this military activity in the months following January 1993, there were reports of terror inflicted by Bosniaks on Serb civilians and by Serbs on Bosniak civilians.

General Philippe Morillon of France, the Commander of the UN Protection Force (UNPROFOR) visited Srebrenica in March 1993. By then the town was overcrowded and siege conditions prevailed. There was almost no running water as the advancing Serb forces had destroyed the town’s water supplies. People relied on makeshift generators for electricity. Food, medicine and other essentials were extremely scarce. Before leaving, General Morillon told the panicked residents of Srebrenica at a public gathering that the town was under the protection of the UN and that he would never abandon them.

Between March and April 1993, approximately 8,000 to 9,000 Bosniaks were evacuated from Srebrenica under the auspices of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The evacuations were opposed by the Bosnian government in Sarajevo as contributing to the ethnic cleansing of the territory.

The Bosnian Serb authorities remained intent on capturing the enclave, which, because of its proximity to the Serbian border and because it was entirely surrounded by Serb-held territory, was both strategically important and vulnerable to capture. On April 13 1993, the Bosnian Serbs told the UNHCR representatives that they would attack the town within two days unless the Bosniaks surrendered and agreed to be evacuated.

April 1993: The Security Council Declares Srebrenica a “Safe Area”

On April 16 1993, the United Nations Security Council responded by passing resolution 819, declaring that "all parties and others concerned treat Srebrenica and its surroundings as a safe area which should be free from any armed attack or any other hostile act". The Security Council created two other UN protected enclaves at the same time: Žepa and Goražde. On April 18 1993, the first group of UNPROFOR troops arrived in Srebrenica.

Generally, the Bosnian Serb forces surrounding the enclave were considered well disciplined and well armed. The Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) was organised on a geographic basis and Srebrenica fell within the domain of the Drina Corps. Between 1,000 and 2,000 soldiers from three Drina Corps Brigades were deployed around the enclave. These Bosnian Serb forces were equipped with tanks, armoured vehicles, artillery and mortars. The unit of the Army of Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH) that remained in the enclave – the 28th Division - was neither well organised nor equipped. A firm command structure and communications system was lacking, some ARBiH soldiers carried old hunting rifles or no weapons at all and few had proper uniforms. However, the ICTY Trial Chamber also heard evidence that the 28th Division was not as weak as they have been portrayed in some quarters. Certainly the number of men in the 28th Division outnumbered those in the Drina Corps and reconnaissance and sabotage activities were carried out on a regular basis against the VRS forces in the area.

From the outset, both parties to the conflict violated the “safe area” agreement. The ICTY Trial Chamber heard evidence of a deliberate Serb strategy to limit access by international aid convoys into the enclave. Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Karremans (the Dutch Bat Commander) testified that his personnel were prevented from returning to the enclave by Serb forces and that equipment and ammunition were also prevented from getting in. Essentials, like food, medicine and fuel, became increasingly scarce. Some Bosniaks in Srebrenica complained of attacks by Serb soldiers. Insofar as the ARBiH is concerned, General Halilović testified that, immediately after signing the “safe area” agreement, he ordered members of the ARBiH in Srebrenica to pull all armed personnel and military equipment out of the newly established demilitarised zone. The ICTY Trial Chamber heard credible and largely uncontested evidence of a consistent refusal by the Bosniaks to abide by the agreement to demilitarise the “safe area”. Bosnian helicopters flew in violation of the no-fly zone; the ARBiH opened fire toward Serb lines and moved through the “safe area”; the 28th Division was continuously arming itself; and at least some humanitarian aid coming into the enclave was appropriated by the ARBiH. To the Serbs it appeared that Bosnian forces in Srebrenica were using the “safe area” as a convenient base from which to launch offensives against the VRS and that UNPROFOR was failing to take any action to prevent it. General Halilovic admitted that Bosnian helicopters had flown in violation of the no-fly zone and that he had personally dispatched eight helicopters with ammunition for the 28th Division. In moral terms, he did not see it as a violation of the “safe area” agreement given that the Bosniaks were so poorly armed to begin with.

