This is an old revision of this page, as edited by GregorB (talk | contribs) at 14:38, 20 October 2010 (Typo). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 14:38, 20 October 2010 by GregorB (talk | contribs) (Typo)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Croatian War of Independence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Yugoslav Wars | |||||||||

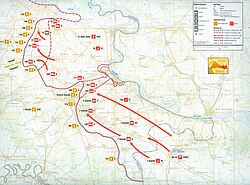

| File:627px-Map of events during the Croatian War of Independence 1991-1992.jpg Map of events during the Croatian War of Independence 1991-1992 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

1991:

(Serbian and Montenegrin units involved up to May 1992) |

1991: | ||||||||

|

1992–1994: |

1992–1994: | ||||||||

|

1995: (limited involvement) |

1995: Bosnia and Herzegovina (Operation Storm, 1995) | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

(Commander, 5th Corps ARBiH 1995) | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Serbian sources:

International sources:

|

Croatian sources:

or

or

| ||||||||

| About 10,000 or about 20,000 killed on both sides | |||||||||

|

a The Serb-controlled units of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) continued to fight throughout 1991 and a part of 1992 in support of the Republic of Serbian Krajina, but no longer as an officially separate combatant authority. b The Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was significant for the conflict only in 1995. In 1995, after the Washington Agreement, the state was de facto representative of the Bosnian Croat and Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) ethnic groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina itself. Not to be confused with Bosnia and Herzegovina, which encompasses all three Bosnian ethnic groups. | |||||||||

| Yugoslav Wars | |

|---|---|

The Croatian War of Independence was a war fought in Croatia from 1991 to 1995. It was fought between the Croatian government, having declared independence from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and both the Serbia-controlled Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and local Serb forces, who established the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) within Croatia.

Initially, the war was waged between Croatian police forces and Serbs living in the Yugoslav Republic of Croatia. As the JNA came under increasing Serbian influence in Belgrade, many of its units began assisting the Serbs fighting in Croatia. The Croatian side aimed to establish a sovereign country outside Yugoslavia, and the Serbs, supported from Serbia, opposed the secession and wanted to remain a part of Yugoslavia, effectively seeking new boundaries in Croatia with a Serb majority or significant minority or by conquering as much of Croatia as possible. The goal was primarily to remain in the same state with the rest of the Serbian nation, which was interpreted as an attempt to form a "Greater Serbia" by Croats (and Bosniaks). The ICTY also interpreted it as an attempt to create a unified Serb state. In the verdict against Milan Martić, the ICTY stated the following:

Between 1991 and 1995, Martić held positions of Minister of Interior, Minister of Defence and President of the self-proclaimed "Serbian Autonomous Region of Krajina" (SAO Krajina), which was later renamed "Republic of Serbian Krajina"(RSK). He was found to have participated during this period in a joint criminal enterprise which included Slobodan Milošević, whose aim was to create a unified Serbian state through commission of a widespread and systematic campaign of crimes against non-Serbs inhabiting areas in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina envisaged to become parts of such a state.

At the beginning of the war, the JNA tried to forcefully keep Croatia in Yugoslavia by occupying the whole of Croatia.

In Croatia, the war is referred to as the Homeland War (Croatian: Domovinski rat) or Greater-Serbian aggression (Croatian: Velikosrpska agresija). In the Serbian language, the phrase War in Croatia (Serbian: Rat u Hrvatskoj) is the most common name.

Background: 1980s

Main article: Timeline of Yugoslavian breakupThe war in Croatia resulted from the rise of nationalism in the 1980s which slowly led to the dissolution of Yugoslavia. A crisis emerged in Yugoslavia with the weakening of the Communist states in Eastern Europe towards the end of the Cold War, as symbolised by the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. In Yugoslavia, the national communist party, officially called Alliance or the League of Communists had lost its ideological potency.

In the 1980s, Albanian secessionist movements in the Autonomous Province of Kosovo, Republic of Serbia, led to the repression of the Albanian majority in Serbia's southern province. The more prosperous republics of Slovenia and Croatia wanted to move towards decentralisation and democracy. Serbia, headed by Slobodan Milošević, adhered to centralism and one party rule through the Yugoslav Communist Party. Milošević effectively ended the autonomy of the Kosovo and Vojvodina autonomous regions.

As Slovenia and Croatia began to seek greater autonomy within the Federation, including confederate status and even full independence, the nationalist ideas started to grow within the ranks of the still-ruling League of Communists. As Slobodan Milošević rose to power in Serbia, his speeches favoured the continuation of a single Yugoslav state, but one in which all power would be centralized and devolved to Belgrade.

An important factor in Croatia's preservation of its pre-war borders was the Yugoslav Constitution change in 1974 which allowed all republics inside Yugoslavia to become independent through elections. These borders were agreed on all sides during AVNOJ in 1945.

The Serbian Radical Party (SRS) president Vojislav Šešelj visited the US in 1989 and was later awarded the honorary title of ‘Vojvoda’ (duke) by Momčilo Đujić, a WWII Chetnik leader, during a commemoration of the Battle of Kosovo. This caused an outrage across Yugoslavia. Years later, Milan Babić (Croatian Serb leader) testified that Momčilo Đujić had financially supported the Serbs in SR Croatia in the 1990s.

Future leader of Croatia Franjo Tuđman made international visits during the late 1980s in order to garner support from the Croatian diaspora for the Croatian national cause.

In March 1989, the crisis in Yugoslavia deepened after the adoption of amendments to the Serbian constitution. This allowed the Serbian republic's government to re-assert effective power over the autonomous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina. Before this point, a number of political decisions were legislated from within these provinces. They also had a vote on the Yugoslav federal presidency level (six members from the republics and two members from the autonomous provinces). Serbia, under president Slobodan Milošević, gained control over three out of eight votes in the Yugoslav presidency and this was used in 1991 when the Serbian parliament changed Riza Sapunxhiu and Nenad Bućin, representatives of Kosovo and Vojvodina, with Jugoslav Kostić and Sejdo Bajramović.

The last vote was given by Montenegro whose government survived a first putsch in October 1988 but not second in January 1989. Serbia was thus with 4 out of 8 presidency votes able to heavily influence the decisions of the federal government. This situation led to objections in other republics (Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia) and calls for reform of the Yugoslav Federation.

1990: Electoral and constitutional moves

The weakening of the communist regime allowed nationalism to spread its political presence, even within the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (CY). In January 1990, the League of Communists broke up on the lines of the individual republics. At the 14th Extraordinary Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, on 20 January 1990, the delegations of the republics could not agree on the main issues in the Yugoslav federation. The Croatian delegation demanded a looser federation, while the Serbian delegation, headed by Milošević, opposed this. As a result, the Slovenian and Croatian delegates left the Congress.

The first free elections were then scheduled a few months later in Croatia and Slovenia. The elections in Croatia were held in April/May, the first round on 22 April, and the second round on 6 May.

In 1989 a number of political parties had been founded, among them the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ - Hrvatska Demokratska Zajednica), led by Croatian nationalist Franjo Tuđman. The HDZ based its campaign on an aspiration for greater sovereignty of Croatia and on a general anti-Yugounitarist ideology, fueling the sentiment of Croats that "only the HDZ could protect Croatia from the aspirations of Serbian elements led by Slobodan Milošević towards a Greater Serbia". It topped the poll in the elections (followed by Ivica Račan's reformed communists, Social Democratic Party of Croatia) and formed a new Croatian Government.