Early 1995: The Situation in the Srebrenica “Safe Area” Deteriorates

By early 1995, fewer and fewer supply convoys were making it through to the enclave. The Dutch Bat soldiers who had arrived in January 1995 watched the situation deteriorate rapidly in the months after their arrival. The already meagre resources of the civilian population dwindled further and even the UN forces started running dangerously low on food, medicine, fuel and ammunition. Eventually, the peacekeepers had so little fuel that they were forced to start patrolling the enclave on foot. Dutch Bat soldiers who went out of the area on leave were not allowed to return and their number dropped from 600 to 400 men. In March and April, the Dutch soldiers noticed a build-up of Bosnian Serb forces near two of the observation posts, "OP Romeo" and "OP Quebec".

Spring 1995: The Serbs Plan To Attack the Srebrenica “Safe Area”

In March 1995, Radovan Karadžić, President of Republika Srpska (“RS”), in spite of the international community pressure to end the war and the ongoing efforts to negotiate a peace agreement, issued a directive to the VRS concerning the long-term strategy of the VRS forces in the enclave. The directive, known as “Directive 7”, specified that the VRS was to: "Complete the physical separation of Srebrenica from Žepa as soon as possible, preventing even communication between individuals in the two enclaves. By planned and well-thought out combat operations, create an unbearable situation of total insecurity with no hope of further survival or life for the inhabitants of Srebrenica."

Just as envisaged in this decree, by mid 1995, the humanitarian situation of the Bosniak civilians and military personnel in the enclave was catastrophic. In early July 1995, a series of reports issued by the 28th Division reflected the urgent pleas of the ARBiH forces in the enclave for the humanitarian corridor to be deblocked and, when this failed, the tragedy of civilians dying from starvation.

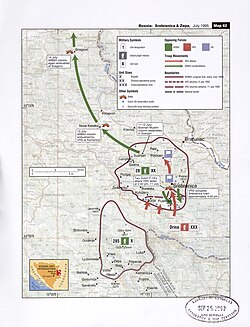

6-11 July 1995: The Take-Over of Srebrenica

Serbs violated the UN Safe Area in July 1995. By the evening of July 9, 1995, the VRS Drina Corps entered four kilometres deep into the enclave, halting just one kilometre short of Srebrenica town. Late on 9 July 1995, emboldened by this success and the lack of resistance from the Bosniaks as well as the absence of any significant reaction from the international community, President Karadžić issued a new order authorising the VRS Drina Corps to capture the town of Srebrenica.

On the morning of July 10 1995, the situation in Srebrenica town was tense. Residents, some armed, crowded the streets. Lieutenant-Colonel Karremans sent urgent requests for NATO air support to defend the town, but no assistance was forthcoming until around 1430 hours on July 11 1995, when NATO bombed VRS tanks advancing towards the town. NATO planes also attempted to bomb VRS artillery positions overlooking the town, but had to abort the operation due to poor visibility. NATO plans to continue the air strikes were abandoned following VRS threats to kill Dutch troops being held in the custody of the VRS, as well as threats to shell the UN Potočari compound on the outside of the town, and surrounding areas, where 20,000 to 30,000 civilians had fled.

The Massacre

The Crowd at Potočari

The UN forces did nothing to protect the Bosniak civilians in Srebrenica. Faced with the reality that Srebrenica had fallen under the control of Bosnian Serb forces, thousands of Bosniak residents from Srebrenica fled to the nearby hamlet of Potočari seeking protection within the UN compound. By the evening of July 11 1995, approximately 20,000 to 25,000 Bosniak refugees were gathered in Potočari. Several thousand had pressed inside the UN compound itself, while the rest were spread throughout the neighbouring factories and fields. Though the vast majority were women, children, elderly or disabled, 63 witnesses estimated that there were at least 300 men inside the perimeter of the UN compound and between 600 and 900 men in the crowd outside.

The Humanitarian Crisis in Potočari: 11-13 July 1995

Conditions in Potočari were deplorable. There was very little food or water available and the July heat was stifling. One of the Dutch Bat officers described the scene as follows: "They were panicked, they were scared, and they were pressing each other against the soldiers, my soldiers, the UN soldiers that tried to calm them. People that fell were trampled on. It was a chaotic situation."

12-13 July: Crimes Committed in Potočari

On 12 July 1995, as the day wore on, the already miserable physical conditions were compounded by an active campaign of terror, which increased the panic of the residents, making them frantic to leave. The refugees in the compound could see Serb soldiers setting houses and haystacks on fire. Throughout the afternoon of 12 July, Serb soldiers mingled in the crowd. One witness recalled hearing the soldiers cursing the Bosniaks and telling them to leave; that they would be slaughtered; that this was a Serb country. Killings occurred.