On 13 May 1990, a football game was held in Zagreb between Zagreb's Dinamo team and Belgrade's Crvena Zvezda team. The game erupted into violence, between groups of supporters and the police.

On 30 May 1990, the new Croatian Parliament held its first session, and President Tuđman announced his manifesto for a new Constitution (ratified at year-end - see below) and a multitude of political, economic and social changes, notably to what extent minority rights (mainly for Serbs), would be guaranteed. Local Serb politicians opposed the new constitution, on the grounds that the local Serb population would be threatened. Their prime concern was that a new constitution would not any more designate Croatia a "national state of the Croatian people, a state of the Serbian people and any other people living in it" but a "national state of the Croatian people and any people living in it".

In August 1990, an unrecognized mono-ethnic referendum was held in regions with a substantial Serb population (which would later become known as the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK)) (bordering western Bosnia and Herzegovina) on the question of Serb "sovereignty and autonomy" in Croatia. This was to counter the changes in the constitution. The Croatian government tried to block the referendum by sending police forces to police stations in Serb-populated areas to seize their weapons. Among other incidents, local Serbs from the southern hinterlands of Croatia, mostly around the city of Knin, blocked the roads to the tourist destinations in Dalmatia. This incident is known as the "Log revolution". Years later, during Milan Martić's trial, Milan Babić would claim that he was tricked by Martić into agreeing to the Log Revolution, and that it and the entire war in Croatia was Martić's responsibility, orchestrated by Belgrade. The Croatian government responded to the blockade of roads by sending special police teams in helicopters to the scene, but they were intercepted by JNA fighter jets and forced to turn back to Zagreb. The Serbs, who accuse the Croatian authorities of discrimination, felled pine trees or used bulldozers to block roads, sealing off towns like Knin and Benkovac near the Adriatic coast. On August 18, 1990, the Serbian newspaper Vecernje Novosti said almost "two million Serbs were ready to go to Croatia to fight".

The Serbs within Croatia did not initially seek independence before 1990. On 25 July 1990, a Serbian Assembly was established in Srb, north of Knin, as the political representation of the Serbian people in Croatia. The Serbian Assembly declared "sovereignty and autonomy of the Serb people in Croatia". On 21 December 1990, the SAO Krajina was proclaimed by the municipalities of the regions of Northern Dalmatia and Lika, in south-western Croatia. Article 1 of the Statute of the SAO Krajina defined the SAO Krajina as “a form of territorial autonomy within the Republic of Croatia” on which the Constitution of the Republic of Croatia, state laws and the Statute of the SAO Krajina were applied.

Following Tuđman's election and the perception of a threat from the new constitution, Serb nationalists in the Kninska Krajina region began taking armed action against Croatian government officials. Many were forcibly expelled or excluded from the RSK. Croatian government property throughout the region was increasingly controlled by local Serb municipalities or the newly established "Serbian National Council". This would later become the government of the breakaway Republic of Serbian Krajina.

On 22 December 1990, the Parliament of Croatia ratified the new constitution, changing the status of Serbs in Croatia to a 'national minority' from a 'constituent nation'. The percentage of those declaring themselves as Serbs, according to the 1991 census, was 12% (78% of the population declared itself to be Croat). This was read as taking away some of the rights from the Serbs granted by the previous Socialist constitution, thereby fueling extremism among the Serbs of Croatia. However, the constitution defined Croatia as “the national state of the Croatian nation and a state of members of other nations and minorities who are its citizens: Serbs who are guaranteed equality with citizens of Croatian nationality ”.

Immediately after the Slovenian referendum on independence and the new Croat constitution, the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) announced that a new defense doctrine would apply across the country. The Tito-era doctrine of "General People's Defense", in which each republic maintained a Territorial defense force (Teritorijalna obrana or TO), would henceforth be replaced by a centrally-directed system of defense. The republics would lose their role in defense matters and their TOs would be disarmed and subordinated to JNA headquarters in Belgrade.

1991: Military forces

The Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) was initially formed during World War II to carry out guerrilla warfare against Axis occupation. The success of the Partisan movement led to the JNA basing much of its operational strategy on guerrilla warfare. Due to the unique political stance of Yugoslavia in Europe, the strategic planners of the Army expected to face an attack by either NATO or Warsaw Pact forces. Expecting to be badly outmatched, the JNA decided to pursue a guerrilla strategy, which would prove disastrous in the upcoming war, since the JNA found itself in a position of an attacker without local civilian support - the very role they intended for invaders of Yugoslavia.

Still, on paper, the JNA looked like a powerful force with 2,000 tanks and 300 jet aircraft (all either Soviet or locally produced). However, by 1991, majority of this equipment was over 30 years old: it consisted substantialy out of T-54/55 tank and the MiG-21 aircraft. By contrast, more modern cheap anti-tank (like AT-5) and anti-aircraft (like SA-14) missiles were abundant and were designed to destroy much more advanced weaponry. With the retreat of the JNA forces in 1992, JNA units were reorganized as the Army of Serb Krajina, which was a direct heir to JNA organization with little improvement. During 1991, an important role in the Yugo/Serb military assault forces was filled by paramilitary units like Beli Orlovi, Srpski Četnički Pokret, etc. that committed numerous massacres against Croat and other non-Serbs civilians.

By contrast to this force, the Croatian Army was in much worse state. At the early stages of the war, lack of military units meant that the Croatian police force would take much of the brunt of fighting - eventually the police would form the core of the new military force - initially named "Zbor Narodne Garde" (ZNG), later "Hrvatska Vojska" (HV) - that was formed on 11 April 1991, but not really developed until 1993. Weaponry was always lacking and many units were formed either unarmed or with WW2-era rifles. The Croatian Army had just a handful of tanks (even older WW2 veterans like the T-34) and its air-force was even worse: a few old Antonov An-2 biplane crop-dusters were converted to drop makeshift bombs. However, since the soldiers were defending their homeland the army was exceptionally motivated, and was formed into local fighting units - so people from a village would defend their own village - which meant they were fairly effective in their home grounds. In August 1991, the Croat Army had fewer than 20 brigades, which would grow to 60 by the end of the year through general mobilization which was initiated in October. Seizing of JNA's barracks in the Battle of the barracks would slightly alleviate the problem of equipment shortage. Local volunteers and organizations like HOS were formed early on to ease the problem of lack of units, but were later integrated into the regular army.

By 1995, the Croatian Army would develop into an effective fighting force centered on the elite "Guard Brigades" (eight) and less effective "Home Defence Regiments" and regular brigades (most of which were reorganized into Regiments in 1992). This organization meant that in later campaigns, the Croatian army would pursue a variant of blitzkrieg tactics, with Guard brigades taking the role of punching holes in the enemy lines, while other units simply held the front at other points and completed the encirclement of enemy units.

1991: Preparations, followed by war

Mirko Kovač on the 10th anniversary of the end of the Croatian War of Independence"Croats became refugees in their own country."

Ethnic hatred grew and various incidents fueled the propaganda machines on both sides, thereby causing even more hatred. The conflict soon escalated into armed incidents in the majority-Serb populated areas. Serbs began a series of attacks on Croatian police units, killing more than 20 by the end of April. The Plitvice Lakes incident in late March 1991 stands out, with Josip Jović from Aržano being the first police officer killed by Serb forces.

In April 1991, the Serbs within the Republic of Croatia began to make serious moves to secede from that territory, that in turn seceded from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. It is a matter of debate to what extent this move was locally motivated and to what degree the Milošević-led Serb government gave the push to self-declare. In any event, the Republic of Serbian Krajina was declared consisting of Croatian territory with a substantial Serb population — which the Croatian government saw as a rebellion.

The Croatian Ministry of the Interior consequently started arming an increasing amount of special police forces, and this led to the building of a real army. On 9 April 1991, Croatian President Franjo Tuđman ordered the special police forces to be renamed Zbor Narodne Garde ("National Guard"), marking the creation of a separate military of Croatia.

Meanwhile, the federal army, the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and the local Territorial Defense Forces(Mainly Montenegrin) remained led by the nominally Federal government under Milošević. On occasion, the JNA sided with the local Croat Serb forces.

In May, Stipe Mesić, a Croat, was scheduled to be the chairman of the rotating presidency in Yugoslavia, but Serbia upped the ante by blocking the installation of him, so this maneuver technically left Yugoslavia without a leader.

On 19 May 1991, the Croatian authorities held a referendum on independence with the option of remaining in Yugoslavia as a looser union. Serb local authorities issued calls for a boycott, which were largely followed by Croatian Serbs, so the referendum was passed with 94.17% in favor. Croatia declared independence and "razdruženje" (departnerising) from Yugoslavia on 25 June 1991, but the European Commission urged them to place a three-month moratorium on the decision. Croatia thereby agreed to freeze its independence declaration for three months, helping to ease tension a little.

One month after the declaration of independence, Greater Serb forces held about a quarter of the country, mostly parts with a predominantly ethnic Serb population. They had obvious superiority in weaponry and equipment. The military strategy of the Greater Serbian forces partly consisted of extensive shelling, at times irrespective of civilians. As the war progressed, the cities of Dubrovnik, Gospić, Šibenik, Zadar, Karlovac, Sisak, Slavonski Brod, Osijek, Vinkovci and Vukovar all came under attack by the Yugoslav forces. The UN imposed a weapons embargo, which didn't affect JNA-backed Serb forces, but caused serious trouble for the newly-formed Croatian army. This led the Croatian government to start smuggling weapons over its borders.

In June/July 1991, the short armed conflict in Slovenia came to a speedy and fairly peaceful conclusion, partly because of the ethnic homogeneity of the Slovene population. During the war in Slovenia, a great number of Croatian and Slovenian soldiers refused to fight and deserted from the JNA. In July, in an attempt to salvage what remained of Yugoslavia, the JNA forces found themselves involved in operations against predominantly Croat areas - such as the Dalmatian coastal areas in the Battle of Dalmatia. Full-scale war erupted in August. As in Slovenia, where Croatian soldiers had refused to take part in the fight, with the start of military operations in Croatia, Croats started to desert the JNA en masse (especially since some kind of ceasefire was agreed at the end of War in Slovenia, and the alert level was lowered). Albanians and Macedonians started to search for a way to legally leave the JNA. In 1981, 60 % of the Yugoslav Army Non-commissioned officers and officer corps were Serbs, overrepresented by a ratio of 1.51. Despite efforts to homogenize the military ethnically, the JNA officer corps was dominated by Serbs and Montenegrins. Serbs and Montenegrins collectively reflected 38.8 per cent of the Yugoslav population, but made up 70 per cent of the JNA officer corps by 1990.

In August 1991, the border city of Vukovar came under siege and the Battle of Vukovar began. Serbian troops eventually completely surrounded the city. The Croat population of Vukovar, Croatian troops including the 204th Vukovar Brigade, entrenched themselves within Vukovar and held their ground against JNA elite Armoured and Mechanized brigades, as well as Serb paramilitary units. A certain number of ethnic Croatian civilians had taken shelter inside the city. Other elements of the civilian population fled the areas of armed conflict en masse. Death toll estimates for Vukovar, resulting from the siege, range from 1.798 up to 5.000.

There is evidence of extreme hardship imposed on the population at the time. Some estimates include 220,000 Croats and 300,000 Serbs internally displaced for the duration of the war in Croatia. However, at the peak of fighting in late 1991, around 550,000 people temporarily became refugees on the Croatian side. The 1991 census data and the 1993 RSK data for the territory of Krajina differ by some 102,000 Serbs and 135,000 Croats. In many places, large numbers of civilians were forced out by the military. This was labelled ethnic cleansing, a term whose meaning at the time ranged from eviction to murder. It was at this time that the term "ethnic cleansing" first entered the English lexicon.

On 3 October the Yugoslav Navy began a blockade of the main ports of Croatia. President Tuđman made a speech on 5 October 1991 in which he called upon the whole population to mobilize and defend against Greater-Serbian imperialism pursued by the Serb-led JNA, Serbian paramilitary formations and rebel Serb forces. On 7 October, an explosion occurred within the main government building in Zagreb while Tuđman, Mesić and Marković were present. The explosion destroyed several rooms of Banski dvori, but failed to kill any of the leaders. The government claimed that it was caused by a JNA air raid. Apparently, the Croatian army received information from Bihać (Bosnia and Herzegovina) JNA airfield the day before, about a top secret air mission being prepared for the next day, but these were not taken seriously due to lack of details. The JNA denied the responsibility and in turn claimed that the explosion was set up by the Croatian government itself. The next day, the Croatian Parliament cut off all remaining ties with Yugoslavia. 8 October is now Croatia's "Independence Day". The bombing of the government and the Siege of Dubrovnik that started in October were contributing factors to EU sanctions against Serbia. However, the international media's focus on (and exaggeration of) damage to Dubrovnik's artistic patrimony pushed concern with civilian casualties, and pivotal battles such as Vukovar, out of public view.

The situation for Croats in Vukovar over October and early November became ever more desperate. Towards the end of the battle, an increasing number of Croat civilians in hospitals and shelters marked with a red cross were hit by Serb forces. In 2007, two former Yugoslav army officers were sentenced for the Vukovar massacre at the International War Crimes Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia ICTY in The Hague. Veselin Šljivančanin was sentenced to 17 years and Mile Mrkšić to 20 years in prison. Prosecutors say that after the capture of Vukovar, the Yugoslav Army (JNA) handed over several hundred Croats to rebel Serbian forces. Of these, at least 264 (including injured soldiers, women, children and the elderly) were murdered and buried in mass graves in the neighbourhood of Ovcara on the outskirts of Vukovar. The city's mayor Slavko Dokmanović was also brought to trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, but committed suicide in 1998 in captivity before proceedings began.

On 18 November 1991, Vukovar fell to the Serbs after a three-month siege and the Vukovar massacre took place, while the survivors were transported to prison camps, the majority ending up in Sremska Mitrovica prison camp. The town of Vukovar was almost completely destroyed. The sustained focus on a siege facilitated the attraction of heavy international media attention. Many international journalists were present at the time in or near Vukovar, as was the UN peace mediator, Cyrus Vance (former US President Carter's Secretary of State). Ironically the siege, despite its brutality, contributed to the beginning of a resolution to the war towards year-end (see below). Allegedly, said the Croat authorities at the time, the Vukovar surrender was an attempt to prevent further devastation of Dubrovnik and other cities.