In the late morning of 12 July, a witness saw a pile of 20 to 30 bodies heaped up behind the Transport Building in Potočari, alongside a tractor-like machine. Another testified that, at around 12:00 hours on 12 July, he saw a soldier slay a child with a knife in the middle of a crowd of expellees. He also said that he saw Serb soldiers execute more than a hundred Bosniak men in the area behind the Zinc Factory and then load their bodies onto a truck, although the number and methodical nature of the murders attested to by this witness stand in contrast to other evidence on the Trial Record that indicates that the killings in Potočari were sporadic in nature.

As evening fell, the terror deepened. Screams, gunshots and other frightening noises were audible throughout the night and no one could sleep. Soldiers were picking people out of the crowd and taking them away: some returned; others did not. Witness recounted how three brothers – one merely a child and the others in their teens – were taken out in the night. When the boys’ mother went looking for them, she found them with their throats slit.

That night, a Dutch Bat medical orderly came across two Serb soldiers raping a young woman: "We saw two Serb soldiers, one of them was standing guard and the other one was lying on the girl, with his pants off. And we saw a girl lying on the ground, on some kind of mattress. There was blood on the mattress, even she was covered with blood. She had bruises on her legs. There was even blood coming down her legs. She was in total shock. She went totally crazy."

Throughout the night and early the next morning, stories about the rapes and killings spread through the crowd and the terror in the camp escalated.

The Separation of the Bosniak Men in Potočari

From the morning of 12 July, Serb forces began gathering men from the refugee population in Potočari and holding them in separate locations. Further, as the Bosniak refugees began boarding the buses, Serb soldiers systematically separated out men of military age who were trying to clamour aboard. Occasionally, younger and older men were stopped as well. These men were taken to a building in Potočari referred to as the “White House”. As the buses carrying the women, children and elderly headed north towards Bosnian-held territory, they were stopped along the way and again screened for men. As early as the evening of 12 July 1995, Major Franken of the Dutch Bat heard that no men were arriving with the women and children at their destination in Kladanj.

On 13 July 1995, the Dutch Bat troops witnessed definite signs that the Serbs were executing some of the Bosniak men who had been separated. For example, Corporal Vaasen saw two soldiers take a man behind the "White House". He then heard a shot and the two soldiers reappeared alone. Another Dutch Bat officer, saw Serb soldiers execute an unarmed man with a single gunshot to the head. He also heard gunshots 20-40 times an hour throughout the afternoon. When the Dutch Bat soldiers told Colonel Joseph Kingori, a United Nations Military Observer (UNMO) in the Srebrenica area, that men were being taken behind the "White House" and not coming back, Colonel Kingori went to investigate. He heard gunshots as he approached, but was stopped by Serb soldiers before he could find out what was going on.

The Column of Bosniak Men

As the situation in Potočari escalated towards crisis on the evening of 11 July 1995, word spread through the Bosniak community that the able-bodied men should take to the woods, form a column together with members of the 28th Division of the Army of Republic of Bosnian and Herzegovina and attempt a breakthrough towards Bosnian-held territory in the north. At around 2200 hours on the evening of 11 July 1995, the “division command”, together with the Bosniak municipal authorities of Srebrenica, made the decision to form the column. The young men were afraid they would be killed if they fell into Serb hands in Potočari and believed that they stood a better chance of surviving by trying to escape through the woods to Tuzla. The column gathered near the villages of Jaglici and Šušnjari and began to trek north. Witnesses estimated that there were between 10,000 and 15,000 men in the retreating column. Around one third of the men in the column were Bosnian soldiers from the 28th Division, although not all of the soldiers were armed.

At around midnight on 11 July 1995, the column started moving along the axis between Konjević Polje and Bratunac. On 12 July 1995, Serb forces launched an artillery fire on the column that was crossing an asphalt road between the area of Konjević Polje and Nova Kasaba on route to Tuzla. Only about one third of the men successfully made it across the asphalt road and the column was split in two parts. Heavy shooting and shelling continued against the remainder of the column throughout the day and during the night. Men from the rear of the column who survived this ordeal described it as a "man hunt".

The Bosniak men who had been separated from the women, children and elderly in Potočari numbering approximately 1,000, were transported to Bratunac and subsequently joined by Bosniak men captured from the column. Almost to a man, the thousands of Bosniak prisoners captured, following the take-over of Srebrenica, were executed. Some were killed individually or in small groups by the soldiers who captured them and some were killed in the places where they were temporarily detained. Most, however, were slaughtered in carefully orchestrated mass executions, commencing on 13 July 1995, in the region just north of Srebrenica.

The mass executions followed a well-established pattern. The men were first taken to empty schools or warehouses. After being detained there for some hours, they were loaded onto buses or trucks and taken to another site for execution. Usually, the execution fields were in isolated locations. The prisoners were unarmed and, in many cases, steps had been taken to minimise resistance, such as blindfolding them, binding their wrists behind their backs with ligatures or removing their shoes. Once at the killing fields, the men were taken off the trucks in small groups, lined up and shot. Those who survived the initial round of gunfire were individually shot with an extra round, though sometimes only after they had been left to suffer for a time.

A Plan to Execute the Bosniak of Srebrenica

A concerted effort was made to capture all Bosniak men of military age. In fact, those captured included many boys well below that age and elderly men several years above that age that remained in the enclave following the take-over of Srebrenica. These men and boys were targeted regardless of whether they chose to flee to Potočari or to join the Bosniak column.

Although Serbs have long been blamed for the massacre, it was not until June 2004 - following the Srebrenica commission's preliminary report - that Serb officials acknowledged that their security forces carried out the slaughter. A Serb commission's final report on the 1995 Srebrenica massacre acknowledged that the mass murder of more than 7,800 Bosniak men and boys was planned. The commission found that more than 7,800 were killed after it compiled 34 lists of victims.

The Mass Executions

The vast amount of planning and high-level coordination that had to be invested in killing thousands of men in a few days is apparent from even the briefest description of the scale and the methodical nature in which the executions were carried out.

The Morning of 13 July 1995: Jadar River Executions

A small-scale execution took place at Jadar River on 13 July 1995. The execution at Jadar River took place prior to midday, on 13 July 1995. 17 men were transported a short distance to a spot on the banks of the Jadar River. The men were then lined up and shot. One man, after being hit in the hip by a bullet, jumped into the river and managed to escape.

The Afternoon of 13 July 1995: Cerska Valley Executions

The first of the large-scale executions happened on the afternoon of 13 July 1995. Between 1,000 and 1,500 Bosniak men from the column fleeing through the woods, who had been captured and detained in Sandici Meadow, were bussed or marched to the Kravica Warehouse on the afternoon of 13 July 1995. At around 18.00 hours, when the warehouse was full, the soldiers started throwing grenades and shooting directly into the midst of the men packed inside. One survivor recalled: all of a sudden there was a lot of shooting in the warehouse, and we didn’t know where it was coming from. There were rifles, grenades, bursts of gunfire and it was – it got so dark in the warehouse that we couldn’t see anything. People started to scream, to shout, crying for help. And then there would be a lull, and then all of a sudden it would start again. And they kept shooting like that until nightfall in the warehouse. Guards surrounding the building killed prisoners who tried to escape through the windows. By the time the shooting stopped, the warehouse was filled with corpses.

Analyses of hair, blood and explosives residue, collected at the Kravica Warehouse, provide strong evidence of the killings. Experts determined the presence of bullet strikes, explosives residue, bullets and shell cases, as well as human blood, bones and tissue adhering to the walls and floors of the building. Forensic evidence presented by the ICTY Prosecutor suggests a link between the Krivaca Warehouse, the primary mass grave known as Glogova 2, and the secondary grave known as Zeleni Jadar 5.

13-14 July 1995: Tišca

As the buses crowded with Bosniak women, children and elderly made their way from Potočari to Kladanj, they were stopped at Tišca, searched, and the Bosniak men found on board were removed from the bus. The evidence reveals a well-organised operation in Tišca.

From the checkpoint, a witness was taken to a nearby school, where a number of other prisoners were being held. An officer directed the soldier escorting the witness towards a nearby school where many other prisoners were being held. At the school, a soldier on a field telephone appeared to be transmitting and receiving orders. Sometime around midnight, the witness was loaded onto a truck with 22 other men with their hands tied behind their backs. At one point the truck stopped and a soldier on the scene said : "Not here. Take them up there, where they took people before." The truck reached another stopping point and the soldiers came around to the back of the truck and started shooting the prisoners.