On 19 December, during the heaviest fighting of the war, the Serbian Autonomous Regions in Krajina and western Slavonia officially declared themselves the Republic of Serbian Krajina. In early November 1991 the Croatian army began a successful counter-attack in Western Slavonia, marking a turning point of the war. Operation Otkos 10, lasting from 31 October until 4 November, resulted in Croatia recapturing 300 km² in area from Bilogora Mountain to Mount Papuk. Further advances were made in the second half of December - Operation Orkan 91 - but at that point a lasting cease-fire was about to be signed (in January 1992). In six months, 10,000 people had died, hundreds of thousands had fled, and tens of thousands of homes had been destroyed.

In late 1991, all the Croatian democratic parties gathered together to form a government of national unity and to confront the Yugoslav Army and Serbian paramilitaries. Ceasefires were frequently signed, mediated by foreign diplomats, but also frequently broken. This was part of the tactics on both sides. The Croatians lost much territory, but profited by being able to expand the Croatian Army - from the seven brigades it had at the time of the first cease-fire to the 64 brigades it had at the time the last one was signed.

Between October 1991 and February 1992, the Croatian government reportedly funded a covert unit under the command of Tomislav Merčep that committed several crimes, involving the killing of prisoners, mostly ethnic Serbs, in a field near Pakrac, in what would later become known as the "Pakračka poljana" case. The killings were initially covered up, but a decade later, five members of this unit, Munib Suljić, Igor Mikola, Siniša Rimac, Miro Bajramović and Branko Šarić, were indicted on several criminal charges related to these events, and later convicted. Tomislav Merčep himself was not indicted in these proceedings.

1992: Ceasefire holds

The final UN-sponsored ceasefire, the twenty-first, was reached in January 1992. From December 1991, after a series of unsuccessful cease-fires, the United Nations deployed a protection force in Serbian-held Croatia. The United Nations Protection Force was deployed to supervise and maintain the agreement. On 7 January 1992, JNA pilot Emir Šišić shot down a European Community helicopter in Croatia, killing five truce observers. Croatia was officially recognised by European community on 15 January 1992. The JNA began to withdraw from Croatia—even Krajina—although Serb paramilitary groups clearly retained the upper hand in the newly occupied territories. The warring parties mostly moved to entrenched positions as The Yugoslav People's Army soon retreated from Croatia into Bosnia and Herzegovina where a new conflict was on the rise. Croatia became a member of the United Nations on 22 May 1992, which was conditional upon Croatia amending its constitution to protect the human rights of minority groups and dissidents.

The Yugoslav People's Army took thousands of prisoners during the war in Croatia, and interned them in camps in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro. The Croatian forces also captured some Serbian prisoners, and the two sides agreed to several prisoner exchanges, which caused most of them to be freed by the end of 1992. Some of the infamous prisons have included the Sremska Mitrovica camp, the Stajićevo camp and the Begejci camp in Serbia and the Morinj camp in Montenegro. The Croatian Association of Prisoners in Serbian Concentration Camps was later founded in order to help the victims of prison abuse. The Croatian Army also established detention camps, like Lora prison camp in Split.

Armed conflict in Croatia continued intermittently at a smaller scale. There were several smaller operations undertaken by Croatian forces, in order to relieve the siege of Dubrovnik, and other Croatian cities (Šibenik, Zadar and Gospić) from the Serb Krajina grip. A partial list includes:

- at the Miljevci plateau (between Krka and Drniš), 21–22 June 1992

- in the Dubrovnik hinterland:

- at the Križ hill near Bibinje and Zadar.

Also, Slavonski Brod (from the mountain of Vučjak) and Županja were often shelled from Serb-held parts of Bosnia. Županja was shelled for more than 1000 days.

1993: Further Croatian military advances

Intermittent armed conflict in Croatia continued in 1993 at a smaller scale than in 1991 and 1992. There were more successful operations by Croatian forces, to recover territory and relieve Croatian cities (e.g. Zadar and Gospić) from Serb shelling attacks, but between the 1992 ceasefire and 1995 Croatian offensives, fighting was limited and total effective military action in those three and a half years was only about two weeks.

In early 1993, there were three notable operations:

- at the hydroelectric Peruća Dam, 27–28 January 1993

- Operation Maslenica, area around Maslenica, near Zadar, 22 January - 10 February 1993

- Operation Medak pocket, area near Gospić, 9–17 September 1993.

While most of these above operations were a relative success for the Croatian government, the successful Operation Medak pocket in 1993 caused sharp reactions of countries and organizations that had anti-Croatian and pro-Serb attitude during the war. This led the Croatian army to undertaking no offensive action during the subsequent 12 months. The ICTY later indicted Croatian officers Janko Bobetko, Rahim Ademi, Mirko Norac and others for the alleged crimes committed during this operation. Norac was later found guilty by the Croatian court.

There were many UN resolutions that required Croatia to retreat to previous positions and that Croatia must restrain from military operations. Some Croat elements felt aggrieved, as no such resolutions had prevented the Serbian forces from attacking Croatia in the earlier stages of the war (when the disturbances were considered national, not international). In October 1993, the United Nations Security Council affirmed for the first time that the United Nations Protected Areas were an integral part of the Republic of Croatia.

During 1992 and 1993, an estimated 225,000 Croats, including refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina and others from Serbia settled in Croatia. A notable number of Bosniaks also fled to Croatia (which was the largest initial destination for Bosniak refugees). Croatian volunteers and some conscripted soldiers participated in the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Some of President Tuđman's closest associates, notably Gojko Šušak and Ivić Pašalić, were from Croat-dominated Herzegovina, and aimed to help the Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina, financially and otherwise.

During the same period, Croatia also accepted 280,000 Bosniak refugees from the Bosnian War. The large number of refugees was significantly straining Croatian economy and infrastructure. The American Ambassador to Croatia, Peter Galbraith, tried to put the amount of Muslim refugees in Croatia into proper perspective in an interview on 8 November 1993. He said the situation would be the equivalent of the USA taking in 30,000,000 refugees.

In Zagreb, a defense official said two long-range "Luna" rockets, each carrying some 1,100 pounds of explosives, hit Lučko, six miles southwest of the city's downtown on September 11.

On 18 February 1993 Croatian authorities signed the Daruvar Agreement with local Serb leaders in Western Slavonia. The Agreement was kept secret and was working towards normalizing life for the locals on the battlefield line. However, the Knin authorities learned of the deal and arrested the Serbian leaders responsible for it. It was widely believed that the Serb leaders there were also willing to accept peaceful reintegration into Croatia.

In 1993, the Croats and Bosniaks started the Croat-Bosniak conflict in Bosnia, just as each was fighting with the Bosnian Serbs. Franjo Tuđman participated in the peace talks between the Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Bosniaks, which resulted in the Washington Agreement of 1994. This led to the dismantling of the statelet of Herzeg-Bosnia and reduced the number of warring factions from three to two.

1994: Erosion of support for Krajina

In March 1994, the Krajina authorities signed a cease-fire. In late 1994, the Croatian Army intervened several times in Bosnia: 1–3 November in the operation "Cincar" near Kupres, and 29 November - 24 December in the "Winter 94" operation near Dinara and Livno. These operations were undertaken in order to detract from the siege of the Bihać region and to approach RSK capital Knin from the north, de facto encircling it on three sides.