14 July 1995: Grbavci School Detention Site and Orahovac Execution site

A large group of the prisoners who had been held overnight in Bratunac were bussed in a convoy of 30 vehicles to the Grbavci school in Orahovac early in the morning of 14 July 1995. When they got there, the school gym was already half-filled with prisoners who had been arriving since the early morning hours and, within a few hours, the building was completely full. Survivors estimated that there were 2,000 to 2,500 men there, some of them very young and some quite elderly, although the ICTY Prosecution suggested this may have been an over-estimation and that the number of prisoners at this site was probably closer to 1,000. Some prisoners were taken outside and killed. At some point, a witness recalled, General Mladić arrived and told the men: "Well, your government does not want you, and I have to take care of you."

After being held in the gym for several hours, the men were led out in small groups to the execution fields that afternoon. Each prisoner was blindfolded and given a drink of water as he left the gym. The prisoners were then taken in trucks to the execution fields less than one kilometre away. The men were lined up and shot in the back; those who survived the initial gunfire were killed with an extra shot. Two adjacent meadows were used; once one was full of bodies, the executioners moved to the other. While the executions were in progress, the survivors said, earth-moving equipment was digging the graves. A witness who survived the shootings by pretending to be dead, reported that General Mladić drove up in a red car and watched some of the executions.

The forensic evidence supports crucial aspects of the survivors’ testimony. Aerial photos show that the ground in Orahovac was disturbed between 5 and 27 July 1995 and again between 7 and 27 September 1995. Two primary mass graves were uncovered in the area, and were named "Lazete-1" and "Lazete-2" by investigators. The "Lazete-1" gravesite was exhumed by the ICTY Prosecution between 13 July and 3 August 2000. All of the 130 individuals uncovered, for whom sex could be determined, were male. One hundred and thirty eight blindfolds were uncovered in the grave. Identification material for twenty-three individuals, listed as missing following the fall of Srebrenica, was located during the exhumations at this site. The gravesite "Lazete-2" was partly exhumed by a joint team from the OTP and Physicians for Human Rights between 19 August and 9 September 1996 and completed in 2000. All of the 243 victims associated with "Lazete-2" were male and the experts determined that the vast majority died of gunshot injuries. In addition, 147 blindfolds were located. One victim also had his legs bound with a cloth sack.

Forensic analysis of soil/pollen samples, blindfolds, ligatures, shell cases and aerial images of creation/disturbance dates, further revealed that bodies from the "Lazete-1" and "Lazete-2" graves were removed and reburied at secondary graves named Hodžići Road 3, 4 and 5. Aerial images show that these secondary gravesites were created between 7 September and 2 October 1995, and all of them were exhumed in 1998.

14 - 16 July 1995: Pilica School Detention Site and Branjevo Military Farm Execution Site

On 14 July 1995, more prisoners from Bratunac were bussed northward to a school in the village of Pilica, north of Zvornik. As at other detention facilities, there was no food or water and several men died in the school gym from heat and dehydration. The men were held at the Pilica School for two nights. On 16 July 1995, following a now familiar pattern, the men were called out of the school and loaded onto buses with their hands tied behind their backs. They were then driven to the Branjevo Military Farm, where groups of 10 were lined up and shot.

Mr. Dražen Erdemović was a member of the VRS 10th Sabotage Detachment (a Main Staff subordinate unit) and participated in the mass execution. Mr. Erdemović appeared as a Prosecution witness and testified: "The men in front of us were ordered to turn their backs. When those men turned their backs to us, we shot at them. We were given orders to shoot."

Mr. Erdemović said that all but one of the victims wore civilian clothes and that, except for one person who tried to escape, they offered no resistance before being shot. Sometimes the executioners were particularly cruel. When some of the soldiers recognised acquaintances from Srebrenica, they beat and humiliated them before killing them. Mr. Erdemovic had to persuade his fellow soldiers to stop using a machine gun for the killings; while it mortally wounded the prisoners it did not cause death immediately and prolonged their suffering.