During this time, unsuccessful negotiations were under way between Croatian and RSK governments mediated by the UN. The disputes included opening the Serb-occupied part of the Zagreb-Slavonski Brod highway near Okučani to through traffic, as well as the putative status of majority Serbian areas within Croatia. Repeated failures on these two issues would serve as triggers for the two Croatian offensives in 1995.

At the same time, the Krajina army continued the Siege of Bihać together with the Army of Republika Srpska from Bosnia. Michael Williams, a spokesman for the United Nations peacekeeping force, said that the village of Vedro Polje west of Bihać had fallen to a Croatian Serb unit in late November 1994. Mr. Williams added that heavy tank and artillery fire against the town of Velika Kladuša in the north of the Bihać enclave was coming from the Croatian Serbs. Moreover, Western military analysts said that among the impressive array of Serbian surface-to-air missile systems that surround the Bihac pocket on Croatian territory, there is a modernized SAM-2 system whose degree of sophistication suggests that it was probably brought there recently from Belgrade.

A letter dated 3 April 1993 from, inter alia, Milan Martić as Minister of the Interior to the Assembly of the Republika Srpska, written on behalf of “the Serbs from the Republic of Serbian Krajina”, advocated a joinder of the “two Serbian states as the first stage in the establishment of a state of all Serbs”. On 21 January 1994, during the election campaign for the Krajina presidential elections, Martić stated that he would “speed up the process of unification” and “pass on the baton to our all Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević.”

1995: End of the war

In early May 1995, violence again erupted. RSK lost support from the Serbian government in Belgrade, partly in response to international pressure. At the same time, the Croatian army reclaimed all of what was previously occupied territory in western Slavonia during Operation Flash. As a retaliation, Serb forces attacked Zagreb with rockets, killing 7 and wounding over 175 civilians. In August 1995, Croatia started Operation Storm and quickly overran most of the RSK, except for a small strip near the Serbian border. In four days, approximately 150-200,000 Serbs left Croatia.

RSK sources (Kovačević, Sekulić, Vrcelj, documents of HQ of Civilian Protection of RSK, Supreme Council of Defense) have confirmed that evacuation of Serbs was organized and planned beforehand. (citing: see section "Literature") According to Amnesty International (AI), the operation led to the ethnic cleansing of up to 200,000 Croatian Serbs, as well as murder and torture of Serbs, soldiers and civilians, as well as plunder of the Serb civilian property. The BBC noted 200,000 Serb refugees at one point. The ICTY stated that Operation Storm was a legal military campaign intended to help Croatia regain control over its own territory, but still noted that war crimes were done in the process. The indictment against general Ante Gotovina cited at least 150 Serb civilians killed in the aftermath. Croatian Helsinki Committee registered 677 killed Serb civilians in the operation.

The nature of this exodus is still disputed among Serbs and Croats: the former tend to claim the ethnic cleansing was planned by the Croatian government, while the latter pinpoint Tuđman's promise not to attack civilians and attribute the cases of killing of the Serb civilians that remained to revenge by groups and individuals outside of the Croatian Army's control.

A few months later, the war ended with the negotiation of the Dayton Agreement (in Dayton, Ohio). This was later signed in Paris in December 1995.

Timeline of major events

| Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Croatia |

|

| Early history |

| Middle Ages |

| Modernity |

|

20th century

|

| Contemporary Croatia |

| Timeline |

|

|

| Date | Event |

| 17 August 1990 | Log Revolution |

| 1–3 March 1991 | Pakrac clash |

| 31 March 1991 | Plitvice Lakes incident |

| 1 April 1991 | Republic of Serbian Krajina is proclaimed |

| 2 May 1991 | Borovo Selo killings |

| 25 June 1991 | Slovenia and Croatia declare their independence |

| 1 August 1991 | Dalj killings |

| August 1991 | Battle of Dalmatia |

| September 1991 | Battle of Vukovar begins |

| 14–19 September 1991 | Main part of the Battle of the barracks |

| 1 October 1991 | Start of the Siege of Dubrovnik |

| 4 October 1991 | Dalj massacre |

| 5 October 1991 | Croatia commences general mobilization |

| 7 October 1991 | Bombing of Banski dvori |

| 10 October 1991 | Lovas massacre |

| 10–13 October 1991 | Široka Kula massacre |

| 16–18 October 1991 | Gospić massacre |

| 20 October 1991 | Baćin massacre |

| 31 October 1991 – 4 November 1991 | Operation Otkos 10 |

| 7 November 1991 | Ethnic cleansing of Lipovaca, Vukovići and Saborsko |

| 14 November 1991 | Battle of the Dalmatian channels |

| 18 November 1991 | Battle of Vukovar ends, Vukovar massacre |

| 18 November 1991 | Škabrnja massacre |

| 12 December 1991 – 3 January 1992 | Operation Orkan 91 |

| 13 December 1991 | Voćin massacre |

| 21 December 1991 | Bruška massacre |

| 30 May 1992 | UN imposes sanctions against FR Yugoslavia |

| 21 June 1992 | Miljevci plateau battle |

| 22 September 1992 | FR Yugoslavia ousted from the UN |

| 22 January 1993 | Operation Maslenica |

| 9–17 September 1993 | Operation Medak Pocket |

| January 1995 | Creation of Z-4 plan |

| 1–3 May 1995 | Operation Flash |

| 2–3 May 1995 | Zagreb rocket attack |

| 4–7 August 1995 | Operation Storm |

| 12 November 1995 | Signing of Erdut agreement |

Nomenclatorial note

The 1991–1995 war in Croatia is variously called:

- Homeland War – a direct translation of Croatian Domovinski rat

- Patriotic War – a stylistically different translation, reminiscent of the fact that the 1991–95 conflict was as defining for Croatia as 1812 and 1941-45 wars were for Russia and USSR

- War of Independence & War in Croatia – generic terms

- Civil war in Croatia – a direct translation of Serbian and Croatian Građanski rat u Hrvatskoj.

Type of war: Two conflicting views exist as to whether the war was a civil or an international war. Since neither Croatia or Yugoslavia declared war on each other, a prevailing view in Serbia was that it was a civil war between Croats and Serbs in Croatia. By contrast, the prevailing view in Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia is that the war was a war of aggression from Serbia and Montenegro against Croatia, supported by local rebel Serbs.

The ICTY (in its indictments) characterized the war to have been civil war until 8 October 1991. when Croatia declared independence, and international war after that date, since another country, Yugoslavia, held its troops (JNA) there. In the Duško Tadić case, the ICTY stated:

The armed conflict in the former Yugoslavia started shortly after the date on which Slovenia and Croatia declared their independence on 25 June 1991 between the military forces of the SFRY and Slovenia and Croatia. Such armed conflict should of course be characterized as internal because the declarations of independence were suspended in consequence of the proposal of the EC for three months. After the expiration of the three months’ period, on 7 October 1991, Slovenia proclaimed its independence with effect from that date, and Croatia with effect from 8 October 1991. So the armed conflict in the former Yugoslavia should be considered international as from 8 October 1991 because the independence of these two States was definite on that date.