Mr. Erdemović testified that, at around 15:00 hours on 16 July 1995, after he and his fellow soldiers from the 10th Sabotage Detachment had finished executing the prisoners at the Branjevo Military Farm, they were told that there was a group of 500 Bosniak prisoners from Srebrenica trying to break out of a nearby club. Mr. Erdemović and the other members of his unit refused to carry out any more killings. They were then told to attend a meeting with the Lieutenant Colonel at a café in Pilica. Mr. Erdemović and his fellow-soldiers travelled to the café as requested and, as they waited, they could hear shots and grenades being detonated. The sounds lasted for approximately 15-20 minutes after which a soldier from Bratunac entered the café to inform those present that "everything was over".

Between 1,000 and 1,200 men were killed in the course of that day at this execution site.

Aerial photographs, taken on 17 July 1995, of an area around the Branjevo Military Farm , show a large number of bodies lying in the field near the farm, as well as traces of the excavator that collected the bodies from the field.

The progress of finding victim bodies in the Srebrenica region, often in mass graves, exhuming them and finally identifying them was relatively slow. By 2002, 5,000 bodies were exhumed but only 200 were identified. However, since then the exhumed body count has risen to 6,000 and the identification has been completed for over 2,000, as of 2005.

The Reburials

The forensic evidence presented to the Trial Chamber of ICTY suggests that, commencing in the early autumn of 1995, the Serbs engaged in a concerted effort to conceal the mass killings by relocating the primary graves to remote secondary gravesites. All of the primary and secondary mass gravesites associated with the take-over of Srebrenica located by the OTP were within the Drina Corps area of responsibility.

Most significantly, the forensic evidence also demonstrates that, during a period of several weeks in September and early October 1995, Serb forces dug up many of the primary mass gravesites and reburied the bodies in still more remote locations. Forensic tests have linked certain primary gravesites and certain secondary gravesites, namely: Branjevo Military Farm and Cancari Road 12; Petkovći Dam and Liplje 2; Orahovac (Lazete 2) and Hodžići Road 5; Orahovac (Lazete 1) and Hodžići Road 3 and 4; Glogova and Zeleni Jadar 5; and Kozluk and Cancari Road 3. The reburial evidence demonstrates a concerted campaign to conceal the bodies of the men in these primary gravesites, which was undoubtedly prompted by increasing international scrutiny of the events following the take-over of Srebrenica. Such extreme measures would not have been necessary had the majority of the bodies in these primary graves been combat victims.

Recent developments

Ratko Mladić and the political leader of Bosnian Serbs Radovan Karadžić have both been indicted for genocide, crimes against humanity and violations of the laws or customs of war at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. In 2001, Radislav Krstić, a Serb commander who had led the assault on Srebrenica alongside Mladić, was convicted by the tribunal on genocide charges and received 46 years to life in prison.

After a long-running discussion about the event in the Netherlands, the Dutch second cabinet of Wim Kok chose to resign in April 2002 after the official inquiry and report by the Nederlands Instituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie.

The Enclave, a three-part series based on the Srebrenica incident, was released in 1995 by the Dutch Public Broadcasting station. It has since been condensed into one movie and is regularly shown on US free satellite channel LinkTV.

In 2004, the international community's High Representative Paddy Ashdown had the Government of Republika Srpska form a committee to investigate the events. The committee released a report in October 2004 with 8,731 confirmed names of missing and dead persons from Srebrenica: 7,793 between 10th and 19th of July 1995 and further 938 people afterwards.

Findings of the committee remain generally disputed by the Serb nationalists, as they claim it was heavily pressured by the high representative. Nevertheless, Dragan Čavić, the president of Republika Srpska, acknowledged in a televised address that Serb forces killed several thousand civilians in violation of the international law, and asserted that Srebrenica was a dark chapter in Serb history. In his statement he used the word 'massacre' instead of 'genocide'.

On November 10 2004, the government of Republika Srpska issued an official apology. The statement came after government review of the Srebrenica committee's report. "The report makes it clear that enormous crimes were committed in the area of Srebrenica in July 1995," the Bosnian Serb government said .

As of 2004, the mass graves are still being dug up and the victims honorably laid to rest, providing a sense of closure for many families who lost their loved ones.

On January 18, 2005 two former Bosnian Serb officers, Vidoje Blagojević and Dragan Jokić, were convicted and imprisoned for their complicity in the Srebrenica massacre.

On June 2, 2005 video evidence emerged. It was introduced at the Milošević trial to testify the involvement of members of police units from Serbia in Srebrenica Massacre The video footage starts about 2hr 35 min. into the proceedings. The footage shows an orthodox priest blessing several soldiers. Later these soldiers are shown with tied up captives, dressed in civilian clothing and visibly physically abused. They were later identified as four minors as young as 16 and two men in their early twenties. The footage then shows the execution of four of the civilians and shows them lying dead in the field. At this point the cameraman expresses disappointment that the camera's battery is almost out. The soldiers then ordered the two remaining captives to take the four dead bodies into a nearby barn, where they were also killed upon completing this task.

The video has caused a public outrage in Serbia. In the days following its showing, the Serbian government quickly arrested some of the former soldiers identified on the video. The event has most extensively been covered by the newspaper Danas and radio and television station B92. As was reported by Bosnian media, at least one mother of a filmed captive saw the execution of her son on television. She claimed she was already aware of her son's death, and said she had been told that his body was burned following the execution. His remains were among those buried in Potočari in 2003.

On October 4, 2005, the Special Bosnian Serb Government Working Group said that 25,083 people were involved in the massacre including 19,473 members of various Bosnian Serb armed forces that actively gave orders or directly took part in the massacre. They have identified 17,074 by name.

US resolution 199

On June 27 2005, the United States House of Representatives passed a resolution (H. Res. 199 sponsored by Congressman Christopher Smith and Congressman Benjamin Cardin) commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide. The resolution was passed with overwhelming majority of 370 - YES votes, 1 - NO vote, and 62 - ABSENT .

The resolution is a bipartisan measure commemorating July 11, 1995-2005, the tenth anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre in which almost 8,000 men and boys were meticulously and methodically separated from their daughters, mothers, sisters and wives and then killed by Serb forces, buried in mass graves and then re-interred in secondary graves to cover up the crimes. Srebrenica fell to invading Serb forces on July 11, 1995 which at the time had been declared a UN "safe area" under the protection of the international community. The Srebrenica massacre was the worst genocidal atrocity in Europe since World War II.

The resolution states that "the policies of aggression and ethnic cleansing as implemented by Serb forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1992 and 1995 with the direct support of Serbian regime of Slobodan Milošević and its followers ultimately led to the displacement of more than 2,000,000 people, an estimated 200,000 killed, tens of thousands raped or otherwise tortured and abused, and the innocent civilians of Sarajevo and other urban centers repeatedly subjected to shelling and sniper attacks; meet the terms defining the crime of genocide in Article 2 of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, created in Paris on December 9, 1948, and entered into force on January 12, 1951."

Denial of the massacre, revisionism and scepticism

The Bosnian Serb side has, under the pressure of the authority of Governor Ashdown, officially admitted the number of killed Muslims and expressed regrets for the massacre in 2004 (Comm. Inv. Ev. Srebrenica, 2004). Still the number of killed is presently disputed by some. All nations and international organizations involved consider it to have been a massacre, and most consider it to be a case of genocide. The government of the Republika Srpska entity has officially condemned the atrocity. While Serbia, officially, has condemned the massacre from the very beginning, some Serbs from Serbia had reservations about the number of people killed for some time. In the West, the radicals on both sides of the political spectrum have disputed the original accounts of the massacre for different reasons. Some radical liberals view the Srebrenica massacre as being another case of government propaganda in an unnecessary war. Their conservative counterparts consider the truth to have been manipulated by radical Islamists and their allies. Still, such views are not widely held in NATO countries other than Greece and France to a degree.

Still, many Serb groups espouse denial of massacre, claiming that the intentional mass murder of nearly 8,000 Bosniaks is grossly exaggerated and that Republika Srpska government had no extermination policy. Some others, who don't deny mass killings by the Republika Srpska have engaged in pointing out "immoral equivalencies" (e.g. the killing of Serbs by Naser Orić, the ethnic cleansing of Serbs in Croatia) and/or justifications for the executions (e.g. retaliation or punishment for sabotage, terrorism, or subversion).

Many Serbs distrusted the western explanation of the events due to the long delays in proving that there were mass graves in the area, and that people in them were indeed Bosniaks (it took almost a decade for a notable percentage of bodies to be identified). In their eyes, further doubt was cast at the mainstream story when the UN high representative Paddy Ashdown relieved and replaced the examining commission of Republika Srpska which reported that the initial (?) explanation was correct. This only exacerbated the concern that there was bias among the westerners resulting in focusing on the wartime acts of Serbs and neglecting those of Bosniaks and Croats.