Likewise, two conflicting views exist as to whether parts of Croatia that became part of the self-proclaimed Republic of Srpska Krajina in 1991 were "Serb-occupied territories" as opposed to "Serb-held territories". In its indictment against Milosevic, the ICTY stated the following:

All acts and omissions charged as Grave Breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 occurred during the international armed conflict and partial occupation of Croatia...Displaced persons were not allowed to return to their homes and those few Croats and other non-Serbs who had remained in the Serb-occupied areas were expelled in the following months. The territory of the RSK remained under Serb occupation until large portions of it were retaken by Croatian forces in two operations in 1995. The remaining area of Serb control in Eastern Slavonia was peacefully re-integrated into Croatia in 1998.

See also

- Arbitration Commission of the Peace Conference on the former Yugoslavia

- Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts

- Minefields in Croatia

- Virovitica-Karlovac-Karlobag line

Casualties

Most sources place the total amount of deaths on both sides at around 20,000. Croatian casualties are estimated at around 12,000 to 13,000 killed and missing. According to Colonel Ivan Grujic, 12,000 were killed or went missing including some 6,788 soldiers and 4,508 civilians. Official figures from Croatia from 1996 lists 12,000 killed, 35,000 wounded, 180,000 destroyed apartments, 25% of its economy destroyed, and 27 billion US dollars of material damage. Around 196,000 to 221,000 Croats were displaced during the war. Other sources, like UNHCR, listed some 500,000 Croats and other non-Serbs as refugees after being expelled from Croatian territory overrun by Serb rebels. According to the OSCE in 2006, 221,000 were displaced of which 218,000 had returned. The majority were displaced during the initial fighting and the JNA offensives of 1991 and 1992.

Some 150,000 Croats from Republika Srpska and Serbia have obtained Croatian citizenship since 1991.

The Belgrade based non-government organization Veritas lists 6,780 killed and missing from the Republic of Serbian Krajina including 4,324 combatants and 2,344 civilians. Most of them were killed or missing in 1991 (2,442) and during 1995 (2,394). Most deaths occurred in Northern Dalmatia (1,632). The JNA officially acknowledged 1,279 killed in action during the entire war, although the actual number was probably considerably greater, since casualties were consistently underreported during the war. For example, in the case of one brigade, while official reports spoke of two lightly wounded after an engagement, the actual number was 50 killed and 150 wounded according to the unit's intelligence officer.

According to Serbian sources some 447,316 Serbs were displaced during the war of which 120,000 were displaced in 1991–1993 and 250,000 were displaced after Operation Storm. Most international sources place the number of Serbs displaced at around 300,000. According to Amnesty International 300,000 were displaced from 1991–1995 of which 117,000 are officially registered as having returned as of 2005. According to OSCE 300,000 were displaced during the war of which 120,000 are officially registered as having returned as of 2006. However, it is believed the number does not reflect the de facto number of returnees because many return to Serbia, Montenegro, or Bosnia and Herzegovina after officially registering in Croatia. According to the UNHCR in 2008, 125,000 are registered as having returned to Croatia, of whom 55,000 remain permanently.

Shelled Croatian cities

Many Croatian cities were shelled by RSK forces from rebel Serb-controlled areas, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Serbia.

The most shelled cities were: Vukovar, Slavonski Brod (from the mountain of Vučjak) and Županja (for more than 1000 days.), Vinkovci, Osijek, Nova Gradiška, Šibenik, Sisak, Dubrovnik, Zadar, Gospić, Karlovac, Biograd na moru, Slavonski Šamac. Cities that were also shelled were: Ogulin, Duga Resa, Otočac, Ilok, Beli Manastir, Daruvar, Zagreb,...

References

- ^ "Killed and missing persons from the territories of Republic Croatia and former Republic of Serb Krayina | the Polynational War Memorial". War-memorial.net. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- Meštrović.S (1996), Genocide After Emotion: The Postemotional Balkan War, Taylor & Francis Ltd, p.77. Books.google.se. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- Goldstein, Ivo (1999). Croatia: A History. p. 256. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1850655251.

- ^ Lena Dominelli (2007). Revitalising communities in a globalising world (page 163). Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- ^ Darko Zubrinic. "Croatia within ex-Yugoslavia". Croatianhistory.net. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- Utjecaj srbijanske agresije na stanovništvo Hrvatske, Index.hr, 11-12-2003. Accessdate 2010-10-07.

- ^ "Home again, 10 years after Croatia's Operation Storm". UNHCR. 2005-08-05. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- "IHT". IHT. 2009-03-29. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ http://www.1stweb.cz. "9–15 September 2003 - Transitions Online". Tol.cz. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

{{cite web}}: External link in|author= - ^ "BBC". BBC News. 2003-09-10. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ "Serbia to respond to Croatian genocide charges with countersuit at ICJ". SETimes.com. 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ "UN to hear Croatia genocide claim against Serbia:". tehran times. 2008-11-19. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- "Country Profile: Croatia". Fco.gov.uk. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- "Milan Babić verdict" (PDF). ICTY. 2009-06-26. Retrieved 2010-09-11.He participated in the provision of financial, material, logistical, and political support for the military take-over of territories and requested the assistance or facilitated the participation of Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) in establishing and maintaining control of those territories.

- "Milan Martić verdict" (PDF). ICTY. 2009-06-26. Retrieved 2010-09-11.The Trial Chamber found that the evidence showed that the President of Serbia, Slobodan Milošević, openly supported the preservation of Yugoslavia as a federation of which the SAO Krajina would form a part. However, the evidence established that Slobodan Milošević covertly intended the creation of a Serb state. This state was to be created through the establishment of paramilitary forces and the provocation of incidents in order to create a situation where the JNA could intervene. Initially, the JNA would intervene to separate the parties but subsequently the JNA would intervene to secure the territories envisaged to be part of a future Serb state.

- Template:Sr icon NIN, 23 Dec 1991

(referred in) Template:Hr icon Ivan Strižić: Bitka za Slunj - obrana i oslobađanje grada Slunja i općina Rakovice, Cetingrada, Saborsko i Plitvička Jezera od velikosrbske agresije, Naklada Hrvoje, Zagreb, 2007, p. 124, ISBN 978-953-95750-0-5 - "Milan Martić sentenced to 35 years for crimes against humanity and war crimes". ICTY. 2007-06-12. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- Template:Sr icon Veljko Kadijević: Moje viđenje raspada, Belgrade, 1993., p. 134-135

- The period of Croatia within ex-Yugoslavia

- Greater Serbia: from ideology to aggression, Zagreb, Croatian Information Centre, 1993.

- "Vojislav Seselj indictment" (PDF). The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 2003-01-15. Retrieved 2010-10-08.

- ICTY transcript, case NO. IT-94-1-T.

- ICTY transcript, Milošević's trial.

- ICTY transcript, Milošević's trial, p4.

- Template:Sr icon Fond za humanitarno pravo, Suđenje Miloševiću, Transkripti, 4 December 2002, Svedok C-061.

- "Tuđmana je za posjeta Americi 1987. trebao ubiti srpski vojni likvidator" (in Croatian). Večernji list. 2009-12-09. Retrieved 2010-10-08.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|transtitle=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - "A Country Study: Yugoslavia (Former): Political Innovation and the 1974 Constitution (chapter 4)". The Library of Congress.