The claims were made that Serb-inhabited villages and hamlets had been attacked by raids from Srebrenica between May 1992 and February 1993. Oric is presently awaiting trial at the ICTY on charges including his torturing of Serb prisoners of war and commanding Bosnian troops which killed Serbian soldiers and civilians in the surrounding villages. Recently two of the six charges by ICTY against Oric have been rejected. It is accepted by all sides that some of these acts happened and that there is a number of Serb people from those villages who are still unaccounted for. The Serbian government submitted a report to the United Nations in May 1994 explaining two dozen incidents of ethnic cleansing in the region of Srebrenica, Bratunac and Skelani, naming 301 Serbian civilians killed by Oric's troops. Recently, a list surfaced of 3,287 names of Serbs (it is unclear whether they were civilians or soldiers), which were allegedly killed in Srebrenica region and also in other regions of Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, the exact number of victims of the raids by Oric's forces is unknown (the Serbian government's list of 301 people is from 1994), and their bodies have not yet been found in mass graves. On the other hand, Bosniak bodies continue to be excavated, identified and buried.

Srebrenica Genocide Denial and Revisionism Explained

Srebrenica Genocide denial, also called Srebrenica Genocide revisionism, is the belief that the Srebrenica genocide did not occur, or, more specifically: that far fewer than around 8,000 Bosniaks were killed by the Bosnian Serb Army (numbers below 5,000, most often around 2,000 are typically cited); that there never was a centrally-planned Bosnian Serb Army's attempt to exterminate the Bosniaks of Srebrenica; and/or that there were not mass killings at the extermination sites. Those who hold this position often further claim that Bosniaks and/or Western media know that the Srebrenica genocide never occurred, yet that they are engaged in a massive conspiracy to maintain the illusion of a Srebrenica genocide to further their political agenda. These views are not accepted as credible by objective historians.

Srebrenica genocide deniers almost always prefer to be called Srebrenica genocide revisionists. Most scholars contend that the latter term is misleading. Historical revisionism is a well-accepted part of the study of history; it is the reexamination of historical facts, with an eye towards updating histories with newly discovered, more accurate, or less biased information. The implication is that history as it has been traditionally told may not be entirely accurate. The term historical revisionism has a second meaning, the illegitimate manipulation of history for political purposes. For example, Srebrenica genocide deniers typically willfully misuse or ignore historical records in order to attempt to prove their conclusions.

Notes

- "By seeking to eliminate a part of the Bosnian Muslims, the Bosnian Serb forces committed genocide. The Appeals Chamber states unequivocally that the law condemns, in appropriate terms, the deep and lasting injury inflicted, and calls the massacre at Srebrenica by its proper name: genocide." (ICTY 2004, para. 37)

References

- The Commission for the Investigation of the Events in and around Srebrenica between 10 and 19 July 1995, published 2004. The Events in and around Srebrenica between 10 and 19 July 1995, available from Domovina net.

- ICTY, 2004. Appeals chambers judgement in Prosecuter v. Radislav Krstić, available from ICTY website.

- NIOD, 2002. Srebrenica, een 'veilig' gebied. Boom, Amsterdam. ISBN 9053527168. English translation available at the NIOD Srebrenica website.

- David Rohde. 1997. Endgame: The Betrayal and Fall of Srebrenica, Europe's Worst massacre Since World War II. WestviewPress. ISBN 0813335337.

- Van Gennep, 1999. Srebrenica: Het Verhaal van de Overlevenden . Van Gennep, Amsterdam. ISBN 90-5515-224-2. (translation of: Samrtno Srebrenicko Ijeto '95, Udruzenje gradana 'Zene Srebrenice', Tuzla, 1998).

- US resolution 199, 2005.

See also

External links

- Initial indictment at the ICTY against Karadžić and Mladić for Srebrenica.

- The Association Women of Srebrenica.

- The uncensored version of the Bosnian execution video Warning: shocking content!

- Preliminary list of 8106 Bosniaks killed in Srebrenica.

- Blog regarding Srebrenica Genocide

- U.S. Resolution 199

- Panel and commemorative event held at Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York by the Academy of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Carnegie Council

- Municipality of Srebrenica - Official Web Site