- Yugoslav crisis and the world

- By HENRY KAMM, Special to the New York Times (1988-10-09). "Yugoslav Police Fight Off A Siege In Provincial City". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- Reuters (1989-01-12). "Leaders of a Republic In Yugoslavia Resign". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - "IWPR news report: Martic "Provoked" Croatian Conflict". Iwpr.net. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- "Roads Sealed as Yugoslav Unrest Mounts". New York Times. August 19, 1990. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- ^ ICTY (2007-06-12). "The Prosecutor vs. Milan Martic (paragraph 127-150)" (PDF). ICTY. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- Proceedings - Assembly of Western European Union: Actes officiels - Assemblée de l'Union de l'europe occidentale. 1986. p. 107. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- Europa Publication Limited (1999). Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. p. 272. ISBN 1-85743-058-1. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- Kovac, Mirko Deset godina od hrvatske vojne akcije Oluja, Crnogorski književni list, 2005

- "19th anniversary of Plitvice action commemorated". Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Croatia. 2010-03-31. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- John Pike (2005-10-20). "Serbo-Croatian War". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- Stephen Engelberg (12 December 1991). "Germany Raising Hopes of Croatia". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

Before the war, the Yugoslav Army drew its soldiers from conscription in all of the Yugoslav republics. Now it must rely on Serbian reservists and Serb irregulars who are poorly trained. A recent report by the monitoring mission concluded that the army was routinely shelling civilian areas.

- Michael Mann (2005). The dark side of democracy: explaining ethnic cleansing. p. 363. ISBN 0-521-53854-8. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- Final report of the United Nations Commission of Experts

established pursuant to security council resolution 780 (1992) (1994-12-28). "The military structure, strategy and tactics of the warring factions". Retrieved 2010-09-11.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|author=at position 57 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Final report of the United Nations Commission of Experts, established pursuant to security council resolution 780 (1992), Annex VIII - Prison camps; Under the Direction of: M. Cherif Bassiouni; S/1994/674/Add.2 (Vol. IV), 27 May 1994, Special Forces, (p. 1070). Accessdate 20 October 2010.

- Blaskovich, Jerry (1997). Anatomy Of Deceit, Realities Of War In Croatia, New York: Dunhill Publishing. ISBN 0-935016-24-4.

- William Safire (14 March 1993). "ON LANGUAGE; Ethnic Cleansing". New York Times. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- Martin Špegelj: "Memories of a Soldier" ("Uspomene Vojnika"), Zagreb 2nd edition

- Joseph Pearson, 'Dubrovnik’s Artistic Patrimony, and its Role in War Reporting (1991)' in European History Quarterly, Vol. 40, No. 2, 197-216 (2010).

- "UN court increases Serb officer's sentence for Vukovar massacre". France24. 2009-05-05. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- "Hague triples Vukovar jail term". BBC News. 5 May 2009. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- "U.N. tribunal to rule in Vukovar massacre case". Reuters. 2007-09-25. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- The End of Greater Serbia

- Obituary: Slobodan Milosevic

- Decision of the ICTY Appeals Chamber; 18 April 2002; Reasons for the Decision on Prosecution Interlocutory Appeal from Refusal to Order Joinder; Paragraph 8

- "Balkans: Vukovar Massacre Trial Begins In The Hague". Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. 2005-10-11. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- "Dossier: Pakračka Poljana". Yupress.com excerpts from Feral Tribune. May 19, 1995.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - Davor Butković (2005-09-17). "Pobjeda pravde". Jutarnji list (in Croatian). Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- "Vrhovni Sud Republike Hrvatske-Presuda i rješenje broj: I Kž 81/06-7" (in Croatian). Supreme Court of the Republic of Croatia. 2006-05-10. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- Paul L. Montgomery (1992-01-10). "Talks on Yugoslavia Resume With New Cooperative Tone". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- "MLADEN MARKA ’S PRE-TRIAL BRIEF PURSUANT TO RULE 65 ter (F)", United Nations, Criminal Tribunal, April 2007, PDF file: UN-PTB-PDF.

- HIC Hrvatski spomenar - 21. kolovoza-31. kolovoza

"Srbi s planine Vučjak u BiH neprekidno granatiraju Slavonski Brod" - ^ HIC 26. listopada

"Neprekinuta opća opasnost u Županji traje još od travnja 1992.......Srbi iz Bosne grad gađaju oko 12 ili oko 15 sati, kada je na ulicama najviše ljudi." - ^ Hrvatsko kulturno vijeće Zdravko Tomac: Strah od istine, Jan 15, 2010, accessed Feb 7, 2010

- ^ (Croatian) War in Croatia 1991-95, Part II.

- "CT/MO/1015e - RAHIM ADEMI AND MIRKO NORAC CASE TRANSFERRED TO CROATIA". pub. The Hague, 1 November 2005. Archived from the original on 2008-03-17. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

Today, 1 November 2005, the Rahim Ademi and Mirko Norac case was officially transferred to the Republic of Croatia by the ICTY. This is the first case in which persons already indicted by the Tribunal have been referred to Croatia. It is the only case, out of 10, that the Tribunal's Prosecution has requested be transferred to Croatia.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Croatia jails war crimes general". BBC News. 11:52 GMT, Friday, 30 May 2008 12:52 UK. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

He was sentenced to seven years in prison for failing to stop his soldiers killing and torturing Serbs in 1993. ... The charge sheet included the killing of 28 civilians and five prisoners. Some of the victims were tortured before they were killed.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "UN Security Council resolution 871 (1993) on the situation in Former Yugoslavia". 1993-10-03. Retrieved 2010-09-11.7. Stresses the importance it attaches, as a first step towards the implementation of the United Nations peace-keeping plan for the Republic of Croatia, to the process of restoration of the authority of the Republic of Croatia in the pink zones, and in this context calls for the revival of the Joint Commission established under the chairmanship of UNPROFOR; 8. Urges all the parties and others concerned to cooperate with UNPROFOR in reaching and implementing an agreement on confidence-building measures including the restoration of electricity, water and communications in all regions of the Republic of Croatia, and stresses in this context the importance it attaches to the opening of the railroad between Zagreb and Split, the highway between Zagreb and Zupanja, and the Adriatic oil pipeline, securing the uninterrupted traffic across the Maslenica strait, and restoring the supply of electricity and water to all regions of the Republic of Croatia including the United Nations Protected Areas

- Jerry Blaskovich, Anatomy of Deceit: An American Physician's First-hand Encounter With The Realities Of The War In Croatia

- "Croatia Fighting Worsens as Zagreb Suburb Is Hit". New York Times. 1993-09-11. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- "Bosnia and Herzegovina - Background". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 2010-09-11.Bosnia and Herzegovina's declaration of sovereignty in October 1991 was followed by a declaration of independence from the former Yugoslavia on 3 March 1992 after a referendum boycotted by ethnic Serbs. The Bosnian Serbs - supported by neighboring Serbia and Montenegro - responded with armed resistance aimed at partitioning the republic along ethnic lines and joining Serb-held areas to form a "Greater Serbia." In March 1994, Bosniaks and Croats reduced the number of warring factions from three to two by signing an agreement creating a joint Bosniak/Croat Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Roger Cohen (1994-12-02). "CONFLICT IN THE BALKANS: IN CROATIA; Balkan War May Spread Into Croatia". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- Roger Cohen (1994-10-28). "Hard-Fought Ground". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- "The Prosecutor vs. Milan Martic (paragraph 335-336)" (PDF). ICTY. 2007-06-12. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

Efforts to unify the Croatian Krajina and the Bosnian Krajina continued throughout 1992 until 1995. The evidence shows that the RSK leadership sought an alliance, and eventually unification, with the RS in BiH and that Milan Martić was in favour of such unification. A letter dated 3 April 1993 from, inter alia, Milan Martic as Minister of the Interior to the Assembly of the RS, written on behalf of "the Serbs from the RSK", advocates a joinder of the "two Serbian states as the first stage in the establishment of a state of all Serbs". Moreover, in this regard, the Trial Chamber recalls the evidence concerning operation Koridor 92. On 21 January 1994, during the election campaign for the RSK presidential elections, Milan Martić stated that he would "speed up the process of unification" and "pass on the baton to our all Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic."

- Barić, Nikica: Srpska pobuna u Hrvatskoj 1990.-1995., Golden marketing. Tehnička knjiga, Zagreb, 2005

- Drago Kovačević, "Kavez - Krajina u dogovorenom ratu", Beograd 2003., p. 93.-94

- Milisav Sekulić, "Knin je pao u Beogradu", Bad Vilbel 2001., p. 171.-246., p. 179

- Marko Vrcelj, "Rat za Srpsku Krajinu 1991-95", Beograd 2002., p. 212.-222.

- 13 mei 2007. "RSK Evacuation Practise one month before Operation Storm". Nl.youtube.com. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Croatia: "Operation Storm" - still no justice ten years on by Amnesty International, 26 August 2005.

- "Evicted Serbs remember Storm", Matt Prodger, BBC News

- "Croatia marks Storm anniversary", BBC News, 5 August 2005.

- "Croatian general accused of ethnic cleansing against Serbs goes on trial". The Independent. 12 March 2008. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- Marina Karlović-Sabolić (2001-09-15). "Prohujalo s Olujom". Slobodna Dalmacija. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- Kinzer, Stephen SANCTIONS DRIVING YUGOSLAV ECONOMY INTO DEEP DECLINE The New York Times, 31 August 1992. Accessdate 12 August 2010.

- Sudetic, Chuck U.N. Expulsion of Yugoslavia Breeds Defiance and Finger-Pointing The New York Times, 24 September 1992. Accessdate 12 August 2010.

- "PROSECUTOR v. DUSKO TADIC a/k/a "DULE"". ICTY. 1995-10-05. Retrieved 2010-09-09.(C. Characterization of the Conflict in the Former Yugoslavia, paragraph 17)

- ICTY (2002-10-22). "Milošević Indictment (IT-02-54) - paragraph 86, 109" (PDF). ICTY. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|sprache=(help) - Civil and Political Rights in Croatia. Human Rights Watch (October 1995). Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ Croatia: Selected Developments in Transitional Justice. International Center for Transitional Justice. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- Meštrović.S (1996), Genocide After Emotion: The Postemotional Balkan War, Taylor & Francis Ltd, p.77-78. Books.google.se. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- Bilten. Veritas (December 1999). Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- Croatia: Operation "Storm" - Still No Justice Ten Years On. Amnesty International (4 August 2005). Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- Croatia. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- HIC Hrvatski spomenar - 21. kolovoza-31. kolovoza

"Srbi s planine Vučjak u BiH neprekidno granatiraju Slavonski Brod"

Literature

- Barić, Nikica: Srpska pobuna u Hrvatskoj 1990-1995., Golden marketing. Tehnička knjiga, Zagreb, 2005. (from this book are references under, until Vrcelj)

- RSK, Vrhovni savjet odbrane, Knin, 4. avgust 1995., 16.45 časova, Broj 2-3113-1/95. Faksimil ovog dokumenta objavljen je u/The faximile of this document was published in: Rade Bulat "Srbi nepoželjni u Hrvatskoj", Naš glas (Zagreb), br. 8.-9., septembar 1995., p. 90.-96. (faksimil je objavljen na stranici 93./the faximile is on the page 93.).

- Vrhovni savjet odbrane RSK (The Supreme Council of Defense of Republic of Serb Krajina) brought a decision 4 August 1995 in 16.45. This decision was signed by Milan Martić and later verified in Glavni štab SVK (Headquarters of Republic of Serb Krajina Army) in 17.20.

- RSK, Republički štab Civilne zaštite, Broj: Pov. 01-82/95., Knin, 02.08.1995., HDA, Dokumentacija RSK, kut. 265

- RSK, Republički štab Civilne zaštite, Broj: Pov. 01-83/95., Knin, 02.08.1995., Pripreme za evakuaciju materijalnih, kulturnih i drugih dobara (The preparations for the evacuation of material, cultural and other goods), HDA, Dokumentacija RSK, kut. 265

- Drago Kovačević, "Kavez - Krajina u dogovorenom ratu", Beograd 2003., p. 93-94.

- (Note: Drago Kovačević was during the existence of so-called RSK the minister of informing and the mayor of Knin, the capitol of self-proclaimed state)

- Milisav Sekulić, "Knin je pao u Beogradu", Bad Vilbel 2001., p. 171-246., p. 179.

- (Note: Milisav Sekulić was a high military officer of "Srpska vojska Krajine" (Republic of Serb Krajina Army). Book review with excerpts

- Marko Vrcelj, "Rat za Srpsku Krajinu 1991-95", Beograd 2002., p. 212-222.

- Silber, Laura and Little, Allan (1997). Yugoslavia : Death of a Nation. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-026263-6. Accompanies the BBC series of the same title.

- Zimmermann, Warren, ed. (1999). War in the Balkans: A Foreign Affairs Reader, Council on Foreign Relations Press (June). ISBN 0-87609-260-1.

Media

- Harrison's Flowers (2000), directed by Elie Chouraqui. When a Newsweek photojournalist disappears in war-torn Vukovar, his wife travels to find him.

- The Death of Yugoslavia (1995). A BBC series with extensive interviews of prominent Croat and Serb protagonists.

- Truth (director unknown). A Serbian-produced documentary with a brief history of the war from a Serb point of view, while examining in detail atrocities committed against Serbs.

- Hrvatska Ljubavi Moja Jakov Sedlar, movie by Jakov Sedlar showing accounts by Jews and American officials about the Oluja and the war as a whole.

- ER. The character of Dr. Luka Kovač, played by Goran Višnjić, who first appeared on the series in 1999 and is still a main character as of 2007, lost his wife and children in the war. They were killed when a grenade shell hit their house.

External links

- International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia , World Courts and Sense

- Dr. R. Craig Nation. "War in the Balkans 1991-2002." Strategic Studies Institute, 2002, ISBN 1-58487-134-2

- Article on globalsecurity.org

- Article on onwar.com

- Croatia Between Aggression and Peace

- Template:Hr icon Resources about the war on hic.hr

- Template:Hr icon Another resource from hic.hr

- Ivo Skoric - A Story About the War in Croatia

- Operation Storm Destroyed "Greater Serbia", Balkan Insight 20 January 2006

- Vijesti_net - "Rat za mir" About movie that deals with Montenegrin aggression on Dubrovnik area

- Template:Sr icon NIN Zloupotreba psihijatrije (Abuse of psychiatry)

| Yugoslav Wars | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wars and conflicts |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Background | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anti-war protests | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor states | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unrecognized entities |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| United Nations protectorate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Armies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military formations and volunteers |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External factors | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Politicians |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Top military commanders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other notable commanders |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Key foreign figures | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||